Warrior (comics)

| Warrior | |

|---|---|

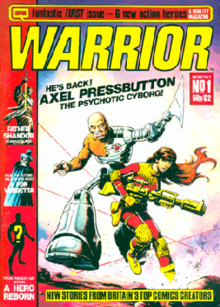

Warrior #1 (March 1982), featuring an image of Axel Pressbutton by Steve Dillon. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Quality Communications |

| Schedule | Monthly |

| Format | Ongoing series |

| Genre | |

| Publication date | March 1982 – January 1985 |

| No. of issues | 26 |

| Creative team | |

| Created by | Dez Skinn |

| Written by | Alan Moore Steve Parkhouse Steve Moore[Note 1] Paul Neary |

| Artist(s) | Garry Leach David Lloyd Steve Dillon John Bolton Paul Neary Mick Austin |

| Editor(s) | Dez Skinn |

Warrior was a British comics anthology that ran for 26 issues between March 1982 and January 1985. It was edited by Dez Skinn and published by his company Quality Communications. It featured early work by numerous figures who would go on to successful careers in the industry, including Alan Moore, Alan Davis, David Lloyd, Steve Dillon, and Grant Morrison; it also included contributions by the likes of Brian Bolland and John Bolton, while many of the magazine's painted covers were by Mick Austin.

Publication history

[edit]Creation

[edit]The title Warrior was recycled from a short-lived fanzine Skinn had once edited/published; in 1974-1975, he had produced six issues of Warrior: Heroic Tales Of Swords and Sorcery. The fanzine featured reprints and new strips, art, and writing from such creators as Steve Parkhouse, Dave Gibbons (who designed the logo), Michael Moorcock, Frank Bellamy, Don Lawrence, and Barry Windsor-Smith.[1]

Following the success of House of Hammer and Starburst, Skinn was head-hunted by Stan Lee of Marvel Comics to take over the company's ailing British division.[2] There, his work included creating the well-received anthology Hulk Comic, which mixed reprints of extant American material and work sourced from the burgeoning British comics scene, much of it drawn from Skinn's contacts in both the industry and fanzines. In 1980, Skinn left Marvel UK[3] – later explaining that he felt the demands on the wing's output had reduced it from making "quality material" to "quantity material".[4] In response he set up Quality Communications, planning to follow the same successful template with a creator-owned ethos.[5] He revived the name of the 70s fanzine for the project:

"Warrior seemed an obvious choice nobody else had picked up on — both times! It fit perfectly as a newsstand logo".[6]

The contents of Warrior deliberately mimicked the successful elements from his work for other publishers - Marvelman was planned to emulate the revival of Captain Britain in the Hulk Weekly's Black Knight strip, V for Vendetta traded on similar motifs to Night Raven, Axel Pressbutton had a similar theme to Abslom Daak from Doctor Who Monthly and Father Shandor fitted the sword-and-sorcery profile of Conan the Barbarian.[5] Skinn recruited many of the writers and artists he had previously worked with at Marvel, including Steve Moore, Gibbons, Steve Dillon, Steve Parkhouse and David Lloyd, adding established creators like Bolland and Bolton, as well as emerging young talent such as Alan Moore and Garry Leach. Leach would subsequently be assigned as the magazine's art director.[7][5]

Part of the attraction for the creative staff was Warrior's unusual payment model. While page rates for the initial work were lower than those offered by rivals IPC Magazines, DC Thomson and Marvel UK, the creators of each strip would receive a share in their output's ownership and increased royalties for reprints, instead of the normal industry practice of work-for-hire. Skinn hoped to follow the example of the French anthology Métal hurlant, with the various strips both syndicated overseas and, as each reached enough material, in collected albums.[5]

Contents

[edit]The 52-page magazine had colour front and back covers (the latter usually carrying advertising, but occasionally containing a 'clean' version of the front cover) but was otherwise in black-and-white; initially it was priced at 50p. The first issue was dated March 1982, with Skinn's editorial noting work had begun in April 1981, but the creators had been encouraged to work at getting the first issue "right" rather than working towards a deadline.[8] The issue included a two-page article introducing the creators behind the magazine.[9] Both the editorial-cum-contents page and Skinn's replies to readers' letters would adopt a similarly candid approach, giving a generally unvarnished look at the magazine's frequent production problems. Letters page 'Dispatches' would print both positive and negative missives, with the latter often being upbraided by Skinn or other members of the creative team.[10][11][12]

A Summer Special was planned in 1982 to be a separate special edition alongside the regular issues, featuring self-contained stories.[13] However, various production issues saw some of the planned material merged into various regular issues of Warrior instead;[14] in 2007, Skinn would attribute this to himself getting excited and overextending. Repurposed material included the cover for #4 – which bore the text 'Summer Special' instead of a date. As a result, both Big Ben[15] and Raiko from Demon at the Gates of Dawn were featured in the illustration but not in the magazine's content, causing some confusion to readers.[14] The Summer Special also bequeathed The Golden Amazon, the V for Vendetta strip "Vertigo" and the two-page Madman strip "ChronoCycle Mk.1" to Warrior #5. The magazine would fluctuate between monthly and bi-monthly, which Skinn would state was in response to the industry slowing down in the winter.[16]

In late 1983, the magazine had a print run of around 30,000 copies.[17] Warrior #15 saw the first of the 'Sweatshop Talk' articles featuring interviews with creators – beginning with Steve Moore being 'interviewed' by his pseudonym Pedro Henry; the pair being one and the same was something of an open secret at the time.[18] Later issues saw 'Henry' interview Skinn,[19] Alan Moore,[20] Leach[21] and Austin.[22]

Warrior universe and Challenger Force

[edit]Skinn wanted the material in Warrior to share a fictional universe, with connections between the strips to be gradually developed, with the various heroes eventually forming a Justice League-style super-team tentatively called Challenger Force. Marvelman, Warpsmith/Aza Chorn, Big Ben and a new character called Firedrake were among the mooted members.[5] As part of the plans for the book, Alan Moore and Steve Moore sketched a far-reaching chronology tying together some of the events from Marvelman, V for Vendetta, Warpsmith and Axel Pressbutton. Due to being potentially irreconcilable due to their relatively close time periods, V for Vendetta was designated as taking place in an alternate universe where Marvelman had never returned;[23] Skinn would joke that V was killed by Kid Marvelman early in his life in the 'regular' universe.[5] Fate, the computer from V for Vendetta, was posited as an invention of Marvelman Family creator Emil Gargunza.[23] The Marvelman strip "The Yesterday Gambit" was set three years in the universe's future, featuring the title character teaming up with 'Warpsmith' to battle Kid Marvelman, with a call-out for the mysterious Firedrake and "the others". Otherwise few of these connections reached print before the title was cancelled, and neither the completed V for Vendetta nor the ongoing Miracleman showed any sign of being connected. However Moore did incorporate the Warpsmiths in Miracleman, making several references to "The Yesterday Gambit". A draft of the timeline was printed in George Khoury's Kimota! The Miracleman Companion in 2001.[23]

A second attempt at more strongly connected series of strips was planned in 1985, with strips Big Ben, The Liberators, The Project Files and Wardroid planned to all be connected to a mysterious foundation called The Project.[24] However, only Big Ben and The Liberators would reach publication before the magazine's cancellation.

Creative and legal problems

[edit]The high level of creator control led to problems; issues began to turn up late when contributors missed deadlines and fill-in artists could not be commissioned, as the originating artists owned the properties.[5] Laser Eraser and Pressbutton stalled when Skinn lost contact with Dillon; material intended for Warrior #16 was replaced by a reprint of one of Pressbutton's appearances from Sounds, and then a one-off war strip by Parkhouse and John Ridgway. Tensions were also growing among the creative staff, with those behind the magazine's more popular features feeling the division of spoils was unfair as they were carrying the less popular features. This was exacerbated by the general lack of spoils themselves; despite acclaim Warrior was losing money, being propped up by the takings of Skinn's Quality Comics store.[5][25] Deadlines were also a problem, as the difficulty in using fill-in artists meant one strip being late could knock a whole issue off schedule.[16] Further problems arose when creative staff began receiving offers from American publishers and had less time to contribute to Warrior, slowing or curtailing storylines.

Marvelman became something of a nexus in the problems surrounding the title. Firstly Alan Moore and artist Alan Davis fell out over an unrelated matter, involving their parallel work on Marvel's Captain Britain, and refused to allow anyone else to continue the story - vetoing a mooted continuation by Grant Morrison.[5] Secondly, Alan Moore's relationship with Skinn deteriorated; a key point of the dispute was a growing suspicion that the editor had not correctly licensed the character in contrary to what he had told the writer. Thirdly, the publishing of a one-off Marvelman Special in July 1984 had drawn legal action for trademark infringement from Marvel Comics; while the strip had already stalled this made potential syndication partners wary as Skinn was attempting to find a package deal for entirety of Warrior's contents.[5] From Warrior #25, the magazine briefly expanded when fellow Quality magazine Halls of Horror was merged into the title.[26]

Publicly, Skinn railed against Marvel and their legal tactics, even going as far as printing his correspondence with the rival publisher's British legal representatives in columns in Warrior while implying that the action was preventing the continuation of Marvelman. However, before the matter could go to court or the creative impasse could be resolved Warrior's losses finally became too much for Skinn. After 26 issues he shuttered the title, and would later estimate that its run had cost him between $36-40,000 in losses. He would later state the loss of Marvelman played no role in the cancellation.[5] As well as the planned 'Project' stories, other victims of the cancellation included Leach superhero strip Power, Steve Moore and Jim Baikie's Claustrophobia and Grysdyke Dean, which was a submission by readers Paul Alexander and Mike Nicholson.[24]

Instead Skinn focused on attempting to sell the reprint rights for the lucrative American market. After some unsuccessful negotiations, Alan Moore and David Lloyd broke ranks to make their own deal with DC Comics, while Skinn and Mike Friedrich of Star*Reach brokered a deal with Pacific Comics for the remainder. Before anything could be published the Pacific folded and its assets were purchased by Eclipse Comics.[5] Eclipse would publish series based on Marvelman (renamed Miracleman) and Pressbutton but would go bankrupt themselves in 1994. Warrior Marvelman and Warpsmith material has since been reprinted in updated form in Marvel's 2014 Miracleman series.[27]

Stories

[edit]V for Vendetta

[edit]Created by Alan Moore and David Lloyd. A masked vigilante battles a fascist British government in an alternate 1997. Episodes of the serial appeared in all but one issue of Warrior, only missing #17.[16] Following the demise of Warrior, the story was picked up by DC Comics, who eventually published the material and its continuation in a ten-issue 1988 limited series.

Marvelman

[edit]A revival of the Mick Anglo-created Golden Age British superheroes Marvelman, Young Marvelman and Kid Marvelman. The strip was written by Alan Moore and initially drawn by Garry Leach before he handed over to Alan Davis. Marvelman featured in #1-11, #15-16, #18 and #20-21; related flashback strips drawn by John Ridgway appeared in #12 (Young Marvelman) and #17 (Marvelman Family). The story was later renamed Miracleman in 1985 when it was published by Eclipse Comics, and would continue until 1993 when the American company folded. Following a long hiatus while copyright issues were resolved it returned to publication under the auspices of Marvel Comics in 2014.

Laser Eraser and Pressbutton

[edit]Sociopathic cyborg assassin Axel Pressbutton had been created by Steve Moore and Alan Moore (under the pseudonyms Pedro Henry and Curt Vile, respectively) for music magazine Dark Star in 1979, and subsequently appeared in the more-widely read Sounds from 1980. For the character's appearances in Warrior, Skinn requested the creation of a female co-star and Axel was joined by the Laser Eraser Mysta Mystralis. The strip appeared in Warrior #1-12 and #15-16 with 'Henry' writing and Steve Dillon drawing most of it; David Jackson and Mick Austin would also provide art for some episodes. However, after a reprint of a Sounds strip in #17, Skinn's editorial claimed the artist had "disappeared" with the artwork for the title. The story would return in #21 and appear again in #24-25, now drawn by Alan Davis.[16] The Warrior strips would be reprinted by Eclipse in the limited series Axel Pressbutton in 1984,[28] after which the American publisher would run new material, first in Laser Eraser and Pressbutton[29] and then as a backup feature in Miracleman.

Father Shandor... Demon Stalker

[edit]The adventures of a medieval Transylvanian monk turned demon hunter. The character had actually debuted in the 1966 Hammer horror film Dracula: Prince of Darkness, played by Andrew Keir (the film's credits referred to the character as 'Sandor'). The comic version had been created by Steve Moore for House of Hammer and was continued in Warrior; issues #1–3 reprinted material from House of Hammer #8, #16, and #21; the rest were original to Warrior. While the initial reprints featured artwork by Bolton the new material was drawn by Jackson. It was one of the most consistent features of the magazine with either Father Shandor or spin-off Jaramsheela (featuring a demonic succubus enemy of the priest) appearing in #1-10, #13-19, #21 and #23-25.[16]

The Spiral Path

[edit]A fantasy sword and sorcery strip by Steve Parkhouse and Bolton,[citation needed] concerning the travails of Caed and his friend's daughter Bethbara in the land of Tairngir. It appeared in #1-2 & #4-12[16] but Warrior ended before a second arc could begin. The completed material was later repackaged as a two-issue 'micro-series' by Eclipse Comics, which was nominated for 'Best Limited Series' at the 1986 Kirby Awards.[30] The story teased a possible continuation, with the title given as The Silver Circle, but this never materialized.

The Legend of Prester John

[edit]A retelling of the story of the legendary Christian king (and not to be confused with the Marvel Comics character of the same name) by Steve Parkhouse and John Bolton. While the strip appeared in Warrior #1 it then disappeared until #11, due to what Skinn's editorial called a "catalogue of ill-luck"; the story was now drawn by John Stokes. However, after #12 it would again disappear for good.[16]

The Madman

[edit]Created, written and initially drawn by Paul Neary. The story concerned the mental journey of Martin Schiller, a catatonic mental patient. The strip debuted in Warrior #2 and ran in #3-5 & #7.[16] As Neary's workload at Marvel UK increased Austin took over art duties from #5.[14] After the planned conclusion failed to arrive for publication in Warrior #8 it was simply abandoned - Skinn would later say Neary "went off the radar in the West Country".[16]

Zirk

[edit]The magazine's ersatz mascot, sweaty, amorous blob Zirk was spun off from Laser Eraser and Pressbutton. The Sultan of Slime received his own solo strip in Warrior #3, written by Steve Moore (under his Pedro Henry pseudonym) and drawn by Brian Bolland. Another appeared in #13, with art from Leach.[16]

Warpsmith

[edit]A science fiction story written by Alan Moore and drawn by Garry Leach concerning the Warpsmiths, a highly advanced race of aliens with the ability to teleport instantaneously. They are locked in a cold war with the Qys Imperium. The characters featured strongly in the mooted chronology of the magazine, first posing as allies of Earth before gradually colonising the world.[23] However, after one - later revealed to be Aza Chorn, but initially only named Warpsmith - appeared as a guest character in "The Yesterday Gambit", only two episodes (in Warrior #9-10),[31] of their own story would be published before Warrior was cancelled. These would subsequently be reprinted as back-up material in Eclipse's Axel Pressbutton series before the characters themselves were folded into Miracleman from 1987. Another story, "Ghostdance", was scripted but did not reach publication before Warrior folded in 1985.[7][32] "Cold War, Cold Warrior" was subsequently coloured by Leach and reprinted by Eclipse in the second issue of their Axel Pressbutton series.

Marvel Comics reprinted Miracleman from 2014 onwards, including the Warpsmith strips.[27] As of 2024[update] the Warpsmiths still feature in the continuing Miracleman storyline, now written by Neil Gaiman.

The Bojeffries Saga

[edit]An absurdist black comedy by Alan Moore and Steve Parkhouse about the eccentric, monstrous Bojefferies family from Northampton (Moore's home town) and their bizarre antics. Only four episodes ran in Warrior (in #12-13 & #19-20).[16] The series was later continued in the anthologies Dalgoda and A1.

The Twilight World

[edit]Set on a dystopian future Earth, where the little life remaining on the planet is threatened by Castle Core, the planet's faulty defence system. Jay Verlane and the alien Fylar set out to destroy it. Written by Steve Moore and drawn by Jim Baikie, the story ran in #14-17.[16] It was later reprinted in colour as back-up material in Eclipse's Laser Eraser and Pressbutton.

Ektryn

[edit]Science fiction fantasy set on the planet Naglfar, by Steve Moore and Cam Kennedy. The strip bore one of the few explicit shared connections in the magazine - Mysta Mystralis was cloned from cell tissue of the title character, effectively making Ektryn a Laser Eraser and Pressbutton prequel. The strip appeared in Warrior #14 and #25.[16]

Bogey

[edit]Future-set private eye story written by Antonio Segura and drawn by Leopoldo Sánchez, imported from Spain and translated into English for Warrior by Skinn, appearing in #22-23 & #26.[16] Not to be confused with Antonio Ghura's 1975 British underground comix volume Bogey.

Big Ben

[edit]Originally created by Dez Skinn and artist Ian Gibson[15] as a possible addition to House of Hammer, the existence of a completed unpublished story with the character led to the editor requesting Big Ben be included in Marvelman. This allowed the strip to be printed in the Marvelman Special (where Skinn was credited as Edgar Henry). Rich Johnston has speculated that Marvel UK's The Thing is Big Ben, starring Ben Grimm of Fantastic Four fame, was intended to prevent Skinn using Big Ben as a title character.[15] Later, new material featuring the character was created for Warrior by Skinn (now credited under his real name); Leach was initially announced as artist[33] but instead Will Simpson would draw the strip. This posited that - contrary to the depiction in Marvelman and later minor appearances in Miracleman - Big Ben was a shape-shifting alien that had taken on the guise of Lord Benjamin Charterhouse Fortescue. As Big Ben, Fortescue fought crime from a headquarters in the Westminster clock tower, which he accessed via a secret lift in the House of Lords, with the assistance of valet Fosdyke and assistant Tanya. These strips appeared in Warrior #19-26;[16] another completed before the cancellation was later included in the "Spring Special" edition of Comics International, and has been subsequently used in Marvel Comics' revival of Miracleman. [15]

The Liberators

[edit]A group of rebels fights the alien Metamorphs in the post-apocalyptic London of 2470; the strip was one of the few to feature clear connections to others in the magazine, with concepts related to Big Ben. The first story was printed in Warrior #22, written by Skinn and drawn by Ridgway.[16] The first of a two-part prequel written by Grant Morrison (some of his earliest professional work) then appeared in #26; due to Warrior's cancellation the second instalment wouldn't be printed until the 1996 'Spring Special'.

The Many World of Cyril Tomkins - Chartered Accountant

[edit]Whimsical comedy story, in which the title character escapes his mundane everyday life by indulging in fantasy. Written by Carlos Trillo with art by Horacio Altuna, the story was another imported from Spain, and appeared in Warrior #25-26.[16]

One-off strips

[edit]- A True Story?: a Tharg's Future Shocks-style piece from the first issue, written by Steve Moore and drawn by Bolland.[16]

- The Golden Amazon: a partial adaptation of John Russell Fearn's pulp science fiction series Golden Amazon by Lloyd, printed in #5.[16] The editorial asked readers to write in if they wanted to see it, though in fact Lloyd's schedule would prevent any follow-up.[11]

- Stir Crazy: an EC Comics pastiche by underground comix artist Hunt Emerson, printed in Warrior #8 after the final episode of The Madman failed to appear.[16]

- The Shroud: a short science fiction strip by Parkhouse and Ridgway printed in #13.[16]

- Home is the Sailor: a World War II story from Parkhouse and Ridgway, printed in #17 in lieu of the planned Laser Eraser and Pressbutton continuation.[16]

- Demon at the Gates of Dawn: originally created by Parkhouse in 1977, this tale of demon-battling samurai Raiko and Tsannu in feudal Japan was announced as the first in an occasional series; Bryan Talbot was announced as artist but no further instalments appeared before the magazine ended.[16]

- Zee-Zee's Terror Zone: an edited reprint of a House of Hammer strip by Martin Asbury, intended as the first of an anthology-style series of unconnected strips. A second in #21 saw Leach and John Boix adapt a Enrique Sánchez Abulí story. [16]

- The Judgement: a previously-unpublished Alan Booth/David Jackson strip created for the 1970s incarnation of Warrior, printed in #20.[16]

- The Black Currant: A comic fantasy strip by Carl Critchlow based in the cartoonist's Thrud the Barbarian universe that featured in Warrior #25.[16]

Reception

[edit]Awards

[edit]Warrior was a critical rather than commercial hit.[5] It obtained considerable success at the Eagle Awards; in 1984 it won 'Favourite Comic (UK)' and 'Favourite Comic Cover (UK)' for Mick Austen's work on Warrior #7, while Marvelman, its lead characters and writer Alan Moore were also honoured.[34] The following year it retained the 'Favourite Comic (UK)' award.[35]

Influence

[edit]As well as syndication rights, Skinn and Friedrich also arranged for unsold issues of Warrior to be shipped and sold in America;[36] in Warrior #5's 'Dispatches' Skinn claimed the US market accounted for 25% of the magazine's sales.[37] While large-format black-and-white magazines were falling out of fashion and the exported Warrior issues only reached speciality stores it drew some influential readers. Skinn would later attribute Alan Moore's selection as writer for Saga of the Swamp Thing - a key factor in the so-called British Invasion - to Dick Giordano and Len Wein being Warrior readers.[16]

Letters page 'Dispatches' meanwhile would attract letters from established industry figures including then-2000 AD editor Steve MacManus[37] Martin Lock[38] Bill Black[39] and Marv Wolfman,[40] as well as future comics figures Kevin O'Neill,[41] Bambos Georgiou,[41][38][42][17] Warren Ellis,[43][33] Lew Stringer,[37] Roger Broughton,[44] Rik Levins[11] and Richard Starkings.[12]

Legacy

[edit]Lew Stringer acclaimed Warrior, stating that Warrior as a whole showed that British comics didn't have to always pander to kids or be restricted to the old ways of storytelling".[45] Comicon.com note the magazine was "incredible, it set the mold for so much of what would come later, and it's a slightly lost portion of UK comics".[46]

Musing on Warrior in a 2017 interview, Skinn surmised: "So did the experiment work? Not for the publisher, no. At least not financially. But it did provide a brilliant showcase for creators not shackled by tradition".[47]

Continuations and revivals

[edit]After Quality Communications took over Fleetway's overseas licence from Eagle Comics, Skinn announced a new 48-page colour version of Warrior for 1986.[48][30] However, the title would not be released.

Alan Moore went on to complete both V for Vendetta and his planned storyline for Marvelman (as Miracleman) working for American publishers. Both have received considerable commercial and critical acclaim; V for Vendetta was adapted for cinema in 2005 and David Lloyd's art inspired the hacktivist group Anonymous, while Miracleman has been continued by Neil Gaiman. Laser Eraser and Pressbutton and The Spiral Path were also exported via Eclipse Comics.

Several Warrior characters were revived for the 1989 anthology A1, published by Leach's Atomeka Press. This included "Ghostdance", a previously-unfinished Alan Moore-written Warpsmith story.[7] A "Spring Special" flip book 'issue' of Warrior was published in #67 of Skinn's Comics International in 1996, featuring previously completed but unpublished Big Ben and Liberators strips.

In 2018, Skinn produced a limited edition facsimile of Warrior's original dummy issue.[49][50]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Steve Moore would contribute both under his own name and his pseudonym Pedro Henry.

References

[edit]- ^ Skinn, Dez. "WARRIOR: TAKE ONE". DezSkinn.com. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ^ "'Marvel Revolution' in England". The Comics Journal (#45): 14. March 1979.

- ^ "Dez Skinn Leaves Marvel U.K.". The Comics Journal (#54): 15. March 1980.

- ^ "Interview: The Past, Present, and Future of Dez Skinn". Major Spoilers. 23 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Khoury, George (2001). "Reign of the Warrior King". Kimota! The Miracleman Companion. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781605490274.

- ^ Harvey, Allan (June 2009). "Blood and Sapphires: The Rise and Demise of Marvelman". Back Issue! (34). TwoMorrows Publishing: 69–76.

- ^ a b c Khoury, George (2001). "The Architect of Miracleman". Kimota! The Miracleman Companion. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781605490274.

- ^ Skinn, Dez (w). "Freedom's Road - Editorial" Warrior, no. 1 (March 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Warriors All" Warrior, no. 1 (March 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 6 (October 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b c "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 12 (August 1983). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 15 (November 1983). Quality Communications.

- ^ Skinn, Dez (w). "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 2 (April 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b c Skinn, Dez (w). "All Change" Warrior, no. 5 (September 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b c d Rich Johnston (5 October 2022). "Marvel Brings Back Dez Skinn & Ian Gibson's Big Ben To Miracleman". Bleeding Cool.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Richard J. Arndt. "Warrior Index". Enjolrasworld.

- ^ a b "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 13 (September 1983). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Sweat Shop Talk" Warrior, no. 15 (November 1983). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Sweat Shop Talk II" Warrior, no. 16 (December 1983). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Sweat Shop Talk III" Warrior, no. 17 (March 1984). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Sweat Shop Talk IV" Warrior, no. 18 (April 1984). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Sweat Shop Talk V" Warrior, no. 19 (June 1984). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b c d Khoury, George (2001). "A Chronology of Everything (almost)". Kimota! The Miracleman Companion. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781605490274.

- ^ a b Plowright, Frank (January 1, 1985). "Warrior". Amazing Heroes. No. 62. Redbeard, Inc.

- ^ "With One Magic Word, Part Two: The Miraculous Revival of Marvelman". Tor.com. 15 July 2010.

- ^ Skinn, Dez (w). "Editorial" Warrior, no. 25 (December 1984). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b "Miracleman #4 To Include Marvelman Summer Special And Warpsmith Stories From A1". Bleeding Cool. 14 February 2014.

- ^ "Axel Pressbutton". Grand Comics Database.

- ^ "Laser Eraser and Pressbutton". Grand Comics Database.

- ^ a b "Newsline". Amazing Heroes. No. 96. Fantagraphics Books. June 1, 1986.

- ^ "Art For Art's Sake # 149: Celebrating The Art Of Garry Leach – Warpsmiths, Global Rescue Organisations, And; Sweaty Little Alien Perverts". Comicon.com. 9 April 2022.

- ^ "Garry Leach: A Life in Comics". The Comics Journal. 18 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 14 (October 1983). Quality Communications.

- ^ "1984". Eagle Awards. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012.

- ^ "Newsflashes". Amazing Heroes. No. 77. Redbeard, Inc. August 15, 1985.

- ^ Barr, Mike W. (October 2010). "Department of Corrections". Back Issue! (44). TwoMorrows Publishing: 78.

- ^ a b c "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 5 (September 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 7 (November 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 10 (April 1983). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 24 (November 1984). Quality Communications.

- ^ a b "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 3 (July 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 9 (January 1983). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 4 (Summer Special 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ "Dispatches" Warrior, no. 8 (December 1982). Quality Communications.

- ^ "30 Year Flashback: WARRIOR No.1". Blimey! The Blog of British Comics. 14 March 2012.

- ^ "Brawler: The New UK Anthology With Aspirations To Be Warrior". Comicon.com. 7 May 2019.

- ^ "'No Cricket Strips Here!' An Interview with Dez Skinn" (PDF). University of Dundee.

- ^ "Newsflashes". Amazing Heroes. No. 69. Fantagraphics Books. April 15, 1985.

- ^ "Warrior #0 - How it all began, available now". Comic Book News UK.

- ^ "Warrior is back (kind of!)". Comic Scene. 27 July 2018.

External links

[edit]- Warrior at the Grand Comics Database

- Warrior background on Dez Skinn's site

- Warrior bibliography and interview with Dez Skinn by Richard J. Arndt at Enjolrasworld.com

- British comics titles

- 1982 comics debuts

- 1985 comics endings

- Fantasy comics

- Science fiction comics

- British comics

- Comics magazines published in the United Kingdom

- Comics publications

- Comics anthologies

- Defunct British comics

- Magazines established in 1982

- Magazines disestablished in 1985

- Miracleman

- Monthly magazines published in the United Kingdom

- Superhero comics

- Warrior (comics)