Bhima

| Bhima | |

|---|---|

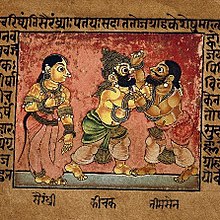

An oleograph of Bhima by Ravi Varma Press | |

| Personal Information | |

| Affiliation | Pandavas |

| Weapon | |

| Family | Parents Brothers (Kunti)

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | Sons

|

| Relatives | |

Bhima (Sanskrit: भीम, IAST: Bhīma), also known as Bhimasena (Sanskrit: भीमसेन, IAST: Bhīmasena), is a divine hero and one of the most prominent figures in the Hindu epic Mahabharata, renowned for his incredible strength, fierce loyalty, and key role in the epic’s narrative. As the second of the five Pandava brothers, Bhima was born to Kunti—the wife of King Pandu—through the blessings of Vayu, the wind god, which bestowed upon him superhuman strength from birth. His rivalry with the Kauravas, especially Duryodhana, defined much of his life, with this tension ultimately erupting in the Kurukshetra War, where Bhima killed all hundred Kaurava brothers.[1]

Bhima’s life was filled with extraordinary episodes that showcased his unmatched strength and bravery. From childhood, where he was rescued by the Nagas (divine serpents) after being poisoned, to his victories over formidable foes like Bakasura, Hidimba, and Jarasandha, Bhima’s adventures are integral to the Mahabharata’s storyline. His raw, earthy nature is reflected in the brutal slaying of his enemies, his immense appetite and his marriage with Hidimbi, a rakshasi (a supernatural being known to consume humans), who bore him a son, Ghatotkacha, a powerful warrior who would later play a significant role in the Kurukshetra War.[1]

Despite his immense physical strength, Bhima was deeply loyal and protective towards his family, particularly towards Draupadi, the common wife of the Pandavas. When Draupadi was humiliated in the Kaurava court, Bhima swore vengeance. He vowed to drink Dushasana’s blood and smash Duryodhana’s thigh, and years later, he fulfilled these vows during the Kurukshetra War. Bhima’s fierce devotion to Draupadi was also evident when he killed Kichaka, who had molested her during the Pandavas' year in disguise at the court of King Virata.[1]

A master of mace combat, Bhima was considered one of the strongest warriors of his time, with his strength often compared to that of thousands of elephants. Yet, despite his brute force, Bhima also embodied a strong sense of justice and duty, which guided his actions throughout the epic. After the war, Bhima aided his brother Yudhishthira in ruling the kingdom and stood by his brother when he later renounced the throne. Bhima accompanied Yudhishthira and the other Pandavas on their final journey to the Himalayas, where he eventually succumbed to his flaw of gluttony. His character endures in Indian and Javanese cultures as a symbol of immense power, righteous anger, and unwavering loyalty.[1]

Etymology and epithets

[edit]The word Bhīma in Sanskrit means "terrifying," "formidable," or "fearsome," describing someone who inspires awe or fear through their sheer strength or power. In the Mahabharata, Bhima is renowned for his vast size, immense physical strength and fierce nature.[2] The suffix sena is often appended to his name, forming Bhīmasena, which can be literally interpreted as "one who possesses a formidable army.".[2]

In the Mahabharata, Bhima is referred to by several synonyms, including:[3][2]

- Vṛkodara — 'wolf bellied', referring to his large appetite

- Anilātmaja, Mārutātmaja, Māruti, Pavanātmaja, Prabhañjanasuta, Samīraṇasuta, Vāyuputra, Vāyusuta — all meaning 'son of the wind god'

- Kaunteya, Pārtha — meaning 'son of Pritha or Kunti'

- Arjunāgraja, Arjunapūrvaja — 'elder brother of Arjuna'

- Acyutānuja — younger brother of Achyuta

- Vallava — 'cook'

- Pāṇḍava — 'a descendant of Pandu'

- Bhīmadhanvā — 'having a formidable bow'

- Jaya — 'victory'

- Kaurava — 'a descendant of Kuru', though this term is more prominently used for his cousins—the sons of Dhritarashtra

- Kuśaśārdūla — 'fierce like a tiger'

- Rākṣasakaṇṭaka — 'one who is a torment to the demons'

Literary background

[edit]Bhima is a significant character in the Mahabharata, one of the Sanskrit epics from the Indian subcontinent. It mainly narrates the events and aftermath of the Kurukshetra War, a war of succession between two groups of princely cousins, the Kauravas and the Pandavas. The work is written in Classical Sanskrit and is a composite work of revisions, editing and interpolations over many centuries. The oldest parts in the surviving version of the text may date to near 400 BCE.[4]

The Mahabharata manuscripts exist in numerous versions, wherein the specifics and details of major characters and episodes vary, often significantly. Except for the sections containing the Bhagavad Gita which is remarkably consistent between the numerous manuscripts, the rest of the epic exists in many versions.[5] The differences between the Northern and Southern recensions are particularly significant, with the Southern manuscripts more profuse and longer. Scholars have attempted to construct a critical edition, relying mostly on a study of the "Bombay" edition, the "Poona" edition, the "Calcutta" edition and the "south Indian" editions of the manuscripts. The most accepted version is one prepared by scholars led by Vishnu Sukthankar at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, preserved at Kyoto University, Cambridge University and various Indian universities.[6]

Bhima also appears in few of the later written Puranic scriptures, most prominent being the Krishna-related Bhagavata Purana.[7]

Biography

[edit]Birth and early life

[edit]

Bhima was the second of the five Pandava brothers, the putative sons of retired Kuru king Pandu, and was born to Kunti with divine intervention due to Pandu's inability to conceive. According to the epic, Kunti invoked the wind god, Vayu, using a mantra provided by the sage Durvasa, resulting in Bhima's birth. This divine connection bestowed upon him immense physical strength. At the time of his birth, a celestine prophecy declared that he would become the mightiest warrior. A notable incident in his infancy underscored his extraordinary strength: when he accidentally fell from his mother’s lap onto a rock, the rock shattered into pieces while Bhima remained unscathed. This event served as an early indication of his formidable abilities.[3]

After Pandu's demise in the forest, the Pandavas were raised alongside their cousins, Kauravas, in Hastinapura, the capital of Kuru. During his childhood, Bhima's strength was frequently displayed, often to the dismay of the Kauravas, particularly Duryodhana. Bhima's physical prowess frequently led to his victories in their childhood games, resulting in animosity and jealousy among the Kauravas. This enmity culminated in a plot by Duryodhana, who conspired to eliminate Bhima. In one such plot, Bhima was given poisoned food and thrown into the Ganges River while unconscious. However, this plan inadvertently led to Bhima's encounter with the Nagas (divine serpents) in their underwater realm. As Bhima descended into the river's depths, he reached the Naga realm, where the serpents bit him. Their venom neutralised the poison in his body, effectively reviving him. In this realm, Bhima met Aryaka, a Naga chieftain and his maternal relative. Recognising Bhima's divine heritage, Aryaka introduced him to Vasuki, the king of the Nagas. Impressed by Bhima's lineage and potential, Vasuki offered him a divine elixir. Bhima consumed eight pots of this elixir, thereby acquiring the strength of a thousand elephants. He spent eight days in the Naga realm to fully assimilate this power. On the ninth day, the Nagas, honouring his newfound strength, returned Bhima to Hastinapura, where he rejoined his family.[3]

In Hastinapura, Bhima, along with his brothers, was trained in the arts of warfare under the tutelage of Dronacharya, the royal guru. Bhima specialised in the use of the mace (gada) and became an unmatched mace fighter. Additionally, he received advanced training from Balarama, known for his expertise in mace combat. Bhima's training also included proficiency in various other weapons, establishing him as a versatile warrior.[3][8]

Bhima was also renowned for his giant appetite – at times, half of the total food consumed by the Pandavas was eaten by him.[9]

Hiding and encounters with Rakshasas

[edit]

The rivalry between the Pandavas and the Kauravas intensified as they grew older. Bhima's physical strength and assertiveness were sources of constant irritation for Duryodhana, who viewed him as a significant threat. The poisoning incident was one of several attempts by the Kauravas to eliminate Bhima. Another major scheme involved sending the Pandavas, along with Kunti, to Varanavata, where they were placed in a palace made of lac, known as Lakshagraha, with the intention of burning them alive. However, the Pandavas, forewarned by their uncle Vidura, managed to escape through a secret tunnel they had prepared, marking the beginning of their period of concealment to avoid further problems from the Kauravas.[3][10]

After their escape from the burning Lakshagraha, the Pandavas, accompanied by their mother Kunti, traversed the forest to avoid further threats from the Kauravas. During their journey, Kunti and her sons, except Bhima, were overcome with fatigue. Demonstrating his exceptional strength, Bhima carried his mother and brothers on his shoulders through the forest. Their journey led them to the Kamyaka forest, inhabited by the Rakshasa (here, man-eating race) Hidimba and his sister Hidimbi. While the Pandavas rested under a tree, Hidimba, who desired to consume them, dispatched his sister Hidimbi to lure them. However, upon encountering Bhima, Hidimbi was struck by his physical appearance and power, and she proposed marriage to him. When Hidimba discovered her intentions, he became enraged and attacked Bhima. Bhima engaged in combat with Hidimba and, after a fierce battle, killed him. Moved by Hidimbi's plight, Kunti consented to Bhima's marriage to her, on the condition that he would rejoin his family after some time. Bhima and Hidimbi had a son, Ghatotkacha, who later became a significant ally of the Pandavas.[3]

Following this episode, the Pandavas proceeded to the village of Ekachakra, where they lived incognito. During their stay, Bhima encountered and killed the Rakshasa Baka, who had been terrorising the villagers by eating them one by one.[3][11][12]

Marriages and children

[edit]The Mahabhrata mentions three wives of Bhima-Hidimbi, Draupadi and Valandhara, with whom he had one son each. Bhima's first wife, Hidimbi, also known as Hidimbā, was from the Rakshasa race—supernatural beings typically associated with evil deeds, such as consuming humans. Together, they had a son named Ghatotkacha (see previous section for details). Both Hidimbi and Ghatotkacha are notable exceptions, exhibiting benevolent qualities despite their Rakshasa origins.[3][1]

Draupadi was the daughter of King Drupada of Panchala, who held a svayamvara, an ancient ceremony in which a princess could choose her husband from among assembled suitors. During their hiding, they heard of it and went to Panchala to attend it in disguise. During the svayamvara, numerous princes and warriors failed to fulfil the challenge set by King Drupada. However, Arjuna, disguised as a Brahmin, succeeded in the archery challenge, winning Draupadi's hand. The Pandavas, who were in exile and disguised as Brahmins at the time, returned to their temporary abode with Draupadi. In a twist of events, Kunti, unaware of what Arjuna had won, instructed her sons to "share the alms" equally among them. Adhering to their mother's words, the Pandavas agreed to marry Draupadi collectively. Thus, Draupadi became the wife of all five Pandavas, a union that was sanctified by divine mandate. Bhima, being one of her husbands, was known for his deep affection and protective nature toward Draupadi throughout their lives. From Draupadi, Bhima fathered Sutasoma.[3]

Bhima's other wife Valandhara, the daughter of King of Kashi, was won by him at her svayamvara contest. They had a son named Savarga.[3][13][14] The Bhagavata Purana records Valandhara as Kali and Savarga as Sarvagata.[7]

Conquest for Rajasuya

[edit]

After their marriage to Draupadi, the Pandavas' survival was disclosed in Hastinapura. This was followed by the division of the kingdom, with Pandavas establishing a new city called Indraprastha. Yudhishthira, the eldest Pandava, aspired to perform the Rajasuya Yajna, a royal sacrifice that would establish him as an emperor. For this endeavour, he needed to assert his dominance over other kings and obtain their allegiance. Bhima played a crucial role in this military campaign. He was tasked with subjugating the kingdoms in the eastern region of the sub-continent,[3] since Bhishma—the Grandsire of the Kuru princes— thought the easterners were skilled in fighting from the backs of elephants and in fighting with bare arms. He deemed Bhima to be the most ideal person to wage wars in that region. The Mahabharata mentions several kingdoms to the east of Indraprastha which were conquered by Bhima.[10][15]

In his eastern campaign, Bhima, with the support of a mighty army, first moved diplomatically, beginning with the Panchalas, where he conciliated the tribe without conflict. From there, he swiftly vanquished the Gandakas, Videhas, and Dasarnas. In the Dasarna region, Bhima engaged in a notable battle with King Sudharman, who, after a fierce fight, was so impressed by Bhima's prowess that he was appointed commander of Bhima’s forces. Bhima’s conquest continued as he defeated Rochamana, the king of Aswamedha, subjugating the entire eastern region. He then marched into Pulinda, bringing the kings Sukumara and Sumitra under his sway.[16]

Bhima’s encounter with Shishupala, the king of Chedi, was peaceful, as Sisupala welcomed him and offered his kingdom. Bhima stayed for thirty nights before continuing his campaign, subjugating King Srenimat of Kumara and Vrihadvala, the king of Kosala, followed by the conquest of Ayodhya, where he defeated King Dirghayaghna. His victories extended to Northern Kosalas, Gopalakaksha, and the Mallas. As he approached the foothills of the Himalayas, he subjugated Bhallata and the Suktimanta mountains.[16][10]

Bhima's next set of conquests involved the kingdom of Kasi, where he vanquished King Suvahu, followed by the defeat of King Kratha of Suparsa. He continued to subdue regions like Matsya, Maladas, and Pasubhumi, before moving on to conquer Madahara, Mahidara, and the Somadheyas. His campaign in the north included the conquest of Vatsabhumi, Bhargas, Nishadas, and Manimat, along with Southern Mallas and the Bhagauanta mountains. Diplomatically, Bhima subdued the Sarmakas and Varmakas, while in Videha, he easily brought King Janaka under his control. He also conquered the Sakas and various barbarian tribes. His military prowess continued with the defeat of seven kings of the Kiratas near the Indra mountain, as well as the Submas and Prasuhmas. On his way to Magadha, he subdued the kings Danda and Dandadhara.[10]

Jarasandha, ruler of the Magadha empire and an enemy of teh Pandavas main ally Krishna, posed a significant obstacle to Yudhishthira when the latter sought to perform the Rajasuya Yajna. As a formidable and powerful warrior, his elimination was deemed essential for the Pandavas' success. To address this challenge, Krishna, Bhima, and Arjuna, disguised as Brahmins, traveled to Magadha to confront Jarasandha. Upon meeting him, Jarasandha inquired about their true intentions, at which point the trio revealed their identities. Krishna then issued a challenge to Jarasandha for a duel, offering him the choice of any one opponent. Jarasandha selected Bhima, recognizing him as a worthy adversary in combat. Both Bhima and Jarasandha were renowned wrestlers, and their duel extended over several days, with neither willing to concede. Despite gaining the upper hand, Bhima found himself unable to kill Jarasandha. Seeking guidance, Bhima looked toward Krishna, who symbolically picked up a twig, split it into two halves, and threw the pieces in opposite directions. Bhima, interpreting this gesture, followed suit by bisecting Jarasandha’s body and scattering the halves apart, preventing them from reuniting. As a result, Jarasandha was killed.[3] Jarasandha had previously imprisoned 100 kings, preparing them for sacrifice as part of his enmity with Krishna. His death at Bhima's hands liberated these kings, who, in gratitude, pledged their allegiance to Yudhishthira, acknowledging him as the Chakravarti, or universal ruler.[17]

Afterwards, Bhima then conquered Anga after defeating it king Karna. He later slew the mighty king of Madagiri. He further vanquished powerful rulers such as Vasudeva of Pundra, Mahaujah of Kausika-kachchha, and the king of Vanga. Additional conquests included Samudrasena, Chandrasena, and Tamralipta, as well as the kings of Karvatas and Suhmas. Finally, Bhima subdued the Mlechchha tribes along the sea coast and in marshy regions, gathering vast amounts of wealth from the Lohity region before returning to Indraprastha, where he offered the riches to Yudhishthira.[10]

Yudhishthira was able to perform the Rajasuya Yajna successfully. During the grand ceremony, Bhima's valor was acknowledged, and he played a prominent role in the various rituals and the protection of the sacrificial arena. However, the Rajasuya Yajna also sowed the seeds of future conflict. During the ceremony, a dispute arose regarding the distribution of royal honours. Bhima notably supported Krishna in the ensuing altercation with Shishupala, a vocal critic of Krishna and an antagonist to the Pandavas.[3] Later, Duryodhana fell into a water pool, Bhima, along with the twins, laughed at him.[18]

Game of Dice and vows to slay the Kauravas

[edit]The splendour of Yudhishthira's Rajasuya Yajna and the prosperity of the Pandavas caused intense jealousy among the Kauravas, particularly Duryodhana. Seeking to usurp the Pandavas' power and wealth, Duryodhana, with the counsel of his maternal uncle Shakuni, invited Yudhishthira to a game of dice. Despite his misgivings, Yudhishthira accepted the challenge, driven by the codes of Kshatriya honour and hospitality. The game of dice was a turning point in the epic. Shakuni, who played on behalf of Duryodhana, used deceitful means to ensure Yudhishthira's defeat. As the game progressed, Yudhishthira lost his kingdom, wealth, and even his brothers, including Bhima, one by one. Eventually, he wagered Draupadi and lost her as well.[3][19]

The Kauravas' subsequent treatment of Draupadi, especially the attempt to disrobe her in the assembly hall, provoked Bhima's fury. Bhima was the only one from the Pandavas' side to protest against the wrongdoing, with Vidura and Vikarna raising objections from the Kauravas' side. Unable to act due to his bondage through the game, Bhima became extremely upset with Yudhishthira and asked Sahadeva to bring fire so that he could "burn Yudhishthira’s hands." When Arjuna pacified, Bhima responded by stating that when elders committed mistakes, verbally insulting them was equivalent to punishing them. Bhima also contemplated killing the Kauravas on the spot. However, Arjuna calmed him down, and Yudhisthira firmly prohibited any confrontation.[19]

After the Kauravas exiled the Pandavas for thirteen years, Bhima swore terrible oaths of vengeance. He vowed to kill Duryodhana by breaking his thigh, a reference to Duryodhana's insulting gesture during the dice game, when he exposed his thigh (a euphemism for the genitals[1]) and commanded Draupadi to sit on his lap. Bhima also swore to avenge Draupadi's humiliation by drinking the blood of Dushasana, who had forcibly dragged her by her hair and attempted to disrobe her in the Kauravas' assembly.[19][20]

Exile and Life in the Forest

[edit]

During their twelve-year exile in the forest following their loss in the game of dice, the Pandavas encountered numerous adversities and engaged in various significant events. Bhima, with his immense strength and courage, was instrumental in addressing many challenges that arose during this period.[3]

A prominent encounter during their exile was with the Rakshasa Kirmira, the brother of the Rakshasa Baka, whom Bhima had previously slain in Ekachakra. Kirmira, seeking revenge for his brother's death, confronted the Pandavas in the Kamyaka forest. Bhima engaged in a fierce battle with Kirmira and ultimately killed him, thereby eliminating the threat he posed.[3][21]

Another significant event involved the Pandavas' quest to obtain divine weapons. At one point, Arjuna departed to the Himalayas to undertake severe penance in order to acquire celestial weapons from the god Shiva. During Arjuna's prolonged absence, Bhima and the remaining Pandavas grew increasingly concerned for his safety. The Pandavas ventured to Mount Gandhamadana in search of Arjuna. During this arduous journey, they encountered numerous challenges, including fatigue and harsh terrains. At one point, Draupadi fainted from exhaustion. Bhima then invoked his son Ghatotkacha, who promptly arrived and assisted the Pandavas. Ghatotkacha carried the Pandavas on his shoulders, allowing them to continue their journey with greater ease. Their journey eventually led them to the ashrama of Nara and Narayana. While resting there, Bhima noticed a fragrant Saugandhika flower, which had been carried to Draupadi by the northeast wind. Draupadi expressed her desire to possess more of these flowers. To fulfil her wish, Bhima set out in the northeast direction toward the Saugandhika forest. This journey brought Bhima to Kadalivana, where he encountered Hanuman, his half-brother, as both were sons of the wind god, Vayu. Initially, Hanuman tested Bhima's strength and humility by blocking his path with his tail. Despite Bhima's efforts, he was unable to move Hanuman's tail. Recognising the limits of his strength, Bhima humbled himself, prompting Hanuman to reveal his true identity. Hanuman blessed Bhima and provided him guidance to the Saugandhika forest. Following this encounter, Bhima ventured into the forest, overcame the Rakshasas known as Krodhavasas guarding it, and successfully collected the flowers, which he later presented to Draupadi.[3][22]

Another notable event during the Pandavas' exile involved the abduction attempt by Jayadratha, the king of Sindhu. While the Pandavas were away hunting, Jayadratha encountered Draupadi alone and abducted her. On learning of this, Bhima, along with his brothers, pursued and confronted Jayadratha. Bhima overpowered Jayadratha's forces, captured him, and expressed a desire to kill him for his transgression. However, Yudhishthira intervened, advocating for a less violent resolution. Consequently, Bhima and his brothers humiliated Jayadratha by shaving his head, leaving him with a mark of disgrace before releasing him.[3]

During their time in the forest, the Pandavas also encountered various sages and divine beings, from whom they received blessings and spiritual knowledge. These interactions not only provided them with guidance but also augmented their abilities to face future challenges. One significant episode was their encounter with Nahusha, a former king who had been transformed into a python due to a curse. Bhima, while traversing the forest, was captured by this python. Despite his strength, Bhima was unable to free himself. Yudhishthira arrived and, recognising the being as Nahusha, engaged in a dialogue with him. Through Yudhishthira's wisdom, Nahusha was released from his curse and restored to his original form.[3]

The Pandavas also had to contend with the ever-present threat of the Kauravas during their exile. On one occasion, the Kauravas, led by Duryodhana, encamped near the Pandavas' dwelling in Dvaitavana. During this encampment, Duryodhana and his forces clashed with the Gandharva Chitrasena. Duryodhana was captured by the Gandharvas, and upon hearing this, Bhima expressed amusement at his plight. However, at Yudhishthira's behest, Bhima and the Pandavas intervened and freed Duryodhana from captivity. Although reluctant to assist their adversary, the Pandavas acted in accordance with their dharma, thereby upholding their principles.[3]

In another minor incident in the epic, Jatasura, a rakshasa disguised as a Brahmin abducted Yudhishthira, Draupadi and the twin brothers, Nakula, and Sahadeva during their stay at Badarikashrama. His objective was to seize the weapons of the Pandavas. Bhima, who was gone hunting during the abduction, was deeply upset when he came to know of Jatasura's evil act on his return. A fierce encounter followed between the two gigantic warriors, where Bhima emerged victorious by decapitating Jatasura and crushing his body.[23][24]

Incognito life in Virata's kingdom

[edit]

After completing their twelve-year exile, the Pandavas entered their thirteenth year, during which they were required to live incognito. They sought refuge in the kingdom of Matsya, ruled by King Virata, and assumed various disguises. Bhima took on the role of Vallabha, a cook, and wrestler in King Virata's palace. Within themselves, Pandavas called him Jayanta. His primary duties involved working in the royal kitchens, though his position as a wrestler occasionally necessitated the display of his physical prowess.[25] There was a wrestling bout where a wrestler from a different state, Jimuta proved to be invincible. Much to the delight of King Virata and his subjects, Bhima challenged Jimuta and knocked him out in no time. This greatly enhanced the reputation of the Pandavas in unfamiliar territory.[26]

A significant incident during this period was Bhima's encounter with Kichaka, the brother-in-law of King Virata. Kichaka developed an infatuation with Draupadi, who was serving in the palace under the guise of a maid named Sairandhri. Kichaka's advances toward Draupadi escalated and he tried to sexually assault her, prompting her to seek Bhima's protection. Bhima devised a plan to eliminate Kichaka without revealing their true identities. He arranged for Draupadi to lure Kichaka into a secluded area, where Bhima, disguised, awaited him. A physical confrontation ensued, during which Bhima killed Kichaka. This incident was carried out discreetly to avoid compromising the Pandavas' incognito status. Kichaka’s brothers blamed Sairandhri (Draupadi) for his death and tried to forcefully cremate her along with Kichaka, but Bhima slew them and rescued Draupadi.[3]

Despite Kichaka's death raising suspicions within the palace, the Pandavas successfully maintained their disguises. Towards the end of their incognito year, the Kauravas and Trigartas raided the Matsya kingdom's cattle in an attempt to expose the Pandavas. Bhima, along with his brothers, defended the kingdom, ensuring that their true identities remained hidden until the incognito period concluded.[3]

The Kurukshetra War

[edit]Following the Pandavas' return from their exile, the Kauravas refused to restore their share of the kingdom. This refusal led to the inevitability of the Kurukshetra War. Bhima played a significant role in the events leading up to the war and was a key combatant throughout the eighteen days of conflict, which are documented in four books of the Mahabharata-Bhisma Parva, Drona Parva, Karna Parva and Shalya Parva.

Before the war commenced, discussions were held among the Pandavas and their allies regarding the strategy and leadership of the army. Bhima suggested that Shikhandi, who had the ability to challenge Bhishma due to Bhishma's oath not to fight against a woman or someone perceived as a woman, should lead the Pandava forces. However, Yudhishthira and Arjuna decided to appoint Dhrishtadyumna as the commander-in-chief.[3] Bhima’s chariot was driven by his charioteer, Vishoka, and bore a flag with a gigantic lion in silver, its eyes made of lapis lazuli. His chariot was yoked to horses described as being as black as bears or black antelopes.[27][28] Bhima wielded a celestial bow named Vayavya, gifted to him by his divine father, Vayu, and also possessed the massive conch named Paundra. Additionally, he wielded a colossal mace, said to have the strength of a hundred thousand maces, which had been presented to him by Mayasura.

Before hostilities broke out, Krishna sought a final compromise to avoid war. During these peace talks, Bhima expressed his opinion that peace was preferable to war (Udyoga Parva, Chapter 74). However, he also asserted that he was prepared for battle and spoke confidently about his prowess in the upcoming conflict (Udyoga Parva, Chapter 76). When Duryodhana sent Uluka with a message to the Pandavas, Bhima responded with an insulting reply, rejecting any form of submission or negotiation (Udyoga Parva, Chapter 163).[3]

Bhishma Parva (1st - 11th days)

[edit]

On the first day of the Kurukshetra War, Bhima confronted Duryodhana in a direct duel. The clash between the two warriors set the stage for the fierce rivalry that would continue throughout the battle (Chapter 45, Verse 19). During this early phase, Bhima’s war cry was described as so powerful that it caused the world to shudder (Chapter 44, Verse 8). Bhima then engaged in combat with the forces of the Kalingas. In this engagement, he killed the Kalinga prince Shakradeva (Chapter 54, Verse 24). Continuing his assault on the Kalinga army, Bhima also killed another key warrior, Bhanuman (Chapter 54, Verse 39). In the same battle, Bhima targeted the chariot of King Shrutayus, slaying warriors named Satyadeva and Shalya (distinct from another warrior also named Shalya), who were guarding the chariot wheels (Chapter 54, Verse 76). Following these encounters, Bhima proceeded to kill Ketuman (Chapter 54, Verse 77). In addition to fighting individual warriors, Bhima turned his attention to the Kaurava elephant division. He decimated the division, causing a significant number of casualties and resulting in what was described as rivers of blood flowing on the battlefield (Chapter 54, Verse 103).[3]

Later in the war, Bhima once again faced Duryodhana in combat. In this confrontation, he successfully defeated Duryodhana (Chapter 58, Verse 16). Bhima also engaged Bhishma, the commander-in-chief of the Kaurava army, in combat on multiple occasions (Chapter 63, Verse 1). This battle was marked by intensity, with Bhima attempting to overpower Bhishma, though Bhishma remained undefeated. Bhima then targeted the Kaurava brothers in a specific engagement, where he killed eight sons of Dhritarashtra. The names of those killed in this battle were Senapati, Jarasandha, Sushena, Ugra, Virabahu, Bhima, Bhimaratha, and Sulocana (Chapter 64, Verse 32). In another subsequent battle, Bhima fought against Bhishma once more (Chapter 72, Verse 21). He continued to engage Duryodhana, defeating him again in another encounter (Chapter 79, Verse 11).[3]

In the course of the war, Bhima defeated Kritavarma (Chapter 82, Verse 60). Later, in his engagement with Bhishma, Bhima killed Bhishma’s charioteer (Chapter 88, Verse 12). Following this, Bhima killed eight more sons of Dhritarashtra in another fierce confrontation (Chapter 88, Verse 13). Bhima’s clashes also included a direct engagement with Dronacharya. In this battle, Bhima struck Dronacharya with such force that the preceptor fell unconscious (Chapter 94, Verse 18). Bhima continued his assault on the Kaurava brothers, killing nine more sons of Dhritarashtra (Chapter 96, Verse 23). In another encounter, Bhima faced Bahlika, whom he defeated in combat (Chapter 104, Verse 18). He also engaged Bhurishravas in a duel (Chapter 110, Verse 10). Bhima's continued offensive efforts led to the killing of ten Maharathis (great chariot warriors) of the Kaurava army in a single battle (Chapter 113).[3]

Drona Parva (12th - 15th days)

[edit]

Dhritarashtra, the Kaurava patriarch, acknowledged Bhima's prowess in the Drona Parva (Chapter 10). Bhima fought with Vivinsati in a combat engagement (Chapter 14, Verse 27). He then entered into a club fight with Shalya, defeating him (Chapter 15, Verse 8). Following this, Bhima fought with Durmarshana (Chapter 25, Verse 5). In this phase of the war, Bhima also killed Anga, the King of the Mleccha tribe (Chapter 26, Verse 17).[3]

Bhima's confrontation with Bhagadatta's elephant was a notable encounter in which he was defeated and forced to retreat temporarily (Chapter 26, Verse 19). Later, he targeted Karna's forces, attacking them and killing fifteen warriors in the process (Chapter 32, Verse 32). Bhima then fought against Vivinsati, Chitrasena, and Vikarṇa (Chapter 96, Verse 31). In another engagement, Bhima fought Alambusha and emerged victorious (Chapter 106, Verse 16). Bhima then clashed with Kritavarma (Chapter 114, Verse 67). During a moment of distress, Bhima consoled Yudhishthira, who was facing a crisis of confidence (Chapter 126, Verse 32). Bhima confronted Drona again and was able to defeat him (Chapter 127, Verse 42). Following this battle, he killed a group of warriors, including Kundabhedi, Sushena, Dirghalochana, Vrindaraka, Abhaya, Raudrakarma, Durvimocana, Vinda, Anuvinda, Suvarma, and Sudarshana (Chapter 127, Verse 60). In a display of combat skill, Bhima threw Dronacharya off his chariot eight times (Chapter 128, Verse 18). Bhima engaged Karna in battle and succeeded in defeating him (Chapter 122). In a separate battle, Bhima killed Dussala, another warrior (Chapter 129). He later faced Karna once again (Chapter 131). In subsequent engagements, Bhima killed Durjaya (Chapter 133, Verse 13) and Durmukha (Chapter 134, Verse 20). He continued his campaign against the Kaurava brothers, killing Durmarshana, Dussaha, Durmada, Durdhara, and Jaya (Chapter 135, Verse 30).[3]

Bhima fought Karna repeatedly, destroying many of his bows during their encounters (Chapter 139, Verse 19). In an aggressive maneuver, Bhima attempted to capture Karna by jumping into his chariot (Chapter 139, Verse 74). However, during this engagement, Karna struck Bhima with such force that Bhima fell unconscious (Chapter 139, Verse 91). Subsequently, Bhima killed the prince of Kalinga by thrashing and kicking him (Chapter 155, Verse 24). He continued his offensive against key warriors, pushing and beating Jayarata, Dhruva, Durmada, and Dushkarna to death (Chapter 155). Bhima also rendered the great hero Somadatta unconscious with his club (Chapter 157, Verse 10). Bhima encountered Vikarna along with seven Kaurava brothers . In the battle that ensued, Vikarna was killed. Bhima grieved Vikarna's death by praising his noble deeds.[29] In this chapter, Bhima also killed Bahlika (Chapter 157, Verse 11)[30] and other warriors including Nagadatta, Dridharatha, Mahabahu, Ayobhuja, Dridha, Suhastha, Viraja, Pramathi, Ugra, and Anuyayi (Chapter 157, Verse 16).[3]

On the 15th day of the war, Bhima attacked Duryodhana and defeated him after a fierce exchange.[31] Bhima's son Ghatotkacha was killed by Karna, leading to Bhima lament over his death.[32] Bhima then killed the elephant named Ashvatthama as part of a strategic deception to spread the false news that Drona's son, Ashvatthama, had been killed (Chapter 190, Verse 15). This ruse led to Drona's surrender and eventual downfall. Bhima then fought against the Narayanastra, a celestial weapon deployed by Ashvatthama (Chapter 199, Verse 45). During this encounter, Bhima’s charioteer was killed (Chapter 199, Verse 45).[3] Bhima was the only warrior who refused to submit to the invincible Narayanastra weapon and had to dragged to his safety by Arjuna and Krishna.[33]

Karna Parva (16th-17th days)

[edit]

In the Karna Parva, Bhima killed Kshemadhurti, the King of Kalata, in another battle (Chapter 12, Verse 25). He then fought Ashvatthama, but was struck down unconscious in this encounter (Chapter 15). Bhima killed Bhanusena, the son of Karna, in a subsequent duel (Chapter 48, Verse 27). He then killed Vivitsu, Vikata, Sama, Kratha, Nanda, and Upananda in another engagement (Chapter 51, Verse 12).[3]

Bhima once again defeated Duryodhana in battle (Chapter 61, Verse 53). During this phase of the war, he took upon himself the responsibility of the battle's outcome and directed Arjuna to guard Yudhishthira (Chapter 65, Verse 10). Bhima also defeated Shakuni in combat (Chapter 81, Verse 24). He engaged Duryodhana in another fierce encounter (Chapters 82 and 83).[3]

In a critical moment of the war, Bhima killed Dushasana, fulfilling his vow and symbolically drinking the blood from Dushasana's chest after ripping out his limbs and tearing his chest open. (Chapter 83, Verse 28).[34] Following this, Bhima killed ten more sons of Dhritarashtra: Nisangi, Kavaci, Pasi, Dandadhara, Dhanurgraha, Alolupa, Sala, Sandha, Vatavega, and Suvarcas (Chapter 84, Verse 2).Bhima continued his assault on the Kaurava forces, killing 25,000 infantrymen single-handedly in one engagement (Chapter 93, Verse 28).[3]

Shalya Parva (18th day)

[edit]

In the Shalya Parva, Bhima defeated Kritavarma in combat (Chapter 11, Verse 45). He then fought Shalya in a club fight (Chapter 12, Verse 12). Bhima once again defeated Duryodhana (Chapter 16, Verse 42). In a subsequent battle, he killed the charioteer and horses of Shalya (Chapter 17, Verse 27). Bhima then killed another 25,000 infantrymen (Chapter 19, Verse 49). He targeted the sons of Dhritarashtra, killing eleven more of them: Durmarshana, Shrutanta, Jaitra, Bhuribala, Ravi, Jayatsena, Sujata, Durvisha, Durvimocana, Duspradharsha, and Shrutavarma (Chapter 27, Verse 49).[3]

In the climactic battle of the war, Bhima engaged Duryodhana in a mace duel. Duryodhana had went and hid under a lake. The Pandavas brothers and Krishna thus went to the lake and taunted Duryodhana off his refuge. Yudhishthira proposed a final challenge to Duryodhana, to a battle against any of the Pandavas under any weapon of Duryodhana's desire. Yudhishthira also promised Duryodhana that should he win, he would reign as the next King of Hastinapura. After given the option to choose the opponent, Duryodhana chose Bhima as his opponent.[35]

Though Bhima had superior strength, Duryodhana had superior skills. Krishna reminded Arjuna about Bhima's oath to smash Duryodhana's thigh during the duel. Arjuna signaled to Bhima by slapping his thigh. Understanding that sign, Bhima threw his mace towards Duryodhana's thigh while the latter was in mid-air during a jump.[36] After defeating Duryodhana, Bhima taunted Duryodhana by kicking his head repeatedly and dancing madly.[3][37] Enraged at this sight, Balarama grabbing his plough attempted to attack Bhima, but was stopped by Krishna. Krishna convinced his brother by reminding him of Bhima's oath and the encroaching onset of the Kali Yuga.[38]

Later years and death

[edit]

After the Kurukshetra War, Bhima played a significant role in the events that followed. He pursued Ashvatthama, who had killed Draupadi's sons (including Bhima's son Sutasoma) in a night raid on the Pandava camp (Sauptika Parva, Chapter 13, Verse 16). After Ashwatthama was subdued and his powerful gem was taken from him, Bhima presented the gem to Draupadi (Sauptika Parva, Chapter 16, Verse 26), consoling her. Later, Bhima apologised to Gandhari, the mother of the Kauravas (Stri Parva, Chapter 15), and Dhritarashtra, who attempted to kill him by crushing him in a bear hug. Krishna intervened by replacing Bhima with a metal statue, and Dhritarashtra’s rage was appeased when he shattered the statue, allowing him to partially forgive him.[3]

When Yudhishthira expressed a desire to renounce the world and take up the life of a sannyasin, Bhima urged Yudhishthira to remain on the throne (Shanti Parva, Chapter 19). Yudhishthira appointed Bhima as the commander-in-chief of Hastinapura. (Shanti Parva, Chapter 41, Verse 9)[39] and settled him in the palace that had belonged to Duryodhana (Shanti Parva, Chapter 44, Verse 6). During the Ashvamedha Yajna conducted by Yudhishthira, Bhima took on the responsibility of measuring the sacrificial ground alongside the Brahmins (Ashvamedha Parva, Chapter 88, Verse 6). During this period, Babhruvahana, a son of Arjuna, visited Bhima, who sent him back with gifts of money and food grains (Ashvamedha Parva, Chapter 88, Verse 6). Bhima initially opposed Dhritarashtra's request for funds to perform riyuals for those who had died in the war, but agreed after persuasions from Dhritarashta and Yudhishthira (Ashramavasika Parva, Chapter 11, Verse 7). After Dhritarashtra, Gandhari, and Kunti retired to the forest, Bhima visited them once (Ashramavasika Parva, Chapter 23).[3]

After almost three decades, upon the onset of the Kali Yuga, the Pandavas delegated the administration of the kingdom to Parikshit, and embarked on their final journeyto the Himalayas. During the journey, Draupadi, Sahadeva, Nakula, and Arjuna each succumbed to death in succession. Bhima inquired about the cause of these deaths, and Yudhishthira provided him with appropriate explanations. When Bhima himself was on the verge of death, he questioned the reason, and Yudhishthira attributed it to Bhima’s gluttony.[3][40] In some versions of the story, Yudhishthira points out Bhima's boastfulness, gluttony, and battle-lust as the reasons for his fall. Bhima is seen among the Maruts and sitting next to his father Vayu, when Yudhisthira ascended to Svarga.[41]

Outside Indian subcontinent

[edit]Indonesia

[edit]

Bhima, also known as Werkudara in Indonesian and Javanese culture, is a prominent figure in Indonesia's wayang traditions, particularly within Javanese and Balinese cultures. Renowned for his strength, bravery, and wisdom, Bhima is portrayed as a figure who treats everyone equally, adhering to principles of honesty and loyalty. His character refrains from using refined speech or showing subservience, except in special circumstances, such as when he becomes a sage in the "Bhima Suci" play or during his meeting with Dewaruci.[42]

In Indonesia, Bhima is highly skilled in the use of various weapons, including the mace (Gada) and other divine armaments like the Pancanaka and Rujakpala. He is also endowed with supernatural powers, including Aji Bandungbandawasa and Aji Ketuglindhu. Additionally, he is known for his symbolic attire, such as the Nagabanda belt and Cinde Udaraga pants, representing his divine stature.[43]

Bhima’s presence in Indonesian mythology extends into the wayang puppet theater, where his stories are celebrated. He is depicted as the son of the wind god, Batara Bayu, and is known for his exceptional strength and ability to control the wind. Various tales recount his adventures, including his encounters with giants, his quest for divine knowledge, and his key role in the Mahabharata epic, particularly in the Baratayuda (the Javanese version of the Kurukshetra War).[42]

Bhima's image is also revered in Indonesia through various statues, such as those in Bali and at the National Museum of Indonesia. His cultural significance persists, making him a well-known figure among Javanese people, including the Javanese Muslims.[44]

Wayang story

[edit]

In the Javanese and Balinese wayang tradition, Bhima (also known as Werkudara) is a prominent and revered character, representing strength, courage, and an unwavering sense of righteousness. The wayang (shadow puppet theater) performances have transformed the story of Bhima into a narrative deeply infused with spiritual and moral themes, often differing from the classical Indian Mahabharata. In these performances, Bhima’s journey is not only physical but spiritual, as he seeks wisdom, power, and enlightenment.[42]

One of the most well-known stories in wayang featuring Bhima is his encounter with Dewaruci, a powerful spiritual episode that symbolizes Bhima's quest for inner knowledge. In this story, Bhima is tasked with finding the Tirta Amerta, the water of life, which symbolizes eternal truth. This leads him into the ocean, where he faces several trials. During this quest, Bhima meets Dewaruci, a miniature divine form of himself, who reveals the secrets of the universe to Bhima, teaching him the values of humility, inner strength, and the importance of enlightenment beyond physical might. The character of Bhima in wayang is also portrayed as a defender of the weak and a warrior who fights not only external battles but internal struggles as well. His devotion to his family, especially to his mother Kunti and brothers, is emphasized, highlighting his loyalty and dedication. His weapon of choice, the mace (gada), is a symbol of both his physical power and his ability to uphold justice.[45][42]

The wayang performances often extend Bhima’s role beyond the original Indian epic, incorporating elements of local folklore, myth, and cultural values. As such, Bhima becomes a symbol of Javanese ideals—strength tempered by wisdom, loyalty to family and community, and the pursuit of spiritual knowledge. The wayang version of Bhima is deeply ingrained in Indonesian culture, serving as a moral guide and a heroic figure whose stories resonate with audiences across generations.[42]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f James Lochtefeld The Illustrated Encyclopedia Of Hinduism.

- ^ a b c Monier-Williams, Sir Monier; Leumann, Ernst; Cappeller, Carl (1899). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages. Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House. p. 758. ISBN 978-81-208-3105-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic encyclopaedia : a comprehensive dictionary with special reference to the epic and Puranic literature. Robarts - University of Toronto. Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-0-8426-0822-0.

- ^ Brockington, J. L. (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. Brill Academic. p. 26. ISBN 978-9-00410-260-6.

- ^ Minor, Robert N. (1982). Bhagavad Gita: An Exegetical Commentary. South Asia Books. pp. l–li. ISBN 978-0-8364-0862-1. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ McGrath, Kevin (2004). The Sanskrit Hero: Karna in Epic Mahabharata. Brill Academic. pp. 19–26. ISBN 978-9-00413-729-5. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ a b Sinha, Pürnendu Narayana (1901). A Study of the Bhagavata Purana: Or, Esoteric Hinduism. Freeman & Company, Limited.

- ^ "Mahabharata Text".

- ^ Kapoor, Subodh, ed. (2002). The Indian encyclopaedia : biographical, historical, religious, administrative, ethnological, commercial and scientific (1st ed.). New Delhi: Cosmo Publications. p. 7535. ISBN 9788177552577.

- ^ a b c d e "The Mahabharata, Book 2: Sabha Parva: Jarasandhta-badha Parva: Section XXIX". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ "Kaivara | Chikkaballapur District, Government of Karnataka | India". Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ "Mahabharata Text".

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 1: Adi Parva: Sambhava Parva: Section XCV". Archived from the original on 16 January 2010.

- ^ Erin Bernstein; Kisari Mohan Ganguli (12 July 2017). The Mahabharata: A Modern Retelling: Volume I: Origins. BookRix. pp. 470–. ISBN 978-3-7438-2228-3.

- ^ The Mystery of the Mahabharata: Vol.4. India Research Press.

- ^ a b "The Mahabharata, Book 2: Sabha Parva: Jarasandhta-badha Parva: Section XXVIII". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ "Mahabharata Text".

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 2: Sabha Parva: Sisupala-badha Parva: Section XLVI". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ a b c Winternitz, Moriz (1996). A History of Indian Literature. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0264-3.

- ^ Ernest, Phillip (2006). "True Lies - Bhīma's Vows and the Revision of Memory in the "Mahābhārata's" Code". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 87: 273–282. ISSN 0378-1143. JSTOR 41692062.

- ^ "Mahabharata Text".

- ^ "Mahabharata Text".

- ^ "Mahabharata Text".

- ^ Gupta, Rashmi (2010). Tibetans in exile : struggle for human rights. New Delhi: Anamika Publishers & Distributors. p. 625. ISBN 9788179752487.

- ^ Kapoor, Subodh, ed. (2002). The Indian encyclopaedia : biographical, historical, religious, administrative, ethnological, commercial and scientific (1st ed.). New Delhi: Cosmo Publications. p. 4462. ISBN 9788177552577.

- ^ "Mahabharata Text".

- ^ "Mahabharata Text".

- ^ Kapoor, Subodh, ed. (2002). The Indian encyclopaedia : biographical, historical, religious, administrative, ethnological, commercial and scientific (1st ed.). New Delhi: Cosmo Publications. p. 4462. ISBN 9788177552713.

- ^ <"The Mahabharata, Book 7: Drona Parva: Jayadratha-Vadha Parva Parva: Section CXXXVI". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 7: Drona parva : Section 188". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 7: Drona Parva: Ghatotkacha-badha Parva: Section CLXV".

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 7: Drona parva : Section 188". Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 7: Drona Parva: Drona-vadha Parva: Section CCI".

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 8: Karna Parva: Section LXXXVIII".

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 9: Shalya Parva: Section XXXII".

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 9: Shalya Parva: Section 58".

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 9: Shalya Parva: Section 59".

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 9: Shalya Parva: Section 60".

- ^ "Mahabharata Text".

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 17: Mahaprasthanika Parva: Section II".

- ^ "The Mahabharata, Book 18: Svargarohanika Parva: Section IV".

- ^ a b c d e Suparyanto, Petrus (2019). Bhima's Mystical Quest: As a Model of Javanese Spiritual Growth. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-643-90883-4.

- ^ ""Bima Ngaji", Maknai Asal Dan Tujuan Hidup Manusia". Kembdikbud. 3 December 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ MacGregor, Neil (2011). A History of the World in 100 Objects (First American ed.). New York: Viking Press. p. 540. ISBN 978-0-670-02270-0.

- ^ Ariandini, Woro (2000), "Citra Bima dalam kebudayaan Jawa", Woro Ariandini, ISBN 9789794562130