Beyond Good & Evil (video game)

| Beyond Good & Evil | |

|---|---|

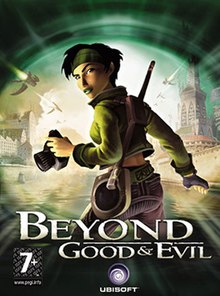

European cover art depicting the main protagonist, Jade, holding her camera | |

| Developer(s) | Ubisoft Pictures[a] Ubisoft Milan |

| Publisher(s) | Ubisoft |

| Director(s) | Michel Ancel |

| Producer(s) | Yves Guillemot |

| Designer(s) | Michel Ancel Sébastien Morin |

| Artist(s) | Florent Sacré Paul Tumelaire |

| Writer(s) | Michel Ancel Jacques Exertier |

| Composer(s) | Christophe Héral |

| Engine | Jade |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | PlayStation 2WindowsXboxGameCube Remaster Xbox 360

20th Anniversary Edition Switch, PS4, PS5, Windows, Xbox One, Xbox Series X/S June 25, 2024 |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure, Stealth game |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Beyond Good & Evil is a 2003 action-adventure game developed and published by Ubisoft for PlayStation 2, Windows, Xbox, and GameCube.[2] The story follows the adventures of Jade, an investigative reporter, martial artist, and spy hitwoman working with a resistance movement to reveal a sinister alien conspiracy. Players control Jade and other allies, solving puzzles, fighting enemies, obtaining photographic evidence and, later in the game, travelling to space.

Michel Ancel, creator of the Rayman series, envisioned the game as the first part of a trilogy. The game was developed under the codename "Project BG&E" by 30 employees of Ubisoft's studio divisions in Montpellier and Milan, with production lasting more than three years. One of the main goals of the game is to create a meaningful story while giving players much freedom, though the game adopts a relatively linear structure. The game was received poorly when it was shown at E3 2002, and it prompted the developers to change some of the game's elements, including Jade's design. Ancel also attempted to streamline the game in order to make it more commercially appealing.

Beyond Good & Evil received generally favorable reviews upon release, with critics praising the game's animation, setting, story and design, but criticizing its combat and technical issues. The game received a nomination for "Game of the Year" at the 2004 Game Developers Choice Awards. While the game was considered a commercial failure at launch, it has since developed a cult following and is even considered by some to be one of the greatest video games ever made.

A full HD remastered version of the game was released on Xbox Live Arcade in March 2011 and on PlayStation Network in June 2011. A prequel, Beyond Good and Evil 2, is in development and was announced at E3 2017.[3] A hybrid live-action/animated film adaptation is currently in the works at Netflix. Another remaster, titled the 20th Anniversary Edition, was released on June 25, 2024.

Gameplay

[edit]

Beyond Good & Evil is an action-adventure game with elements of puzzle-solving and stealth-based games.[4] The player controls the protagonist, Jade, from a third-person perspective. Jade can run, move stealthily, jump over obstacles and pits, climb ladders, push or bash doors and objects, and flatten herself against walls.[5] As Jade, the player investigates a number of installations in search of the truth about a war with an alien threat.[4]

In the game's interior spaces, the player solves puzzles and makes their way past enemies in order to reach areas containing photographic evidence.[4] Jade's main tools are her Daï-jo combat staff (a melee weapon), discs for attacking at range, and a camera.[6] Jade's health, represented by hearts, decreases when hit by enemy attacks. It can be restored using fictional food items and can be increased beyond the maximum with "PA-1s" that, when held by Jade or her companions, increases their life gauge by one heart.[7] If Jade's health is depleted, the game will restart at the last checkpoint. Certain stealth segments later in the game can automatically kill Jade if she is detected. Most stealth elements allow Jade to fight for her life if she is detected, but it's more difficult to survive this way.

At times, it is only possible to advance in the game with the help of other characters. These characters are computer-controlled, and players direct them via contextual commands.[4] For example, the player can order them to perform a "super attack", either pounding the ground to bounce enemies into the air, allowing the player to hit them from long distances, or knocking them off balance, making them vulnerable to attack.[8] These allies possess a health bar and are incapacitated if it is depleted. Jade can share some of her items, such as PA-1s, with these characters.

In addition to obtaining evidence and completing assignments, Jade's camera can take pictures of animal species in exchange for currency, and scan objects to reveal more information about the environment.[6] When the "Gyrodisk Glove" is obtained, Jade can attack enemies or activate devices from a distance by using the camera interface.[9] There are also various minigames and sub-missions offered by NPCs scattered throughout the world.[10]

A hovercraft is used to travel around the world, and also used for racing and in other minigames.[11] Later, the spaceship Beluga is acquired. The hovercraft can dock with the spaceship. Both vehicles require upgrades in order to reach new areas and progress through the game. Upgrades are purchased using pearls that are collected throughout the game, by completing missions, exploring areas, filling in the animal directory or by trading credits for them. The vehicles have a boost ability, and can be repaired using a "Repair Pod" if damaged by enemies.[12]

Plot

[edit]Setting and characters

[edit]Beyond Good & Evil takes place in the year 2435 on the mining planet of Hillys, located in a remote section of the galaxy.[13] The architecture of the city around which the game takes place is rustic European in style. The world itself combines modern elements, such as email and credit cards, with those of science fiction and fantasy, such as spacecraft and anthropomorphic animals coexisting with people.[14] As the game begins, Hillys is under siege by aliens called the "DomZ", who abduct beings and either drain their life force for power or implant them with spores to convert them into slaves.[13] Prior to the opening of the game, a military dictatorship called the "Alpha Sections" has come to power on Hillys, promising to defend the populace.[6] However, the Alpha Sections seem unable to stop the DomZ despite its public assurances. An underground resistance movement, the IRIS Network, fights the Alpha Sections, believing it to be in league with the DomZ.[15]

Beyond Good & Evil's main protagonist, Jade (voiced by Jodi Forrest), is a young photojournalist. Uncle Pey'j (voiced by David Gasman), a boar-like creature, is Jade's best friend, with whom Jade resides in an island lighthouse that doubles as a home for children orphaned by DomZ attacks, whom they care for.[6] Double H, a heavily built human IRIS operative, assists Jade during missions. He wears a military-issue suit of armor at all times. Secundo, an artificial intelligence built into Jade's storage unit, the "Synthetic-Atomic-Compressor" (SAC), offers advice and "digitizes" items. The main antagonists are the DomZ High Priest, who is the chief architect of the invasion, and Alpha Sections leader General Kehck, who uses propaganda to gain the Hillyans' trust, even as he abducts citizens to sustain the DomZ.

Story

[edit]Jade and Pey'j are taking care of the children of Hillys orphaned by the DomZ. When meditating with one of the orphans outside, a DomZ siren sounds. Jade rushes to turn the power on for the shield, but discovers that it has been deactivated due to a lack of funds. The lighthouse is left vulnerable to the meteor shower, and several DomZ creatures manage to abduct a number of the orphans. Jade is forced to fight these creatures to free the children. With Pey'j's help, she then defeats a DomZ monster that emerges from a meteor crater. The Alpha Sections arrive just after Jade defeats the monster, leaving Pey'j to grumble that they were late as usual.

Secundo finds a photography job for Jade, so she can pay to turn the power back on for the shield. The job involves cataloging all the species on Hillys for a science museum. Jade is then contacted by a "man in black" to investigate and take pictures of a creature presumed to be DomZ twins in an abandoned mine on a nearby island. The DomZ twins turns out to be the antennae of a huge DomZ monster. Once defeated, the "man in black" takes off his suit and a taxi car flies out of the limousine he was driving. The man reveals he actually works for the IRIS Network, and that the job was a test of Jade's skills.

Jade is then recruited as an agent of the network, which suspects that the Alpha Sections are behind planet-wide disappearances. Jade's first target of investigation is an Alpha Sections-run ration factory. She discovers evidence of human trafficking orchestrated by the DomZ under the Alpha Sections' authority. Along the way she rescues Double H, who was kidnapped and tortured by the DomZ. Pey'j is then abducted by the DomZ and taken to an abandoned slaughterhouse where he and the other kidnapped victims are to be transported to a base on Hillys' moon, Selene. After failing to extract Pey'j from the slaughterhouse in time, Jade learns that he was, in fact, the secret chief of the IRIS Network.

Jade learns that the Alpha Sections are being possessed and manipulated by the DomZ. Using Beluga, the ship Pey'j used to travel to Hillys, Jade and Double H go to the DomZ lunar base. There, Jade finds Pey'j dead after weeks of torture, but a strange power inside her brings back his soul, reviving him. After rescuing Pey'j, destroying Kehck's command ship, transmitting her final report, and sparking a revolution against the Alpha Sections, Jade confronts the DomZ High Priest. She learns that her human form is the latest container to hide a power stolen from the DomZ centuries ago in the hope that the High Priest, who must have spirit energy to survive, would starve to death. The High Priest managed to find a substitute energy in the souls of all those kidnapped from Hillys, and captures Pey'j and Double H to force Jade to submit to him. Using the stolen power within her, Jade is able to destroy the High Priest, though nearly losing control of her soul in the process, and then revives and rescues those that have been abducted. In a post-credits scene back on Hillys, a DomZ spore grows on Pey'j's hand as the screen fades to black.

Development

[edit]

Beyond Good & Evil was developed by Michel Ancel, the creator of the Rayman video game, at Ubisoft's Pictures studio in Montpellier.[16] The game was developed under the codename "Project BG&E", with production lasting more than three years.[17] A group of 30 employees composed the development team.[16] Ubisoft's chief executive officer, Yves Guillemot, fully supported the project and frequently met with the team.[18] After years working on Rayman, Ancel wanted to move on to something different.[18][19] He recalled that the goal of Beyond Good & Evil was to "pack a whole universe onto a single CD—mountains, planets, towns. The idea was to make the player feel like an explorer, with a sense of absolute freedom."[16]

A second goal behind Beyond Good & Evil's design was to create a meaningful story amid player freedom. Ancel said that the linear nature of the gameplay was necessary to convey the story; player freedom was an experience between parts of the plot.[19] He also strove to create a rhythm similar to a movie to engage and delight players.[20] The game drew on many influences and inspirations, including the Miyazaki universe, politics and the media, and the aftermath of the September 11 attacks.[21] In creating the lead character, Ancel's wife reportedly inspired the designer, who wanted to portray a persona with whom players could identify.[22]

Beyond Good & Evil was first shown publicly at the 2002 Electronic Entertainment Expo, where it received a negative reception.[18] Originally more "artistically ambitious" and resembling games like Ico, the game was substantially changed in order to make it more commercially appealing. Jade, originally a teenage girl, was redesigned to be more powerful and befitting of her job. The game was also shortened by removing long periods of exploration, due to Ancel's dislike of this aspect of gameplay in The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. The development team was "demoralized" by the changes, with Ancel commenting that the finished game resembled a sequel more than a reworking.[14] Prior to release, playable previews of the game were offered in movie theaters.[23]

Audio

[edit]The soundtrack of Beyond Good & Evil was composed by Christophe Héral, who was hired by Ancel because of his background in film. Hubert Chevillard, a director with whom Ancel had worked in the past, had also worked with Héral on a television special, The Pantin Pirouette, and referred him to Ancel. Héral was assisted by Laetitia Pansanel, who orchestrated the pieces, and his brother Patrice Héral, who performed some of the sound effects and singing.[24]

The soundtrack incorporates a wide variety of languages and instruments from around the world. Mainly Bulgarian lyrics were chosen for the song "Propaganda", which plays in the game's Akuda Bar,[25] to allude to the Soviet propaganda of the Cold War. It uses a recording of a telephone conversation by Héral with a female Bulgarian friend to represent the government's control of the media. It also incorporates Arabic string instruments and Indian percussion. A song called "Funky Mullah" was originally planned for the Akuda Bar, but it was replaced by "Propaganda" because Héral decided that its muezzin vocals, recorded on September 8, 2001, would have been in bad taste in the wake of the September 11 attacks. "Fun and Mini-games", a song that plays during hovercraft races and other minigames, includes Spanish lyrics. The lyrics for DomZ music were created from a fictional language with prominent rolling "r" sounds. The crashing metal sound effects of "Metal Gear DomZ", the music played during a boss fight, were recorded from the son of Héral's neighbor playing with scrap metal. The voices in the city of Hillys were also recorded by Héral himself.[24] The music had not been initially published as an album and instead had been released in its entirety as a free download by Ubisoft.[26] However, on June 26th, 2024, Ubisoft announced the release of the entire soundtrack on double vinyl through Wayô Records to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the game and the 2024 remaster.[27][28] The soundtrack is featured in the Video Games Live international concert tour.[29]

Release

[edit]Beyond Good & Evil was first released for PlayStation 2 in North America on November 11, 2003,[30] with versions for Microsoft Windows and Xbox following on December 2 of that same year.[31] The GameCube version, which was initially scheduled to ship alongside the latter platforms, was delayed until December 10.[32][33] The game was released in Europe for PlayStation 2 and Windows on November 14 and December 5, respectively.[34][35] The GameCube and Xbox versions were released the following year on February 27, 2004.[36]

Remasters

[edit]A full HD remastered version of the game was developed by Ubisoft Shanghai, released on Xbox Live Arcade on March 2, 2011, and on PlayStation Network in Europe on June 8, 2011, and in North America on June 28.[37][38][39][40] It features improved character models and textures, as well as a modified soundtrack. Achievements, trophies and online leaderboards were also added.[41] The HD edition was made backwards compatible on the Xbox One and available free to Gold members from August 16, 2016, through September 1, 2016, as part of the Games with Gold program. Ubisoft released Beyond Good & Evil HD for retail in Europe on September 21, 2012. The retail package includes Beyond Good & Evil HD, Outland and From Dust.[42]

An early version of another remaster, the 20th Anniversary Edition, was accidentally released to some Ubisoft+ subscribers on Xbox platforms by Ubisoft on November 29, 2023. It was quickly removed from availability. The official release date was set for early 2024, although it did not end up releasing at that timeframe.[43] The remaster's existence was leaked in August 2023.[44] It was officially unveiled on June 20, 2024, and released five days later.[45][46] In addition to updated graphics and remastered audio, 20th Anniversary Edition adds new features, including a speedrun mode; an anniversary gallery containing original development art, screenshots, and footage; unlockable cosmetic items for the main characters, weapons, and vehicles; and a new sidequest that connects to the story of Beyond Good & Evil 2.[47]

Reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | PS2: 86/100[48] PC: 83/100[49] XBOX: 87/100[50] GCN: 87/100[51] X360: 84/100[52] PS3: 83/100[53] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| GameSpot | 8.3/10[4][54][55][56] |

| GameSpy | |

| IGN | 9.0/10[6][61][62][63] (HD) 8.5/10[64] |

Prior to its release, Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine and PlayStation Magazine praised Beyond Good & Evil at E3 2003 and described it as one of the best titles on display.[20][65]

Beyond Good & Evil received "generally favorable" reviews from critics, according to review aggregator website Metacritic.[50][51][48][52][53][49]

The game's graphics were generally well received. In reviewing the GameCube version, Game Informer wrote that "Every moment of Beyond Good & Evil looks as good as a traditional RPG cutscene" and that the game's effects and character animations were "amazing".[66] On the other hand, Jon Hicks of PC Format wrote that while some effects were excellent, the game's otherwise unspectacular graphics were unwelcome reminders of the game's console roots.[67] 1UP.com and Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine cited glitches such as frame rate as irksome, because the game did not appear to tax the console's hardware.[68][69]

From this day forth, Michel Ancel is no longer 'the creator of Rayman'. From now on, he is 'the genius that brought us Beyond Good & Evil' [...] Cast out amongst a slew of Christmas blockbusters, BG&E rises above them all and leaves an indelible impression.

Edge commended the game for its storytelling and design, but criticized its plot as unable to "match Jade's initial appeal," becoming "fairly mundane" without "the darkness and moral ambiguity suggested by the title", with Jade's everyman appeal undermined by the revelation of her "mysterious hidden identity". Dan Toose of SMH called the game's setting "dark, baroque and earthy, a far cry from the squeaky-clean action of the Final Fantasy games," and described the game as "a very European take on the role-playing genre" and "one of the best adventure games in years".[71] Star Dingo of GamePro commented that the game was a "jack of all trades, master of none" that "never really lives up to its title", adding that its vision could have been more focused.[72] Among complaints were control issues and a lack of gameplay depth. Game Informer's Lisa Mason wrote that the game's controls were serviceable, but simplistic, and that she wished she could do more with the character.[73] PC Gamer's Kevin Rice found most of the gameplay and its exploration refreshing, but called hovercraft races "not much fun" and felt combat was the game's weakest element.[74] Edge called the gameplay interaction "hollowed out", as an unintended consequence of Ancel's attempt to streamline the game.[14]

Sales

[edit]Beyond Good & Evil was not a commercial success. The game saw poor sales upon its release in the 2003 Christmas and holiday season. Retailers quickly decreased the price by up to 80 percent. Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine staff attributed the poor sales of the game—among many other 2003 releases—to an over-saturated market, and labeled Beyond Good & Evil as a commercial "disappointment".[75] In retrospect, Ancel noted that consumers at the time were interested in established franchises and technologically impressive games. Coupled with the number of "big titles" available, he stated that the market was a poor environment for Beyond Good & Evil and that it would take time to be appreciated.[18] The Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine staff further commented that the lack of marketing from Ubisoft and the game's odd premise naturally reserved it to obscurity.[75] Part of the disappointing sales stemmed from Ubisoft not knowing how to market the title,[76] something that Ubisoft North America CEO Laurent Detoc labeled as one of his worst business decisions.[77] At the time, Ubisoft's marketing efforts were more focused on the release of Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time.[75] Ubisoft's former North American vice-president of publishing, Jay Cohen, and its European managing director, Alaine Corre, attributed the commercial failure of the game to a lack of marketing. "The game play was there, the technical excellence was there but perhaps the target audience was not there," Corre told the BBC.[78][79] Corre later commented that the Xbox 360 release (in 2011) "did extremely well", but considered this success "too late" to make a difference in the game's poor sales.[18] The game was intended to be the first part of a trilogy, but its poor sales placed those plans on hold at the time.[80]

Awards and legacy

[edit]Beyond Good & Evil was nominated for and won many gaming awards. The International Game Developers Association nominated the title for three honors at the 2004 Game Developers Choice Awards: "Game of the Year", "Original Game Character of the Year" (Jade) and "Excellence in Game Design".[81][82] Ubisoft titles garnered six of eleven awards at the 2004 IMAGINA Festival in France, with Beyond Good & Evil winning "Best Writer" and "Game of the Year Team Award".[83] In IGN's "The Best of 2003", the PlayStation 2 (PS2) version won "Best Adventure Game", while the GameCube version received "Best Story".[84][85] Beyond Good & Evil's audio was also recognized. The game was nominated for the "Audio of the Year", "Music of the Year", "Best Interactive Score", and "Best Sound Design" awards at the second annual Game Audio Network Guild awards.[86] During the 7th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards, the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences nominated the game for outstanding achievement in "Animation", "Character or Story Development", "Original Music Composition", and "Sound Design".[87] At the 3rd Annual National Academy of Video Game Trade Reviewers Awards, the game was nominated for the following categories: "Game Design"; "Original Adventure Game"; "Control Design", winning 2 ("Game Design" and "Original Adventure Game").

In 2007, Beyond Good & Evil was named 22nd-best Xbox game and 12th-best GameCube game of all time by IGN.[88][89] Game Informer listed the title 12th on its "Top 25 GameCube Games" list.[90] In another list, "Top 200 Games of all Time", Game Informer placed the PS2, Xbox, and GameCube versions of Beyond Good & Evil as the 200th best.[91] Official Nintendo Magazine ranked it as the 91st-best Nintendo game, while Nintendo Power ranked it 29th.[92][93] Nintendo Power placed the GameCube version as the 11th-best GameCube game of all time in its 20th anniversary issue.[94] Destructoid ranked the GameCube, PlayStation 2, and Xbox versions as the 6th-best game of the decade.[95] In 2010, IGN listed it at #34 in their "Top 100 PlayStation 2 Games".[96] GamesRadar placed it as the 70th best game of all time.[97]

Legacy

[edit]Sequel or prequel

[edit]Ancel stated his desire to produce a sequel to the game.[80] Ubisoft announced at the Ubidays 2008 opening conference that there would be a second game.[3][98] A sequel, tentatively titled Beyond Good and Evil 2, is currently in development,[3] although the project was temporarily halted to focus on Rayman Origins.[18] Michel Ancel has hinted that Jade would have a new look for the game.[99] In early 2016, Destructoid published a rumor that the game was being funded by Nintendo as an exclusive to their upcoming console codenamed "NX" (later officially unveiled as the Nintendo Switch).[100] On September 27, 2016, Michel Ancel posted an image to Instagram with the caption "Somewhere in system 4 ... - Thanks #ubisoft for making this possible !". On October 4, Ancel stated that Beyond Good and Evil 2 was in pre-production. Ubisoft confirmed Ancel's claim on October 6, 2016.[101] Ubisoft showed the first new trailer for Beyond Good and Evil 2 during their E3 2017 conference and was announced as a prequel to the first game.[102] During E3 2017, Ancel confirmed that the 2008 and 2009 trailers were from initial work as a narrative sequel to Beyond Good & Evil, but during development they opted to change direction and make it a prequel, and thus the work previously shown was from an effectively different game.[103] There had been rumors that it would have been released as a timed exclusive for the Nintendo Switch in the prior year,[104] but Ancel confirmed this was not the case. The "Space Monkey Program" lists the game for Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 4 and Xbox One, however Michel Ancel stated that the platforms have not been announced yet, and that the listing was due to a bug.[105][106] Ancel later told Kotaku that the game is designed to run on many platforms.[107]

When Ancel announced his departure from Ubisoft in September 2020, he stated that both the project and Wild were in capable hands.[108] The French newspaper Libération, which have been following on Ubisoft's troubles with mid-2020 series of sexual misconduct allegations raised against many high-level members of the company, learned that members of Ancel's team found Ancel's leadership on the project to be unorganized and at times abusive, causing the game's development to have many restarts and accounting for the delay since its 2010 announcement. The Montpellier team had reported these concerns to leadership of Ubisoft as early as 2017 but Ancel's close relationship with Yves Guillemot prevented any major corrections to occur until the 2020 internal evaluations that led to Ancel's departure.[109] Ubisoft stated that Ancel "hasn't been directly involved in BG&E2 for some time now" when he left the company.[110] In July 2021, Ubisoft stated in a financial report that development was "progressing well" but did not answer a question about its release date.[111] On February 9, 2022, Bloomberg News reported that the sequel "remains in pre-production after at least five years of development".[112] In 2022, the prequel broke the record held by Duke Nukem Forever (2011) for the longest development for a video game, at more than 15 years.[113]

Other media

[edit]In late July 2020, streaming service company Netflix announced a live-action animated film adaptation based on the video game is in development with Detective Pikachu director Rob Letterman.[114] No further updates have been given for the film since the announcement.

Jade and Pey'j appear as characters in the 2023 Netflix animated series Captain Laserhawk: A Blood Dragon Remix, voiced by Courtney Mae-Briggs and Glenn Wrage respectively. In the series, they are depicted as captive rebels and love interests who are recruited into a team led by the eponymous character.[115]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ @bgegame (June 24, 2024). "Ubisoft collaborated with Virtuos Games to develop the game, under the supervision of Ubisoft Montpellier 🤝" (Tweet). Retrieved 2024-06-24 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Why Beyond Good & Evil is one of the greatest games ever made". 29 August 2012. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ a b c "Connect: Going Beyond Good & Evil". Game Informer. No. 184. GameStop. August 2008. p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e Gerstmann, Jeff (November 25, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil Review (PC)". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on March 14, 2004. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ Beyond Good & Evil Instruction Manual (PC version). Ubisoft. 2003. pp. 7–8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-13. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ^ a b c d e Adams, David (November 11, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil — PC review at IGN". IGN. Ziff Davis. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 11, 2004. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ Beyond Good & Evil Instruction Manual (PC version). Ubisoft. 2003. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-13. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ^ Beyond Good & Evil Manual (Gamecube). Ubisoft. p. 16.

- ^ Beyond Good & Evil Manual (Gamecube). Ubisoft. p. 19.

- ^ "E3 2003: Beyond Good and Evil". IGN. Ziff Davis Media. May 14, 2003. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ^ Edge Staff (September 29, 2009). "Time Extend: Beyond Good & Evil". Edge Online. p. 2. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ Beyond Good & Evil Instruction Manual (PC version). Ubisoft. 2003. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-13. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ^ a b Torres, Ricardo (November 6, 2003). "Beyond Good and Evil Updated Preview". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ a b c Edge Staff (October 5, 2009). "Time Extend: Beyond Good & Evil". Edge Online. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ Nowak, Pete (2004-02-20). "Beyond Good & Evil". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ a b c IGN Staff (May 24, 2002). "E3 2002: Project BG&E Interview". IGN. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ Satterfield, Shane (May 23, 2002). "E3 2002: Project BG&E hands-on". GameSpot. CBS Interactive). Archived from the original on April 7, 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f Bertz, Matt (December 6, 2011). "Ubi Uncensored: The History Of Ubisoft By The People Who Wrote It". Game Informer. p. 5. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ^ a b Turner, Benjamin (September 17, 2003). "Michel Ancel: Beyond Rayman". GameSpy. Archived from the original on September 8, 2004. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ^ a b "Beyond Good & Evil Hands On". Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine. No. 71. Future Publishing. August 2003. p. 65.

- ^ Purchese, Robert (April 3, 2009). "BG&E2 inspired by September 11". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on January 30, 2015. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ^ Flower, Zoe (January 9, 2005). "Getting the Girl". 1UP.com. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ Totilo, Stephen (October 3, 2006). "GameFile: Peter Jackson's Mission; Big-Screen 'Gears Of War' And More". MTV.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "Christophe Héral Interview" (in French). Beyond Good & Evil Myth. Archived from the original on November 1, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "Game music of the day: Beyond Good & Evil". 18 December 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Beyond Good & Evil soundtrack". Snarfed.org. January 1, 2003. Archived from the original on March 19, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- ^ "Announcement of the Beyond Good & Evil soundtrack vinyl release on Ubisoft Music's X account". Ubisoft Music via Wayô Records. June 26, 2024. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ "Beyond Good & Evil soundtrack vinyl release on Wayô Records' website". Ubisoft Music via Wayô Records. June 26, 2024. Archived from the original on June 26, 2024. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ "Video Games Live". Video Games Live. Archived from the original on February 24, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ "Beyond Good & Evil ships for the PS2". GameSpot. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ "Beyond Good & Evil Now Available for Xbox and PC". Ubisoft. December 2, 2003. Archived from the original on April 7, 2004. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ I. G. N. Staff (2003-10-29). "BG&E GCN Delay". IGN. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ "Beyond Good & Evil". IGN. June 3, 2004. Archived from the original on June 3, 2004. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ "What's New?". Eurogamer.net. 2003-11-14. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ "What's New?". Eurogamer.net. 2003-12-05. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ "Eurogamer.net - Your daily slice of gaming". 2004-02-14. Archived from the original on 2004-02-14. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ Varanini, Giancarlo (September 30, 2010). "Beyond Good and Evil HD Hands-On". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on March 22, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (February 8, 2011). "Xbox Live Arcade's House Party Priced & Dated". Kotaku. Gawker Media. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ Makuch, Eddie (June 2, 2011). "Beyond Good & Evil HD hits PSN June 8". Gamespot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ "Beyond Good & Evil HD Hits US PSN June 28". Exophase. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ "Beyond Good & Evil HD Coming Next Year". IGN. Ziff Davis. September 30, 2010. Archived from the original on March 21, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ Matulef, Heffret (June 20, 2012). "Beyond Good & Evil HD, Outland and From Dust bundled for retail". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (29 November 2023). "People are now playing the still-unannounced Beyond Good & Evil 20th Anniversary Edition". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (31 August 2023). "Looks like there's a Beyond Good & Evil 20th Anniversary Edition". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Lyles, Taylor; Stedman, Alex (2024-06-20). "Beyond Good & Evil 20th Anniversary Edition Officially Unveiled at LRG3 2024". IGN. Retrieved 2024-06-20.

- ^ Hollister, Sean (2024-06-20). "Watch the trailer for Beyond Good & Evil 20th Anniversary Edition — coming June 25th". The Verge. Retrieved 2024-06-20.

- ^ Talbot, Ken (June 25, 2024). "Review: Beyond Good & Evil 20th Anniversary Edition (PS5)". Push Square. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "Beyond Good & Evil for PlayStation 2 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ a b "Beyond Good & Evil for PC Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on December 27, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ a b "Beyond Good & Evil for Xbox Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ a b "Beyond Good & Evil for GameCube Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on March 25, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ a b "Beyond Good & Evil HD for Xbox 360 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ a b "Beyond Good & Evil HD for PlayStation 3 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ Gerstmann, Jeff (November 13, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil Review (PS2)". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on February 18, 2004. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ Gerstmann, Jeff (November 13, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil Review (Xbox)". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on February 4, 2004. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ Gerstmann, Jeff (December 3, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil Review (GC)". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on January 14, 2004. Retrieved December 16, 2009.

- ^ Turner, Benjamin (December 19, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil (PS2)". GameSpy. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 4, 2004. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ Rausch, Allen (December 13, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil (PC)". GameSpy. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 4, 2004. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ Turner, Benjamin (December 19, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil (Xbox)". GameSpy. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 3, 2004. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ Turner, Benjamin (December 19, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil (GC)". GameSpy. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 3, 2004. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ Adams, David (November 11, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil — PlayStation 2 review at IGN". IGN. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 16, 2004. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Adams, David (November 11, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil — Xbox review at IGN". IGN. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 3, 2004. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Adams, David (November 11, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil — GameCube review at IGN". IGN. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 3, 2004. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Kolan, Patrick (March 2, 2011). "Beyond Good & Evil HD Review". IGN. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 26, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ "E3 2003". PlayStation Magazine. No. 74. Future Publishing. August 2003. p. 48.

- ^ "Beyond the Norm". Game Informer. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ^ Hicks, Jon (2004). "Beyond Good and Evil". PC Format. Archived from the original on February 6, 2008. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ Staff. "Beyond Good and Evil (PS2) Reviews; Beyond good gameplay, with some really evil glitches". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- ^ Steinman, Gary (November 4, 2003). "Beyond Good and Evil (PS2)". Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine. Archived from the original on December 31, 2003. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ Bramwell, Tom (November 23, 2003). "Beyond Good & Evil". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ Toose, Dan (December 6, 2003). "Die Hard". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- ^ Dingo, Star (November 12, 2003). "Beyond Good and Evil". GamePro. Archived from the original on December 2, 2009. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ Mason, Lisa. "Beyond Good and Evil". Game Informer. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ Rice, Kevin. "PC Gamer: Beyond Good & Evil". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on February 3, 2008. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Spin: Bad Timing". Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine. No. 78. Ziff Davis. March 2004. pp. 30–31.

- ^ IGN AU Staff (February 19, 2009). "Beyond Good & Evil 2: What to Expect". IGN. Ziff Davis. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ Detoc, Laurent (August 23, 2005). "Executive Profile". San Francisco Business Times. Archived from the original on November 20, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- ^ Feldman, Curt (May 11, 2004). "Q&A: Ubisoft's Jay Cohen". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on October 20, 2007. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ Waters, Darren (June 14, 2004). "Game firms urged to take risks". BBC. Archived from the original on November 15, 2005. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- ^ a b Bramwell, Tom (August 23, 2005). "It would be 'good to finish' BG&E — Michel Ancel". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ Jenkins, David (February 25, 2004). "IGDA Announces Nomineses; More Award Winners". Gamasutra. UBM TechWeb. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ^ Viscel, Mike (February 25, 2004). "Nominees for Game Developers Choice Awards". GameDaily. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- ^ "Ubisoft Rewarded For Their Creativity At The Imagina Festival". GameZone. February 11, 2004. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- ^ IGN Staff. "IGN.com presents The Best of 2003 - Best Adventure Game (PS2)". IGN. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved 2010-12-20.

- ^ IGN Staff. "IGN.com presents The Best of 2003 - Best Story (GC)". IGN. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved 2010-12-20.

- ^ "Game Audio Network Guild Announces 2nd Annual G.A.N.G Awards/Nominees". Music4Games. Archived from the original on 2005-12-17. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ^ "D.I.C.E. Awards By Video Game Details Beyond Good & Evil". interactive.org. Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ^ Perry, Douglass C.; Brudvig, Erik; Miller, Jonathan (March 16, 2007). "The Top 25 Xbox Games of All Time". IGN. Ziff Davis. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 15, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- ^ IGN GameCube Team (March 16, 2007). "The Top 25 GameCube Games of All Time". IGN. Ziff Davis. p. 3. Archived from the original on March 25, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- ^ "Classic GI: Top 25 GameCube Games". Game Informer. No. 189. GameStop. January 2009. p. 85.

- ^ Game Informer Staff (2009). "The Top 200 Games of all Time". Game Informer. No. 200. p. 79.

- ^ "100 Best Nintendo Games: Part One". Future Publishing. February 17, 2009. Archived from the original on February 23, 2009. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ Nintendo Power Staff (February 2006). "NP Top 200". Nintendo Power. No. 200. Future Publishing. p. 60.

- ^ Nintendo Power Staff (August 2008). "Best of the Best". Nintendo Power. No. 231. p. 76.

- ^ Concelmo, Chad (December 4, 2009). "The Top 50 Videogames of the Decade (#10-1)". Destructoid. Archived from the original on November 28, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ "Top 100 PlayStation 2 Games". IGN. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- ^ GamesRadar US & UK (March 31, 2011). "The 100 best games of all time". Future Publishing. p. 4. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ Ransom-Wiley, James (May 28, 2008). "Beyond Good & Evil 2 revealed at Ubidays 2008". Joystiq. Archived from the original on May 29, 2008. Retrieved January 10, 2007.

- ^ Hindes, Daniel (April 14, 2014). "Beyond Good and Evil 2 director teases new look for Jade". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- ^ "Rumor: Nintendo funding Beyond Good and Evil sequel". March 3, 2016. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ Matulef, Jeffrey (2016-10-06). "Beyond Good & Evil 2 is almost definitely in development". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on 2016-10-13. Retrieved 2016-10-13.

- ^ Hussain, Tamoor; Knezevic, Kevin (12 June 2017). "E3 2017: Beyond Good & Evil 2 Trailer Finally Shown". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (14 June 2017). "Beyond Good & Evil 2 is wildly ambitious, but it's still at 'day zero' of development". The Verge. Vox Media. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Kate Date, Laura (3 March 2016). "Rumor: Nintendo funding Beyond Good and Evil sequel". Destructoid. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ Arif, Shabana (14 June 2017). "Beyond Good and Evil 2 Switch timed-exclusive rumors squashed, platforms confirmed by Space Monkey Program". VG247. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Sickr (14 June 2017). "Michel Ancel: Platforms For Beyond Good & Evil 2 Haven't Been Announced And Survey A Bit Buggy". My Nintendo News. Excite Global Media. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Totilo, Stephen (14 June 2017). "What Beyond Good & Evil 2 Is Now, And What Its Creators Dream It Can Be". Kotaku. Gizmodo Media Group. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (September 18, 2020). "Rayman creator Michel Ancel quits video games to work on wildlife sanctuary". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ Olson, Mathew (September 25, 2020). "Report: Michel Ancel Accused of Abusive, Disruptive Practices on Beyond Good & Evil 2". USGamer. Archived from the original on November 21, 2020. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- ^ Chalk, Andy (18 September 2020). "Beyond Good & Evil creator Michel Ancel quits videogames to work in an animal sanctuary". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on 11 June 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Gerblick, Jordan (20 July 2021). "Ubisoft confirms Beyond Good & Evil 2 is still in development". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Schreier, Jason (2022-02-09). "Ubisoft Plans New Assassin's Creed Game to Help Fill Its Schedule". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 2022-03-01. Retrieved 2022-03-01.

- ^ Wolens, Joshua (October 3, 2022). "Beyond Good and Evil 2 has broken Duke Nukem Forever's record for longest game development time". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved October 4, 2022.

- ^ "'Detective Pikachu' Director and Netflix Tackling 'Beyond Good & Evil' Adaptation (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. 31 July 2020. Archived from the original on 30 March 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ Bankhurst, Adam (September 27, 2023). "Captain Laserhawk: A Blood Dragon Remix Gets Official Release Date, New Cast Members". IGN. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

External links

[edit]- 2003 video games

- Action-adventure games

- Jade (game engine) games

- GameCube games

- Open-world video games

- PlayStation 2 games

- PlayStation Network games

- Science fiction video games

- Stealth video games

- Ubisoft games

- Video games developed in France

- Video games developed in Italy

- Video games directed by Michel Ancel

- Video games featuring female protagonists

- Video games scored by Christophe Héral

- Video games set in the 25th century

- Video games set on fictional islands

- Video games set on fictional planets

- Windows games

- Xbox games

- Xbox 360 Live Arcade games

- Single-player video games