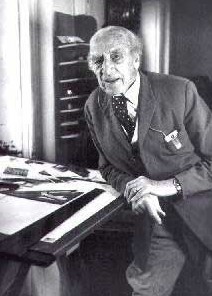

Clough Williams-Ellis

Sir Clough Williams-Ellis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 28 May 1883 Gayton, Northamptonshire, England |

| Died | 9 April 1978 (aged 94) |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Projects | Creator of the Italianate village of Portmeirion in North Wales |

Sir Bertram Clough Williams-Ellis, CBE, MC (28 May 1883 – 9 April 1978) was a Welsh architect known chiefly as the creator of the Italianate village of Portmeirion in North Wales. He became a major figure in the development of Welsh architecture in the first half of the 20th century, in a variety of styles and building types.[1]

Early life

[edit]

Clough Williams-Ellis was born in Gayton, Northamptonshire, England, but his family moved back to his father's native North Wales when he was four. The family have strong Welsh roots and Clough Williams-Ellis claimed direct descent from Owain Gwynedd, Prince of North Wales.[2] His father John Clough Williams Ellis (1833–1913) was a clergyman and noted mountaineer while his mother Ellen Mabel Greaves (1851–1941) was the daughter of the slate mine proprietor John Whitehead Greaves and sister of John Ernest Greaves.[3]

He was educated at Oundle School in Northamptonshire. Though he read for the natural sciences tripos at Trinity College, Cambridge, he never graduated. After a few months at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London in 1903–04 (which he located by looking up "Architecture" in the London telephone directory), he worked for an architect for a few months before setting up his own practice in London. His first commission was Larkbeare, a summer house for Anne Wynne Thackeray in Cumnor, Oxfordshire, in 1903-04 (finished 1907) which he designed while still a student.

In 1908 he inherited a small country house, Plas Brondanw, from his father, which he would restore and embellish through the rest of his life, as well as rebuilding it after a fire in 1951.

Military service

[edit]Williams-Ellis served with distinction in the First World War, first with the Royal Fusiliers and then with the Welsh Guards as an intelligence officer attached to the Tank Corps. He was described as lieutenant on the day of his wedding.[4]

Architectural career

[edit]

After the war, Williams-Ellis helped John St Loe Strachey (later his father-in-law) revive pisé construction in Britain,[5] building an apple storehouse followed by Harrowhill Copse bungalow at Newlands Corner using shuttering and rammed earth.[6]

One of his earliest designs of 1905 was for a pair of Welsh labourers' cottages in a vernacular style with end gable chimneys which imitate the 16th-century Snowdonia Houses[7] In 1909 he designed a house in an advanced Arts and Crafts style for Cyril Joynson at Brecfa in Breconshire[7] In 1913–1914 he was responsible for the rebuilding of Llangoed Hall in Breconshire, one of the last country houses to be built before the First World War. While it is a mixture of a number of historic styles, it also has modern features with elements such as the chimneys derived from the work of Lutyens.[8] Other work in Wales by Clough Williams-Ellis includes the Festiniog Memorial Hospital of 1922, Pentrefelin Village Hall, and the Conway Fall Cafe.[9]

In 1925, Williams-Ellis acquired the land in North Wales that would become the Italianate village of Portmeirion[10] (made famous in the 1960s as the location of the cult TV series The Prisoner, and the 1976 Doctor Who story The Masque of Mandragora). Portmeirion is notable not only as an architectural composition, but also because Clough Williams-Ellis was able to preserve fragments from other now demolished buildings from Wales and Cheshire. These include the plaster ceiling from Emral Hall[11]

In 1928, Williams-Ellis wrote his book England and the Octopus (published in 1928); its outcry at the urbanization of the countryside and loss of village cohesion inspired a group of young women to form Ferguson's Gang. They took up Williams-Ellis's call for action and from 1927 to 1946 were active in rescuing important, but lesser-known, rural properties from being demolished. Shalford Mill in Surrey, Newtown Old Town Hall on the Isle of Wight and Priory Cottages in Oxfordshire were all successfully saved due to the Gang's fundraising efforts. The Gang endowed these properties and significant tracts of the Cornish coastline to the care of the National Trust. The Gang's mastermind Peggy Pollard (known within the Gang by her pseudonym Bill Stickers) and Williams-Ellis became lifelong friends.[12]

In 1929 Williams-Ellis bought portrait painter George Romney's house in Hampstead.[13]

By the 1930s, Williams-Ellis had become a fashionable British architect; he was commissioned to create numerous works throughout the UK. These include buildings at Stowe, Buckinghamshire, cottages in Cornwell, Oxfordshire, Tattenhall in Cheshire, and Cushendun, County Antrim, Northern Ireland. During the 1930s he also designed the former summit building on Wales' highest mountain, Snowdon. However, after a reduction in window sizes (they kept blowing in) and further alterations in the 1960s and the 1980s, it was in a poor state by the end of the 20th century. Prince Charles described it as "the highest slum in Wales".[14]

Williams-Ellis served on several government committees concerned with design and conservation and was instrumental in setting up the British national parks after 1945. The following year he was appointed inaugural chairman of the Stevenage Development Corporation by Lewis Silkin. He wrote and broadcast extensively on architecture, design and the preservation of the rural landscape. He was a member of the Knickerbocker Club.[15]

At Aberdaron he designed the Old Post Office in a vernacular style in 1950.[9] An important later commission was the redesign and rebuilding of Nantclwyd Hall in Denbighshire Clough Williams- Ellis was equally capable in working in the Modernist idiom of the interwar years. This is well demonstrated by the recently restored Caffi Moranedd at Cricieth and the former Snowdon Summit Station of 1934, which was demolished in 2007.[16]

In 1958 Williams-Ellis was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) "for public services".[17] He was made a Knight Bachelor in the New Years Honours List of 1972 "for services to the preservation of the environment and to architecture".[18] At the time, he was the oldest person ever to be knighted.[19]

Work in Ireland

[edit]

- Seven two-storey houses at Cushendun, County Antrim for Ronald McNeill, 1912.

- Hall and Club, Cushendun, County Antrim for Ronald Mcneill, 1912 (Project).

- Glenmona Lodge, Cushendun, Co. antrim for Ronald McNeill, 1913.

- Lord MacNaghten Memoriual Hall and School at Giants Causeway, 1915.

- Glenmona House, Cushendun, County Antrim for Ronald Mcneill, 1923.

- First Church of Christ Scientist, University Avenue, Belfast 1923-37. (school 1923) (House 1928) Church 1936-7).

- Bushmills School for Sir Francis Alexander Macnaghten 1925-7.

- Maud Cottages, Cushendun, County Antrim for Ronald McNeill 1st Baron Cushendun 1926.

- Cushendun shop for A. McAlister, 1932. [20]

Personal life

[edit]In 1915 Williams-Ellis married the writer Amabel Strachey. Their eldest daughter, Susan Williams-Ellis (1918–2007), used the name Portmeirion Pottery for the company she created with her husband in 1961. The second daughter, Charlotte Rachel Anwyl Williams-Ellis (1919–2010), was a zoologist and environmentalist with a Cambridge PhD in agricultural science. She married the agriculturalist Lindsay Russell Wallace in 1945, and moved to New Zealand.[21][22] Their youngest child, Christopher Moelwyn Strachey Williams-Ellis (1923 – 13 March 1944) served as a lieutenant in the Welsh Guards during the Second World War. He was killed in action and is buried at Minturno War Cemetery.[23]

Welsh language novelist Robin Llywelyn is his grandson, and fashion designer Rose Fulbright-Vickers is his great-granddaughter.[24] Sculptor David Williams-Ellis, the stepfather of Edoardo Mapelli Mozzi, is his great-nephew.[25]

Death

[edit]Sir Clough Williams-Ellis died in April 1978, aged 94. In accordance with his wishes, he was cremated. Twenty years after his death some of his ashes were placed in a marine rocket that was launched in a New Year's Eve firework display over the estuary at Portmeirion.[26]

Works

[edit]Architecture

[edit]Writings

[edit]- Reconography (by student in BEF, pseudodonym Graphite) Pelman (1919 and 4 editions)

- England and the Octopus, London, Geoffrey Bles (1928)

- Cottage Building in Cob, Pise, Chalk and Clay: a Renaissance (1919)

- The Architect, London, Geoffrey Bles (1929)

- Cautionary Guide to Oxford, Design and Industrial Association (1930), 32 pages

- Cautionary Guide to St Albans, Design and Industrial Association (1930) 32 pages

- Laurence Weaver – a Biography, London, Geoffrey Bles (1933)

- Architecture Here and Now, London, T Nelson and Sons (1934)

- The Adventure of Building: being something about architecture and planning for intelligent young citizens and their backward elders, London, Architectural Press (1946), 91 pages

- An Artist in North Wales, London, Elek (1946), pictures by Fred Uhlman, 40 pages

- On Trust for the Nation (2 vols), London, Elek (1947), pictures by Barbara Jones, 168 pages

- Living in New Towns, London (1947)

- Town and Country Planning, Longmans, Green, London and British Council (1951), 48 pages

- Portmeirion, The Place and its Meaning, London (1963, revised edition 1973)

- Roads in the Landscape, Ministry of Transport (1967), 22 pages

- Architect Errant: The Autobiography of Clough Williams Ellis, London, Constable (1971), 251 pages

- Around the World in Ninety Years, Portmeirion (1978)

- With others

- Clough & Amabel Williams-Ellis, The Tank Corps (A War History), London (1919)

- ____ The Pleasures of Architecture London, Jonathan Cape (1924)

- ____ and Introduction by Richard Hughes, Headlong Down the Years, Liverpool University Press (1951), 118 pages

- Susan, Charlotte, Amabel and Clough Williams-Ellis, In and Out of Doors, London, Geo Routledge and Sons (1937), 491 pages

- With John Maynard Keynes, Britain and the Beast, London, Dent (1937), 332 pages

- With John Strachey, Architecture (1920, reprinted 2009), 125 pages

- With Sir John Summerson, Architecture Here and Now

Sources

[edit]- Haslam, R. (1996), Clough Williams-Ellis, RIBA Drawings Monograph No2. ISBN 1854904302

- Haslam R. et al. (2009), The Buildings of Wales: Gwynedd, Yale University Press.

- Scourfield R. and Haslam R. (2013), The Buildings of Wales: Powys; Montgomeryshire, Radnorshire and Breconshire, Yale University Press.

References

[edit]- ^ For an overview of Clough Williams-Ellis see Haslam (1996)

- ^ "Clough Williams-Ellis family tree (Glasfryn) : Portmeirion – Welcome to the official Portmeirion village web site". Archived from the original on 8 June 2011.

- ^ Bowen Rees, Ioan. "Williams-Ellis, John Clough (1833 - 1913)". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales.

- ^ Daily News, 2 Aug 1915

- ^ "Pisé" (PDF). www.arct.cam.ac.uk. 2 May 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ "Newlands Corner". www.alburyhistory.org.uk. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ a b Haslam (1996), p. 24, pl 1.

- ^ Scourfield

- ^ a b Haslam et al. (2009), p. 228

- ^ "The Story of Portmeirion". Portmeirion Cymru. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ Haslam et al. (2009), p. 685

- ^ Polly Bagnall & Sally Beck (2015). Ferguson's Gang: The Remarkable Story of the National Trust Gangsters. Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-1-909-88171-6.

- ^ Historic England. "Romneys House (1379069)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ "No cash for 'highest slum'". BBC News. 9 February 2001.

- ^ Around the World in Ninety Years, Pg. 80, Portmeirion (1978)

- ^ Haslam et al. (2009), pp. 394–5.

- ^ "Supplement to the London Gazette". The London Gazette. 31 December 1957.

- ^ "Supplement to the London Gazette". The London Gazette. 31 December 1971.

- ^ "Chronology : Portmeirion – Welcome to the official Portmeirion village web site". Archived from the original on 12 July 2011.

- ^ die.ie/architects/view/1780/Williams-Ellis

- ^ "Wallace, Charlotte Rachel Anwyl, 1919–2010". Wallace, Charlotte Rachel Anwyl, 1919... Items, National Library of New Zealand. 1 January 1919.

- ^ "Overseas Marriage". The New Zealand Herald. 9 May 1945. p. 4.

- ^ "Casualty". Retrieved 23 June 2021.

plot VIII, row C, grave 24

- ^ Victoria Moss (4 April 2015). "Rose Fulbright's deep influences". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015.

- ^ "Sculptor David Williams-Ellis on studying in Italy and why he never eats in restaurants". The Daily Telegraph. 28 November 2014.

- ^ "Rush to say 'I do' in Portmeirion". www.walesonline.co.uk. 24 March 2003.

External links

[edit]- 1883 births

- 1978 deaths

- 20th-century Welsh architects

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Architects from Northamptonshire

- British Army personnel of World War I

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Knights Bachelor

- Military personnel from Northamptonshire

- People educated at Oundle School

- People from Gayton, Northamptonshire

- Recipients of the Military Cross

- Royal Fusiliers officers

- Welsh Guards officers