Berne Convention

| Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works | |

|---|---|

Map of parties to the Convention | |

| Signed | 9 September 1886 |

| Location | Bern, Switzerland |

| Effective | 5 December 1887 |

| Condition | 3 months after exchange of ratifications |

| Parties | 181 |

| Depositary | Director General of the World Intellectual Property Organization |

| Languages | French (prevailing in case of differences in interpretation) and English, officially translated in Arabic, German, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish |

| Full text | |

The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, usually known as the Berne Convention, was an international assembly held in 1886 in the Swiss city of Bern by ten European countries with the goal of agreeing on a set of legal principles for the protection of original work. They drafted and adopted a multi-party contract containing agreements for a uniform, border-crossing system that became known under the same name. Its rules have been updated many times since then.[1][2] The treaty provides authors, musicians, poets, painters, and other creators with the means to control how their works are used, by whom, and on what terms.[3] In some jurisdictions these type of rights are referred to as copyright; on the European continent they are generally referred to as authors' rights (from French: droits d'auteur) or makerright (German: Urheberrecht).

As of November 2022, the Berne Convention has been ratified by 181 states out of 195 countries in the world, most of which are also parties to the Paris Act of 1971.[4][5]

The Berne Convention introduced the concept that protection exists the moment a work is "fixed", that is, written or recorded on some physical medium, and its author is automatically entitled to all copyrights in the work and to any derivative works, unless and until the author explicitly disclaims them or until the copyright expires. A creator need not register or "apply for" a copyright in countries adhering to the convention. It also enforces a requirement that countries recognize rights held by the citizens of all other parties to the convention. Foreign authors are given the same rights and privileges to copyrighted material as domestic authors in any country that ratified the convention. The countries to which the convention applies created a Union for the protection of the rights of authors in their literary and artistic works, known as the Berne Union.

Content

[edit]The Berne Convention requires its parties to recognize the protection of works of authors from other parties to the convention at least as well as those of its own nationals. For example, French authors' rights law applies to anything published, distributed, performed, or in any other way accessible in France, regardless of where it was originally created, if the country of origin of that work is in the Berne Union.

In addition to establishing a system of equal treatment that harmonised copyright amongst parties, the agreement also required member states to provide strong minimum standards for copyright law.

Author's rights under the Berne Convention must be automatic; it is prohibited to require formal registration. However, when the United States joined the convention on 1 March 1989,[6] it continued to make statutory damages and attorney's fees only available for registered works.

However, Moberg v Leygues (a 2009 decision of a Delaware Federal District Court) held that the protections of the Berne Convention are supposed to essentially be "frictionless", meaning no registration requirements can be imposed on a work from a different Berne member country. This means Berne member countries can require works originating in their own country to be registered and/or deposited, but cannot require these formalities of works from other Berne member countries.[7]

Applicability

[edit]Under Article 3, the protection of the Convention applies to nationals and residents of countries that are party to the convention, and to works first published or simultaneously published (under Article 3(4), "simultaneously" is defined as "within 30 days")[8] in a country that is party to the convention.[8] Under Article 4, it also applies to cinematic works by persons who have their headquarters or habitual residence in a party country, and to architectural works situated in a party country.[9]

Country of origin

[edit]The Convention relies on the concept of "country of origin". Often determining the country of origin is straightforward: when a work is published in a party country and nowhere else, this is the country of origin. However, under Article 5(4), when a work is published "simultaneously" ("within 30 days")[8] in several party countries,[8] the country with the shortest term of protection is defined as the country of origin.[10]

For works simultaneously published in a party country and one or more non-parties, the party country is the country of origin. For unpublished works or works first published in a non-party country (without publication within 30 days in a party country), the author's nationality usually provides the country of origin, if a national of a party country. (There are exceptions for cinematic and architectural works.)[10]

In the Internet age, unrestricted publication online may be considered publication in every sufficiently internet-connected jurisdiction in the world. It is not clear what this may mean for determining "country of origin". In Kernel v. Mosley (2011), a U.S. court "concluded that a work created outside of the United States, uploaded in Australia and owned by a company registered in Finland was nonetheless a U.S. work by virtue of its being published online". However other U.S. courts in similar situations have reached different conclusions, e.g. Håkan Moberg v. 33T LLC (2009).[11] The matter of determining the country of origin for digital publication remains a topic of controversy among law academics as well.[12]

Term of protection

[edit]The Berne Convention states that all works except photographic and cinematographic shall be protected for at least 50 years after the author's death, but parties are free to provide longer terms,[13] as the European Union did with the 1993 Directive on harmonising the term of copyright protection. For photography, the Berne Convention sets a minimum term of 25 years from the year the photograph was created, and for cinematography the minimum is 50 years after first showing, or 50 years after creation if it has not been shown within 50 years after the creation. Countries under the older revisions of the treaty may choose to provide their own protection terms, and certain types of works (such as phonorecords and motion pictures) may be provided shorter terms.[citation needed]

If the author is unknown because for example the author was deliberately anonymous or worked under a pseudonym, the Convention provides for a term of 50 years after publication ("after the work has been lawfully made available to the public"). However, if the identity of the author becomes known, the copyright term for known authors (50 years after death) applies.[13]

Although the Berne Convention states that the legislation of the country where protective rights are claimed shall be applied, Article 7(8) states that "unless the legislation of that country otherwise provides, the term shall not exceed the term fixed in the country of origin of the work",[13] i.e., an author is normally not entitled a longer protection abroad than at home, even if the laws abroad give a longer term. This is commonly known as "the rule of the shorter term". Not all countries have accepted this rule.

Minimum standards

[edit]As to works, protection must include "every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, whatever the mode or form of its expression" (Article 2(1) of the convention).

Subject to certain allowed reservations, limitations or exceptions, the following are among the rights that must be recognized as exclusive rights of authorization:

- the right to translate,

- the right to make adaptations and arrangements of the work,

- the right to perform in public dramatic, dramatico-musical and musical works,

- the right to recite literary works in public,

- the right to communicate to the public the performance of such works,

- the right to broadcast (with the possibility that a Contracting State may provide for a mere right to equitable remuneration instead of a right of authorization),

- the right to make reproductions in any manner or form (with the possibility that a Contracting State may permit, in certain special cases, reproduction without authorization, provided that the reproduction does not conflict with the normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author; and the possibility that a Contracting State may provide, in the case of sound recordings of musical works, for a right to equitable remuneration),

- the right to use the work as a basis for an audiovisual work, and the right to reproduce, distribute, perform in public or communicate to the public that audiovisual work.

Exceptions and limitations

[edit]The Berne Convention includes a number of specific exceptions, scattered in several provisions due to the historical reason of Berne negotiations.[citation needed] For example, Article 10(2) permits Berne members to provide for a "teaching exception" within their copyright statutes. The exception is limited to a use for illustration of the subject matter taught and it must be related to teaching activities.[14]

In addition to specific exceptions, the Berne Convention establishes the "three-step test" in Article 9(2), which establishes a framework for member nations to develop their own national exceptions. The three-step test establishes three requirements: that the legislation be limited to certain (1) special cases; (2) that the exception does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work, and (3) that the exception does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author.

The Berne Convention does not expressly reference doctrines such as fair use or fair dealing, leading some critics of fair use to argue that fair use violates the Berne Convention.[15][16] However, the United States and other fair use nations argue that flexible standards such as fair use include the factors of the three-step test, and are therefore compliant. The WTO Panel has ruled that the standards are not incompatible.[17]

The Berne Convention does not include the modern concept of Internet safe harbors, simply because Internet was not known as a technology at that time. The Agreed Statement of the parties to the WIPO Copyright Treaty of 1996 states that: "It is understood that the mere provision of physical facilities for enabling or making a communication does not in itself amount to communication within the meaning of this Treaty or the Berne Convention."[18] This language may mean that Internet service providers are not liable for the infringing communications of their users.[18]

Since companies are using internet to publish user generated content, critics have argued that the Berne Convention is weak in protecting users and consumers from overbroad or harsh infringement claims, with virtually no other exceptions or limitations.[19] In fact, the Marrakesh Copyright Exceptions Treaty for the Blind and Print-Disabled was the first international treaty centered around the rights of users. Treaties featuring exceptions for libraries and educational institutions are also being discussed.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

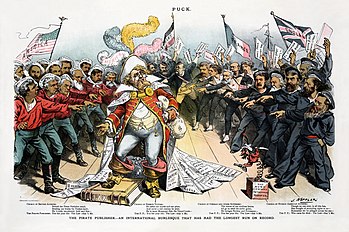

The Berne Convention was developed at the instigation of Victor Hugo[20] of the Association Littéraire et Artistique Internationale.[21] Thus it was influenced by the French "rights of the author" (droits d'auteur), which contrasts with the Anglo-Saxon concept of "copyright" which only dealt with economic concerns.[22]

Before the Berne Convention, copyright legislation remained uncoordinated at an international level.[23] So for example a work published in the United Kingdom by a British national would be covered by copyright there but could be copied and sold by anyone in France. Dutch publisher Albertus Willem Sijthoff, who rose to prominence in the trade of translated books, wrote to Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands in 1899 in opposition to the convention over concerns that its international restrictions would stifle the Dutch print industry.[24]

The Berne Convention followed in the footsteps of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property of 1883, which in the same way had created a framework for international integration of the other types of intellectual property: patents, trademarks and industrial designs.[25]

Like the Paris Convention, the Berne Convention set up a bureau to handle administrative tasks. In 1893 these two small bureaux merged and became the United International Bureaux for the Protection of Intellectual Property (best known by its French acronym BIRPI), situated in Berne.[26] In 1960, BIRPI moved to Geneva, to be closer to the United Nations and other international organizations in that city.[27] In 1967 it became the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), and in 1974 became an organization within the United Nations.[26]

The Berne Convention was completed in Paris in 1886, revised in Berlin in 1908, completed in Berne in 1914, revised in Rome in 1928, in Brussels in 1948, in Stockholm in 1967 and in Paris in 1971, and was amended in 1979.[28]

The World Intellectual Property Organization Copyright Treaty was adopted in 1996 to address the issues raised by information technology and the Internet, which were not addressed by the Berne Convention.[29]

Adoption and implementation

[edit]The first version of the Berne Convention treaty was signed on 9 September 1886, by Belgium, France, Germany, Haiti, Italy, Liberia, Spain, Switzerland, Tunisia, and the United Kingdom.[30] They ratified it on 5 September 1887.[31]

Although Britain ratified the convention in 1887, it did not implement large parts of it until 100 years later with the passage of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The United States acceded to the convention on 16 November 1988, and the convention entered into force for the United States on 1 March 1989.[32][31] The United States initially refused to become a party to the convention, since that would have required major changes in its copyright law, particularly with regard to moral rights, removal of the general requirement for registration of copyright works and elimination of mandatory copyright notice. This led first to the U.S. ratifying the Buenos Aires Convention (BAC) in 1910, and later the Universal Copyright Convention (UCC) in 1952 to accommodate the wishes of other countries. With the WIPO's Berne revision on Paris 1971,[33] many other countries joined the treaty, as expressed by Brazil federal law of 1975.[34]

On 1 March 1989, the U.S. Berne Convention Implementation Act of 1988 was enacted, and the U.S. Senate advised and consented to ratification of the treaty, making the United States a party to the Berne Convention,[35] and making the Universal Copyright Convention nearly obsolete.[36] Except for extremely technical points not relevant, with the accession of Nicaragua in 2000, every nation that is a member of the Buenos Aires Convention is also a member of Berne, and so the BAC has also become nearly obsolete and is essentially deprecated as well.

Since almost all nations are members of the World Trade Organization, the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) requires non-members to accept almost all of the conditions of the Berne Convention.

As of October 2022, there are 181 states that are parties to the Berne Convention. This includes 178 UN member states plus the Cook Islands, the Holy See and Niue.

Prospects for future reform

[edit]The Berne Convention was intended to be revised regularly in order to keep pace with social and technological developments. It was revised seven times between its first iteration (in 1886) and 1971, but has seen no substantive revision since then.[37] That means its rules were decided before widespread adoption of digital technologies and the internet. In large part, this lengthy drought between revisions comes about because the Treaty gives each member state the right to veto any substantive change. The vast number of signatory countries, plus their very different development levels, makes it exceptionally difficult to update the convention to better reflect the realities of the digital world.[38] In 2018, Professor Sam Ricketson argued that anyone who thought that further revision would ever be realistic was "dreaming".[39]

Berne members also cannot easily create new copyright treaties to address the digital world's realities, because the Berne Convention also prohibits treaties that are inconsistent with its precepts.[40]

Legal academic Rebecca Giblin has argued that one reform avenue left to Berne members is to "take the front door out". The Berne Convention only requires member states to obey its rules for works published in other member states – not works published within its own borders. Thus member nations may lawfully introduce domestic copyright laws that have elements prohibited by Berne (such as registration formalities), so long as they only apply to their own authors. Giblin also argues that these should only be considered where the net benefit would be to benefit authors.[41]

List of countries and regions that are not signatories to the Berne Convention

[edit] Angola (but joined TRIPS Agreement)

Angola (but joined TRIPS Agreement) Eritrea

Eritrea Ethiopia (but joined TRIPS Agreement as observer)

Ethiopia (but joined TRIPS Agreement as observer) Iran (but joined TRIPS Agreement as observer)

Iran (but joined TRIPS Agreement as observer) Iraq (but joined TRIPS Agreement as observer)

Iraq (but joined TRIPS Agreement as observer) Kosovo

Kosovo Maldives (but joined TRIPS Agreement)

Maldives (but joined TRIPS Agreement) Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands Myanmar (but joined TRIPS Agreement)

Myanmar (but joined TRIPS Agreement) Palau

Palau Palestine

Palestine Papua New Guinea (but joined TRIPS Agreement)

Papua New Guinea (but joined TRIPS Agreement) Seychelles (but joined TRIPS Agreement)

Seychelles (but joined TRIPS Agreement) Sierra Leone (but joined TRIPS Agreement)

Sierra Leone (but joined TRIPS Agreement) Somalia (but joined TRIPS Agreement as observer)

Somalia (but joined TRIPS Agreement as observer) South Sudan (but joined TRIPS Agreement as observer)

South Sudan (but joined TRIPS Agreement as observer) Taiwan (but joined TRIPS Agreement as

Taiwan (but joined TRIPS Agreement as  Chinese Taipei)

Chinese Taipei) Timor-Leste (but joined Universal Copyright Convention (Paris) as observer)

Timor-Leste (but joined Universal Copyright Convention (Paris) as observer)

See also

[edit]- Berne Convention Implementation Act of 1988

- Berne three-step test

- Buenos Aires Convention

- Droit de suite

- List of parties to international copyright agreements

- Copyright of official texts

- Post-colonial copyright crisis

- Public domain

- Rome Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organisations

- Universal Copyright Convention

- World Trade Organization Dispute 160

References

[edit]- ^ "WIPO - Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works".

- ^ WEX Definitions Team. "Berne Convention". Cornell Law School.

- ^ "Summary of the Berne Convention". World Intellectual Property Organization.

- ^ "WIPO Lex". wipolex.wipo.int. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, Status October 1, 2020 (PDF). World Intellectual Property Organization. 2020.

- ^ a b Circular 38A: International Copyright Relations of the United States (PDF). U.S. Copyright Office. 2014. p. 2. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ Borderless Publications, the Berne Convention, and U.S. Copyright Formalities, Jane C. Ginsburg, The Media Institute, 20 October 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ a b c d Berne Convention [1] Archived 23 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Berne Convention [2] Archived 23 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Berne Convention [3] Archived 23 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Brian F., Shi, Sampsung Xiaoxiang, Foong, Cheryl, & Pappalardo, Kylie M. (2011), "Country of Origin and Internet Publication : Applying the Berne Convention in the Digital Age". Journal of Intellectual Property (NJIP) Maiden Edition, pp. 38–73.

- ^ See for example the columns of Jane Ginsburg:

- Borderless Publications, the Berne Convention, and U.S. Copyright Formalities

- Internet Publication and U.S. Copyright Imperialism

- When a Work Debuts on the Internet, What Is its Country of Origin? Part II

- Chris Dombkowski, SIMULTANEOUS INTERNET PUBLICATION AND THE BERNE CONVENTION, SANTA CLARA COMPUTER & HIGH TECH. L.J., vol. 29, pp. 643–674

- ^ a b c Berne Convention Article 7.

- ^ Drier, Thomas; Hugenholtz, P. Bernt (2016). Concise European Copyright Law (2 ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- ^ Okediji, Ruth. "Toward an International Fair Use Doctrine". Columbia Journal of Transnational Law. 39: 75. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ Travis, Hannibal (2008). "Opting Out of the Internet in the United States and the European Union: Copyright, Safe Harbors, and International Law". Notre Dame Law Review, vol. 84, p. 383. President and Trustees of Notre Dame University in South Bend, Indiana. SSRN 1221642.

- ^ See United States – Section 110(5) of the U.S. Copyright Act.

- ^ a b Travis, p. 373.

- ^ There Can Be No 'Balance' In The Entirely Unbalanced System Of Copyright – Techdirt, Mike Masnick, 1 March 2012

- ^ "Quick Berne Convention Overview". Laws.com. 4 April 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ Dutfield, Graham (2008). Global Intellectual Property Law. Edward Elger Pub. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-1-843769422.

- ^ Baldwin, Peter (2016). The Copyright Wars: Three Centuries of Trans-Atlantic Battle. Princeton University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-691169095.

- ^ "A Brief History of Copyright". Intellectual Property Rights Office.

- ^ "The Netherlands and the Berne Convention". The Publishers' circular and booksellers' record of British and foreign literature, Vol. 71. Sampson Low, Marston & Co. 1899. p. 597. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ "Summary of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (1883)". World Intellectual Property Organization. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ a b "WIPO - A Brief History". World Intellectual Property Organization. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ Cook, Curtis (2002). Patents, Profits & Power: How Intellectual Property Rules the Global Economy. Kogan Page. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-749442729.

- ^ "Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works". World Intellectual Property Organization. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ "WIPO Copyright Treaty". World Intellectual Property Organization. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ Solberg, Thorvald (1908). Report of the Delegate of the United States to the International Conference for the Revision of the Berne Copyright Convention, Held at Berlin, Germany, 14 October to 14 November 1908. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. p. 9.

- ^ a b "Contracting Parties > Berne Convention (Total Contracting Parties : 173)". WIPO - World Intellectual Property Organization. WIPO. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ "Treaties in Force – A List of Treaties and Other International Agreements of the United States in Force on January 1, 2016" (PDF). www.state.gov.

- ^ WIPO's "Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (Paris Text 1971)", http://zvon.org/law/r/bern.html

- ^ Brazilian's Federal Decree No. 75699 6 May 1975. urn:lex:br:federal:decreto:1975;75699

- ^ Molotsky, Irvin (21 October 1988). "Senate Approves Joining Copyright Convention". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ Fishman, Stephen (2011). The Copyright Handbook: What Every Writer Needs to Know. Nolo Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-1-4133-1617-9. OCLC 707200393.

The UCC is not nearly as important as it used to be. Indeed, it's close to becoming obsolete

- ^ "Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works". World Intellectual Property Organisation.

- ^ Ricketson, Sam (2018). "The International Framework for the Protection of Authors: Bendable Boundaries and Immovable Obstacles". Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts. 41: 341, 348–352. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Ricketson, Sam (2018). "The International Framework for the Protection of Authors: Bendable Boundaries and Immovable Obstacles". Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts. 41: 341, 353 (2018) (citing iconic Australian film "The Castle"). Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Berne Convention, Article 20.

- ^ Giblin, Rebecca (2019). A Future of International Copyright? Berne and the Front Door Out. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. SSRN 3351460.

External links

[edit]- The full text of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (as amended on 28 September 1979) (in English) in the WIPO Lex database – official website of WIPO.

- "Guide to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (Paris text, 1971)" (PDF). WIPO. Geneva: World Intellectual Property Organization. 1978.

- WIPO-Administered Treaties (in English) in the WIPO Lex database – official website of WIPO.

- The 1971 Berne Convention text – fully indexed and crosslinked with other documents

- Texts of the various Berne Convention revisions:

- World Intellectual Property Organization treaties

- Intellectual property law of the European Union

- Copyright treaties

- 1886 treaties

- Treaties entered into force in 1887

- Treaties of Afghanistan

- Treaties of Albania

- Treaties of Algeria

- Treaties of Andorra

- Treaties of Antigua and Barbuda

- Treaties of Argentina

- Treaties of Armenia

- Treaties of Australia

- Treaties of the First Austrian Republic

- Treaties of Azerbaijan

- Treaties of the Bahamas

- Treaties of Bahrain

- Treaties of Bangladesh

- Treaties of Barbados

- Treaties of Belarus

- Treaties of Belgium

- Treaties of Belize

- Treaties of the Republic of Dahomey

- Treaties of Bhutan

- Treaties of Bolivia

- Treaties of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Treaties of Botswana

- Treaties of the First Brazilian Republic

- Treaties of Brunei

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Bulgaria

- Treaties of Burkina Faso

- Treaties of Burundi

- Treaties of Cameroon

- Treaties of Cambodia

- Treaties of Canada

- Treaties of Cape Verde

- Treaties of the Central African Republic

- Treaties of Chad

- Treaties of Chile

- Treaties of the People's Republic of China

- Treaties of the United States of Colombia

- Treaties of the Comoros

- Treaties of the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville)

- Treaties of the Republic of the Congo

- Treaties of the Cook Islands

- Treaties of Costa Rica

- Treaties of Ivory Coast

- Treaties of Croatia

- Treaties of Cuba

- Treaties of Cyprus

- Treaties of the Czech Republic

- Treaties of Czechoslovakia

- Treaties of Denmark

- Treaties of Djibouti

- Treaties of the Dominican Republic

- Treaties of Dominica

- Treaties of Ecuador

- Treaties of Egypt

- Treaties of El Salvador

- Treaties of Equatorial Guinea

- Treaties of Estonia

- Treaties of Fiji

- Treaties of Finland

- Treaties of the French Third Republic

- Treaties of Gabon

- Treaties of the Gambia

- Treaties of Georgia (country)

- Treaties of the German Empire

- Treaties of Ghana

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Greece

- Treaties of Grenada

- Treaties of Guatemala

- Treaties of Guinea

- Treaties of Guinea-Bissau

- Treaties of Guyana

- Treaties of Haiti

- Treaties of Honduras

- Treaties extended to Hong Kong

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1946)

- Treaties of Iceland

- Treaties of British India

- Treaties of Indonesia

- Treaties of the Irish Free State

- Treaties of Israel

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

- Treaties of Jamaica

- Treaties of the Empire of Japan

- Treaties extended to Jersey

- Treaties of Jordan

- Treaties of Kazakhstan

- Treaties of Kenya

- Treaties of Kiribati

- Treaties of North Korea

- Treaties of South Korea

- Treaties of Kuwait

- Treaties of Kyrgyzstan

- Treaties of Laos

- Treaties of Latvia

- Treaties of Lebanon

- Treaties of Lesotho

- Treaties of Liberia

- Treaties of Liechtenstein

- Treaties of Lithuania

- Treaties of Luxembourg

- Treaties extended to Macau

- Treaties of North Macedonia

- Treaties of Madagascar

- Treaties of Malawi

- Treaties of Malaysia

- Treaties of Mali

- Treaties of Malta

- Treaties of Mauritania

- Treaties of Mauritius

- Treaties of Mexico

- Treaties of the Federated States of Micronesia

- Treaties of Moldova

- Treaties of Monaco

- Treaties of Mongolia

- Treaties of Montenegro

- Treaties of Morocco

- Treaties of Mozambique

- Treaties of Namibia

- Treaties of Nauru

- Treaties of Nepal

- Treaties of the Netherlands

- Treaties of New Zealand

- Treaties of Nicaragua

- Treaties of Niger

- Treaties of Nigeria

- Treaties of Niue

- Treaties of Norway

- Treaties of Oman

- Treaties of the Dominion of Pakistan

- Treaties of Panama

- Treaties of Paraguay

- Treaties of Peru

- Treaties of the Philippines

- Treaties of the Second Polish Republic

- Treaties of the Portuguese First Republic

- Treaties of Qatar

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Romania

- Treaties of Russia

- Treaties of Rwanda

- Treaties of Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Treaties of Saint Lucia

- Treaties of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Treaties of Samoa

- Treaties of San Marino

- Treaties of São Tomé and Príncipe

- Treaties of Saudi Arabia

- Treaties of Senegal

- Treaties of Serbia and Montenegro

- Treaties of Singapore

- Treaties of Slovakia

- Treaties of Slovenia

- Treaties of the Union of South Africa

- Treaties of the Solomon Islands

- Treaties of Spain under the Restoration

- Treaties of the Dominion of Ceylon

- Treaties of the Republic of the Sudan (1985–2011)

- Treaties of Suriname

- Treaties of Eswatini

- Treaties of Switzerland

- Treaties of Sweden

- Treaties of Syria

- Treaties of Tajikistan

- Treaties of Tanzania

- Treaties of Thailand

- Treaties of Togo

- Treaties of Tonga

- Treaties of Turkmenistan

- Treaties of Trinidad and Tobago

- Treaties of Tunisia

- Treaties of Turkey

- Treaties of Tuvalu

- Treaties of Uganda

- Treaties of Ukraine

- Treaties of the United Arab Emirates

- Treaties of the United Kingdom (1801–1922)

- Treaties of the United States

- Treaties of Uruguay

- Treaties of Uzbekistan

- Treaties of Vanuatu

- Treaties of the Holy See

- Treaties of Venezuela

- Treaties of Vietnam

- Treaties of Yemen

- Treaties of Zambia

- Treaties of Yugoslavia

- Treaties of Zimbabwe

- 1886 in Switzerland

- Treaties extended to Ashmore and Cartier Islands

- Treaties extended to the Australian Antarctic Territory

- Treaties extended to Christmas Island

- Treaties extended to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Treaties extended to the Coral Sea Islands

- Treaties extended to Heard Island and McDonald Islands

- Treaties extended to Norfolk Island

- Treaties extended to the Netherlands Antilles

- Treaties extended to Aruba

- Treaties extended to the Isle of Man

- Treaties extended to West Berlin

- Treaties extended to Guernsey

- September 1886 events

- Events in Bern