Benjamin Spock

Benjamin Spock | |

|---|---|

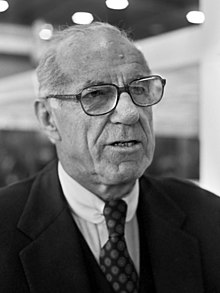

Spock in 1976 | |

| Born | Benjamin McLane Spock May 2, 1903 New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | March 15, 1998 (aged 94) San Diego, California, U.S. |

| Education | Yale University (BA) Columbia University (MD) |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Marjorie Spock (sister) |

| Awards | E. Mead Johnson Award (1948) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Pediatrics, psychoanalysis |

| Institutions | Mayo Clinic 1947–1951 University of Pittsburgh 1951–1955 Case Western Reserve University 1955–1967 |

| Signature | |

Benjamin McLane Spock (May 2, 1903 – March 15, 1998), widely known as Dr. Spock, was an American pediatrician[1] and left-wing political activist.[2] His book Baby and Child Care (1946) is one of the best-selling books of the 20th century, selling 500,000 copies in the six months after its initial publication and 50 million by the time of Spock's death in 1998.[3] The book's premise told mothers, "You know more than you think you do."[4] Dr. Spock was widely regarded as a trusted source for parenting advice in his generation.[5]

Spock was the first pediatrician to study psychoanalysis in an effort to understand children's needs and family dynamics. His ideas influenced several generations of parents, encouraging them to be more flexible and affectionate with their children and to treat them as individuals. However, his theories were widely criticized by colleagues for relying heavily on anecdotal evidence rather than serious academic research.[6]

After undergoing a self-described "conversion to socialism", Spock became an activist in the New Left and anti-Vietnam War movements during the '60s and early '70s, culminating in his run for President of the United States as the People's Party nominee in 1972. He campaigned on a maximum wage, legalized abortion, and withdrawing troops from all foreign countries. His books were criticized by conservatives for propagating permissiveness and an expectation of instant gratification, a charge that Spock denied.[7]

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]| Medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Men's rowing | ||

| Representing the | ||

| Olympic Games | ||

| 1924 Paris | Eight | |

Benjamin McLane Spock was born May 2, 1903, in New Haven, Connecticut. His parents were Benjamin Ives Spock, Yale graduate and long-time general counsel of the New Haven Railroad, and Mildred Louise (Stoughton) Spock.[1] The family name had Dutch origins; they originally spelled it Spaak before migrating to the former colony of New Netherland.[8] Spock was one of six children, including his younger sister, environmentalist writer Marjorie Spock.[9]

Spock attended Hamden Hall Country Day School, and went on to attend his father's alma maters Phillips Andover Academy and Yale University. He studied literature and history at Yale; the lanky 6' 4" Spock was also active in college rowing. Eventually, he joined the Olympic rowing crew (Men's Eights) that won a gold medal at the 1924 games in Paris.[10] At Yale, he was inducted into the Eta chapter of the Zeta Psi fraternity and the senior society Scroll and Key. He attended the Yale School of Medicine for two years before shifting to Columbia University's College of Physicians and Surgeons, from which he graduated first in his class in 1929.[11] By that time, he had married Jane Cheney.[12]

Personal life

[edit]Jane Cheney and Spock were married in 1927. Jane assisted Spock in the research and writing of Dr. Spock's Baby & Child Care, published in 1946 by Duell, Sloan & Pearce as The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care. The book has sold more than 50 million copies in 42 languages.[13][14]

Jane Cheney Spock was a civil liberties advocate and mother of two sons. She was born in Manchester, Connecticut, and attended Bryn Mawr College. She was active in Americans for Democratic Action, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy. The Spocks divorced in 1976.[15] Cheney went on to organize and run support groups for older divorced women.[16]

In 1976, Spock married Mary Morgan.[17] They built a home on Beaver Lake in Arkansas where Spock would row daily.[18] Mary quickly adapted to Spock's life of travel and political activism, and was arrested with him many times for civil disobedience. Once they were arrested in Washington, D.C. for praying on the White House lawn. Morgan was strip-searched; Spock was not. Morgan sued the jail and the mayor of Washington, D.C. for sex discrimination. The ACLU took the case and won.

For most of his life, Spock wore Brooks Brothers suits and shirts with detachable collars, but at 75, for the first time in his life, Mary got him to try blue jeans. She joined him in meditation twice a day and introduced him to Transactional analysis (TA) therapists, massage, yoga and a macrobiotic diet which reportedly improved his health. "She gave me back my youth," Spock was quoted as saying. He adapted to her lifestyle, as she did to his. There were 40 years difference in their ages, but Spock would tell reporters they were both 16.[citation needed] Mary scheduled speaking dates and handled legal agreements for the 5th through 9th editions of Baby and Child Care. She continues to publish the book with co-author Robert Needlman.

For many years, Spock lived aboard his sailboat, the Carapace, in the British Virgin Islands off Tortola.[19] At 84, Spock won third place in a rowing contest, crossing four miles (6.4 km) of the Sir Francis Drake Channel between Tortola and Norman Island in 2.5 hours.[20] He credited his strength and good health to his lifestyle and his love for life.[13] Spock had a second sailboat named Turtle, which he lived aboard and sailed in Maine in the summers. The Spocks lived only on boats for most of 20 years.

By 1991, Spock was unable to walk without assistance and was reported as infirm shortly before his death.[21][22] At the very end of Spock's life, he was advised to come ashore by his physician, Steve Pauker, of New England Medical Center, Boston. In 1992, Spock received the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience Award at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library for his lifelong commitment to disarmament and peaceable child-rearing.[23][24]

Spock had two sons.[citation needed]

Spock died at a house he was renting in La Jolla, California, on March 15, 1998. His ashes were buried in Rockport, Maine, where he spent his summers.[citation needed]

Books

[edit]In 1946, Spock published The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care, which became a best-seller. Its message to parents is "You know more than you think you do."[4] By 1998, it had sold more than 50 million copies, and had been translated into 42 languages.[13][14] According to the New York Times, Baby and Child Care was, throughout its first 52 years, the second-best-selling book, next to the Bible.[21] According to other sources, it was among best-sellers, albeit not second-best-selling.[citation needed]

Spock advocated ideas about parenting that were considered out of the mainstream. Over time, his books helped to bring about major change. Previously, experts (such as Truby King) had told parents babies needed to learn to sleep on a regular schedule, and that picking them up and holding them when they cried would only teach them to cry more and not to sleep through the night (a notion that borrows from behaviorism). They were told[citation needed] to feed their children on a regular schedule, and that they should not pick them up, kiss them, or hug them, because that would not prepare them to be strong, independent individuals in a harsh world. In contrast, Spock encouraged parents to show affection for their children and to see them as individuals.[citation needed]

By the late 1960s, however, Spock's opposition to the Vietnam War had damaged his reputation. The 1968 edition of Baby and Child Care sold half as many copies of the prior edition.[citation needed] Later in life, Spock wrote Dr. Spock on Vietnam and co-wrote an autobiography entitled Spock on Spock (with wife Mary Morgan Spock), in which he stated his attitude toward aging: Delay and Deny.[25]

In the seventh edition of Baby and Child Care published shortly after he died, Spock advocated for a bold change in children's diets, recommending children switch to a vegan diet after age 2.[26] Spock himself had switched to an all-plant diet in 1991 after a series of illnesses that left him weak and unable to walk unaided. After making the dietary change, he lost 50 pounds, regained his ability to walk and became healthier overall. The revised edition stated children on an all-plant diet will reduce their risk of developing heart disease, obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes and certain diet-related cancers. Studies suggest that vegetarian children are leaner, and adult vegetarians are known to be at lower risk of such diseases.[27] However, Spock's recommendations were criticized as being irresponsible towards children's health and children's ability to sustain normal growth, which has been aided with minerals such as calcium, riboflavin, vitamin D, iron, zinc and at times protein.[21]

Spock's approach to childhood nutrition was criticized by a number of experts, including co-author Boston pediatrician Steven J. Parker,[28] as too extreme and likely to result in nutritional deficiencies unless it was carefully planned and executed, which would be difficult for working parents.[21] T. Berry Brazelton, Boston City Hospital pediatrician who specialized in child behavior (and longtime admirer and friend of Dr. Spock), called the dietary recommendations "absolutely insane."[21] Neal Barnard, president of Physicians for Responsible Medicine, a Washington organization advocating strict vegetarian diets, acknowledged he drafted the nutrition section in the 1998 edition of Baby and Child Care, but said Spock edited it to give it "his personal touch."[21] It was acknowledged that in Spock's final years, he had strokes, bouts with pneumonia and a heart attack.[29]

Views

[edit]Sudden infant death syndrome

[edit]Spock advocated that infants should not sleep on their backs, commenting in his 1958 edition that "if [an infant] vomits, he's more likely to choke on the vomitus." This advice was extremely influential on healthcare providers, with nearly unanimous support through the 1990s.[30] Later empirical studies, however, found a significantly increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) associated with infants sleeping on their abdomens. Advocates of evidence-based medicine have used this as an example of the importance of basing healthcare recommendations on statistical evidence. One researcher estimated that as many as 50,000 infant deaths in Europe, Australia, and the U.S. could have been prevented had this advice been changed by 1970 when such evidence became available.[31]

Male circumcision

[edit]In the 1940s, Spock favored circumcision of males performed within a few days of birth. However, in the 1976 revision of Baby and Child Care he concurred with a 1971 American Academy of Pediatrics task force that there was no medical reason to recommend routine circumcision, and in a 1989 article for Redbook he stated that "circumcision of males is traumatic, painful, and of questionable value."[32] He received the first Human Rights Award from the International Symposium on Circumcision (ISC) in 1991 and was quoted as saying, "My own preference, if I had the good fortune to have another son, would be to leave his little penis alone."[33]

Social and political activism

[edit]In 1962, Spock joined The Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, otherwise known as SANE. Spock was politically outspoken and active in the movement to end the Vietnam War. In 1968, he and four others (including William Sloane Coffin, Marcus Raskin, Mitchell Goodman, and Michael Ferber) were singled out for prosecution by then Attorney General Ramsey Clark on charges of conspiracy to counsel, aid, and abet resistance to the draft.[34] Spock and three of his alleged co-conspirators were convicted, although the five had never been in the same room together. His two-year prison sentence was never served; the case was appealed, and in 1969 a federal court set aside his conviction.[35]

In 1967, Spock was pressed to run as Martin Luther King Jr.'s vice-presidential running mate at the National Conference for New Politics over Labor Day weekend in Chicago.[36] In April of that year, Spock helped lead the largest anti-war protest to date, the Spring Mobilization Against the War. Spock wore a suit and held a sign that read "Children are not born to burn."[37]

In 1968, Spock signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest" pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War,[38] and he later became a sponsor of the War Tax Resistance project, which practiced and advocated tax resistance as a form of anti-war protest.[39] He was also arrested for his involvement in anti-war protests resulting from his signing of the anti-war manifesto "A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority" circulated by members of the radical intellectual collective RESIST.[40] The individuals arrested during this incident came to be known as the Boston Five.[41]

In 1968, the American Humanist Association named Spock Humanist of the Year.[42] On 15 October 1969, Spock was a featured speaker at the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam march.[43]

In 1970, Dr. Benjamin Spock was active in The New Party serving as Honorary co-chairman with Gore Vidal. In the 1972 United States presidential election, Spock was the People's Party candidate with a platform that called for free medical care; the repeal of "victimless crime" laws, including the legalization of abortion, homosexuality, and cannabis; a guaranteed minimum income for families; and for an end to American military interventionism and the immediate withdrawal of all American troops from foreign countries.[44] In the 1970s and 1980s, Spock demonstrated and gave lectures against nuclear weapons and cuts in social welfare programs.[citation needed]

In 1972, Spock, Julius Hobson (his vice presidential candidate), Linda Jenness (Socialist Workers Party presidential candidate), and Socialist Workers Party vice presidential candidate Andrew Pulley wrote to Major General Bert A. David, commanding officer of Fort Dix, asking for permission to distribute campaign literature and to hold an election-related campaign meeting. On the basis of Fort Dix regulations 210-26 and 210–27, General David refused the request. Spock, Hobson, Jenness, Pulley, and others then filed a case that ultimately made its way to the United States Supreme Court (424 U.S. 828—Greer, Commander, Fort Dix Military Reservation, et al., v. Spock et al.), which ruled against the plaintiffs.[45]

Spock was the People's Party and the Peace and Freedom Party nominee in 1976 for vice president as the running mate of Margaret Wright.[46]

Conservative backlash

[edit]Preacher Norman Vincent Peale supported the Vietnam War and, in the late '60s, criticized the anti-war movement and the perceived laxity of that era, blaming Dr. Spock's books: "The U.S. was paying the price of two generations that followed the Dr. Spock baby plan of instant gratification of needs."[47]

In the '60s and '70s, Spock was also blamed for the disorderliness of young people, many of whose parents had been devotees of Baby and Child Care.[13] Vice President Spiro Agnew also blamed Spock for "permissiveness".[13][48] These allegations were enthusiastically embraced by conservative adults, who viewed the rebellious youth of that era with disapproval, referring to them as "the Spock generation".[49][50][51]

Spock's supporters countered that these criticisms betrayed an ignorance of what Spock had actually written, and/or a political bias against Spock's left-wing political activities. Spock himself, in his autobiography, said he had never advocated permissiveness; also, the attacks and claims that he had ruined American youth only arose after his public opposition to the Vietnam War. He regarded these claims as ad hominem attacks, whose political motivation and nature were clear.[49][50]

Spock addressed these accusations in the first chapter of his 1994 book, Rebuilding American Family Values: A Better World for Our Children.

The Permissive Label: A couple weeks after my indictment [for "conspiracy to counsel, aid and abet resistance to the military draft"], I was accused by Reverend Norman Vincent Peale, a well-known clergyman and author who supported the Vietnam War, of corrupting an entire generation. In a sermon widely reported in the press, Reverend Peale blamed me for all the lack of patriotism, lack of responsibility, and lack of discipline of the young people who opposed the war. All these failings, he said, were due to my having told their parents to give them "instant gratification" as babies. I was showered with blame in dozens of editorials and columns from primarily conservative newspapers all over the country heartily agreeing with Peale's assertions.

Many parents have since stopped me on the street or in airports to thank me for helping them to raise fine children, and they've often added, "I don't see any instant gratification in Baby and Child Care". I say they're right—I've always advised parents to give their children firm, clear leadership and to ask for cooperation and politeness in return. On the other hand, I've also received letters from conservative mothers saying, in effect, "Thank God I've never used your horrible book. That's why my children take baths, wear clean clothes and get good grades."

Since I received the first accusation 22 years after Baby and Child Care was originally published—and since those who write about how harmful my book is invariably assure me they've never used it—I think it's clear that the hostility is to my politics rather than my pediatric advice. And though I've been denying the accusation for 25 years, one of the first questions I get from many reporters and interviewers is, "Dr. Spock, are you still permissive?" You can't catch up with a false accusation.

In June 1992, Spock told Associated Press journalist David Beard[52] there was a link between pediatrics and political activism:

People have said, "You've turned your back on pediatrics." I said, "No. It took me until I was in my 60s to realize that politics was a part of pediatrics."[52][53]

Conservatives also criticized Spock for being interested in the ideas of Sigmund Freud and John Dewey and his efforts to integrate their philosophies into the general population.[13] Spock wrote:

John Dewey and Freud said that kids don't have to be disciplined into adulthood but can direct themselves toward adulthood by following their own will.[13]

Olympic success

[edit]Spock was part of the all-Yale Men's eight rowing team at the 1924 Summer Olympics, captained by James Rockefeller (later president of what would become Citigroup). Competing on the Seine, the team won the gold medal.[54]

Pop culture references

[edit]I Love Lucy mentions Dr. Spock twice. In "Nursery School", Lucy quotes a sentence from his child care book out of context to justify her not sending Little Ricky to nursery school. Ricky then reads the rest of the passage, all of which applies to Little Ricky's home life situation, causing Lucy to ask, ""Well, what does he know?" Ricky then asserts that he and "Dr. Spook" agree about nursery school. Lucy corrects Ricky and asks how Spock knew this, and was he ever a mother.

In "Little Ricky's School Pageant", when Lucy and Ricky discuss Little Ricky's role in a school play, Ricky tells Lucy that it's more important that their son learn to cooperate with others than have a big part in the play. Lucy then calls her husband a Cuban Dr. Spock.

Books by Benjamin Spock

[edit]- Baby and Child Care (1946, with revisions up to tenth edition, 2018)

- A Baby's First Year (1954)

- Feeding Your Baby and Child (1955)

- Dr. Spock Talks With Mothers (1961)

- Problems of Parents (1962)

- Caring for Your Disabled Child (1965)

- Dr. Spock on Vietnam (1968)

- Decent and Indecent (1970)

- A Teenager's Guide to Life and Love (1970)

- Raising Children in a Difficult Time (1974)

- Spock on Parenting (1988)

- Spock on Spock: a Memoir of Growing Up With the Century (1989)

- A Better World for Our Children (1994)[13]

- Dr. Spock's the School Years: The Emotional and Social Development of Children 01 Edition (2001)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Barnes, Bart (2024-01-08). "Pediatrician Benjamin Spock Dies". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ^ Downes, Lawrence (March 22, 1998). "Word for Word / Dr. Spock; Time to Change the Baby Advice: Evolution of a Child-Care Icon". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- ^ Thomas Maier, Dr. Spock: An American Life (New York: Basic Books, 2003), 462.

- ^ a b Hidalgo, Louise (August 23, 2011). "Dr Spock's Baby and Child Care at 65". BBC News. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ McNair, Kamaron (August 16, 2024). "'Neither of us feel interested': More Americans don't want kids, and it's not just because of the money". CNBC. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ Maier, 260.

- ^ Pace, Eric (March 17, 1998). "Benjamin Spock, World's Pediatrician, Dies at 94". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ "Benjamin Spock -New Netherland Institute". New Netherland Institute. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Postel, Sandra (2020). "Marjorie Spock: An Unsung Hero in the Fight Against DDT and in the Rise of the Modern Environmental Movement" (PDF). The Nassau County Historical Society Journal. 75. Nassau County, New York: Nassau County Historical Society: 2.

- ^ "Benjamin Spock". Olympedia. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ Biography of Spock at drspock.com

- ^ Kochakian, Mary Jo (June 14, 1998). "Public vs. Private: Dr. Spock, Mr. Hyde". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pace, Eric (March 17, 1998). "Benjamin Spock, World's Pediatrician, Dies at 94". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Dr. Spock's baby book will endure". CNN. March 16, 1998. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Klemesrud, Judy (March 19, 1976). "The Spocks: Bittersweet Recognition in a Revised Classic". The New York Times.

- ^ "Jane C. Spock, 82; Worked on Baby Book". The New York Times. June 14, 1989. p. D25. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Lawson, Carol (March 5, 1992). "At 88, an Undiminished Dr. Spock". The New York Times.

- ^ "Dr. Spock: He's newborn at 75". February 18, 1979. p. I1.

- ^ "Mary Morgan: Spock's wife also caretaker". Daily Breeze (Torrance, CA). 29 April 1990.

- ^ "BENJAMIN McLANE SPOCK (1903-1998) - den kontroversielle rebellen". Tidsskrift for Norsk Barnelegeforening. 34 (1): 26–28. 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Brody, Jane E. (June 20, 1998). "Final Advice From Dr. Spock: Eat Only All Your Vegetables". The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ^ Carvajal, Doreen (February 28, 1998). "Dr. Spock, Old and Infirm, Needs Money, Wife Says". The New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ "Recipients of the Courage of Conscience Award | The Peace Abbey FoundationThe Peace Abbey Foundation". www.peaceabbey.org. 2 May 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Fensch, Thomas (2014). At the Dangerous Edge of Social Justice: Race, Violence and Death in America. New Century Books. p. 254. ISBN 978-0983229667.

- ^ Spock, Benjamin (1989). Spock on Spock. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 254. ISBN 0394578139.

- ^ Jane E. Brody, PERSONAL HEALTH; Feeding Children off the Spock Menu, The New York Times, June 30, 1998. p. F7.

- ^ Dunham, Laurie; Kollar, Linda M. (January 2006). "Vegetarian Eating for Children and Adolescents". Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 20 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.08.012. ISSN 0891-5245. PMID 16399477.

- ^ Beck, Joan (June 25, 1998). "Dr. Spock's Irresponsible Legacy". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "Baby Doctor for the Millions Dies". Los Angeles Times. March 17, 1998. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Ruth Gilbert; Georgia Salanti; Melissa Harden; Sarah See (2005). "Infant sleeping position and the sudden infant death syndrome: systematic review of observational studies and historical review of recommendations from 1940 to 2002". International Journal of Epidemiology. 34 (4). Oxford University Press: 874–87. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.488.3870. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi088. PMID 15843394.

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Corporation. "Health Report", September 11, 2006. Radio program. Transcript

- ^ Spock, Benjamin (April 1989), "Circumcision - It's Not Necessary", Redbook, Canadian Children's Rights Council

- ^ Milos, Marilyn Fayre; Donna Macris (March–April 1992). "Circumcision: A medical or a human rights issue?". Journal of Nurse-Midwifery. 37 (2 S1): S87–S96. doi:10.1016/0091-2182(92)90012-R. PMID 1573462.

- ^ The William Sloane Coffin, Jr. Project Committee. "Once to Every Man and Nation". Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ See United States v. Spock, 416 F.2d 165 (1st Cir. 1969).

- ^ Manly, Chesly (August 27, 1967). "'New Politics' Convention to Open Here". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Perlstein, Rick (2008). Nixonland : the rise of a president and the fracturing of America. Internet Archive. New York : Scribner. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-7432-4302-5.

- ^ "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest". New York Post. January 30, 1968.

- ^ "A Call to War Tax Resistance" The Cycle May 14, 1970, p. 7.

- ^ Barsky, Robert F. Noam Chomsky: a life of dissent. 1st ed. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, 1998. Web. "Marching with the Armies of the Night". Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2014.>

- ^ Kutik, William M,. "Boston Grand Jury Indicts Five For Working Against Draft Law". Harvard Crimson. January 8, 1968.

- ^ "Humanists of the Year". American Humanist Association. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Karnow, Stanley Vietnam: A History, New York: Viking Press, 1983 p. 599.

- ^ "8 Unusual Presidential Candidates". History Channel. March 22, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "Greer v. Spock 424 U.S. 828 (1976)". Justia. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ "Radical Launches Bid", AP report in Scranton (PA) Times-Tribune, August 7, 1976, p. 1

- ^ LIFE 100 People Who Changed the World. Time Inc. Books. 2016. ISBN 9781618934710.

- ^ Permissiveness? Not Dr. Spock, Says Widow, Rejecting Label from Nixon's VP, Spiro Agnew. Spock So-So On Spanking, But He Wasn't a Crook! Thomas Maire author of Dr. Spock An American Life July 16, 2008.

- ^ a b Reed, Roy (May 2, 1983). "Dr. Spock, At 80, Still Giving Advice". The New York Times. p. A12.

- ^ a b "Remembering Dr. Spock". The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. March 16, 1998. PBS.

- ^ "Spock Generation Not all bad". Windsor Star. Associated Press. October 7, 1968 – via Google News.

- ^ a b Beard, David (June 7, 1992). "Dr. Spock Still Active, Writing New Baby Book". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press.

- ^ William H. Thomas (March 11, 2014). Second Wind: Navigating the Passage to a Slower, Deeper, and More Connected Life. Simon & Schuster. p. 21. ISBN 9781451667578.

- ^ "Rowing at the 1924 Paris Summer Games: Men's Coxed Eights". Sports Reference. Archived from the original on April 18, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Bloom, Lynn Z. Doctor Spock: Biography of a Conservative Radical. The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Indianapolis: 1972.

- Maier, Thomas. Doctor Spock: An American Life. Harcourt Brace, New York: 1998.

- Interview in The Libertarian Forum 4, no. 12 (December 1972; mislabelled no. 10). The Libertarian Forum is largely favorable to Spock's views as being pro-libertarian.

External links

[edit]- Benjamin Spock at IMDb

- Benjamin Spock Papers at Syracuse University

- Photos of the 1st edition of The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care

- Details surrounding the 1968 case

- Photographic portrait taken in old age

- A film clip "The Open Mind - American Values and the College Generation (1974)" is available for viewing at the Internet Archive

- Audio: Benjamin Spock speech at UC Berkeley Vietnam Teach-In, 1965 (in RealAudio and via UC Berkeley Media Resources Center)

- Benjamin Spock at Find a Grave

- 1903 births

- 1998 deaths

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American physicians

- 20th-century American politicians

- Candidates in the 1972 United States presidential election

- 1976 United States vice-presidential candidates

- American anti–nuclear weapons activists

- American anti–Vietnam War activists

- American family and parenting writers

- American humanists

- American male non-fiction writers

- American male rowers

- 20th-century American memoirists

- United States Navy personnel of World War II

- American pediatricians

- American people of Dutch descent

- American tax resisters

- Analysands of Sándor Radó

- Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons alumni

- Medalists at the 1924 Summer Olympics

- Military personnel from New Haven, Connecticut

- New Left

- Olympic gold medalists for the United States in rowing

- People's Party (United States, 1971) politicians

- Phillips Academy alumni

- Physicians from New Haven, Connecticut

- Politicians from New Haven, Connecticut

- Rowers at the 1924 Summer Olympics

- United States Navy officers

- University of Pittsburgh faculty

- Writers from New Haven, Connecticut

- Yale College alumni

- Hamden Hall Country Day School alumni

- Macrobiotic diet advocates