Benefit corporation

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Corporate law |

|---|

|

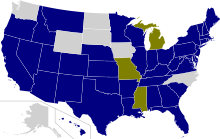

Passed into law.

No existing law.

Bill failed a vote in the state's legislature.

In business, and only in United States corporate law, a benefit corporation (or in some states, a public benefit corporation) is a type of for-profit corporate entity whose goals include making a positive impact on society. Laws concerning conventional corporations typically do not define the "best interest of society", which has led some to believe that increasing shareholder value (profits and/or share price) is the only overarching or compelling interest of a corporation.[1] Benefit corporations explicitly specify that profit is not their only goal.[2] An ordinary corporation may change to a benefit corporation merely by stating in its approved corporate bylaws that it is a benefit corporation.[2]

A company chooses to become a benefit corporation in order to operate as a traditional for-profit business while simultaneously addressing social, economic, and/or environmental needs.[3] For example, a 2013 study done by MBA students at the University of Maryland showed that one main reason businesses in Maryland had chosen to file as benefit corporations was for community recognition of their values.[4] A benefit corporation's directors and officers operate the business with the same authority and behavior as in a traditional corporation, but are required to consider the impact of their decisions not only on shareholders but also on employees, customers, the community, and the local and global environment. For an example of what additional impacts directors and officers are required to consider, view the Maryland Code § 5-6C-07 – Duties of director. The nature of the business conducted by the corporation does not affect its status as a benefit corporation. Instead, it provides a justification for including public benefits in their missions and activities.

The benefit corporation legislation ensures that a director is required to consider other public benefits in addition to profit, preventing shareholders from using a drop in stock value as evidence for dismissal or a lawsuit against the corporation. Transparency provisions require benefit corporations to publish annual benefit reports of their social and environmental performance using a comprehensive, credible, independent, and transparent third-party standard. However, few of the states have included provisions for the removal of benefit corporation status or fines if the companies fail to publish benefit reports that comply with the state statutes.[5]

Currently, there are no legal standards that define what constitutes a benefit corporation.[6] A benefit corporation need not be certified or audited by the third-party standard. Instead, it may use third-party standards solely as a rubric to measure its own performance. Some authors have pointed out that in the current 36 states that recognize benefit corporations, the laws requiring certification for operation differ from state to state.[7] For example, in the state of Indiana, there is no requirement for certification from a third party needed to operate as a benefit corporation.[8] Other research has indicated a synergy between a benefit corporation and employee ownership.[9]

As a matter of law, in the 36 states that recognize this form of business, a benefit corporation is intended "to merge the traditional for-profit business corporation model with a non-profit model by allowing social entrepreneurs to consider interests beyond those of maximizing shareholder wealth."[2]

History

[edit]United States

[edit]In April 2010, Maryland became the first U.S. state to pass benefit corporation legislation.[10] As of March 2018[update], 36 states and Washington, D.C., have passed legislation allowing for the creation of benefit corporations:[7]

| State | Date passed | Date in effect | Legislation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | December 31, 2020 | January 1, 2021 | Act 2020-73, §8.[11] |

| Arizona | April 30, 2013 | December 31, 2014 | SB 1238 Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine |

| Arkansas | April 19, 2013 | July 18, 2013 | HB 1510 |

| California | October 9, 2011 | January 1, 2012 | AB 361 for FPCs; revised and renamed as SPCs in 2015 via SB 1301 |

| Colorado | May 15, 2013 | April 1, 2014 | HB 13-1138 |

| Connecticut | April 24, 2014 | October 1, 2014 | SB 23, HB 5597 Section 140 |

| Delaware | July 17, 2013 | August 1, 2013 | SB 47 |

| Florida | June 20, 2014 | July 1, 2014 | SB 654, HB 685 |

| Hawaii | July 8, 2011 | July 8, 2011 | SB 298 |

| Idaho | April 2, 2015 | July 1, 2015 | SB 1076 |

| Illinois | August 2, 2012 | January 1, 2013 | SB 2897 |

| Indiana | April 30, 2015 | July 1, 2015 | HB 1015 |

| Iowa[12] | June 8, 2021 | June 8, 2021 | HB 844 |

| Kansas | March 30, 2017 | July 1, 2017 | HB 2153 |

| Kentucky | March 7, 2017 | July 1, 2017 | HB 35 Archived June 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine |

| Louisiana | May 31, 2012 | August 1, 2012 | HB 1178 |

| Maryland | April 13, 2010 | October 1, 2010 | SB 690/HB 1009 |

| Massachusetts | August 7, 2012 | December 1, 2012 | 2012 Acts, Chapter 238 |

| Minnesota | April 29, 2014 | January 1, 2015 | SF 2053, HF 2582 |

| Montana | April 27, 2015 | October 1, 2015 | HB 2458 |

| Nebraska | April 2, 2014 | July 18, 2014 | LB 751 |

| Nevada | May 24, 2013 | January 1, 2014 | AB 89 Archived June 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine |

| New Hampshire | July 11, 2014 | January 1, 2015 | SB 215 |

| New Jersey | January 10, 2011 | March 1, 2011 | S 2170 Archived September 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine |

| New Mexico | February 18, 2020 | February 18, 2020 | HB 118, Bill History |

| New York | December 12, 2011 | February 10, 2012 | A4692-a and S79-a |

| Oregon | June 18, 2013 | January 1, 2014 | HB 2296 |

| Pennsylvania | October 12, 2012 | January 1, 2013 | HB 1616 |

| Rhode Island | July 17, 2013 | January 1, 2014 | HB 5720 |

| South Carolina | June 6, 2012 | June 14, 2012 | HB 4766 |

| Tennessee | May 20, 2015 | January 1, 2016 | HB 0767/SB 0972 |

| Texas | June 14, 2017 | September 1, 2017 | HB 3488 |

| Utah | April 1, 2014 | May 13, 2014 | SB 133 |

| Vermont | May 19, 2010 | July 1, 2011 | S 263 |

| Virginia | March 26, 2011 | July 1, 2011 | HB 2358 |

| Washington | January 1, 2022 | Wash. Rev. Code § 24.03A.245 | |

| Washington, D.C. | February 8, 2013 | May 1, 2013 | B 19-058 Archived September 27, 2015, at the Wayback Machine |

| West Virginia | March 31, 2014 | July 1, 2014 | SB 202 |

| Wisconsin | November 27, 2017 | February 26, 2018 | SB298 Act 77 |

Connecticut's benefit corporation law is the first to allow "preservation clauses", which allow the corporation's founders to prevent it from reverting to a 'For Profit' entity at the will of their shareholders.[13]

Illinois established a new type of entity called the "benefit LLC", making the state the first to allow limited liability companies the same opportunities afforded to Illinois corporations under the state's benefit corporation law.[14][15]

Washington created social purpose corporations in 2012 with a similar focus and intent.[16][17]

Outside of the United States

[edit]Italy

[edit]In December 2015, the Italian Parliament passed legislation recognizing a new kind of organization, named Società Benefit, which was directly modeled after benefit corporations in the United States.[18][19][20][21][22]

Colombia

[edit]In 2018, Colombia introduced benefit corporation legislation.[23]

Canada

[edit]In May 2018, the leader of the British Columbia Green Party introduced a bill to amend the Business Corporations Act to permit the incorporation of "benefit companies" in British Columbia.[24] On June 30, 2020, British Columbia became the first province in Canada to offer the option of incorporating as a benefit company.[25][26][27]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, Community Interest Companies (CIC) were introduced in 2005, intended "for people wishing to establish businesses which trade with a social purpose..., or to carry on other activities for the benefit of the community".[28]

Differences from traditional corporations

[edit]Historically, U.S. corporate law has not been structured or tailored to address the situation of for-profit companies that wish to pursue a social or environmental mission.[29] While corporations generally have the ability to pursue a broad range of activities, corporate decision-making is usually justified in terms of creating long-term shareholder value.

The idea that a corporation has as its purpose to maximize financial gain for its shareholders was first articulated in Dodge v. Ford Motor Co. in 1919.[30] Over time, through both law and custom, the concept of "shareholder primacy" has come to be widely accepted. This was reaffirmed in 2010 for Delaware corporations by the case eBay Domestic Holdings, Inc. v. Craig Newmark, et al., 3705-CC, 61 (Del. Ch. 2010)., in which the Delaware Chancery Court stated that a non-financial mission that "seeks not to maximize the economic value of a for-profit Delaware corporation for the benefit of its stockholders" is inconsistent with directors' fiduciary duties. However, the fiduciary duties do not list profit or financial gains specifically, and to date no corporate charters have been written that identify profit as one of those duties.

In the ordinary course of business, decisions made by a corporation's directors are generally protected by the business judgment rule, under which courts are reluctant to second-guess operating decisions made by directors. In a takeover or change of control situation, however, courts give less deference to directors' decisions and require that directors obtain the highest price in order to maximize shareholder value in the transaction. Thus a corporation may be unable to maintain its focus on social and environmental factors in a change of control situation because of the pressure to maximize shareholder value.

Mission-driven businesses, impact investors, and social entrepreneurs are constrained by this legal framework, which is not equipped to accommodate for-profit entities whose mission is central to their existence.

Even in states that have passed "constituency" statutes, which permit directors and officers of ordinary corporations to consider non-financial interests when making decisions, legal uncertainties make it difficult for mission-driven businesses to know when they are allowed to consider additional interests. Without clear case law, directors may still fear civil claims if they stray from their fiduciary duties to the owners of the business to maximize profit.[4]

By contrast, benefit corporations expand the fiduciary duty of directors to require them to consider non-financial stakeholders as well as the interests of shareholders.[31] This gives directors and officers of mission-driven businesses the legal protection to pursue an additional mission and consider additional stakeholders.[32][33] The enacting state's benefit corporation statutes are placed within existing state corporation codes so that the codes apply to benefit corporations in every respect except those explicit provisions unique to the benefit corporation form.

Provisions

[edit]Typical major provisions of a benefit corporation are:[34]

Purpose

- Shall create general public benefit.

- Shall have the right to name specific public benefit purposes

- The creation of public benefit is in the best interests of the benefit corporation.

Accountability

- Directors' duties are to make decisions in the best interests of the corporation

- Directors and officers shall consider effect of decisions on shareholders and employees, suppliers, customers, community, environment (together the "stakeholders")

Transparency

- Shall publish annual Benefit Report in accordance with recognized third party standards for defining, reporting, and assessing social and environmental performance

- Benefit Report delivered to: 1) all shareholders; and 2) public website with exclusion of proprietary data

Right of action

- Only shareholders and directors have right of action

- Right of action can be for 1) violation of or failure to pursue general or specific public benefit; 2) violation of duty or standard of conduct

Change of control/purpose/structure

- Shall require a minimum status vote which is a 2/3 vote in most states, but slightly higher in a few states

Benefit corporations are treated like all other corporations for tax purposes.[34]

Benefits

[edit]Benefit corporation laws address concerns held by entrepreneurs who wish to raise growth capital but fear losing control of the social or environmental mission of their business. In addition, the laws provide companies the ability to consider factors other than the highest purchase offer at the time of sale, in spite of the ruling on Revlon, Inc. v. MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings, Inc. Chartering as a benefit corporation also allows companies to distinguish themselves as businesses with a social conscience, and as one that aspires to a standard they consider higher than profit-maximization for shareholders.[35] Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia, has written "Benefit corporation legislation creates the legal framework to enable companies like Patagonia to stay mission-driven through succession, capital raises, and even changes in ownership, by institutionalizing the values, culture, processes, and high standards put in place by founding entrepreneurs."[36]

Oregon House Bill 3572, signed by the governor of Oregon in July 2023,[37] allows public contracting agencies to award contracts to benefit corporations if the goods and services are not more than 5% higher than the goods and services available from another company.[38]

Benefit corporation vs. certified benefit corporation

[edit]There is a difference between being filing as a benefit corporation in a state, and being a certified benefit corporation also known as a B Corporation. B Corporations voluntarily promise to run their firm with social and environmental causes as a concern.[39] To receive their certification from B Lab they must score a minimum of 80 out of 200 on a survey called the B impact assessment.[39] Next, they will have to pass through an audit process.[39] Finally, the firms wishing to remain certified will be required to pay an annual fee to B Lab.[39] Furthermore, companies will pledge to incorporate as a benefit corporation before their re-certification.[39]

Benefit corporations and cooperatives

[edit]Benefit corporations are not synonymous with cooperatives, which are a type of corporate governance in which the governance and shares are equally held by their members, such as all employees or all consumers. However, a benefit corporation may also be organized as a cooperative or vice versa.

Taxation

[edit]A public benefit corporation is a legal entity that is organized and taxed as either an S corporation or C corporation.[39] Founders will want to keep in mind that C-corporations experience a double tax associated with profits and again with dividends or payouts to shareholders.[40] S corporations are a legal entity that escapes this double taxation but there are certain stipulations that an entity will have to consider before being able to file as an S corporation.[40] If you are currently an S or C corporation your company will not change its tax status when you transfer to a public benefit corporation.[39] If you are currently an LLC, partnership or sole proprietorship then you will have to change tax status.[39] While public benefit corporations are taxed the same as their underlying corporation status, there is added benefit to taxation on charitable contributions. If a firm makes donations to a qualifying non-profit the charitable contributions receive a tax deductible status. This will lower a firm's taxes compared to a typical C-corporation that is not donating money and only focusing on short term profits.

Possible incentives to change to a benefit corporation

[edit]Reorganizing as a public benefit corporation affords a corporation's directors and founders protection from shareholder lawsuits when pursuing decisions that benefit the public at the expense of short-term profits.[39] Furthermore, firms that transition typically experience advantages in retaining employees, increasing their customer loyalty and attracting prospective talent that will mesh well into the company culture.[39]

Transition process

[edit]Changing status to a public benefit corporation requires several steps. First, the firm should choose one or more specific public benefit projects that it will pursue. Next, the articles of incorporation should be amended to state at the beginning that the firm is a public benefit corporation. The term public benefit corporation (PBC) or another abbreviation may be added to the entity's name if the founders choose. Finally the share certificates that are issued by the entity should state that the firm is a public benefit corporation. A shareholder vote is required to amend the articles which must include "non-voting" shares. The vote must gain a two-thirds majority to pass, depending on the Articles of Incorporation.[39] Shareholders should be notified early that dissenter's rights apply. Dissenter's rights mean that those that vote against the amendment and qualify, may require the company to buy back their shares at fair value before the change.[39] Firms making the transition should also perform a "due diligence review" of their business contracts, affairs and status in order to avoid any unforeseen liability associated with changing the form of the entity.[39]

The transition process is different state by state but for Colorado it is as follows. First, the firm must prepare the aforementioned amended articles. Then, they also amend their bylaws and assign responsibilities to the board of directors. Next, the amendments must be approved by the directors before going to a shareholder vote. Finally they file the amended articles of incorporation with the secretary of the state.[39]

If the prior entity is an LLC or partnership there is an extra step required. For these entities the articles of incorporation themselves and the related bylaws must first be prepared and filed with the state secretary. Only then will it be possible to merge or transition the previous form into the benefit corporation.[39]

Investor and consumer preferences

[edit]According to William Mitchell Law Review journal, about 68 million US customers have a preference for making decisions about their purchases based on a sense of environmental or social responsibility.[41] Some individuals even go as far as using their purchases to "punish" companies for bad corporate behavior when it pertains to environmental or social cause.[41] While others do the opposite, and use their purchasing power to reward firms that they believe are doing social or environmental good.[41] The Mitchell Law Review also states that around 49% of Americans have at some point in time boycotted firms whose behavior they see as "not in the best interest of society."[41] Recent research also suggests that when variables like price and quality are held constant, 87% of customers would switch from a less socially responsible brand to a more socially responsible competitor.[41]

See also

[edit]- B corporation (certification) – Social and environmental certification of for-profit companies

- Community interest company – UK company using their profits and assets for the public good

- Conscious business – Business concept

- Examples of Delaware benefit corporations (known legally as public benefit corporations or PBCs):

- Kickstarter – US-based crowdfunding platform

- Change.org – American petition website

- Flexible purpose corporation – California corporation pursuing a social benefit

- Green America – US non-profit organization

- Impact investing – Investing in enterprises aiming at creating social/environmental impact alongside profit

- Low-profit limited liability company – Legal form of business entity in the US

- Public-benefit nonprofit corporation – Chartered by a US state government

- Social enterprise – Type of organization

- Social purpose corporation – For-profit that enables, without requiring, social or environmental decision making

- Socially responsible investing – Any investment strategy combining both financial performance and social/ethical impact.

- Stakeholder theory – Management and ethical theory that considers multiple constituencies

- Sustainable business – Minimal negative or positive effect on the environment

- Workplace spirituality – Grassroots movement since early 1920s

References

[edit]- ^ Pearlstein, Steven (September 6, 2013). "Businesses' focus on maximizing shareholder value has numerous costs". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c Lee, Jaime (May 2018). "Benefit Corporations: A Proposal for Assessing Liability in Benefit Enforcement Proceedings". Cornell Law Review. 103 (4): 1075–1100. ISSN 0010-8847.

- ^ Bagley, Constance E. (2018). The Entrepreneur's Guide to Law & Strategy, fifth edition. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning, Inc. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-1-285-42849-9.

- ^ a b Kincaid, Amy; et al. (January 1, 2013). "Maryland Benefit Corporation Act: The State of Social Enterprise in Maryland". Slideshare. Retrieved October 9, 2019.

- ^ Murray, J. Haskell (2022). "Enforcing Benefit Corporation Reporting". Transactions: The Tennessee Journal of Business Law (23): 505.

- ^ "What is a Benefit Corporation?". www.nolo.com. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ a b "State by State Status of Legislation". B Lab. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ "Indiana Benefit Corporations: The What, How and Whether of Forming a B-Corp". Freitag & Martoglio. September 21, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Kurland, Nancy (2018). "ESOP plus benefit corporations: Ownership culture with benefit accountability". California Management Review. 60 (4): 51–73. doi:10.1177/0008125618778853. S2CID 158057120.

- ^ "Xconomy: Joining Trend, WI Creates New Business Entity: Benefit Corporations". Xconomy. November 2, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ "2023 Code of Alabama :: Title 10A - Alabama Business and Nonprofit Entities Code. :: Chapter 2A - Alabama Business Corporation Law. :: Article 17 - Benefit Corporations. :: Section 10A-2A-17.01 - Application of Article 17; Definitions". Justia Law. Retrieved May 24, 2024.

- ^ "Benefit Corporations vs Public Benefit Corporations in Iowa" Surge Business Law. "an Iowa 'benefit corporation' may have both a profit and public benefit motive while an Iowa 'public benefit corporation' is a charitable non-profit organization."

- ^ Stuart, Christine (October 1, 2014). "20 Connecticut Social Entrepreneurs Convert Their Companies to Benefit Corporations". CT News Junkie. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ^ S.B. 2358, 98th Gen. Assem. (Ill. 2013).

- ^ Six Month Report (PDF) (Report). Governor's Task Force on Social Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Enterprise. April 2013.

- ^ "Washington State Legislature". apps.leg.wa.gov.

- ^ "Social Purpose Corporation". Washington Secretary of State. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

As of June 7, 2012, a new type of profit corporation will exist in Washington. ..[T]his law...would allow a corporation's shareholders and directors to put a social purpose (such as saving the environment or saving the whales) above the purpose of making a profit.

- ^ Italian financial Act for 2016– L. nr. 208/2015

- ^ Daniel (December 22, 2015). "Italian Parliament approves Benefit Corporation legal status". Amsterdam, Netherlands: B Lab. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ "Disposizioni per la formazione del bilancio annuale e pluriennale dello Stato". Gazzetta Ufficiale (in Italian). Republic of Italy. December 30, 2015. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ "The Legacy of B Lab: Italy's Società Benefit | The ECCLblog". University of Edinburgh. March 31, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ "What are benefit corporations, the companies doing good for society – LifeGate". LifeGate (in Italian). July 1, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ "The Dark Side of Colombia's Benefit Corporation". Oxford Law Faculty. June 8, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ McKeen, Alex (May 2, 2018). "Provincial Green Party eyes making B.C. the first Canadian jurisdiction to recognize 'benefit corporations' | The Star". Toronto Star. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ "Benefit Company BC".

- ^ "Benefit companies in British Columbia | DLA Piper".

- ^ "Full Multi - Business Corporations Act".

- ^ Regulator of Community Interest Companies (2016). Office of the Regulator of Community Interest Companies: Information and guidance notes. Chapter 1: Introduction (PDF). Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy. p. 8.

- ^ "Balancing purpose and profit: Legal mechanisms to lock in social mission for "profit with purpose" businesses across the G8". Trust Law. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ^ "The Corporate Conscience – The American Interest". The American Interest. March 2, 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

- ^ Marc J. Lane (March 11, 2014). "Emerging Legal Forms Allow Social Entrepreneurs to Blend Mission And Profits". Triple Pundit.

- ^ Marc J. Lane. "Representing Corporate Officers and Directors". Aspen Publishers: Wolters Kluwer Law & Business. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ Marc J. Lane. "Social Enterprises: A New Business Form Driving Social Change". The Young Lawyer. Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ^ a b "Maryland First State in Union to Pass Benefit Corporation Legislation". CSRWire USA. April 14, 2010.

- ^ New-Economy Movement Archived August 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine article by Gar Alperovitz, also appeared in the June 13, 2011, edition of The Nation

- ^ "Benefit Corporation Update: Patagonia Passes B Impact Assessment, Improves Score to 116 - Patagonia". www.patagonia.com. October 24, 2014.

- ^ "HB 3572 Enrolled". Oregon State Legislature. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Krizanac, Antonija (November 14, 2023). "Building in 2024: Recent Oregon Legislative Changes Impacting the Construction Industry". Davis Wright Tremaine LLP. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o The Alliance Center. "What Is the Difference between a Certified B Corporation and a Public Benefit Corporation (PBC)?" The Alliance Center Organization, http://www.thealliancecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Benefit-Corporation-101-Reduced.pdf.

- ^ a b "S Corporations | Internal Revenue Service". www.irs.gov. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Babson, William H. Clark Jr. & Elizabeth K. "How Benefit Corporations Are Redefining the Purpose of Business Corporations." William Mitchell Law Review (2012): 818-842.

External links

[edit]- Social Enterprise Law Tracker – Interactive map visualizing the progression of benefit corporation legislation across the United States

- BenefitCorp.net Archived August 20, 2020, at the Wayback Machine – Information about creating and running benefit corporations

- Vermont benefit corporation statute – an example of legislation

- California benefit corporation statute