Harmonica techniques

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

There are numerous techniques available for playing the harmonica, including bending, overbending, and tongue blocking.

Bending and other techniques

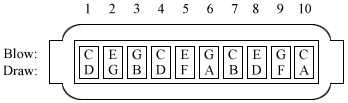

[edit]In addition to the 19 (draw 2 and blow 3 are the same pitch even though there are 10 holes) notes readily available on the diatonic harmonica, players can play other notes by adjusting their embouchure and forcing the reed to resonate at a different pitch. Although it is notoriously difficult and can be frustrating for beginners, one does this by relaxing and coordinating muscles in the throat, mouth, and lips. This technique is called "bending", a term borrowed from guitarists, who literally "bend" a string in order to create changes in pitch. Using bending, a player can reach all the notes on the chromatic scale. "Bending" also creates the glissando characteristic of much blues harp and country harmonica playing. Bending on a guitar bends the pitch upward. However, typically "bending" on a harmonica means the pitch falls downward. Bends are essential for most blues and rock harmonica due to the soulful sounds the instrument can bring out. The famous "wail" of the blues harp typically required bending.

|D |F |A♯| |B |D♯|F♯|B | hole: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 ----------------------------- blow: |C |E |G |C |E |G |C |E |G |C | draw: |D |G |B |D |F |A |B |D |F |A | ----------------------------- |C♯|F♯|A♯|C♯|E |G♯| |F |A | |G♯|

The physics of bending are quite complex, but amount to this: a player can bend the pitch of the higher-tuned reed down toward the pitch of the lower-tuned reed in any given hole. In other words, on holes 1 through 6, the draw notes can be bent and on holes 7 through 10 the blow notes can be bent. Hole 3 allows for the most dramatic bending: in C, it is possible to bend 3 draw from a B down to a G♯, or anywhere in between.

Overbending

[edit]In the 1970s, Howard Levy developed the "overbending" technique (also known as "overblowing" and "overdrawing"). Overbending, combined with bending, allowed players like Chris Michalek, Carlos del Junco, Otavio Castro and George Brooks to play the entire chromatic scale. When bending, the player forces the lower of the two reeds in a chamber to vibrate faster, while the higher pitched reed vibrates slower. When overbending, the player isolates the higher of the two reeds and by so doing can play higher pitched notes. By using both bending and overbending techniques a player can play the entire chromatic scale using a diatonic harmonica. This has allowed diatonic harmonica players to expand into areas traditionally viewed as inhospitable to the instrument such as jazz.

The overbend is a difficult technique to master. To facilitate overbending, many players use specially modified or customised harmonicas. Any harmonica can be set up for better overbending. The primary needs are tight tolerances between the reed and reed-plate and a general level of air-tightness between the reed-plate and comb. The former often necessitates lowering the "gap", the space between the tip of the reed and the reed-plate. Another often used technique called embossing is to make the space between the sides of the slots in the reed-plate and the reed itself as small as possible by drawing in the metal on the sides of the reed-plate slots towards the reed. While these modifications make the harmonica overbend more easily, overbending is often possible on stock diatonic harmonica, especially on an airtight design.

Overblows Blow-Bends

B♭

E♭ E♭ F♯ B♭ E♭ F♯ B

C E G C E G C E G C <= Blow

(1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6) (7)(8)(9)(10)

D G B D F A B D F A <= Draw

C♯ F♯ B♭ C♯ A♭ C♯ A♭ C♯

F A

A♭

Draw-bends Overdraws

Although there are players who use precise overbends and bends to play the diatonic harmonica as a fully chromatic instrument, this is still very rare, not simply because the technique is very difficult, but also because it requires an extreme level of skill, as well as a perfectly setup instrument, to match the tone of an overbend to the sound of other normally played notes. Thus, even though a player could play any melody in any key (within a three octave range) on a C diatonic harmonica, most harmonica players (especially those who focus on blues and/or diatonic harmonicas) prefer to match the possibilities of glissandos, register and dynamics of a given melody to a harmonica. Thus, the common practice is still to use different keys of diatonic harmonicas; recently some also use valved diatonics or XB-40 for different songs. As for harmonica players who play mostly classical or jazz music, most would rather use chromatics, as those styles call for a more fully chromatic style.

However, more and more people are attempting to overblow, or at least trying to bend on all notes (using valves or the XB-40), on diatonics, since overbend and bending allow wailing, which is a desired aspect of many styles such as blues – something that is hard to simulate with chromatic harmonicas.

The vibrato might also be achieved via rapid glottal (vocal fold) opening and closing, especially on draws (inhalation) simultaneous to bending, or without bending. This obviates the need for cupping and waving the hands around the instrument during play.

Tongue blocking and lip pursing

[edit]Tongue blocking and lip pursing are two different ways of playing the harmonica with one's mouth. Tongue Blocking is when you put your mouth over three or more holes on the harmonica but you cover all the holes but one with your tongue. This technique gives you the ability to play a variety of sounds. Lip Pursing is playing a single note by pursing the lips and covering only one hole. The Tongue Blocking Technique is used by Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson I (John Lee Williamson), Sonny Boy Williamson II (Aleck Ford "Rice" Miller), Big Walter Horton, James Cotton, George Smith, Taj Mahal, among many others. The Lip Pursing Technique is used by Paul Butterfield, Junior Wells, Sugar Blue, Stevie Wonder, Jason Ricci among many others.[1]

Positions

[edit]In addition to playing the diatonic harmonica in its original key, it is also possible to play it in other keys by playing in other "positions", using different keynotes. Using just the basic notes on the instrument would mean playing in a specific mode for each position (e.g. playing in D Dorian or G mixolydian on a C Major harmonica), but techniques such as bending enable different modes to be used at each position (e.g. playing in E mixolydian on a C Major harmonica). Harmonica players (especially blues players) have developed a set of terminology around different "positions" which can be somewhat confusing to other musicians. There are twelve "natural positions" (one for each semitone), numbered from 1st position as given (on a standard 10-hole diatonic) by the note on the 1 blow and going up round the cycle of 5ths - so on a C harp, 1st position gives C, 2nd position G, 3rd D, 4th A etc. With this numbering system, positions 7-11 (on a C instrument, those having keynotes F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯) are based on notes only available by bending or overblowing. The terminology of positions is also applicable to chromatic harmonicas.

The first three positions cover the vast majority of harmonica playing, and these positions have names as well as numbers. They are:

- 1st position (or "straight harp"): Ionian mode. Playing the harmonica as it was intended, in its main major key. On a diatonic, starting note is hole 1 blow. On a C-chromatic, starting hole is the same, resulting in C major scale. This is the main position used for playing folk music on the harmonica.

- 2nd position (or "cross harp"): Mixolydian mode. Playing the harmonica in a key a fourth below its intended key. Playing just the unbended notes, this position gives the mixolydian scale between 2 draw and 6 blow. However, bending the 3 draw allows the player to play a minor third (or a blue third), allowing a player to use a C harmonica to play in G mixolydian or G minor. Blues players can also play a tritone in this position by bending the 4 draw. See a more extensive discussion of this position at the article on blues harp. On a diatonic, starting note is hole 2 draw or hole 3 blow. On a C-chromatic, starting hole is hole 3 blow, resulting in G major with a flatted 7th.

- 3rd position (or "double cross harp" or "slant harp"): Dorian mode. Playing the harmonica a full tone above its intended key. This gives a dorian scale between 4 draw and 8 draw, though once again bends and overblows give players a variety of options. Blues players can achieve a tritone by bending the 6 draw. On a diatonic, starting hole is hole 1 draw. On a C-chromatic, starting hole is hole 1 draw, resulting in D-minor with a raised 6th. This is the traditional way of playing Blues on Chromatic.

The terminology for other positions is slightly more varied. It is possible, of course, to play in any of the modes and, using overblows and bends, it is possible to play in all 12 keys on a single diatonic harmonica, though this is very rarely done on a diatonic. Even if a player is capable of playing multiple keys on a single harmonica, they will usually switch harmonicas for different songs, choosing the right "position" for the right song so as to achieve the best sound. Even when the same notes can be achieved on a different key of harmonica, choosing different keys of harmonicas will offer a variety of options such as slides, bends, trills, overblows, overbends, and tongue splits. Breathing patterns are changed position to position, changing the difficulty of the transitions between one note to the next, and altering the ratio of blow notes and draw notes. The different starting place for each position limits or extends note options for the bottom and top octaves. Changing positions will allow the player to create a different sound overall.

Blues harp (2nd position)

[edit]Blues harp or cross harp denotes a playing technique that originated in the blues music culture, and refers to the diatonic harmonica itself, since this is the kind that is most commonly used to play blues. The traditional harmonica for blues playing was the Hohner Marine Band, which was affordable and easily obtainable in various keys even in the rural American South, and since its reeds could be "bent" (see below) without deteriorating at a too rapid rate.

A diatonic harmonica is designed to ease playing in one diatonic scale. Here is a standard diatonic harmonica's layout in the key of C (1 blow is middle C):

This layout easily allows the playing of notes most important in C major, that of the C major triad: C, E, and G. The tonic chord is played by blowing and the dominant chord is played by drawing.

Blues harp subverts the intention of this design with what is "perhaps the most striking example in all music of a thoroughly idiomatic technique that flatly contradicts everything that the instrument was designed for" (van der Merwe [2] p66), by making the "draw" notes the primary ones, since they are more easily bent (for holes 1-6) and consist (relative to the key of the harmonica) of II, V, VII, IV, and VI. In the case of a major C harmonica, this will be D, G, B, F, and A. This allows two things:

- Bending on the draw notes;

- An approximation of the blues scale, which consists of I, III♭, IV, V♭, V, VII♭. If played on a C-keyed harp, this produces a blues scale in G: G, B♭, C, D♭, D, F. (This resembles the tuning of the bottleneck guitar).

The player can play slurs or bends around the minor/major third of the scale and around the tritone/fifth of the scale, both of which are vital to many blues compositions. For a further discussion of "bending" on the harmonica, see the harmonica article.

The key played in this style is one fifth above the nominal tuning of the harmonica, e.g. a C harmonica is played in the key of G. Therefore, to be in tune with a normal guitar tuning of E, an A harmonica is often used. This is because by playing the C harmonica in G, or A harmonica in E, the dominant or seventh chord is produced in place of the tonic chord, and in the blues, all chords are typically played as dominant (seventh or ninth) chords.

This is playing in 2nd position, called "cross harp."

If we use a solo-tuned harmonica instead of richter-tuned, it will be in 3rd position, a ii-minor key. So in the case of a C harmonica, it will be in the key of D minor. This is called "slant harp." Minor keys can also be easily played in 4th and 5th positions.

Breaking-in a harmonica

[edit]Harmonica players disagree on the need to break-in the reeds of a new harmonica, and on break-in technique. Even among those that favor a break-in period, numerous techniques appear: some may prefer to play a new harmonica for several hours without bending notes; others prefer to play for many short periods of time with reasonable breaks in between, as recommended by acclaimed chromatic harmonica technician and player Douglas Tate. Some diatonic players use a 12 volt car vacuum to work the reeds, which is claimed to avoid premature stress cracks.

Although not generally recommended nowadays by either players or manufacturers, some past players have felt soaking their harmonicas in warm water, and even beer, whiskey, or vodka helped break them in, believing that this facilitates bending of the notes. This is done only with aged wood combed harmonicas; as the wood ages, it can shrink, and in the case of the Hohner Marine Band harmonica (or any harmonica with wooden parts) soaking causes the wood to swell and makes the instrument more airtight. The problem with this is that the wood has a tendency to swell and crack when it is soaked in any type of liquid.

References

[edit]- ^ "Harmonica Techniques: Lip Pursing Versus Tongue Blocking". Music.knoji.com. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ van der Merwe, Peter (1989) Origins of the Popular Style: The Antecedents of Twentieth-Century Popular Music, Clarendon Press, Oxford; ISBN 0-19-316121-4