Boudican revolt

| Boudican revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Roman conquest of Britain | |||||||

The Roman province of Britain (red), where the revolt took place. The Roman Empire is in white. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Empire |

Iceni Trinovantes Other Celtic Britons | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Gaius Suetonius Paulinus | Boudica | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 | 230,000 (Cassius Dio) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 400 | 80,000 (Cassius Dio) | ||||||

| 70,000–80,000 civilians killed[1][2] | |||||||

The Boudican revolt was an armed uprising by native Celtic Britons against the Roman Empire during the Roman conquest of Britain. It took place circa AD 60–61 in the Roman province of Britain, and it was led by Boudica, the Queen of the Iceni tribe. The uprising was motivated by the Romans' failure to honour an agreement they had made with Boudica's husband, Prasutagus, regarding the succession of his kingdom upon his death, and by the brutal mistreatment of Boudica and her daughters by the occupying Romans.

Although heavily outnumbered, the Roman army led by Gaius Suetonius Paulinus decisively defeated the allied tribes in a final battle which inflicted heavy losses on the Britons. The location of this battle is not known. It marked the end of resistance to Roman rule in most of the southern half of Great Britain, a period that lasted until AD 410.[3] Modern historians are dependent for information about the uprising and the defeat of Boudica on the narratives written by the Roman historians Tacitus and Dio Cassius, which are the only surviving accounts of the battle known to exist.[4]

Cause of the rebellion

[edit]In AD 43 Rome invaded south-eastern Britain.[5] The conquest was gradual, and while some native kingdoms were defeated in battle and occupied, others remained nominally independent as allies of the Roman empire.[6]

One such tribe was the Iceni in what is now Norfolk. Their king, Prasutagus, thought he had secured his independence by leaving his lands jointly to his daughters and to the Roman emperor, Nero, in his will. However, when he died, in 61 or shortly before, his will was ignored. Tacitus describes the Romans as seizing lands, enslaving Icenians and of violently humiliating his family; his widow, Boudica, was flogged and her daughters raped.[7][8] According to Dio, Roman financiers called in their loans.[9]

Initial rebel actions

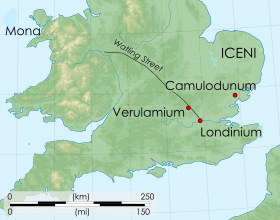

[edit]In AD 60 or 61, while the Roman governor, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, was leading a campaign against the island of Mona (modern Anglesey) off the northwest coast of Wales, a refuge for British rebels and a stronghold of the druids, the Iceni conspired with their neighbours the Trinovantes, amongst others, to rise in revolt.

Boudica was their leader. According to Tacitus, the rebels drew inspiration from the example of Arminius, the prince of the Cherusci who had driven the Romans out of Germany in AD 9, and their own ancestors who had driven Julius Caesar from Britain.[10] Cassius Dio says that at the outset Boudica employed a form of divination, releasing a hare from the folds of her dress and interpreting the direction in which it ran, and invoked Andraste, a British goddess of victory.

In an imaginary speech, the Roman historian Tacitus has Boudica addressing her army with these words: "It is not as a woman descended from noble ancestry, but as one of the people that I am avenging lost freedom, my scourged body, the outraged chastity of my daughters," and concludes, "This is a woman's resolve; as for men, they may live and be slaves."[11] Tacitus depicts Boudica as a victim of Roman slavery and licentiousness, her fight against which made her a champion of both barbarian and British liberty;[12] and he portrays Boudica's actions as an example of the bravery of a free woman, rather than of a queen, sparing her the negative connotations associated with queenship in the ancient world.[12]

Camulodunum

[edit]The first target of the rebels was the former capital of the Trinovantes, Camulodunum (Colchester), which had been made into a colonia for Roman military veterans. These veterans had been accused of mistreating the locals. A huge temple to the former emperor Claudius had also been erected in the city at great expense to the local population, causing much resentment.[13] The future governor Quintus Petillius Cerialis, then commanding the Legio IX Hispana, attempted to relieve the city, but suffered an overwhelming defeat. The infantry with him were all killed and only the commander and some of his cavalry escaped.[14] The location of this battle is unknown.[15]

The Roman inhabitants sought reinforcements from Catus Decianus, but he sent only two hundred auxiliary troops. Boudica's army attacked the poorly defended city and destroyed it, besieging the last defenders in the temple for two days before it fell. Archaeologists have shown that the city was methodically demolished.[16] After this disaster, Catus Decianus, whose actions had provoked the uprising, fled to Gaul.[8]

Londinium

[edit]When news of the rebellion reached Suetonius, he hurried through hostile territory to Londinium, a relatively new settlement founded after the conquest of AD 43, which had grown to be a thriving commercial centre with a population of traders and probably Roman officials. Suetonius considered fighting the rebellious tribes there, but with his insufficient numbers of troops and chastened by Petillius's defeat, he decided to sacrifice the city to save the province and withdrew to regroup his forces.

Alarmed by this disaster and by the fury of the province which he had goaded into war by his rapacity, the procurator Catus crossed over into Gaul. Suetonius, however, with wonderful resolution, marched amidst a hostile population to Londinium, which, though undistinguished by the name of a colony, was much frequented by a number of merchants and trading vessels. Uncertain whether he should choose it as a seat of war, as he looked round on his scanty force of soldiers, and remembered with what a serious warning the rashness of Petillius had been punished, he resolved to save the province at the cost of a single town. Nor did the tears and weeping of the people, as they implored his aid, deter him from giving the signal of departure and receiving into his army all who would go with him. Those who were chained to the spot by the weakness of their sex, or the infirmity of age, or the attractions of the place, were cut off by the enemy.— Tacitus

The wealthy citizens and traders of Londinium had fled after the news of Catus Decianus defecting to Gaul. Suetonius took with him as refugees those citizens who wished to escape, and the rest of the inhabitants were left to their fate.[17] The rebels burned Londinium, torturing and killing everyone who had not evacuated with Suetonius. Archaeology shows a thick red layer of burnt debris covering coins and pottery dating before AD 60 within the bounds of Roman Londinium;[18] Roman-era skulls found in the Walbrook in 2013 may have been victims of the rebels.[19] Excavations in 1995 revealed that the destruction extended across the River Thames to a suburb at the southern end of London Bridge.[20]

Verulamium

[edit]The municipium of Verulamium (modern St Albans) was also destroyed. Archeological evidence for this event is very limited. A major excavation by Mortimer Wheeler and his wife Tessa in the early 1930s found little trace of it, perhaps because they are now known to have been working away from the area which was settled in the early Roman occupation. Another excavation by Sheppard Frere between 1957 and 1961 revealed a row of shops alongside Watling Street which had been burned at around 60 AD, but the full extent of the destruction remains unclear. Excavations in the centre of Verulamium the 1996 extension dig before the new museum entrance was built, went through thin layers of burning from the time of the early Roman construction thought to be from the time. The thickest layer only 2 centimetres down to just a half a centimetre. [21]

Violence perpetrated on the Roman populations

[edit]In the three settlements destroyed, between seventy and eighty thousand people are said to have been killed. Tacitus says that the Britons had no interest in taking or selling prisoners, only in slaughter by gibbet, fire, or cross.[1] Dio's account gives more detail; that the noblest women were impaled on spikes and had their breasts cut off and sewn to their mouths, "to the accompaniment of sacrifices, banquets, and wanton behaviour" in sacred places, particularly the groves of Andraste.[2]

Final battle

[edit]Preparations by both sides

[edit]

While the Britons continued their destruction, Suetonius regrouped his forces. According to Tacitus, he amassed a force including his own Legio XIV Gemina, some vexillationes (detachments) of the XX Valeria Victrix, and any available auxiliaries.[22] The prefect of Legio II Augusta at Isca (Exeter), Poenius Postumus, did not obey an order to bring his troops,[23] but nonetheless Suetonius now commanded an army of almost 10,000 men.

At an unidentified location, Suetonius took a stand in a narrow passage with a wood behind him that opened out into a wide plain. His men were heavily outnumbered: Dio says that, even if they were lined up one deep, they would not have extended the length of Boudica's line. By now the rebel forces they faced were said to have numbered 230,000–300,000, although modern historians[who?] say these numbers should be treated with scepticism.[citation needed] The sides of the passage protected the Roman flanks from attack and the forest impeded approach from the rear. These precautions would have prevented Boudica from bringing her considerable forces to bear on the Roman position other than from the front, and the open plain would have made surprise attack impossible. Suetonius placed his legionaries in close order, with auxilia infantry on the flanks and cavalry on the wings.[24]

Although the Britons were gathered in considerable force, the Iceni and other tribes had been disarmed some years before the rebellion and it is thought they may have been poorly equipped.[4] They placed their wagons at the far end of the field, from where their families could watch what they may have expected to be an overwhelming victory.[22] Two Germanic leaders, Boiorix of the Cimbri and Ariovistus of the Suebi, are reported to have done the same thing in their battles against Gaius Marius and Caesar, respectively.[25]

As their armies deployed, the leaders would have sought to motivate their soldiers. Tacitus, who described the battle more than 50 years later, imagined Boudica's speech to her followers:

'But now,' she said, 'it is not as a woman descended from noble ancestry, but as one of the people that I am avenging lost freedom, my scourged body, the outraged chastity of my daughters. Roman lust has gone so far that not our very persons, nor even age or virginity, are left unpolluted. But heaven is on the side of a righteous vengeance; a legion which dared to fight has perished; the rest are hiding themselves in their camp, or are thinking anxiously of flight. They will not sustain even the din and the shout of so many thousands, much less our charge and our blows. If you weigh well the strength of the armies, and the causes of the war, you will see that in this battle you must conquer or die. This is a woman's resolve; as for men, they may live and be slaves.'[11]

Tacitus also wrote of Suetonius addressing his legionaries. Although, like many historians of his day, he was given to inventing stirring speeches for such occasions, Suetonius's speech here is unusually blunt and practical. Tacitus's father-in-law, the future governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola, was on Suetonius's staff at the time and may have reported it fairly accurately.[26]

Ignore the racket made by these savages. There are more women than men in their ranks. They are not soldiers — they are not even properly equipped. We have beaten them before and when they see our weapons and feel our spirit, they will crack. Stick together. Throw the javelins, then push forward: knock them down with your shields and finish them off with your swords. Forget about plunder. Just win and you will have everything.[27]

Defeat of Boudica

[edit]

Boudica is imagined by Tacitus, her daughters beside her, encouraging her troops with a stirring speech from her chariot.[11] After providing a speech to the Roman troops by Suetonius, Tacitus describes the battle:

At first, the legionaries stood motionless, keeping to the defile as a natural protection: then, when the closer advance of the enemy had enabled them to exhaust their missiles with certitude of aim, they dashed forward in a wedge-like formation. The auxiliaries charged in the same style; and the cavalry, with lances extended, broke a way through any parties of resolute men whom they encountered. The remainder took to flight, although escape was difficult, as the cordon of wagons had blocked the outlets. The troops gave no quarter even to the women: the baggage animals themselves had been speared and added to the pile of bodies. The glory won in the course of the day was remarkable, and equal to that of our older victories: for, by some accounts, little less than eighty thousand Britons fell, at a cost of some four hundred Romans killed and a not much greater number of wounded.[23]

The figures quoted for the campaign in ancient sources are regarded by modern historians as extravagant.[4][28] The Roman slaughter of women and animals was unusual, as they could have been sold for profit.[29]

Poenius Postumus, whose legion had not marched to join the battle, and were thus robbed of a share of the glory, killed himself by falling on his sword.[23]

Boudica's death

[edit]After the battle, Boudica is said by Tacitus to have poisoned herself,[23] though in the Agricola, which was written almost twenty years before the Annals, he mentions nothing of suicide and attributes the end of the revolt to socordia ("complacency").[30] Cassius Dio says Boudica fell ill, died and was given a lavish burial.[31]

Boudica's burial site is unknown, and is presumably somewhere in the south of Great Britain. Modern speculations about its location lack serious evidence and have not gained consensus among archaeologists or historians.[32][33] One local tradition has associated it with Gop Hill Cairn at Trelawnyd in Flintshire, Wales. The imaginative Morien suggests that Bryn Sion in Flintshire may have been the location where Boudica died.[34] Another legend suggests that she is buried under Platform 10 of London King's Cross railway station.[35]

Aftermath

[edit]The historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus writes that the crisis had almost persuaded Nero to abandon Britain,[36] but with the revolt brought to a decisive end, the occupation of Britain continued. Fearing that Suetonius's punitive actions against the British tribes would provoke further rebellion, Nero replaced him with the more conciliatory Publius Petronius Turpilianus.[37]

While the defeat of Boudica consolidated Roman rule in southern Britain, northern Britain remained volatile. In AD 69 Venutius, a Brigantes noble, was to lead another less well documented revolt, initially inspired by tribal rivalry but soon becoming anti-Roman.[38]

Catus Decianus, who had fled to Gaul, was replaced by Gaius Julius Alpinus Classicianus. After the uprising, Suetonius conducted widespread punitive operations among the Britons, but criticism of this by Classicianus led to an investigation headed by Nero's freedman Polyclitus.[39] No historical records tell what had happened to Boudica's two daughters.

Location of final battle

[edit]The site of the battle was not identified by either classical historian, although Tacitus mentions some of its features;[23] its location is unknown.[40] Most modern historians favour potential location sites in the Midlands, possibly along the Roman road between Londinium and Viroconium (Wroxeter) which became Watling Street.[41]

A site near Manduessedum (Mancetter), near the modern town of Atherstone in Warwickshire, was suggested by archaeologist Graham Webster.[42] Kevin K. Carroll suggests a site close to High Cross, Leicestershire, at the junction of Watling Street and the Fosse Way, which would have allowed the Legio II Augusta at Exeter to rendezvous with the rest of Suetonius's forces if they had come as ordered.[43]

Also suggested has been a site near Virginia Water in Surrey, between Callow Hill and Knowle Hill, off the Devil's Highway[44]

Local legends offer "The Rampart" near Messing, Essex and Ambresbury Banks in Epping Forest, although these accounts are not thought to hold a factual basis.[45] More recently, a discovery of Roman artefacts in Kings Norton close to Metchley Camp has suggested another possibility.[46] Considering Akeman Street as a possible route from the south-west, the Cuttle Mill area near Paulerspury and Church Stowe in Northamptonshire, have been suggested as a site for the battle.[47][48] In 2009, it was suggested that the Iceni may have been returning to their lands in Norfolk along the Icknield Way and encountered the Roman army in the vicinity of Arbury Banks, Hertfordshire.[49]

The area of King's Cross, London was previously a village known as Battle Bridge, an ancient crossing of the River Fleet. The original name of the bridge was Broad Ford Bridge. The name "Battle Bridge" led to a tradition that this was the site of a major battle between the Romans and the Iceni tribe led by Boudica,[50] but this tradition is not supported by any historical evidence and is rejected by modern historians, although Lewis Spence's 1937 book Boadicea – warrior queen of the Britons went so far as to include a map showing the positions of the opposing armies.[51]

A travel writer in the 18th century, Thomas Pennant, suggested that a hill named "Bryn Paulin", on which the north Wales town of St Asaph stood, may have been so called because Paulinus and his troops had made a camp on their way to or from Mona (Anglesey).[52] A later writer, Richard Williams Morgan, described as "patriotically fanatical, a man who drew creative inspiration from his inexhaustible capacity for self-deception", imaginatively "turned a collection of unrelated local landmarks" in this area "into the narrative of a desperate battle", in which, among other details, he cited as evidence a "Stone of the Grave of Vuddig".[52] Boudica's last battle has also been placed on the Wyddelian road at Trelawnyd (previously Newmarket) in Flintshire.[53][54] Morien suggests that Boudica was supported by Celts who were enraged at the killing of druids on Mona and moved towards the Roman force in North Wales, with battle possibly ensuing at Trelawnyd.[34]

Relics

[edit]A bronze head found in Suffolk in 1907, now in the British Museum, was probably struck from a statue of Nero during the revolt.[55]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Tacitus, Annals 14.33

- ^ a b Henshall, K. (2008). Folly and Fortune in Early British History: From Caesar to the Normans. Springer. p. 55. ISBN 978-0230583795.

- ^ Webster, Graham (1978). Boudica the British revolt against Rome AD 60. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415226066.

- ^ a b c Bulst, Christoph M. (October 1961). "The Revolt of Queen Boudicca in A.D. 60". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 10 (4): 496–509. JSTOR 4434717.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 19–22

- ^ Tacitus, Agricola 14

- ^ Tacitus Annals 14.31

- ^ a b Bowman, Alan K.; et al., eds. (1996). The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C. - A.D. 69: The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 509. ISBN 9780521264303.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 62.2

- ^ Tacitus, Agricola 15

- ^ a b c Tacitus Annals 14.35

- ^ a b Braund, David (1996). Ruling Roman Britain. London: Routledge. p. 132.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals 14.31–32

- ^ Tacitus, Annals 14.32

- ^ "Haverhill From the Iron Age to 1899". St. Edmundsbury Borough Council. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Jason Burke (3 December 2000). "Dig uncovers Boudicca's brutal streak". The Observer. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ Webster, Graham. Boudica, the British Revolt against Rome A.D. 60. Totowa: Rowman and Littlefield. pp. 93–94.

- ^ George Patrick Welch (1963). Britannia: The Roman Conquest & Occupation of Britain. p. 107.

- ^ Maev Kennedy (2 October 2013). "Roman skulls found during Crossrail dig in London may be Boudicca victims". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Muir, Hazel (21 October 1995). "Boudicca rampaged through the streets of south London". www.newscientist.com. New Scientist Ltd. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ Hingley & Unwin 2004, p. 180

- ^ a b Tacitus, Annals 14.34

- ^ a b c d e Tacitus, Annals 14.37

- ^ Tacitus, Annals 14.32

- ^ Florus, Epitome of Roman History 1.38; Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 1.51

- ^ Cassius Dio (Roman History 9-11) gives Suetonius a quite different speech.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals 14.36

- ^ Townend, G. B. (1964). "Some Rhetorical Battle-Pictures in Dio". Hermes. 92 (4): 479–80.

- ^ Goldsworthy, Adrian Keith (2016). Pax Romana : war, peace, and conquest in the Roman world. New Haven. ISBN 978-0-300-17882-1. OCLC 941874968.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Santoro L'Hoir, Francesca (2006). Tragedy, rhetoric, and the historiography of Tacitus' Annales. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan press. p. 115. ISBN 9780472115198.

- ^ Dio, Cassius. History of Rome. Vol. VIII. Translated by Cary, Earnest. Chicago: Loeb Classical Library. p. 105. OCLC 655792369.

- ^ Goucher, Candice (24 January 2022). Women Who Changed the World: Their Lives, Challenges, and Accomplishments through History [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-4408-6825-2.

- ^ Live, North Wales (2 May 2004). "Bring Boudicca back to Wales". North Wales Live. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ a b Vandrei, Martha (2018). Queen Boudica and Historical Culture in Britain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-881672-0.

- ^ Greenwood, Douglas (15 July 1999). "Historical Notes: Boadicea's bones under Platform 10". The Independent. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Suetonius, Nero 18, 39–40

- ^ Tacitus, Annals 38–39

- ^ Tacitus, Histories, 3.45

- ^ "Bodicea Queen of the Iceni". Retrieved 9 January 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "BBC – History – Boudicca". Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ Hughes, Margaret (29 June 2013). On Boudica's trail: possible sites for Boudica's last battle. On Boudica's Trail. University of Warwick. p. 34.

- ^ Sheppard Frere (1987). Britannia: A History of Roman Britain. p. 73.

- ^ Kevin K. Carroll (1979). "The Date of Boudicca's Revolt". Britannia. 10: 197–202. doi:10.2307/526056. JSTOR 526056. S2CID 164078824.

- ^ Fuentes, Nicholas (1983). "Boudicca Revisited". London Archaeologist. 4 (12): 311–317.

- ^ Antiquarian B. H. Cowper speculates that the name Ambresbury Banks derives from the legendary Ambrosius Aurelianus, a fifth-century hero, and thus impossible to link with the fate of Boudica: Cowper, Benjamin Harris (1876). "Ancient Earthworks in Epping Forest". The Archaeological Journal. 33: 246–248.

- ^ "Is Boudicca buried in Birmingham?". BBC News Online. 25 May 2006. Retrieved 9 September 2006.

- ^ British History Online, Paulerspury pp. 111–117, last paragraph. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol4/pp111-117

- ^ Pegg, John. "Battle_Church_Stowe_CP1".

- ^ Grahame Appleby (2009). "The Boudican Revolt: Countdown to Defeat". Hertfordshire Archaeology and History. 16: 57–66. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Walter Thornbury (1878). "Highbury, Upper Holloway and King's Cross". Old and New London: Volume 2. British History Online. pp. 273–279. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Spence, Lewis (1937). Boadicea, warrior queen of the Britons. London: Robert Hale. pp. 249–251. OCLC 644856428.

- ^ a b Williams, Carolyn D. (2009). Boudica and Her Stories: Narrative Transformations of a Warrior Queen. University of Delaware Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-87413-079-9.

- ^ Morgan, R. W. (24 June 2022). St. Paul in Britain. BoD – Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-375-06741-0.

- ^ Parry, Edward (1851). Royal visits and progresses to Wales, and the border counties.

- ^ Russell, Miles; Manley, Harry (2013). "A case of mistaken identity? Laser-scanning the bronze "Claudius" from near Saxmundham" (PDF). Journal of Roman Archaeology. 26 (26): 393–408. doi:10.1017/S1047759413000214. S2CID 193197188.

[…]the balance of probability is that this provincial bronze statue of Rome's fifth emperor was toppled and decapitated during the Boudiccan Revolt of 60/61

External links

[edit]- Boudica

- 60s in the Roman Empire

- 60s conflicts

- 1st-century rebellions

- 1st century in Roman Britain

- Iceni

- Rebellions against the Roman Empire

- Women in 1st-century warfare

- Women in ancient European warfare

- Women in war in Britain

- Wars involving the Roman Empire

- 1st century

- Battles involving the Britons

- Battles involving the Roman Empire

- Military history of Roman Britain

- 1st-century battles