Battles of Rzhev

| Battles of Rzhev | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Total: 3,680,300[Note 1] | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Location within modern-day Russia | |||||||||

The Battles of Rzhev (Russian: Ржевская битва, romanized: Rzhevskaya bitva) were a series of Red Army offensives against the Wehrmacht between 8 January 1942 and 31 March 1943, on the Eastern Front of World War II. The battles took place in the northeast of Smolensk Oblast and the south of Tver Oblast, in and around the salient surrounding Rzhev. Due to the high losses suffered by the Red Army, the campaign became known by veterans and historians as the "Rzhev Meat Grinder" (Russian: Ржевская мясорубка, romanized: Rzhevskaya myasorubka).

Overview

[edit]The major operations that were executed in this area of the front were:

- Rzhev–Vyazma strategic offensive operation (8 January – 20 April 1942) of the Kalinin Front, Western Front, Bryansk Front, and Northwestern Front

- Sychyovka–Vyazma offensive operation (8 January – 20 April 1942) of the Kalinin Front

- Mozhaysk–Vyazma offensive operation (Operation Jupiter) (10 January – 28 February 1942) of the Western Front

- Toropets–Kholm offensive operation (9 January – 6 February 1942) of the Northwestern Front and reassigned to the Kalinin Front from 22 January 1942

- Vyazma airborne operation (18 January – 28 February 1942) of the Western Front (see also Operation Hannover)

- Rzhev–Vyazma offensive (1942) (3 March – 20 April 1942)

- Operation Seydlitz and the Soviet defensive battles around Bely and Kholm-Zhirkovsky (2–23 July 1942) launched by 9th Army of Germany to eliminate the salient in the vicinity between Bely and Kholm–Zhirkovsky and annihilate the 39th Army and 11th Cavalry Corps of the Kalinin Front[6]

- First Rzhev–Sychyovka offensive operation (30 July – 23 August 1942), (other sources say ending on 30 September or 1 October 1942) by forces of the Kalinin Front and Western Front

- Second Rzhev–Sychyovka offensive operation (Operation Mars) (25 November – 20 December 1942) by the forces of the Kalinin Front and Western Front

- Battle for Velikiye Luki (24 November 1942 – 20 January 1943) by 3rd Shock Army of the Kalinin Front

- Rzhev–Vyazma offensive (1943) (2–31 March 1943) by the forces of the Kalinin Front and Western Front, at the same time, the southern flank offensive operations on the Bryansk Front. These operations occurred during the planned German retreat from the salient known as Operation Büffel

Rzhev–Vyazma strategic offensive operation

[edit]During the Soviet winter counter-offensive of 1941, and the Rzhev–Vyazma strategic offensive operation (8 January 1942 – 20 April 1942), German forces were pushed back from Moscow. As a result, a salient was formed along the front line in the direction of the capital, which became known as the Rzhev–Vyazma salient. It was strategically important for the German Army Group Centre due to the threat it posed to Moscow, and was therefore heavily fortified and strongly defended.

Initial Soviet forces committed by the Kalinin and Western Front included the 22nd, 29th, 30th, 31st, 39th of the former, and the 1st Shock, 5th, 10th, 16th, 20th, 33rd, 43rd, 49th, and 50th armies and three cavalry corps for the latter. The intent was for the 22nd, 29th, and 39th Armies supported by the 11th Cavalry Corps to attack west of Rzhev, and penetrate deep into the western flank of Army Group Centre's 9th Army. This was achieved in January, and by the end of the month the cavalry corps found itself 110 km into the depth of the German flank. To eliminate this threat to the 9th Army's rear, the Germans had started Operation Seydlitz by 2 July. However, due to the nature of the terrain the supply route for the Soviet 22nd, 29th, and 39th Armies, which had attempted to enlarge the penetration, became difficult and they were encircled. The cutting of a major highway to Rzhev by the cavalry signalled the commencement of the Toropets–Kholm offensive.

Sychyovka–Vyazma offensive

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2017) |

The offensive was conducted in late 1942.

Mozhaysk–Vyazma offensive

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2017) |

Toropets–Kholm offensive

[edit]This offensive was conducted across the northern part of the Western Front against the Wehrmacht's 16th Army and 9th Army.

Vyazma airborne operation

[edit]A Soviet airborne operation, conducted by the 4th Airborne Corps in seven separate landing zones, five of them intended to cut major road and rail lines of communication to the Wehrmacht's 9th Army.

Operation Seydlitz

[edit]

In the aftermath of the Soviet winter counteroffensive of 1941–1942, substantial Soviet forces remained in the rear of the German Ninth Army. These forces maintained a hold on the primitive forested swamp region between Rzhev and Bely. On 2 July 1942, the Ninth Army under General Walter Model launched Operation Seydlitz to clear the Soviet forces out. The Germans first blocked the natural breakout route through the Obsha valley and then split the Soviet forces into two isolated pockets. The battle lasted eleven days and ended with the elimination of the encircled Soviet forces.

First Rzhev–Sychyovka offensive operation

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2017) |

Second Rzhev–Sychyovka strategic offensive (Operation Mars)

[edit]The next Rzhev–Sychyovka offensive (25 November 1942 – 20 December 1942) was codenamed Operation Mars. The operation consisted of several incremental offensive phases:

- Sychevka offensive 24 November 1942 – 14 December 1942

- Belyi offensive 25 November 1942 – 16 December 1942

- Luchesa offensive 25 November 1942 – 11 December 1942

- Molodoi Tud offensive 25 November 1942 – 23 December 1942

- Velikiye Luki offensive 24 November 1942 – 20 January 1943

This operation was nearly as heavy in losses for the Red Army as the first offensive, and also failed to reach its desired objectives, but the Red Army tied down German forces which may have otherwise been used to try to relieve the Stalingrad garrison. An NKVD double agent known as Heine provided information about the offensive to the German Army High Command as part of the plan to divert German forces from any relief of those trapped at Stalingrad.[7]

German forces in the salient were eventually withdrawn by Hitler during Operation Büffel to provide greater force for the German offensive operation at Kursk.

Rzhev–Vyazma offensive (1943)

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2017) |

Results

[edit]Politico-military result

[edit]

Fighting in the area remained mostly static for 14 months. Losses and setbacks elsewhere along the front finally compelled the Germans to abandon the salient in order to free up reserves for the front as a whole.

Defending the salient required 29 divisions. Its abandonment freed up 22 of those divisions and created a strategic reserve which allowed the Germans to stabilize the front and somewhat recover from massive losses at Stalingrad.

German General Heinz Guderian had doubts about the strategic aims of the later Operation Citadel, since the Germans had to abandon the strategically important Rzhev–Vyazma salient for gathering troops to attempt to take a much less valuable one at Kursk.[8] The retreat of the Germans in Operation Büffel was tactically and militarily successful, but the abandonment of the "Rzhev–Vyazma pistol" was a strategic loss for Nazi Germany on the Eastern Front.[9]

The Soviet Army paid a high price for their victory at Rzhev, but the Germans were forced to withdraw from an important bridgehead which had enabled the Germans to threaten Moscow. The Germans, however, retreated to defensive positions that were as strong as the ones they held within the salients, contributing to the failure of Red Army offensives against Army Group Center in the summer of 1943.[10]

Military losses

[edit]Losses for the entire series of operations around the Rzhev salient from 1941 to 1943 are difficult to calculate. These operations cover an entire series of battles and defensive operations over a wide area involving many formations on both sides.

For the whole series of Rzhev battles, the numbers are not clear. But, since the mobilized manpower of both sides was enormous and the fighting was violent, casualties would be expected to be very high. According to A. V. Isayev, the Soviet losses from January 1942 to March 1943 were 392,554 irrecoverable casualties (killed, missing, died before hospitalisation) and 768,233 sanitary (medical) casualties.[4] The Soviet losses during the beginning period of 1942 (including "Operation Jupiter") were 272,320 irrecoverable and 504,569 sanitary; with 25.7% of the total manpower that participated in these battles being killed on the battlefield.[11] According to V. V. Beshanov, the casualties of the July–September Rzhev offensive were 193,683 overall,[12] and during Operation Mars the Soviets suffered 250,000 casualties with 800 tanks damaged or destroyed.[12] Isayev provided a somewhat lower number: 70,340 irrecoverable and 145,300 sanitary casualties.[13]

Russian historian Svetlana Gerasimova states that the official Soviet casualty count of 1,324,823 men for the four offensive operations against the Rzhev-Vyazma salient only accounts for approximately 8 out of the 15 months of fighting.[14] Soviet operational losses from May–July and October–November 1942, and January–February 1943 are missing and not included in the official figure.[15] Gerasimova states that with the inclusion of casualties from these seven months, and the official casualty figures of the four offensive operations, the total losses approach 2,300,000 men.[16]

Retired German General Horst Grossmann did not provide the total casualties of the German side in his book Rzhev, the basement of the Eastern Front. According to his description, from 31 July to 9 August, one German battalion at the front line, after being exhausted in the violent battles, only had one commandant and 22 soldiers, and by 31 August there were battalions which had only one commandant and 12 soldiers (equal to one squad). According to Grossmann, during Operation Mars, the Germans suffered 40,000 casualties.[17]

According to German reports, which are still stored at the Storage Center of National Documents of Germany, from March 1942 to March 1943 the casualties of the 2nd, 4th, 9th, 2nd Panzer, 3rd Panzer and 4th Panzer Armies (the latter only having data from March to April 1942) amount to 162,713 killed, 35,650 missing, and 469,747 wounded.[18][19] However, according to Gerasimova, German casualties in the battle for Rzhev–Vyazma are uncertain, and the commonly cited 350,000–400,000 range lacks substantiation and references to documentary sources.[20] The number of soldiers that died during hospital treatment is still unknown.

Civilian losses

[edit]

Before the war, Rzhev had more than 56,000 people, but when it was liberated on 3 March 1943, there were only 150 people remaining, plus 200 in the surrounding rural area. The inhabitants were transported to Germany and Eastern Europe.[citation needed] Out of 5,443 houses, only 297 remained. Material losses were estimated at 500 million rubles (1941 value).[21]

Vyazma was also virtually destroyed during the war. In the city, two transit camps of Nazi Germany named Dulag No. 184 and Dulag No. 230 were established. Prisoners in these camps were Soviet soldiers and civilians from the area of Smolensk, Nelidovo, Rzhev, Zubtsov, Gzhatsk, and Sychyovka.[22] According to German data collected by the Soviet counter-espionage agency SMERSH, 5,500 people died of their wounds. During the winter of 1941–1942, in these camps, about 300 people each day were killed by diseases, cold, starvation, torture and other causes. After the war, two mass graves were discovered in the area, each 4 by 100 m in area and in total containing an estimated 70,000 bodies, all of them unidentified.[23] Germans also discovered and executed 8 local political leaders, 60 commissars and political instructors, and 117 Jews at Dulag camp 230.[24]

Evaluation of Soviet and German tactics

[edit]USSR

[edit]Strength

[edit]The Soviets managed to exploit the earlier victory at the Battle of Stalingrad and create some advantages in the critical sector of the front. Their attacks threatened the flanks of Army Group Center and forced the Germans to divert the forces to these areas, therefore reducing the pressure on Moscow. During this time, the USSR's Army commanders began to concentrate their main forces at the critical zones to strengthen their position in these areas, or to muster enough power for their assaults. In addition, the Soviets also started using tanks as a main assault force instead of a mere supporting tool for infantry.[25] The Front commanders also got some important experience in commanding and coordinating a combined force. From May 1942, Soviet Fronts started to deploy their own air armies for supporting the land troops, reporting under the direct command of the Front commanders. Thus these commanders began to have some sort of full authority to use the air forces, except the long-ranged strategic bomber units which were still under direct command of the Soviet Stavka.[26]

After the "manpower crisis" of late 1941, in 1942 the Soviets had gathered enough strategic reserves, and they also began to pay more attention to developing them. In 1942 the Soviets managed to build 18 new reserve armies and resupply 9 others. At Rzhev, the army received 3 reserve armies and had 3 others resupplied. Of course, in this period, many Soviet units still had inadequate strength and equipment, but with the more plentiful reserve force, they managed to somewhat maintain stable fighting capability and prevent the severe fluctuation in manpower. This enabled the Red Army to conduct active defenses and prepare for large-scaled offensives.[27]

Weakness

[edit]As the second highest ranking member of the Stavka, Marshal Georgy Zhukov was one of the first Soviet military officers to admit and to make a strict self-criticism about the Red Army and also his own faults in this period:

Today, after reflecting the events of 1942, I see that I had many shortcomings in evaluating the situation at Vyazma. We overestimated ourselves and underestimated the enemies. The "walnut" there was much stronger than what we predicted.

— G. K. Zhukov[27]

The Soviet Army suffered terribly from severe deficits in weapons and equipment due to the tremendous losses during the German onslaught in 1941. During the first half of 1942 the reserve sources of equipment were still inadequate. For example, during January and February 1942, the Western Front only received 55% of the needed 82 mm mortar rounds, 36% of needed 120 mm rounds and 44% of needed artillery munitions. On average, each artillery battery only had 2 rounds per day. The weapons deficit was so severe that the Front commanders had to make occasional appeals for equipment.[28][failed verification] The serious lack of ammunition hampered Soviet efforts in neutralizing German strongpoints, leading to heavy casualties in the assaults.[27]

The lack of munitions did not only occur in the case of cannons and mortars, but also for small arms. During the "ammunitions famine" at Rzhev salient, on average, the Red Army only had 3 bullets for each rifle, 30 bullets for each submachine gun, 300 bullets for each light machine gun and 600 bullets for each heavy one.[citation needed] The "famine" of munitions in firearms and artillery pieces forced the Soviet army commanders, in many cases, to use tanks in the role of artillery; such inappropriate usage together with outdated military thinking (which did not pay enough attention to the assault role of tank forces) sharply reduced the effectiveness of the tank units, preventing them from conducting deep penetration into the German defensive line.[29] For the tank forces, although the Soviet possessed a large number of tanks, the numbers of low quality, damaged and outdated ones were also large. In the Bryansk, Western and Kalinin Front, the proportion of low quality tanks was 69% and the rates of damaged tanks about 41-55%. All the above facts meant that the Red Army in the Rzhev area did not have adequate preparation in terms of equipment, weapons and logistics.

The worst mistakes of the Red Army in 1942 at the Rzhev salients lies in the coordination and cooperation between its Fronts and the control of Stavka towards them. During the offensives in January and February 1942, instead of establishing a centralized command and control with tight cooperation between the Fronts, the Soviet Stavka and I. V. Stalin let each Front carry out their own assault without notable cooperation between the Fronts. Such separated and uncooperative assaults failed to achieve their goals and lead to the total failure of the whole offensives. To make matters worse, on 19 January 1942 Stalin suddenly retook the 1st Shock Army from the Western Front with a "very nonsense" reason. That unreasonable act severely weakened the right wing of the Western Front and lead to the failure of the offensive at the area Olenino–Rzhev–Osuga.[30]

Further errors in the Soviet tactics and commands were the ambitious and unrealistic goals of the offensives. Early 1942, the Red Army had just recovered from the disastrous losses during the late half of 1941, therefore it was still very weak. In every offensive, the aims and scale have to be correlative with the army's strength, but at the battles of Rzhev, the Soviet commanders demanded too much from their subordinates.[31]

Last but not least, another "palindromic disease" of the Red Army in 1942 is the hesitation in retreating from threatened sectors. As a results, many Soviet units were trapped in a notable number of "pockets" when the Germans counter-attacked. In these cases, only the troops of 11th Cavalry Corps and 6th Tank Corps managed to escape successfully.[32] The escape of 33rd and 41st Army was conducted on time, but they failed to keep it secret and chose the wrong direction to move, leading to considerable casualties. And in the case of 11th Cavalry and 39th Army, the Stavka made a serious mistake when they planned to keep them in the Kholm-Zhirkovsky bridgehead for future attacks; however not only they failed to conduct any attacks but also they were surrounded and nearly destroyed during the Seydlitz operation.[4]

Germany

[edit]Strength

[edit]After the Soviet winter counter-offensive of 1941–42, the Germans were able to securely hold and defend the salient against a series of large Soviet offensives. The operations led to disproportionately high Soviet losses and tied down large numbers of Soviet troops. The defense of the Salient provided the Germans with a base from which they could launch a new offensive against Moscow at a future time. The defensive positions created by the Germans after the retreat from Moscow were well constructed and placed. The Germans eventually withdrew from the positions only due to losses elsewhere in the war and were able to withdraw from the salient with minimal losses.

Weakness

[edit]German operations in 1941 directed at Moscow lasted too late into the year. Rather than stabilize the front and create defensive positions, the Germans pushed their forces forward and left them poorly prepared for the Soviet winter counteroffensive. The losses in men and equipment to Army Group Centre were considerable. The Army group lacked the strength to go back on the offensive in 1942.

After the front stabilized, the German Army tied down enormous amounts of manpower in holding salients from which they did not intend to exploit. This reduced the amount of manpower the Germans could devote to operations elsewhere on the front. The Germans also used some of their best formations, such as 9th Army, in a strictly static defensive role. The Rzhev salient had value and tied down disproportionate numbers of Soviet troops, but it is unclear if the salient was worth the loss of around 20 high quality divisions for offensive or defensive operations elsewhere in 1942.

The abandonment of the salient was necessary in 1943 to create reserves for the front as a whole. But the reserves and the strength created were mostly used up in the costly offensive directed at Kursk in 1943 (Operation Citadel).

Controversies about the battles of Rzhev

[edit]This part of the Second World War was poorly covered by Soviet military historiography, and what coverage exists occurred only after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when historians gained access to relevant documents. Exact dates of particular battles, their names, outcomes, significance, and even losses have not been fully clarified and there are still many controversies about these topics.

Casualties of the Soviet forces

[edit]In 2009, a television movie was aired in Russia entitled Rzhev: Marshal Zhukov's Unknown Battle, which made no attempt to cover up the huge losses suffered by Soviet forces. As a consequence, there were public calls in Russia for the arrest of some of those involved in its production.[33] In the movie, the casualties of Soviet forces are given as 433,000 KIA. The journalist Alina Makeyeva, in an article of Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper which was published on 19 February 2009, wrote: "The number presented by the historian is too low. There must be more than one million Soviet soldiers and officers killed! Rzhev and its neighboring towns were completely destroyed."; however, Makeyeva could not present any proof. Journalist Elena Tokaryeva in her article which was published in the newspaper The Violin (Russia) on 26 February 2009 also claimed that more than 1,000,000 Soviet soldiers were killed at Rzhev. The number of casualties again was raised with the claim of journalist Igor Elkov in his articled published in the Russian Weekly on 26 February 2009. Igor said: "The accurate number of casualties of both sides is still dubious. Recently, there are some opinions about from 1.3 to 1.5 million Soviet soldiers was killed. It may reach the number of 2 million".[34]

All this data was heavily criticized by historian A. V. Isayev. Referencing the data from the archives of the Russian Ministry of Defence, Isayev claimed that Igor Elkov's estimates were exaggerated, and claimed the casualties of the Soviet forces as below:[4]

- Casualties of Western Front on Rzhev direction, from January to April 1942: 24,339 KIA, 5,223 MIA, 105,021 WIA. (data of Ministry of Defence, code name TsAMO RF, shelf 208, drawer 2579, folder 6, volume 208, pp. 71–99).

- Casualties of Kalinin Front on Rzhev direction, from January to April 1942: 123,380 irrecoverable, 341,227 sanitary. (data of Ministry of Defence, code name TsAMO RF, shelf 208, drawer 2579, folder 16, volume ll, pp. 71–99).

- Total casualties of Western and Kalinin front during Jan-Apr 1942: 152,943 irrecoverable, 446,248 sanitary (above sources).

- Total casualties of 29th and 30th Army (Kalinin Front), 20th and 31st Army (Western Front) in August 1942: 57,968 irrecoverable and 165,999 sanitary. (data of Ministry of Defence, code name TsAMO RF, shelf 208, drawer 2579, folder 16, volume ll, pp. 150–158)

- Total casualties of 20th, 29th, 30th, 31st (Western Front) and 39th Army (Kalinin Front) in September 1942: 21,221 KIA and 54,378 WIA.(data of Ministry of Defence, code name TsAMO RF, shelf 208, drawer 2579, folder 16, volume ll, pp. 163–166).

- Total casualties of Kalinin Front during Operation Mars: 33,346 KIA, 3,620 MIA, 63,757 WIA. (above source).

- Total casualties of 20th, 30th, 31st Army and 2nd Guard Cavalry Corps from 21 to 30 November 1942 (first phase of Operation Mars): 7,893 KIA, 1,288 MIA, 28,989 WIA. (data of Ministry of Defence, code name TsAMO RF, shelf 208, drawer 2579, folder 16, volume ll, pp. 190–200).

Isayev also claimed that his estimates match the research of Colonel-General Grigoriy Krivosheyev, his superior at the Russian Military History Institute, which is considered[by whom?] the sole officially recognized source on Soviet casualties in WWII. Isayev also claims that the electronic draft of Krivosheyev's research was stolen and illegally used by the hackers, hence these drafts were completely deleted from the Institute Website.[35][36]

According to Isayev the total Soviet casualties at Rzhev from January 1942 to March 1943 were 392,554 KIA and 768,233 WIA. The documentary by Pivovarov was also disparaged by Isayev; who stated that in this film, many important events of the Rzhev battles are not mentioned such as the breakout of 1st Guard Cavalry Corps, the breakout of more than 17,000 remaining troops of 33rd Army during Operation Seydlitz, and the breakout of the 41st Army. According to Isayev, if the film of Pivovarov and the thesis of Gerasimova were true, many living people should have been recorded as KIA.

Role of Zhukov in Operation Mars

[edit]The role of Zhukov in this infamous offensive is also a debated topic. American military historian, Colonel David M. Glantz claimed that Zhukov had to take the main responsibility in the tactical failure of this operation, and this was "the greatest defeat of Marshal Zhukov." In more detail, David Glantz asserted that Zhukov's command in this offensive was not careful, too ambitious, too clumsy and all these led to a disaster.[37] However, Antony Beevor disagreed with Glantz's comment. According to Beevor, at that time Zhukov had to concentrate on Operation Uranus at Stalingrad, so he had little time to care about what was happening at Rzhev, which is questionable considering that Operation Uranus was planned by Andrei Yeremenko and Andrei Vasilevsky, and Zhukov played little to no part in it.[38]

The Russian authors Vladimir Chernov and Galina Green also disagreed with Glantz. They asserted that from 26 August 1942 Zhukov did not command the Western Front, and that from 29 August he was preoccupied with serious matters at Stalingrad.[39] It has been asserted[by whom?] that Stalin was actually the commander in charge of all the fronts at the Rzhev salient.[40] Zhukov took part in the command at Rzhev only during its later periods as a "firefighter" who was solving the serious problems of the battlefield at that moment.[41] Therefore, Beevor asserted that Glantz's comments about Zhukov's responsibility were incorrect.[38]

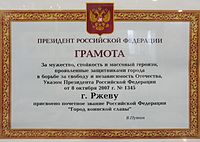

Memorials

[edit]City of Military Glory

[edit]Rzhev was conferred the status of "City of Military Glory" by the President of Russia Vladimir Putin on 8 October 2007, for "courage, endurance and mass heroism, exhibited by defenders of the city in the struggle for the freedom and independence of the Motherland".[42] This act also caused heated debate and controversy. Many people believed that Rzhev should not be a "City of Military Glory" since it was the Germans who were "defenders of the city" against numerous and unsuccessful Soviet attacks. However, according to the law, being occupied does not prevent a city from receiving this honorary title. As long as its citizens, military personnel and government officers paid a large contribution for the Great Patriotic War and expressed great heroism, bravery and patriotism in these contributions, that is enough. Furthermore, the fierce and heroic resistance of Soviet citizens at Rzhev not only occurred during the 1942–1943 period, but also during the defence of Moscow in 1941.[43][44][45] According to all these facts, Rzhev, Vyazma and many other cities have enough conditions to have the title "City of Military Glory," whether they were occupied or not.

Statue and memorial

[edit]The Rzhev Memorial to the Soviet Soldier was unveiled by the presidents of Russia and Belarus on 30 June 2020. The statue was designed by sculptor Andrei Korobtsov and architect Konstantin Fomin and is 25 metres high on a 10-metre mount, surrounded by a war memorial.[46][47]

References

[edit]- ^ Gerasimova 2016, p. 167-9.

- ^ Lopuhovskiy, L.N. (2008). 1941. Vyazemskaya disaster (PDF) (in Russian) (2nd, Revised ed.). Yauza Eksmo. ISBN 978-5-699-30305-2.

- ^ Isaev, Alexei V. (2005). Boilers 41st. The history of the Second World War, we did not know (in Russian). Yauza Eksmo. ISBN 5-699-12899-9.

- ^ a b c d Yamaletdinov, Ruslan. "Алексей Исаев. К ВОПРОСУ О ПОТЕРЯХ СОВЕТСКИХ ВОЙСК В БОЯХ ЗА РЖЕВСКИЙ ВЫСТУП. Актуальная история" [Alexey Isayev. On the Question of the Losses of the Soviet Troops in the Battle for the Rzhev Salient.]. actualhistory.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ Gerasimova 2016, p. 159.

- ^ "Military improvisations during the Russian Campaign". Archived from the original on 18 October 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ Tennant H. Bayley, Spy Wars: Moles, Mysteries and Deadly Games, 2007, Yale University Press, p. 117. Bayley cites Pavel Sudoplatov, Anatoly Sudoplatov, and Jerrold and Leona Schecter's book Special Tasks, published by Little, Brown in 1994, p. 158–159. He also quotes a KGB chief as writing, "Marshal Zhukov knew his offensive was an auxiliary operation, but he did not know that he had been targeted in advance by the Germans."

- ^ Гудериан Гейнц. Воспоминания солдата. — Смоленск.: Русич, 1999. (Guderian Heinz. Erinnerungen eines Soldaten. — Heidelberg, 1951. Rossiya Publisher. Smolensk. 1999. Chapter IX: Chief Inspector of Armoured Units) (in Russian)

- ^ Бевин Александер. 10 фатальных ошибок Гитлера. — М.:Яуза; Эксмо, 2003. (Alexander Bevin. How Hitler Could Have Won World War II: The Fatal Errors That Led to Nazi Defeat. L.:Times Books, 2000. Published at Moscow in 2003. Chapter 10: The Lost at Moscow; Chapter 19: "Citadel" collapsed) Archived 27 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Военная история ]-- Самсонов А.М. Крах фашистской агрессии 1939-1945". militera.lib.ru.

- ^ "РОССИЯ И СССР В ВОЙНАХ XX ВЕКА. Глава V. ВЕЛИКАЯ ОТЕЧЕСТВЕННАЯ ВОЙНА". rus-sky.com.

- ^ a b ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Исследования ]-- Бешанов В.В. Год 1942 - "учебный". militera.lib.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Военная история ]-- Исаев А. В. Когда внезапности уже не было". militera.lib.ru. Archived from the original on 8 August 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ Gerasimova 2016, p. 157.

- ^ Gerasimova 2016, p. 158.

- ^ Gerasimova 2016, pp. 158–159.

- ^ "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Военная история ]-- Гроссманн Х. Ржев - краеугольный камень Восточного фронта". militera.lib.ru.

- ^ "1942". Archived from the original on 28 December 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ "1943". Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ Gerasimova 2016, p. 166.

- ^ Man, Mole. "История Ржевской битвы 1941-1943 гг". rshew-42.narod.ru.

- ^ "Дулаг 184 - Лагерь военнопленных". dulag184.vyazma.info.

- ^ "Поиск родственников солдат, погибших во время ВОВ". stapravda.ru. 19 June 2009.

- ^ "Арон Шнеер. Плен. Глава 2. От теории к практике: эйнзацгруппы и их деятельность". jewniverse.ru.

- ^ Исаев, Алексей Валерьевич. Краткий курс истории ВОВ. Наступление маршала Шапошникова. — М.: Яуза, Эксмо, 2005.(Alexey Valeryevich Isayev. When the surprising element was lost. History of World War II - The Unknown Truth. Yauza & Penguin Books. Moskva. 2006. Part I: 1942 Summer-Autumn Offensive. Section 1: the first summer attacks) Archived 31 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ Кожевников, Михаил Николаевич. Командование и штаб ВВС Советской Армии в Великой Отечественной войне 1941-1945 гг. — М.: Наука, 1977. (Mikhail Nikolayevich Kozhevnikov. The Soviet Air Force Command and Staff in the Great Patriotic War (1941-1945). Science Publisher. Moskva. 1977. Chapter III, Section 2) (in Russian)

- ^ a b c G. K. Zhukov. Memoirs. Vol 2. Quân đội nhân dân Publisher. Hanoi. 1987. pp. 269–270. (in Vietnamese)

- ^ "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Мемуары ]-- Баграмян И.X. Так шли мы к победе". militera.lib.ru.

- ^ "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Военная история ]-- Кириченко П. И. Первым всегда трудно". militera.lib.ru. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Военная история ]-- Исаев А. Краткий курс истории ВОВ. Наступление маршала Шапошникова". militera.lib.ru.

- ^ "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Исследования ]-- Соколов Б.В. Неизвестный Жуков: портрет без ретуши в зеркале эпохи". militera.lib.ru.

- ^ "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Мемуары ]-- Белов П. А. За нами Москва". militera.lib.ru.

- ^ "Film Spurs Russia to Squelch Criticism of Soviet War Tactics - HistoryNet". historynet.com. 22 May 2009.

- ^ Man, Mole. "Ржевская битва 1941-1943 гг. Ржев - 1942". rshew-42.narod.ru.

- ^ "Наши новости". soldat.ru.

- ^ "РОССИЯ И СССР В ВОЙНАХ XX ВЕКА. ПОТЕРИ ВООРУЖЕННЫХ СИЛ". rus-sky.com.

- ^ Гланц, Дэвид М. Крупнейшее поражение Жукова. Катастрофа Красной Армии в операции «Марс» 1942 г. — М.: ACT: Астрель, 2006. Bản gốc: David M. Glantz Zhukov's Greatest Defeat: The Red Army's Epic Disaster in Operation Mars, 1942. — Lawrence (KS): University Press Of Kansas, 1999. (David M. Glantz. Thất bại lớn nhất của Zhukov - Thảm họa của Hồng quân trong Chiến dịch "Sao Hỏa" năm 1942 – Moskva: ACT: Astrel, 2006.)

- ^ a b Beevor, Antony (2012). The Second World War. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84497-6.

- ^ "К 70-летию Погорело-Городищенской и Ржевско-Сычёвской операций 1942 года". soldat.ru.

- ^ S. M. Stemenko. The Soviet General Staff in War. Moskva 1985. page 51.

- ^ "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА --[ Исследования ]-- Исаев А. В. Георгий Жуков". militera.lib.ru. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Президент Российской Федерации. Указ №1345 от 8 October 2007 года «О присвоении городу Ржеву почётного звания Российской Федерации "Город воинской славы"». (The President of the Russian Federation. Ukaz #1345 of October 8, 2007 On the assignment to Rzhev of the Honorary title of the Russian Federation "City of Military Glory". ).

- ^ "ФЕДЕРАЛЬНЫЙ ЗАКОН от 09.05.2006 N 68-ФЗ "О ПОЧЕТНОМ ЗВАНИИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ "ГОРОД ВОИНСКОЙ СЛАВЫ" (принят ГД ФС РФ 14.04.2006)". Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "О постановлении Правительства Российской Федерации от 13.07.2006 N 488, Телеграмма ФТС России от 23 августа 2006 года №ТФ-1938". docs.kodeks.ru.

- ^ "О внесении изменения в Положение об условиях и порядке присвоения почетного звания Российской Федерации "Город воинской славы", утвержденное Указом Президента Российской Федерации от 1 декабря 2006 года N 1340, Указ Президента РФ от 27 апреля 2007 года №557". docs.kodeks.ru.

- ^ "Unveiling of the Rzhev Memorial to the Soviet Soldier". 30 June 2020.

- ^ "Opening of Rzhev memorial described as landmark event for Belarusians". 30 June 2020.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Data used from Glantz 1998, pp. 295–296:

Rzhev–Vyazma strategic offensive operation: 1,059,200

First Rzhev–Sychyovka offensive operation: 345,100

Second Rzhev–Sychyovka offensive operation: 1,400,000

Rzhev–Vyazma offensive (1943): 876,000 - ^ March 1942 to March 1943 casualties of the 2nd, 4th, 9th, 2nd Panzer, 3rd Panzer and 4th Panzer Armies

Bibliography

[edit]- Buttar, Prit (2023). Meat Grinder: the Battles for the Rzhev Salient, 1942--43. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472851819.

- Gerasimova, Svetlana (2016). The Red Army's forgotten 15-month campaign against Army Group Center, 1942–1943. London: Helion and Company. ISBN 978-1-91109-614-6.

- Gorbachevsky, Boris (2008). Through the Maelstrom: A Red Army Soldier's War on the Eastern Front, 1942–1945. University Press of Kansas, ISBN 978-0-7006-1605-3, Hardcover, 443 pages, photos.

- Glantz, David (1998). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army stopped Hitler. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0899-0.

External links

[edit]- Rzhev Battle 1941–1943 (in Russian)

- Horst Grossmann Geschichte der rheinisch-westfaelischen 6 Infanterie-Division 1939–1945 (in German)

- German war photos (in Russian)

- Battles of Rzhev (in Russian)