Battle of the Spurs

| Battle of the Spurs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the League of Cambrai | |||||||

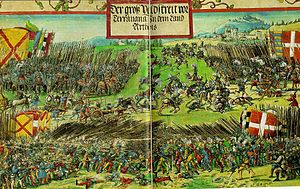

Triumphzug Kaiser Maximilians, Georg Lemberger | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

England Holy Roman Empire | France | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Henry VIII Maximilian I Henry Bourchier George Talbot Lord Herbert |

Jacques Palice (POW) Charles IV of Alençon Louis d'Orléans (POW) Chevalier de Bayard (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 30,000 overall, many fewer were engaged | 7,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light | 3,000 killed, wounded, captured, or missing | ||||||

Location within France | |||||||

The Battle of the Spurs or (Second) Battle of Guinegate[1] took place on 16 August 1513. It formed a part of the War of the League of Cambrai of 1508 to 1516, during the Italian Wars. King Henry VIII of England and Emperor Maximilian I were besieging the French town of Thérouanne in Artois (now Pas-de-Calais). Henry's camp was at Guinegate (present-day Enguinegatte).[2] A large body of French heavy cavalry under Jacques de La Palice was covering an attempt by light cavalry to bring supplies to the besieged garrison. English and Imperial troops surprised and routed the French cavalry. The battle resulted in the precipitate flight and extensive pursuit of the French. During the pursuit, a number of notable French leaders and knights were captured. After the fall of Thérouanne, Henry VIII besieged and took Tournai.

Prelude

[edit]Context

[edit]Henry VIII joined the Holy League, as the League of Cambrai was also known, on 13 October 1511 with Venice and Spain to defend the Papacy from its enemies and France with military force. Henry promised to attack France at Guyenne, landing 10,000 men at Hondarribia in the Basque Country in June 1512. This army was conveyed by the admiral Edward Howard, and commanded by Thomas Grey, 2nd Marquess of Dorset. It remained at Bayonne till October supporting Ferdinand II of Aragon's action in the Kingdom of Navarre, though undersupplied and in poor morale. Maximilian joined the league in November. Louis XII of France hoped that Scotland would aid France against England.[3]

Siege of Thérouanne

[edit]

In May 1513 English soldiers began to arrive in number at Calais to join an army commanded by George Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, Lord Steward of the Household. Shrewsbury was appointed Lieutenant-General on 12 May, John Hopton commanded the troop ships. On 17 May Henry announced to the Cinque Ports and Edward Poynings, Constable of Dover Castle, that he would join the invasion in person, and had appointed commissioners to requisition all shipping. In Henry's absence across the sea (ad partes transmarinas), Catherine of Aragon would rule England and Wales as Rector and Governor (Rectrix et Gubernatrix).[4]

The Chronicle of Calais recorded the names and arrivals of Henry's aristocratic military entourage from 6 June onwards. At the end of the month the army set out for Thérouanne. Shrewsbury commanded the vanguard of 8,000, and Charles Somerset, Lord Herbert the rearward of 6,000.[5] Henry VIII sailed from Dover,[6] and arrived at Calais on 30 June, with the main grouping of 11,000 men.[7] The army was provided by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey as Almoner, and comprised several different types of martial forces including cavalry, artillery, infantry, and longbowmen using arrows with hardened steel heads, designed to penetrate armour more effectively. Eight hundred German mercenaries marched in front of Henry.

Shrewsbury set up a battery and dug mines towards the town's walls, but made little progress against the defending garrison of French and German soldiers in July. The town was held for France by Antoine de Créquy, sieur de Pont-Remy who returned fire until the town surrendered, and the English called one distinctive regular cannon shot the "whistle."[8] Reports of setbacks and inefficiency reached Venice. On the way to Thérouanne two English cannon called "John the Evangelist" and the "Red Gun" had been abandoned, and French skirmishing hampered their recovery with loss of life. Edward Hall, the chronicle author, mentions the role of Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex in this operation and the advice given by Rhys ap Thomas.[9] An Imperial agent of Margaret of Savoy wrote that two "obstinate men" govern everything, these were Charles Brandon, Viscount Lisle who he called the "Grand Esquire" and the Almoner Wolsey.[10]

Henry camped to the east of Thérouanne at a heavily defended position, described by English chronicles as environed with artillery, such as "falcons, serpentines, cast hagbushes, tryde harowes, and spine trestles (bolt firing tarasnice)", with Henry's field accommodation consisting of a wooden cabin with an iron chimney, with large tents of blue water-work, yellow, and white fabric, topped by the King's beasts, the Lion, Dragon, Greyhound, Antelope, and Dun Cow.[11]

The Emperor Maximilian came to Aire-sur-la-Lys in August, with a small force (either a small escort that cannot be called an army[12] or about 1,000[13] to 4,000 horsemen,[14] depending on the sources). Henry donned light armour and dressed his entourage in cloth-of gold and came to Aire on 11 August, where Maximilian's followers were still dressed in black in mourning for his wife Bianca Maria Sforza. Henry hosted Maximilian at a tent with a gallery of cloth-of-gold at his camp over the weekend beginning 13 August. According to the chronicles, the weather on the day of the meeting was the "foulest ever."[15] News of Henry's meeting with Maximilian in person delighted Catherine of Aragon, who wrote to Wolsey that it was an honour for Henry and would raise Maximilian's reputation; he would be "taken for a nother man that he was befor thought".[16]

Louis XII of France determined to break the siege. In July a force of 800 Albanians commanded by Captain Fonterailles pushed through the besieger's lines and successfully delivered gunpowder and supplies including bacon to the gates of the town, leaving 80 soldiers as reinforcements. Fonterailles was helped by covering artillery fire from the town. Reports sent to Venice mentioned 300 English casualties or more, and Fonterailles' statement that the town could hold out till the feast day of the Nativity of the Virgin, on 8 September. The Venetians were aware that their French sources might have been misrepresenting the situation to gain their support.[17]

Battle

[edit]French attempt to supply Thérouanne

[edit]

A second French attempt was organized for 16 August, with a force assembled at Blangy to the south. This French army was made up of companies of gendarmes and pikemen, with some other troops as well. These included a type of French light cavalry called "stradiotes" (stradiots), equipped with short stirrups, beaver hats, light lances, and Turkish swords. These may have been Albanian units.[18]

In response to the new threat, English military engineers had built five bridges overnight over the river Lys to allow their army free passage to the other side and Henry moved his camp to Guinegate (now called Enguinegatte), on 14 August, after displacing a company of French horse armed with spears who were stationed at the Tower of Guinegate.[19]

The French infantry were left at Blangy, while the heavy cavalry were divided into two companies, one under the command of La Palice and Louis, Duke of Longueville, the other under Charles IV, Duke of Alençon. Alençon's smaller force attacked the besieging positions commanded by Lord Shrewsbury, the larger force against the south of the besieging lines where Lord Herbert commanded.[20] Both attacks were designed to act as diversions in order that the stradiots be able to reach Thérouanne with supplies. Each stradiot had a side of bacon at his saddlebow and a sack of gunpowder behind him.[21]

Combat

[edit]

The French had hoped to catch the besieging army unprepared by moving out before dawn; however, the English 'border prickers' (light cavalry from the Scottish borders) were out and they detected the movement of the larger of the two bodies of French cavalry. Henry VIII drew up a field force from the siege lines sending out a vanguard of 1,100 cavalry, following this with 10,000–12,000 infantry. La Palice's force encountered English scouts at the village of Bomy, 5 miles from Thérouanne; the French, realising that the English were alert, checked themselves on the edge of a hillside. The stradiots then began their rather forlorn attempt to contact the garrison, riding in a wide arc towards the town.[20]

Historical accounts derived from English and Imperial sources differ slightly.

According to Sir Charles Oman, whose narrative is largely based on the mid-16th century English Chronicle of Edward Hall, La Palice made a mistake in staying in his exposed position too long, presumably he was doing so in order to allow the stradiots the greatest possibility of success. The English heavy cavalry of the vanguard drew up opposite Palice's front, while the mounted archers dismounted and shot at the French from a flanking hedgerow. Now aware of the approach of the English infantry in overwhelming numbers, La Palice tardily ordered his force to retreat. At this point the Clarenceux Herald is said to have urged the Earl of Essex to charge. The English men-at-arms and other heavy cavalry charged just as the French were moving off, throwing them into disorder. To complete the French disarray, the stradiots crashed in confusion into the flank of the French heavy cavalry, having been driven off from approaching the town by cannon fire. At much the same time, a body of Imperial cavalry also arrived to menace the other flank of the French horsemen. Panic now seized the French cavalry, whose retreat became a rout. La Palice tried to rally them but to no effect. In order to flee more quickly the French gendarmes threw away their lances and standards, some even cut away the heavy armour of their horses. The chase went on for many miles until the French reached their infantry at Blangy. During the pursuit many notable French knights were captured, along with a royal duke and the French commander, La Palice, himself.[22][23] Meanwhile, the smaller French force had been driven off, Sir Rhys ap Thomas capturing four of their standards.[24] The initial cavalry clash took place between the village of Bomy and Henry's camp at Guinegate.[25]

According to Reinhold Pauli and others, Maximilian recommended that parts of the troops should be sent to the flank and rear of the enemy and lighter cannons should be put on the ridge of the neighbouring hill. He then commanded 2,000 vanguard cavalry troops himself.[26][27][28] Marchal reports that the emperor had prepared the battle plan in mind even before arriving at the English headquarters.[29] Henry had wanted to lead the cavalry charge but was advised against this by his allies; so the task fell upon the 53-year-old emperor (he had won two battles in the same area, including the First Guinegate where he was a young leader supported by veterans), who in battle acted as commander-in-chief of the allied forces and directed the military operations in person. He charged with the cavalry against the French as soon as contact was made. [30][31] The French cavalry initially charged back strongly, but quickly gave way and retreated. According to Howitt, the French retreat was intended as a distraction that would allow Duke of Alençon to provide the city with supplies (but the Duke was repelled by Lord Herbert before reaching the gates of the city), but soon turned into a disastrous flight that the French commanders could not control.[14]

Contemporary accounts

[edit]The day was soon called the "Battle of the Spurs" (in French: La Journée d'Esperons) because of the haste of the French horse to leave the battlefield. In the summer of 1518 the English ambassador in Spain, Lord Berners, joked that the French had learned to ride fast at the "jurney of Spurres."[32]

The same evening the Imperial Master of the Posts, Baptiste de Tassis sent news of the battle to Margaret of Savoy from Aire-sur-la-Lys in Artois;

Early in the day the Emperor and the King of England encountered 8,000 French horse; the Emperor, with 2,000 only, kept them at bay until four in the afternoon, when they were put to flight. A hundred men of arms were left upon the field, and more than a hundred taken prisoners, of the best men in France; as the Sieur de Piennes, the Marquis de Rotelin, and others.[33]

Henry sent his account to Margaret of Savoy on the following day. He mentioned that the French cavalry had first attacked Shrewsbury's position blockading the town, capturing 44 men and wounding 22. An Imperial cavalry manoeuvre brought the French horse within range of the guns, and the French cavalry fled.[34]

The chronicle writer Edward Hall gave a somewhat different account. Hall, who says the French called it the "battle of the Spurs", centres the action around a hill, with English archers at the village of "Bomye." He has the French cavalry break after a show of English banners organized by the Clarenceux Herald, Thomas Benolt. Hall mentions that Maximilian advised Henry to deploy some artillery on another hill "for out-scourers" but does not mention any effect on the outcome. Although Henry wished to ride into the battle, he stayed with the Emperor's foot soldiers on the advice of his council.[35]

After a three-mile chase, amongst the French prisoners were Jacques de la Palice, Pierre Terrail, seigneur de Bayard and Louis d'Orléans, Duke of Longueville. Although reports mention the Emperor's decision for his troops to serve under Henry's standard,[36] Hall's account suggests friction between the English and Imperial forces, during the day and over prisoners taken by the Empire, who were "not brought to sight" and released. Henry returned to his camp at Enguinegatte and heard reports of the day's actions. During the fighting the garrison of Thérouanne had come out and attacked Herbert's position.[37] According to the report, three English soldiers of note were killed, with 3,000 French casualties. Nine French standards were captured, with 21 noble prisoners dressed in cloth-of-gold.[38]

Aftermath

[edit]Fall of Thérouanne

[edit]On 20 August, now unthreatened by French counter-attacks, Henry moved his camp from Guinegate to the south of the town. Thérouanne fell on 22 August, according to diplomatic reports the garrison were initially unimpressed by a show of captured colours, but the French and German garrison were drawn into negotiation with Shrewsbury by their lack of supplies. Shrewsbury welcomed Henry to the town and gave him the keys. Eight or nine hundred soldiers were set to work demolishing the walls of the town and three large bastions which were pushed into the deep defensive ditches. The dry ditches contained deeper pits which were designed for fires to create smoke to choke assailants. The Milanese ambassador to Maximilian, Paolo Da Laude, heard that it was planned to burn the town after demolition was completed.[39] On 5 September Pope Leo X was told of the English victories by the Florentine ambassador and his congratulations were conveyed to Cardinal Wolsey.[40]

Siege of Tournai

[edit]

While demolition continued at Thérouanne, after discussions on 4 September, allied attention moved to Tournai, though Henry would have preferred an attack on Boulogne. Maximilian and Henry went to St Pol, St Venan, Neve and Béthune, and on 10 September Henry entered Lille with great ceremony where Margaret of Savoy held court. That evening, Henry played on the lute, harp, lyre, flute, and horn,[42] and danced with "Madame the Bastard" till nearly dawn, "like a stag", according to the Milanese ambassador. The same day the army began the siege of Tournai, and Maximilian and Henry visited on 13 September.[43]

At this time Henry VIII was troubled by Scottish preparations for the invasion of England in support of France and had exchanged angry words with a Scottish herald at Thérouanne on 11 August.[44] The Scots army was defeated at the battle of Flodden on 9 September. Before Tournai fell Catherine of Aragon sent John Glyn to Henry with the blood-stained coat and gauntlets of James IV of Scotland. Catherine suggested Henry should use the coat as his battle-banner, and wrote that she had thought to send him the body too, but "Englishmen's hearts would not suffer it." It was suggested that James' body would be her exchange with Henry for his French prisoner, the Duke of Longueville. Longueville had been captured at Thérouanne by John Clerke of North Weston, sent to Catherine, and lodged in the Tower of London. The idea of an exchange was reported to Alfonso d'Este Duke of Ferrara in Italy, that Catherine had promised, as Henry "sent her a captive duke, she should soon send him a king".[45]

Tournai fell to Henry VIII on 23 September. The defenders of Tournai had demolished houses in front of their gates on 11 September, and burnt their suburbs on 13 September. On 15 September the wives and children of the townspeople were ordered to repair damage to the walls caused by the besieger's cannon. On the same day the town council proposed a vote on whether the town should declare for France or the Empire. The vote was suspended (mis en surseance) and the people appointed deputies to treat with Henry VIII. Charles Brandon captured one of the gatehouses and took away two of its statues as trophies, and the garrison negotiated with Henry and Richard Foxe, Bishop of Winchester, on 20 September.[46] The events within the town were misunderstood in English chronicles, Raphael Holinshed and Richard Grafton wrote that a disaffected "vaunt-parler" had set fire to the suburbs to hasten their surrender, while the Provost canvassed the townspeople's opinion.[47]

Henry attended mass in Tournai Cathedral on 2 October and knighted many of his captains. The town presented Margaret of Austria with a set of tapestries woven with scenes from the Book of the City of Ladies by Christine de Pizan.[48] Tournai remained in English hands, with William Blount, 4th Baron Mountjoy as Governor. The fortifications and a new citadel were reconstructed between August 1515 and January 1518, costing around £40,000. Work ceased because Henry VIII planned to restore the town to France. Tournai was returned by treaty on 4 October 1518. The surveyor of Berwick, Thomas Pawne, could not find a market for the unused building materials there, and sent stones by boat via Antwerp to Calais, some carved with English insignia, along with the machinery of two watermills. The construction work at Tournai has been characterized as retrogressive, lacking the input of a professional military engineer, and an "essentially medieval" conception out of step with Italian innovations.[49]

Propaganda

[edit]

Henry and Maximilian jointly published an account of their victories, under the title; Copia von der erlichen und kostlichen enpfahung ouch früntliche erbietung desz Küngs von Engelland Keyser Maximilian in Bickardy (Picardy) gethon, Unnd von dem angryff und nyderlegung do selbs vor Terbona (Thérouanne) geschähen. Ouch was un wy vyl volck do gewäsen, erschlagen, und gefangen. Ouch die Belägerung der stat Bornay (sic: Tournai) und ander seltzam geschichten, (1513), which can be translated as; Of the honourable and sumptuous reception and friendly courtesy shown by the King of England to the Emperor Maximilian in Picardy; and of the attack and defeat which took place there before Thérouanne. Also what and how many people there were slain and captured. Also the siege of the town of Tournay and other strange histories.The book contains a woodcut of their meeting and one of Maximilian in battle. The battle at Guinegate was described in this manner;

About twelve o'clock the French in three divisions appeared upon another hill (for here and there are little hills and valleys); and as soon as the Emperor knew it he got up and sent for the German horsemen, numbering scarcely 1,050, and the Burgundians, about 1,000 (or 2,000), and commanded to muster the troops and to keep the Germans by him. The French united in one division amounting to 10,000 (or 7,000) cavalry in array and fired guns at the Emperor's horsemen, but all went too high and did no hurt. Thus the Burgundians and certain English struck [them], and as they turned and the Emperor saw the Burgundians hard pressed, he at once ordered the German horsemen to attack on the flank; but before they struck the French had turned about and fled. Our horsemen pursued them until within a short mile of their camp and brought back the prisoners and banners hereafter indicated. When the Emperor saw that no more harm could be done them, and they were near their camp wherein were yet 20,000 foot, he retired all the men in good order and marched to the camp, remaining all night in the field. In this skirmish the English used no other cry than Burgundia.[50]

An Italian poem, La Rotta de Francciosi a Terroana on the fall of Therouanne was printed in Rome in September 1513.[51] Maximilian also commissioned woodcut images of his meeting with Henry from Leonhard Beck, and from Albrecht Dürer who included a scene of the mounted rulers joining hands in the Triumphal Arch.[52] Henry commissioned commemorative paintings of the meeting and of the battle which showed him involved in the centre of the action, though Hall pointed out he took advice to stay with the foot soldiers.[53] In Henry's inventory, one painting was noted as "A Table wherein is conteined the Seginge of Torney and Turwyn".[54] A painting made by "Master Hans", perhaps Hans Holbein in 1527 for a banqueting house at Greenwich Palace showed the siege of Therouanne with the "very manner of every man's camp". Henry VIII insisted that his guests, the French ambassadors, should turn to look at the picture.[55]

Maximilian's tomb at the Hofkirche, Innsbruck, constructed in 1553 to designs by Florian Abel includes a marble relief of the meeting by Alexander Colyn following Dürer's woodcut. In the immediate aftermath of the battle, Maximilian objected to the use of his name in the battle report (even before that, he adopted the red rose and the Cross of Saint George, and declared that he would serve as Henry's soldier, to avoid the complaint that his force was too small in comparison with his position and his promises).[56][57][58] According to Patrick Fraser Tytler, Howitt and others, Maximilian had an ulterior motive in his flattering behaviours towards Henry, which was later understood by some historians (such as Comyn[59]) as Maximilian acting like a mercenary soldier, as Henry was the side who footed the bill for the whole campaign. Additionally, Maximilian wanted to destroy the city walls of Tournai (which usually served as a foothold for French intervention and threatened his grandson Charles's Burgundian territories). He accomplished this with his counsel and the help of Thomas Wolsey, to whom he promised help in getting the bishopric of Tournai (Wolsey, who turned out to be the biggest winner in the aftermath according to Derek Wilson, did get the bishoprics of both Lincoln and Tournai. Later he relinquished the latter in exchange for a pension of 12,000 livres.).[60][61][62][63] On the other hand, Henry VIII and his queen Catherine did feel genuine gratitude for Maximilian's assistance and later sent him the sizeable sum of 100,000 golden florin.[64]

English knights made at the Battle of Spurs and in Tournai

[edit]The following were made knights banneret after the battle of the Spurs on 16 September 1513,[65] Edward Hall specifically mentioned the knighting of John Peachy, captain of the King's horse, as a banneret and John Car who was "sore hurt" as a knight.[66]

- Andrew Wyndsore, Treasurer of the King's middle-ward

- Robert Dymoke, Treasurer of the rear-ward

- Randolph Brereton, marshall of the rear-ward

- John Arundell

- John Aston

- Thomas Cornwall

- Piers Edgecombe

- Henry Guildford

- John Hussey of Sleaford

- John Seymour

- Anthony Ughtred

- Thomas West

- Henry Wyatt

- John Audely

- Thomas Blount

- Richard Carew

- Henry Clifford

- George Holford

- Thomas Leighton

- William Pierpoint

- John Reynsford

- Henry Sacheverell

- John Warbleton

- Richard Wentworth

On 2 October 1513, after Henry attended mass at Tournai Cathedral the following were knighted:[67]

- John Tuchet, Lord Audely

- Thomas Brooke, Lord Cobham

- Edward, Lord Grey

- Anthony Wingfield

- Thomas Tyrell of Gipping

- Christopher Willoughby of Parham

- Edward Guildford

- William Compton

- Richard Sacheverell

- Thomas Tyrell of Heron, Essex

- William Eure

- Thomas Borough

- Robert Tyrwhit

- Thomas Fairfax

- Edward Hungerford and Walter Hungerford

- Giles Capell

- Edward Doon

- Edward Belknape

- Edward Ferrers

- William Hussey

- Owen Perrot

- William Fitzwilliam

- Christopher Garneys

- Henry Poole

- John Vere

- John Marney

- John Markham

- John Savage

- Edward Stradling

- John Ragland

- Edward Chamberlain

- William Griffiths

- William Parr

- Edward Neville

- John Neville of Liversedge, captain of Northern Light Horsemen

- Robert Neville of Liversedge, (knighted at Lille)

- William Essex

- Ralph Egerton

- James Framlingham

- John Mainwaring

- John Mainwaring of Ightfield, (knighted at Lille)

- William Tyler

- John Sharpe

- Thomas Lovell, junior of Barton Bendish

- Richard Jerningham

- Lewis Orell

- Geffrey Gates

- Richard Tempest

- William Brereton

- Henry Owen

- John Giffard

- Henry Longe

- William Hansarde

- William Ascu (Askew) or Ainscough of Stallingborough

- Christopher Ascu (Askew)

- John Zowkett (German)

- Lewis de Waldencourt ("de Hannonia")

- Nicholas Barrington

- John Bruges

- William Finch

- George Harvey

- Nicholas Heydon

- Lionel Dymoke

- Edward Benstead

- William Smith

- John Daunce

- Thomas Clinton

- Richard Whethill

- William Thomas

- John Wiseman

- The heir of Baron Zouche

- (Edward) Sutton, heir of Baron Dudley

- Christopher Baynham of Clearwell

With others, and more including Walter Calverley (1483–1536) were knighted at Lille on 13 and 14 October.[68]

Notes

[edit]- ^ (French: Journée des éperons, "Day of the Spurs"; deuxième bataille de Guinegatte)

- ^ English contemporary sources call the town "Turwyn".

- ^ Mackie 1952, pp. 271–277; Brewer 1920, nos. 1176, 1239, 1286, 1292, 1326–27, 1375, 1422

- ^ Rymer 1712, pp. 367–370.

- ^ Mackie 1952, pp. 277–279

- ^ HMC Calendar of Manuscripts of the Marquess of Salisbury, vol. 1 (London, 1883), pp. 3–4.

- ^ Nichols 1846, pp. 10–13.

- ^ Potter 2003, p. 137; Hall, Edward, and Richard Grafton, Chronicle (1809), pp. 259–264, has "Bresquy" for Créquy

- ^ Hall 1809, p. 542; Grafton, Richard, Chronicle at Large, vol. 1 (1809), pp. 256, 257–258

- ^ Brewer 1920, no. 2051 & following papers, see no. 2071 & 2141

- ^ Hall 1809, p. 543; Grafton, Richard, Chronicle at Large, vol. 1 (1809), pp. 259, 260; Henry's tents at Thérouanne are also depicted in paintings (see external links) and detailed in a British Library manuscript, BL Add MS 11321 fol. 97–100

- ^ MacFarlane, Charles (1851). The cabinet history of England, an abridgment of the chapters entitled 'Civil and military history' in the Pictorial history of England [by G.L. Craik and C. MacFarlane] with a continuation to the present time. 13 vols. [in 26]. Blackie and son. pp. 87, 88. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Law, Ernest (1916). England's First Great War Minister: How Wolsey Made a New Army and Navy and Organized the English Expedition to Artois and Flanders in 1513, and how Things which Happened Then May Inspire and Guide Us Now in 1916. G. Bell & Sons. p. 230. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ a b Howitt 1865, pp. 127, 128.

- ^ Hall 1809, pp. 544–545, 548–489; Brewer 1920, no. 2227

- ^ Ellis 1825, p. 85.

- ^ Brown 1867, nos. 269, 271, 273–274, 281, 291 (possibly exaggerated reports heard in Venice)

- ^ Hall 1809, pp. 543, 550.

- ^ Grafton 1809, p. 262.

- ^ a b Oman 1998, p. 293.

- ^ Oman 1998, pp. 292–293.

- ^ Oman 1998, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Hall, p. 550

- ^ Oman 1998, p. 295.

- ^ Brewer 1920, no. 2227, newsletter locating the battle at Bomy; Lingard 1860, pp. 15–17; Brown 1867, no. 308 (Sanuto diaries)

- ^ Pauli, Reinhard (2012). Beiträge zur Englischen Geschichte bis 1880. Dogma. p. 194. ISBN 9783955072056. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Guggenberger, Anthony (1913). A General History of the Christian Era: The Protestant revolution. 10th and 11th ed. 1918. B. Herder. p. 105. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ Howitt, William (1865). John Cassell's illustrated history of England. The text, to the reign of Edward i by J.F. Smith; and from that period by W. Howitt, Volume 2. Cassell, ltd. pp. 127, 128. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Marchal (chevalier), François Joseph Ferdinand (1836). Histoire politique du règne de l'empereur Charles Quint. H. Tarlier. p. 191. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ MacFarlane 1851, p. 89.

- ^ Menzel, Thomas (2003). Der Fürst als Feldherr: militärisches Handeln und Selbstdarstellung zwischen 1470 und 1550 : dargestellt an ausgewählten Beispielen. Logos. p. 123. ISBN 9783832502409. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ J. G. Nichols, ed., Diary of Henry Machyn, Camden Society (1848), p. 401; Letters & Papers, vol. 2 (1864), no. 4282

- ^ Brewer 1920, no. 2168, translated from French

- ^ Brewer 1920, no. 2170

- ^ Hall, p. 550

- ^ Brewer 1920, no. 2227

- ^ Hall 1809, pp. 550–551.

- ^ Brewer 1920, no. 2227

- ^ Brown 1867, no. 308 (Sanuto diaries); Brewer 1920, no. 2227

- ^ Rymer, Thomas, ed., Foedera, vol. 13 (1712), p. 376

- ^ Colvin, Howard, ed., History of the King's Works, vol. 3 part 1, HMSO (1975), pp. 375–382

- ^ Brown 1867, no. 328; instruments identified in Dumitrescu, Theodor, Early Modern Court and International Musical Relations, Ashgate, (2007), p. 37, citing Helms, Dietrich, Heinrich VIII. und die Musik, Eisenach, (1998)

- ^ Hinds 1912, pp. 390–397, "Madame" was a lady-in-waiting of Margaret, who is called here the "Madame of Spain."

- ^ Brewer 1920, p. 972 no. 2157

- ^ Ellis 1825, pp. 82–84, 88–89; Ellis 1846, pp. 152–154; Brown 1867, no. 328; Brewer 1920, no. 2268

- ^ Brewer 1920, nos. 2286–87, 2294 (extracts from the records of Tournai.); Brown 1867, no. 316

- ^ Grafton, Richard, Chronicle at Large, vol. 2 (1809), p. 267; Holinshed, Chronicle, vol 3 (1808), p. 588, a "vaunt-parler" was a spokesman, an official position in contemporary Tournai (e.g., L&P, vol. 3, no. 493), but the term suggested busy-body in English.

- ^ Bell, Susan Groag, The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies, University of California, (2004), pp. 42–44, 72–73

- ^ Colvin, Howard, ed., History of the King's Works, vol. 3 part 1, HMSO (1975), pp. 375–382; Cruikshank 1971, pp. 169–175; Pepper, Simon, The chivalric ethos and the development of Military Professionalism, (2003), p. 136; Hocquet, A., 'Tournai et l'occupation Anglaise,' in Annales de la Société Historique et Archéoloqie de Tournai, no. 5 (1900), p. 325

- ^ Brewer 1920, no. 2173 & extract translated in appendix

- ^ Brewer 1920, no. 2247, noted: reprinted La Rotta de Francciosi a Terroana novamente facta, La Rotta do Scocesi, Roxburghe Club, no. 37, (1825), presented by Earl Spencer.

- ^ See "Historical subjects from the Triumphal Arch," British Museum collection database; Schauerte, Thomas Ulrich, Die Ehrenpforte für Kaiser Maximilian I, Deutscher Kunstverlag, (2001), pp. 281–282, the complete woodcut has the following Latin inscription; "Illud vero laude non caret, cu' Flandos, atque sicambros suos valida manu inviseret, ut reges Angliae partes, ad versus regem Franciae tueretur, Id quod sine sanguine fieri nequit, Unde cu' iam utraque ex parte dimicatum esset fortiter, ac utinque haud pauci occubissent victoriu portitas est Caesar deinde Terrauonam solo aequevet Tornavia, oppugnationem nom sustilem pacta pace cu' Caesare, in potestatem illum receptem."

- ^ Painting of the battle, Royal Collection, Bridgman Art Library

- ^ Starkey 1998, p. 385 no. 15413; Lloyd & Turley 1990, p. 48; Bentley-Cranch 2004, pp. 62–63

- ^ Sydney Anglo, Spectacle Pageantry, and Early Tudor Policy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), pp. 215, 220.

- ^ Nye, Bill (1900). Bill Nye's History of England: From the Druids to the Reign of Henry VIII. Lippincott. p. 1513. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Smith, John Frederick, ed. (1858). John Cassell's Illustrated History of England, Volume 2. W. Kent and Company. pp. 124–126. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Bowle, John (1965). Henry VIII: A Biography. Allen & Unwin. p. 59. ISBN 978-7250008888. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Comyn (Sir), Robert Buckley (1841). The History of the Western Empire. Vol. 2. W.H. Allen & Company. p. 41. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Tytler, Patrick Fraser (1854). Life of Henry the Eighth: With Biographical Sketches Of...contemporaries... Nelson. p. 56. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Howitt 1865, p. 129.

- ^ Smith 1858, pp. 124–126.

- ^ Wilson, Derek (2013). A Brief History of Henry VIII: King, Reformer and Tyrant. Hachette UK. p. 47. ISBN 978-1472107633. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Barany, George (1986). The Anglo-Russian Entente Cordiale of 1697–1698: Peter I and William III at Utrecht. East European Monographs. p. 80. ISBN 978-0880331043.

- ^ Shaw 1906, p. 31.

- ^ Hall 1809, p. 551.

- ^ Metcalfe 1885, pp. 45–56; however according to Hall 1809, pp. 565–566, the manuscript quoted in Metcalfe (1885) has an impossible date of "25 December 1513" and instead Hall dates it to 2 October 1513

- ^ Shaw 1906, p. 42.

References

[edit]- Bentley-Cranch, Dana (2004), The Renaissance Portrait in France and England, Honore Champion, pp. 62–63

- Brewer, J.S., ed. (1920), Letters & Papers Henry VIII, vol. 1, Institute of Historical Research

- Brown, Rawdon, ed. (1867), Calendar of State Papers Relating to English Affairs in the Archives of Venice (1509–1519), vol. 2, Institute of Historical Research

- Cruikshank, Charles Greig (1971), The English Occupation of Tournai, Clarendon Press

- Ellis, Henry, ed. (1825), Original Letters Illustrative of English History, First Series, vol. 1 (Second ed.), London: Harding, Triphook, & Lepard

- Ellis, Henry, ed. (1846), Original Letters Illustrative of English History, 3rd Series, vol. 1, pp. 152–154

- Grafton, Richard (1809), Chronicle at Large, vol. 2, p. 262

- Hinds, Allen B., ed. (1912), Calendar State Papers, Milan, vol. 1, Institute of Historical Research

- Hall, Edward (1809), Chronicle: Union of the Two Noble and Illustrate Families of Lancastre and Yorke (collated eds. of 1548 and 1550), London: J. Johnson, F.C. Rivington, etc., p. 550

- Lingard, John (1860), History of England, vol. 6, New York: O'Shea

- Lloyd, Christopher; Turley, Simon (1990), Henry VIII, Images of a Tudor King, Phaidon / HRP, p. 48

- Mackie, J.D. (1952), Earlier Tudors, 1485–1558, Oxford

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nichols, John Gough, ed. (1846), Richard Turpyn's Chronicle of Calais, Camden Society, pp. 10–15, 67–68

- Metcalfe, Walter Charles (1885), A Book of Knights Banneret, Knights of the Bath, and Knights Bachelor made between the fourth year of King Henry VI and the restoration of King Charles II ..., London: Mitchell and Hughes

- Oman, Sir Charles W. C. (1998), History of the Art of War in the 16th Century (reprinted ed.), Greenhill Books, ISBN 0-947898-69-7

- Potter, David (2003), War and Government in the French Provinces, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521893008

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rymer, Thomas, ed. (1712), Foedera, Conventiones, Literae, Et Cujuscunque Generis Acta Publica, Inter Reges Angliae, vol. 13 (Latin & English)

- Shaw, William Arthur (1906), The Knights of England: A complete record from the earliest time to the present day of the knights of all the orders of chivalry in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and of knights bachelors, incorporating a complete list of knights bachelors dubbed in Ireland, vol. 2, London: Sherratt and Hughes

- Starkey, David, ed. (1998), Inventory of Henry VIII, p. 385

External links

[edit]- Painting of 'The Meeting of Henry VIII and the Emperor Maximilian I', RCT RCIN 405800

- Painting of the Battle of Spurs, RCT RCIN 406784

- English painting of the meeting at Thérouanne , c. 1520 at the Tower of London, via UK National Education Network

- Albrecht Dürer's woodcut of the meeting, Auckland Art Gallery, (without inscription)

- History of fortification at Tournai, Fortified Places Archived 9 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- 1513 in France

- Battles of the War of the League of Cambrai

- Battles involving England

- Battles involving France

- Battles involving the Holy Roman Empire

- Military history of Hauts-de-France

- Conflicts in 1513

- 16th-century military history of the Kingdom of England

- England–France relations

- Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

- Henry VIII