Battle of Diamond Hill

| Battle of Diamond Hill | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Second Boer War | |||||||

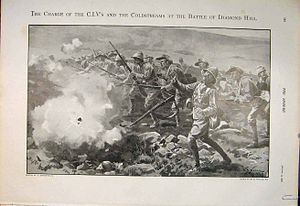

The Charge of the City of London Imperial Volunteers ('CIVs') and Coldstreams at the Battle of Diamond Hill, after a drawing by William Barnes Wollen | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000 men and 83 guns[1] | Up to 6,000 men and 30 guns[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 28 killed and 145 wounded[1] |

About 30 killed and wounded Several captured[1] | ||||||

The Battle of Diamond Hill (Donkerhoek) (Afrikaans: Slag van Donkerhoek) was an engagement of the Second Boer War that took place on 11 and 12 June 1900 in central Transvaal.

Background

[edit]The Boer forces retreated to the east by the time the capital of the South African Republic (Transvaal), Pretoria, was captured by British forces on 5 June 1900. British Commander-in-Chief in South Africa Field Marshal Lord Roberts had predicted a Boer surrender upon the loss of their capital, but when this was not fulfilled, he began an attack to the east in order to push Boer forces away from Pretoria and enable an advance to the Portuguese East Africa border.[1]

Prelude

[edit]The commandant-general of Transvaal, Louis Botha, established a 40-kilometer north to south defensive line 29 kilometers east of Pretoria; his forces numbered up to 6,000 men and 30 guns. The Pretoria–Delagoa Bay rail line ran eastward through the center of the Boer position. Personnel from the South African Republic Police manned positions at Donkerpoort just south of the railway in the hills at Pienaarspoort, while other troops held positions at Donkerhoek and Diamond Hill. Botha commanded the Boer centre and left flank and General Koos de la Rey commanded north of the railway line.[1]

Weakened by the long march to Pretoria and the loss of horses and sick men, the British force mustered only 14,000, a third of whom were mounted on wobbly horses.[2]

He despatched Robert Broadwood's 2nd Cavalry Brigade, which included the 10th Royal Hussars, 12th Royal Lancers and the Household Cavalry Regiment, on a Special Mission.

As the sun came up it was a "bitterly cold Monday morning...we are hidden in the hills at Donkerhoek...ready for battle..." confided Botha to his diary.[3]

Battle

[edit]The cavalry of John French with Edward Hutton's brigade attacked on the left in an attempt to outflank the Boers to the north, while the infantry of Ian Hamilton with Lieutenant Colonel Beauvoir De Lisle's corps attempted an outflanking movement on the right. In the center, the infantry of Reginald Pole-Carew advanced towards the Boer center, with the gap between Pole-Carew and French covered by Colonel St.G.C. Henry's corps of mounted infantry.[2]

On the left, the cavalry of French entered a valley and attracted fire from three sides. De Lisle's corps was similarly pinned down on the right flank in a horseshoe-shaped group of hills. As a detachment of 10th Hussars swung off to the right, they were attacked from Diamond Hill. A section of Q Battery RHA attempted to return artillery fire, but had no infantry support, until the 12th Lancers arrived on the front line. Lord Airlie took 60 men to clear the Boers from the guns, and in the ensuing exchange of rifle fire at short-range, Lord Airlie was killed. The Boers pressed the matter hard. Two squadrons of the Household Cavalry Regiment and one squadron of the 12th Hussars charged at full gallop at Boers firing from concealed positions. The enemy dispersed.[4] Following the indecisive results of 11 June, Roberts decided to make a frontal attack on the next morning.[2]

The morning of 12 June with artillery fire from guns escorted to forward positions by a squadron of New South Wales Mounted Rifles led by Captain Maurice Hilliard, allowing a Regular infantry advance that captured Diamond Hill. A counterattack was planned by Botha, supported with fire from Rhenosterfontein Hill. The regular Mounted Infantry from De Lisle's corps advanced to a farm, where two rapid firing pom-poms were positioned, supported by the Western Australian Mounted Infantry of Hatherley Moor. The hill was attacked by the New South Wales Mounted Rifles, who trotted across the plain in extended order, then increased to a gallop under Boer fire before they dismounted at the base of the hill. The mounted rifles advanced up the hill and charged the Boer defenders, forcing the latter to retreat. They held the hill despite Boer artillery fire, which forced Botha to call off the counterattack, as British artillery fire from the hill carried the potential to confusion with the Boer retreat.[clarification needed] Among those killed in the attack were Lieutenants Percy Drage and William Harriott of the New South Wales Mounted Rifles.[2]

On the morning of 13 June De Lisle's corps pursued the retreating Boers until they expended their ammunition and received artillery fire in return.[2]

Aftermath

[edit]On 13th the Botha's army retreated to the north, they were chased as far as Elands River Station, only 25 miles from Pretoria, by Mounted Infantry and De Lisle's Australians.[5][6][7][8] Although Roberts had removed the Boer threat to his eastern flank, the Boers were unbowed despite their retreat. Jan Smuts wrote that the battle had "an inspiriting effect which could scarcely have been improved by a real victory."[9]

Forty-four years after the battle, British General Ian Hamilton opined in his memoirs that "the battle, which ensured that the Boers could not recapture Pretoria, was the turning point of the war". Hamilton credited war correspondent Winston Churchill with recognizing that the key to victory would be in storming the summit, and risking his life to signal Hamilton.[10]

Order of battle

[edit]British Forces

[edit]| South African Field Force | Field Marshal Lord Roberts |

| Cavalry Division (Lieutenant General John French) | |

| 1st Cavalry Brigade: Colonel T.C. Porter | 4th Cavalry Brigade: Major General J.B.B. Dickson |

| 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys) | 7th Dragoon Guards |

| 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons | 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars |

| Carabiniers (6th Dragoon Guards) | 14th King's Hussars |

| New South Wales Lancers | O Battery, Royal Horse Artillery |

| 1st Australian Horse | E Section Pom-Poms |

| T Battery, Royal Horse Artillery | |

| J Section Pom-Poms | |

| 1st Mounted Infantry Brigade (Major-General Edward Hutton) | |

| 1st Corps Mounted Infantry: Lt-Col. Edwin Alderson | 3rd Corps Mounted Infantry: Lt-Col. Thomas Pilcher |

| 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles | Queensland Mounted Infantry |

| 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles | New Zealand Mounted Infantry |

| 1st Battalion Mounted Infantry | 3rd Battalion Mounted Infantry |

| G Battery Royal Horse Artillery | |

| C Section Pom-Poms | |

| 4th Corps Mounted Infantry: Colonel St.G.C. Henry | |

| South Australian Mounted Rifles | 4th Battalion Mounted Infantry |

| Tasmanian Mounted Infantry | J Battery, Royal Horse Artillery |

| Victorian Mounted Rifles | L Section Pom-Poms |

| 7th Imperial Yeomanry[11] | |

| 11th Division (Lieutenant General Reginald Pole-Carew) | |

| 1st (Guards') Brigade: Major-General Inigo Jones | 18th Brigade: Major General Theodore Stephenson |

| 3rd Grenadier Guards | 1st Essex |

| 1st Coldstream Guards | 1st Yorkshire |

| 2nd Coldstream Guards | 2nd Royal Warwickshire |

| 1st Scots Guards | 1st Welsh |

| Division troops | |

| 2nd West Australian Mounted Infantry | Struben's Scouts |

| Prince Alfred's Guard (detachment) | 12th Imperial Yeomanry |

| 83rd Field Battery, Royal Artillery | 2 x Naval 4.7-inch guns (Bearcroft's) |

| 84th Field Battery, Royal Artillery | 2 x Naval 12-pounders |

| 85th Field Battery, Royal Artillery | 2 x 5-inch siege guns (Foster's) |

| Column of Lieutenant General Ian Hamilton | |

| 2nd Cavalry Brigade: Major General Robert George Broadwood | 3rd Cavalry Brigade: Brigadier General J.R.P. Gordon |

| Composite Regiment of Household Cavalry | 9th Lancers |

| 10th Hussars | 16th Lancers |

| 12th Lancers | 17th Lancers |

| Q Battery, Royal Horse Artillery | R Battery, Royal Horse Artillery |

| K Section Pom-Poms | D Section Pom-Poms |

| 21st Brigade: Major General Bruce Hamilton | |

| 1st Royal Sussex | 1st Derbyshire |

| 1st Cameron Highlanders | City Imperial Volunteers[12][13] |

| 76th Field Battery, Royal Artillery | 82nd Field Battery, Royal Artillery |

| 2 x 5-inch siege guns (Massie's)[14] | |

| 2nd Mounted Infantry Brigade: Brigadier General Charles Parker Ridley | |

| 2nd Corps Mounted Infantry: Lieutenant Colonel Beauvoir De Lisle | 5th Corps Mounted Infantry: Lieutenant Colonel H.L. Dawson |

| West Australian Mounted Infantry | Marshall's Horse |

| 6th Battalion Mounted Infantry | Roberts' Horse |

| New South Wales Mounted Rifles | Ceylon Mounted Infantry |

| P Battery, Royal Horse Artillery | 5th Battalion Mounted Infantry |

| A Section Pom-Poms | |

| 6th Corps Mounted Infantry: Lieutenant Colonel Norton Legge | 7th Corps Mounted Infantry: Lieutenant Colonel Guy Bainbridge |

| Kitchener's Horse | Burma Mounted Infantry |

| City Imperial Volunteers Mounted Infantry | Rimington's Guides |

| 2nd Battalion Mounted Infantry | 7th Battalion Mounted Infantry |

| Derby Mounted Infantry (2 companies)[12][13] | |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Wessels 2017, pp. 236–237.

- ^ a b c d e Wilcox 2002, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Battle of Diamond Hill

- ^ Viljoen, My Reminiscences

- ^ "Diamond Hill – Rundle's Operations". Historion.net.

- ^ "Letter From The Front". The Inverell Times. Vol. 21, no. 2849. New South Wales. 18 August 1900. p. 2. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "The Diamond Hill Fight". The Age. No. 14, 133. Victoria, Australia. 22 June 1900. p. 5. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ "The Battle of Diamond Hill". Windsor and Richmond Gazette. Vol. 12, no. 641. New South Wales. 26 January 1901. p. 1. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ Pakenham 1992, p. 160.

- ^ Kelly (2008) pp. 57–58

- ^ Maurice 1908, p. 217.

- ^ a b Williams 1906, pp. 503–505.

- ^ a b Williams 1906, p. 280.

- ^ Williams 1906, p. 290.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brian Kelly, Best Little Stories from the Life and Times of Winston Churchill, Cumberland House Publishing, 2008

- Sir George Arthur, The Story of the Household Cavalry 1887–1900, vol.III

- Maurice, John Frederick, ed. (1908). History of the war in South Africa, 1899–1902. Vol. III. London: Hurst and Blackett. – Official history

- Pakenham, Thomas (1992). The Boer War (Paperback ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 9780380720019.

- Williams, Basil, ed. (1906). The Times History of the War in South Africa, 1899-1902. Vol. IV. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ben Viljoen, My Reminiscences of the Anglo-Boer War, (Hood, Douglas and Howard 1902)

- Wessels, André (2017). "Diamond Hill (Donkerhoek), Battle of (June 11–12, 1900)". In Stapleton, Timothy J. (ed.). Encyclopedia of African Colonial Conflicts. Vol. I. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598848373.

- Wilcox, Craig (2002). Australia's Boer War: The War in South Africa 1899–1902. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-551637-0.