Odia language

| Odia | |

|---|---|

| Oṛiā | |

| ଓଡ଼ିଆ | |

The word "Oṛiā" in Odia script | |

| Pronunciation | [oˈɽia] (Odia) /əˈdiːə/ (English)[1] |

| Native to | India |

| Region | Eastern India

|

| Ethnicity | Odias, Scheduled Tribes of Odisha |

Native speakers | L1: 38 million (2011–2019)[5][6] L2: 3.6 million[5] |

Early forms | Prakrit

|

Standard forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Odisha Sahitya Akademi, Government of Odisha[10] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | or |

| ISO 639-2 | ori |

| ISO 639-3 | ori – inclusive codeIndividual codes: ory – Odiaspv – Sambalpuriort – Adivasi Odia (Kotia)dso – Desia (South-western) (duplicate of [ort])[11] |

| Glottolog | macr1269 Macro-Oriya (Odra)oriy1255 Odia |

Odia majority or plurality

Significant Odia minority | |

Odia (/əˈdiːə/;[1][12] ଓଡ଼ିଆ, ISO: Oṛiā, pronounced [oˈɽia] ;[13] formerly rendered as Oriya) is a classical Indo-Aryan language spoken in the Indian state of Odisha. It is the official language in Odisha (formerly rendered as Orissa),[14] where native speakers make up 82% of the population,[15] and it is also spoken in parts of West Bengal,[16] Jharkhand, Andhra Pradesh and Chhattisgarh.[17] Odia is one of the many official languages of India; it is the official language of Odisha and the second official language of Jharkhand. The Odia language has various dialects varieties, including the Baleswari Odia (Northern dialect), Kataki (central dialect), Ganjami Odia (Southern dialect), Sundargadi Odia (Northwestern dialect), Sambalpuri (Western dialect), Desia (South-western dialect) and Tribal Community dialects who spoken by the tribals groups in Odisha who adopted the Odia language.[2][3][4]

Odia is the sixth Indian language to be designated a classical language, on the basis of having a long literary history and not having borrowed extensively from other languages.[18][19][20][21] The earliest known inscription in Odia dates back to the 10th century CE.[22]

History

[edit]Odia is an Eastern Indo-Aryan language belonging to the Indo-Aryan language family. It descends from Odra Prakrit which itself evolved from Magadhi Prakrit.[23] The latter was spoken in east India over 1,500 years ago, and is the primary language used in early Jain and Buddhist texts.[24] Odia appears to have had relatively little influence from Persian and Arabic, compared to other major Indo-Aryan languages.[25]

The history of the Odia language is divided into eras:

- Proto-Odia (Odra Prakrit) (10th century and earlier): Inscriptions from 9th century shows the evolution of proto-Odia, i.e. Odra Prakrit or Oriya Prakrit words used along with Sanskrit. The inscriptions are dated to third quarter of 9th century during the reign of early Eastern Gangas.[27]

- Old Odia (10th century till 13th century): Inscriptions from the 10th century onwards provide evidence for the existence of the Old Odia language, with the earliest inscription being the Urajam inscription of the Eastern Gangas written in Old Odia in 1051 CE.[26] Old Odia written in the form of connected lines is found in inscription dated to 1249 CE.[28]

- Early Middle Odia (13th century–15th century): The earliest use of prose can be found in the Madala Panji of the Jagannath Temple at Puri, which dates back to the 12th century. Such works as Sisu Beda, Amarakosa, Gorekha Samhita, Kalasa Chautisa and Saptanga are written in this form of Odia.[29][30][31]

- Middle Odia (15th century–17th century): Sarala Das writes the Mahabharata and Bilanka Ramayana.[32][33] Towards the 15th century, Panchasakha 'five seer poets' namely Balarama Dasa, Jagannatha Dasa, Achyutananda Dasa, Sisu Ananta Dasa and Jasobanta Dasa wrote a number of popular works, including the Odia Bhagabata, Jagamohana Ramayana, Lakshmi Purana, Haribansa, Gobinda Chandra and more. Balarama Dasa, Ananta Dasa and Achyutananda Dasa of Pancha Sakha group hailed from Karana community.[34]

- Late Middle Odia (17th century–Early 19th century): Usabhilasa of Sisu Sankara Dasa, the Rahasya Manjari of Deba Durlabha Dasa and the Rukmini Bibaha of Kartika Dasa were written. Upendra Bhanja took a leading role in this period with his creations Baidehisa Bilasa, Koti Brahmanda Sundari, Labanyabati which emerged as landmarks in Odia Literature. Dinakrushna Dasa's Rasakallola and Abhimanyu Samanta Singhara's Bidagdha Chintamani were prominent latter kabyas. Of the song poets who spearheaded Odissi music, classical music of the state – Upendra Bhanja, Banamali, Kabisurjya Baladeba Ratha, Gopalakrusna were prominent. Bhima Bhoi emerged towards the end of the 19th century.

- Modern Odia (Late 19th century to present): The first Odia magazine, Bodha Dayini was published in Balasore in 1861. During this time many Bengali scholars claimed that Odia was just a dialect of Bengali to exercise of power by cornering government jobs.[35] For instance Pandit Kanti Chandra Bhattacharya, a teacher of Balasore Zilla School, published a little pamphlet named 'Odia Ekti Swatantray Bhasha Noi' (Odia not an independent language) where Bhattacharya claimed that Odia was not a separate and original form of language and was a mere corruption of Bengali. He suggested British Government to abolish all Odia Vernacular Schools from Odisha and to alter into Bengali Vernacular Schools.[36] The first Odia newspaper Utkala Deepika, launched in 1866 under editors Gourishankar Ray and Bichitrananda. In 1869 Bhagavati Charan Das started another newspaper, Utkal Subhakari. More Odia newspapers soon followed like Utkal Patra, Utkal Hiteisini from Cuttack, Utkal Darpan and Sambada Vahika from Balasore and Sambalpur Hiteisini from Deogarh. Fakir Mohan Senapati emerged as a prominent Odia fiction writer of this time and Radhanath Ray as a prominent Odia poet. Other prominent Odia writers who helped promote Odia at this time were Madhusudan Das, Madhusudan Rao, Gangadhar Meher, Chintamani Mohanty, Nanda Kishore Bal, Reba Ray, Gopabandhu Das and Nilakantha Das.

Poet Jayadeva's literary contribution

[edit]Jayadeva was a Sanskrit poet. He was born in an Utkala Brahmin family of Puri [citation needed] around 1200 CE. He is most known for his composition, the epic poem Gita Govinda, which depicts the divine love of the Hindu deity Krishna and his consort, Radha, and is considered an important text in the Bhakti movement of Hinduism. About the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th, the influence of Jayadeva's literary contribution changed the pattern of versification in Odia.[citation needed]

Geographical distribution

[edit]India

[edit]Distribution of Odia language in the state of India[37]

According to the 2011 census, there are 37.52 million Odia speakers in India, making up 3.1% of the country's population. Among these, 93% reside in Odisha.[38][39] Odia is also spoken in neighbouring states such as Chhattisgarh (913,581), Jharkhand (531,077), Andhra Pradesh (361,471), and West Bengal (162,142).[37]

Due to worker migration as tea garden workers in colonial India, northeastern states Assam and Tripura have a sizeable Odia-speaking population,[37] particularly in Sonitpur, Tinsukia, Udalguri, Sivasagar, Golaghat, Dibrugarh, Cachar, Nagaon, Karimganj, Karbi Anglong, Jorhat, Lakhimpur, Baksa, Kamrup Metropolitan, Hailakandi district of Assam and West Tripura, Dhalai, North Tripura district of Tripura. Similarly, due to increasing worker migration in modern India, the western states Gujarat and Maharashtra also have a significant Odia speaking population.[40] Additionally, due to economic pursuits, significant numbers of Odia speakers can be found in Indian cities such as Vishakhapatnam, Hyderabad, Pondicherry, Bangalore, Chennai, Goa, Mumbai, Raipur, Jamshedpur, Vadodara, Ahmedabad, New Delhi, Guwahati, Shillong, Pune, Gurgaon, Jammu and Silvassa.[41]

Foreign countries

[edit]The Odia diaspora is sizeable in several countries around the world, bringing the number of Odia speakers worldwide to 50 million.[42][43][page needed][need quotation to verify] It has a significant presence in eastern countries, such as Thailand and Indonesia, mainly brought by the sadhaba, ancient traders from Odisha who carried the language along with the culture during the old-day trading,[44] and in western countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia and England. The language has also spread to Burma, Malaysia, Fiji, Mauritius, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Middle East countries.[43]

Standardisation and dialects

[edit]Major varieties or dialects

[edit]- Baleswari (Northern Odia): Spoken in Baleswar, Bhadrak, Mayurbhanj and Kendujhar districts of Odisha and southern parts of undivided Midnapore of West Bengal. The variant spoken in Baleswar is called Baleswaria.

- Kataki (Central Odia):[45] Spoken in the coastal and central regions consisting of Cuttack, Khordha, Puri, Nayagarh, Jajpur, Jagatsinghpur, Kendrapara, Dhenkanal, Angul, Debagarh and parts of Boudh districts of Odisha with regional variations. The Cuttack variant is known as Katakia.

- Ganjami (Southern Odia): Spoken in Ganjam, Gajapati and parts of Kandhamal districts of Odisha, Srikakulam district of Andhra Pradesh. The variant spoken in Berhampur is also known as Berhampuria.

- Sundargadi (Northwestern Odia): Spoken in Sundergarh and parts of adjoining districts of Odisha and the districts of Jashpur of Chhattisgarh and Simdega of Jharkhand.[47][48]

- Sambalpuri (Western Odia): It is the western dialect/variety of Odia language with the core variant spoken in Sambalpur, Jharsuguda, Bargarh, Balangir and Subarnapur districts, along with parts of Nuapada and western parts of Boudh districts of Odisha. Also spoken in parts of Raigarh, Mahasamund and Raipur districts of Chhattisgarh. A 2006 survey of the varieties spoken in four villages in Western Odisha found out that Sambalpuri share three-quarters of their basic vocabulary with Standard Odia and has 75%–76% lexical similarity with Standard Odia.[49][50][51]

- Desia (Southwestern Odia/Koraputi): Spoken in southwestern districts of Nabarangpur, Rayagada, Koraput, Malkangiri and southern parts of Kalahandi districts of Odisha and in the hilly regions of Vishakhapatnam and, Vizianagaram districts of Andhra Pradesh.[51] A variant spoken in Koraput is also known as Koraputia.

Minor regional dialects

- Medinipuri Odia (Medinipuria): Spoken in parts of undivided Midnapore district and Kakdwip subdivision (South 24 Parganas) of West Bengal.[52]

- Singhbhumi Odia: Spoken in parts of East Singhbhum, West Singhbhum and Saraikela-Kharsawan district of Jharkhand.

- Phulbani Odia: spoken in Kandhamal and in parts of Boudh district.

- Kalahandia Odia: Variant of Odia spoken in Kalahandi and Nuapada districts and neighbouring districts of Chhattisgarh.

- Debagadia Odia: Variant of Odia spoken in Debagarh district and the adjoining Rairakhol, Athmallik area. It is known as Debgadia or Deogarhia.

Major tribal and community dialects/sociolects

[edit]- Bodo Parja (Jharia): spoken by the Parang Proja tribe of Koraput and neighbouring districts of Odisha.

- Bhatri: language variety spoken by the Bhottada tribe in Odisha and Chhattisgarh.[53][54]

- Reli: language variety spoken by the Reli people in the Koraput and Rayagada districts of southern Odisha and bordering districts of Andhra Pradesh.

- Kupia: language variety spoken by Valmiki people of Odisha and Andhra Pradesh, mostly in Koraput, and Visakhapatnam districts.

Minor sociolects

Odia minor dialects include:[55]

- Bhuyan: Tribal dialect spoken in Northern Odisha.

- Kurmi: Northern Odisha and Southwest Bengal.

- Sounti: Spoken in Northern Odisha and Southwest Bengal.

- Bathudi: Spoken in Northern Odisha and Southwest Bengal.

- Kondhan: Tribal dialect spoken in Western Odisha.

- Agharia: Spoken by Agharia community in districts of Western Odisha and Chhattisgarh.

- Bhulia: Spoken by Bhulia community in districts of Western Odisha and Chhattisgarh.

- Matia: Tribal dialect spoken in Southern Odisha.

Phonology

[edit]Odia has 30 consonant phonemes, 2 semivowel phonemes and 6 vowel phonemes.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Low | a | ɔ |

Length is not contrastive. The vowel [ɛ] can also be heard as an allophone of /e/, or as an allophone of the coalescence of the sequences /j + a/ or /j + ɔ/.[58] Final vowels are pronounced in the standard language, e.g. Odia [pʰulɔ] contrasts Bengali [pʰul] "flower".[59]

| Labial | Alveolar /Dental |

Retroflex | Post alv./ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɳ | ŋ | |||

| Stop/ Affricate |

voiceless | p | t | ʈ | tʃ | k | |

| voiceless aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | ||

| voiced | b | d | ɖ | dʒ | ɡ | ||

| voiced aspirated | bʱ | dʱ | ɖʱ | dʒʱ | ɡʱ | ||

| Fricative | s | ɦ | |||||

| Trill/Flap | r~ɾ | (ɽ, ɽʰ) | |||||

| Lateral | l | ɭ | |||||

| Approximant | w | j | |||||

Odia retains the voiced retroflex lateral approximant [ɭ],[56] among the Eastern Indo-Aryan languages. The velar nasal [ŋ] is given phonemic status in some analyses, as it also occurs as a terminal sound, e.g. ଏବଂ- ebaṅ /ebɔŋ/[61] Nasals assimilate for place in nasal–stop clusters. /ɖ ɖʱ/ have the near-allophonic intervocalic[62] flaps [ɽ ɽʱ] in intervocalic position and in final position (but not at morpheme boundaries). Stops are sometimes deaspirated between /s/ and a vowel or an open syllable /s/+vowel and a vowel. Some speakers distinguish between single and geminate consonants.[63]

Grammar

[edit]Odia retains most of the cases of Sanskrit, though the nominative and vocative have merged (both without a separate marker), as have the accusative and dative. There are three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter) and two grammatical numbers(singular and plural). However, there are no grammatical genders. The usage of gender is semantic, i.e. to differentiate male members of a class from female members.[64] There are three tenses coded via affixes (i.e., present, past and future), others being expressed via auxiliaries.

Writing system

[edit]

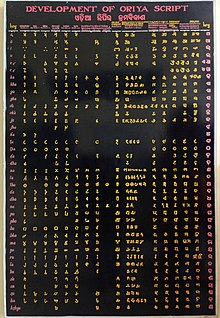

The Odia language uses the Odia script (also known as the Kalinga script). It is a Brahmic script used to write primarily the Odia language and others like Sanskrit and several minor regional languages. The script has developed over nearly 1000 years, with the earliest trace of the script being dated to 1051 AD.

Odia is a syllabic alphabet, or an abugida, wherein all consonants have an inherent vowel. Diacritics (which can appear above, below, before, or after the consonant they belong to) are used to change the form of the inherent vowel. When vowels appear at the beginning of a syllable, they are written as independent letters. Also, when certain consonants occur together, special conjunct symbols are used to combine the essential parts of each consonant symbol.

The curved appearance of the Odia script is a result of the practice of writing on palm leaves, which have a tendency to tear if too many straight lines are used.[65]

Odia script

[edit]| ଅ | ଆ | ଇ | ଈ | ଉ | ଊ | ଋ | ୠ | ଌ | ୡ | ଏ | ଐ | ଓ | ଔ |

| କ | ଖ | ଗ | ଘ | ଙ |

| ଚ | ଛ | ଜ | ଝ | ଞ |

| ଟ | ଠ | ଡ | ଢ | ଣ |

| ତ | ଥ | ଦ | ଧ | ନ |

| ପ | ଫ | ବ | ଭ | ମ |

| ଯ | ର | ଳ | ୱ | |

| ଶ | ଷ | ସ | ହ | |

| ୟ | ଲ | ଡ଼ | ଢ଼ | କ୍ଷ |

| ା | ି | ୀ | ୁ | ୂ | ୃ | ୄ | ୢ | ୣ | େ | ୈ | ୋ | ୌ |

| ଂ | ଃ | ଁ | ୍ | ଼ | । | ॥ | ଽ | ଓଁ | ୰ |

| ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ |

Literature

[edit]The earliest literature in Odia can be traced to the Charyapadas, composed in the 7th to 9th centuries.[66] Before Sarala Das, the most important works in Odia literature are the Shishu Veda, Saptanga, Amara Kosha, Rudrasudhanidhi, Kesaba Koili, Kalasa Chautisa, etc.[29][30][31] In the 14th century, the poet Sarala Das wrote the Sarala Mahabharata, Chandi Purana, and Vilanka Ramayana, in praise of the goddess Durga. Rama-Bibaha, written by Arjuna Dasa, was the first long poem written in the Odia language.

The following era is termed the Panchasakha Age and stretches until the year 1700. Notable religious works of the Panchasakha Age include those of Balarama Dasa, Jagannatha Dasa, Yasovanta, Ananta and Acyutananda. The authors of this period mainly translated, adapted, or imitated Sanskrit literature. Other prominent works of the period include the Usabhilasa of Sisu Sankara Dasa, the Rahasya Manjari of Debadurlabha Dasa and the Rukmini Bibha of Kartika Dasa. A new form of novels in verse evolved during the beginning of the 17th century when Ramachandra Pattanayaka wrote Harabali. Other poets, like Madhusudana, Bhima Dhibara, Sadasiba and Sisu Iswara Dasa composed another form called kavyas (long poems) based on themes from Puranas, with an emphasis on plain, simple language.

However, during the Bhanja Age (also known as the Age of Riti Yuga) beginning with turn of the 18th century, verbally tricky Odia became the order of the day. Verbal jugglery and eroticism characterise the period between 1700 and 1850, particularly in the works of the era's eponymous poet Upendra Bhanja (1670–1720). Bhanja's work inspired many imitators, of which the most notable is Arakshita Das. Family chronicles in prose relating religious festivals and rituals are also characteristic of the period.

The first Odia printing typeset was cast in 1836 by Christian missionaries. Although the handwritten Odia script of the time closely resembled the Bengali and Assamese scripts, the one adopted for the printed typesets was significantly different, leaning more towards the Tamil script and Telugu script. Amos Sutton produced an Oriya Bible (1840), Oriya Dictionary (1841–43) and[67] An Introductory Grammar of Oriya (1844).[68]

Odia has a rich literary heritage dating back to the thirteenth century. Sarala Dasa who lived in the fourteenth century is known as the Vyasa of Odisha. He wrote the Mahabharata into Odia. In fact, the language was initially standardised through a process of translating or transcreating classical Sanskrit texts such as the Mahabharata, Ramayana and the Bhagavad Gita. The translation of the Bhagavatam by Atibadi Jagannatha Dasa was particularly influential on the written form of the language. Another of the Panchasakha, Matta Balarama Dasa transcreated the Ramayana in Odia, titled Jagamohana Ramayana. Odia has had a strong tradition of poetry, especially devotional poetry.

Other eminent Odia poets include Kabi Samrat Upendra Bhanja, Kabisurjya Baladeba Ratha, Banamali Dasa, Dinakrusna Dasa and Gopalakrusna Pattanayaka. Classical Odia literature is inextricably tied to music, and most of it was written for singing, set to traditional Odissi ragas and talas. These compositions form the core of the system of Odissi music, the classical music of the state.

Three great poets and prose writers, Kabibar Radhanath Ray (1849–1908), Fakir Mohan Senapati (1843–1918) and Madhusudan Rao (1853–1912) made Odia their own. They brought in a modern outlook and spirit into Odia literature. Around the same time the modern drama took birth in the works of Rama Sankara Ray beginning with Kanci-Kaveri (1880).

Among the contemporaries of Fakir Mohan, four novelists deserve special mention: Aparna Panda, Mrutyunjay Rath, Ram Chandra Acharya and Brajabandhu Mishra. Aparna Panda's Kalavati and Brajabandhu Mishra's Basanta Malati were both published in 1902, the year in which Chha Mana Atha Guntha came out in the book form. Brajabandhu Mishra's Basanta Malati, which came out from Bamanda, depicts the conflict between a poor but highly educated young man and a wealthy and highly egoistic young woman whose conjugal life is seriously affected by ego clashes. Through a story of union, separation and reunion, the novelist delineates the psychological state of a young woman in separation from her husband and examines the significance of marriage as a social institution in traditional Indian society. Ram Chandra Acharya wrote about seven novels during 1924–1936. All his novels are historical romances based on the historical events in Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Odisha. Mrutyunjay Rath's novel, Adbhuta Parinama, published in 1915, centres round a young Hindu who gets converted to Christianity to marry a Christian girl.

One of the great writers in the 20th century was Pandit Krushna Chandra Kar (1907–1995) from Cuttack, who wrote many books for children like Pari Raija, Kuhuka Raija, Panchatantra, Adi Jugara Galpa Mala, etc. He was last felicitated by the Sahitya Academy in 1971–72 for his contributions to Odia literature, development of children's fiction, and biographies.

One of the prominent writers of the 20th and 21st centuries was Muralidhar Mallick (1927–2002). His contribution to Historical novels is beyond words. He was last felicitated by the Sahitya Academy in the year 1998 for his contributions to Odia literature. His son Khagendranath Mallick (born 1951) is also a writer. His contribution towards poetry, criticism, essays, story and novels is commendable. He was the former President of Utkal Kala Parishad and also former President of Odisha Geeti Kabi Samaj. Presently he is a member of the Executive Committee of Utkal Sahitya Samaj. Another illustrious writer of the 20th century was Chintamani Das. A noted academician, he was written more than 40 books including fiction, short stories, biographies and storybooks for children. Born in 1903 in Sriramachandrapur village under Satyabadi block, Chintamani Das is the only writer who has written biographies on all the five 'Pancha Sakhas' of Satyabadi namely Pandit Gopabandhu Das, Acharya Harihara, Nilakantha Das, Krupasindhu Mishra and Pandit Godabarisha. Having served as the Head of the Odia department of Khallikote College, Berhampur, Chintamani Das was felicitated with the Sahitya Akademi Samman in 1970 for his outstanding contribution to Odia literature in general and Satyabadi Yuga literature in particular. Some of his well-known literary creations are 'Bhala Manisha Hua', 'Manishi Nilakantha', 'Kabi Godabarisha', 'Byasakabi Fakiramohan', 'Usha', 'Barabati'.

20th century writers in Odia include Pallikabi Nanda Kishore Bal, Gangadhar Meher, Chintamani Mahanti and Kuntala Kumari Sabat, besides Niladri Dasa and Gopabandhu Das. The most notable novelists were Umesa Sarakara, Divyasimha Panigrahi, Gopala Chandra Praharaj and Kalindi Charan Panigrahi. Sachi Kanta Rauta Ray is the great introducer of the ultra-modern style in modern Odia poetry. Others who took up this form were Godabarisha Mohapatra, Mayadhar Mansingh, Nityananda Mahapatra and Kunjabihari Dasa. Prabhasa Chandra Satpathi is known for his translations of some western classics apart from Udayanatha Shadangi, Sunanda Kara and Surendranatha Dwivedi. Criticism, essays and history also became major lines of writing in the Odia language. Esteemed writers in this field were Professor Girija Shankar Ray, Pandit Vinayaka Misra, Professor Gauri Kumara Brahma, Jagabandhu Simha and Harekrushna Mahatab. Odia literature mirrors the industrious, peaceful and artistic image of the Odia people who have offered and gifted much to the Indian civilisation in the field of art and literature. Now Writers Manoj Das's creations motivated and inspired people towards a positive lifestyle. Distinguished prose writers of the modern period include Baidyanath Misra, Fakir Mohan Senapati, Madhusudan Das, Godabarisha Mohapatra, Kalindi Charan Panigrahi, Surendra Mohanty, Manoj Das, Kishori Charan Das, Gopinath Mohanty, Rabi Patnaik, Chandrasekhar Rath, Binapani Mohanty, Bhikari Rath, Jagadish Mohanty, Sarojini Sahoo, Yashodhara Mishra, Ramchandra Behera, Padmaja Pal. But it is poetry that makes modern Odia literature a force to reckon with. Poets like Kabibar Radhanath Ray, Sachidananda Routray, Guruprasad Mohanty, Soubhagya Misra, Ramakanta Rath, Sitakanta Mohapatra, Rajendra Kishore Panda, Pratibha Satpathy have made significant contributions towards Indian poetry.

Anita Desai's novella, Translator Translated, from her collection The Art of Disappearance, features a translator of a fictive Odia short story writer. The novella contains a discussion of the perils of translating works composed in regional Indian languages into English.

Four writers in Odia – Gopinath Mohanty, Sachidananda Routray, Sitakant Mahapatra and Pratibha Ray – have been awarded the Jnanpith, an Indian literary award.

Sample text

[edit]The following is a sample text in Odia of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (ମାନବିକ ଅଧିକାରର ସାର୍ବଜନୀନ ଘୋଷଣା):

Odia in the Odia script

- ଅନୁଚ୍ଛେଦ ୧: ସମସ୍ତ ମନୁଷ୍ୟ ଜନ୍ମକାଳରୁ ସ୍ୱାଧୀନ ଏବଂ ମର୍ଯ୍ୟାଦା ଓ ଅଧିକାରରେ ସମାନ । ସେମାନଙ୍କଠାରେ ବୁଦ୍ଧି ଓ ବିବେକ ନିହିତ ଅଛି ଏବଂ ସେମାନଙ୍କୁ ପରସ୍ପର ପ୍ରତି ଭ୍ରାତୃତ୍ୱ ମନୋଭାବରେ ବ୍ୟବହାର କରିବା ଉଚିତ୍ ।

Odia in IAST

- Anuccheda eka: Samasta manuṣya janmakāḷaru swādhīna ebaṅ marẏyādā o adhikārare samāna. Semānaṅkaṭhāre buuddhi o bibeka nihita achi ebaṅ semānaṅku paraspara prati bhrātr̥twa manobhābare byabahāra karibā ucit.

Odia in the IPA

- ɔnut͡ːʃʰed̪ɔ ekɔ: sɔmɔst̪ɔ mɔnuʂjɔ d͡ʒɔnmɔkaɭɔɾu swad̪ʱinɔ ebɔŋ mɔɾd͡ʒjad̪a o ɔd̪ʱikaɾɔɾe sɔmanɔ. semanɔŋkɔʈʰaɾe bud̪ːʱi o bibekɔ niɦit̪ɔ ɔt͡ʃʰi ebɔŋ semanɔŋku pɔɾɔspɔɾɔ pɾɔt̪i bʱɾat̪ɾut̪wɔ mɔnobʱabɔɾe bjɔbɔɦaɾɔ kɔɾiba ut͡ʃit̪

Gloss

- Article 1: All human beings from birth are free and dignity and rights are equal. Their reason and intelligence endowed with and they towards one another in a brotherhood spirit behaviour to do should.

Translation

- Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Software

[edit]Google introduced the first automated translator for Odia in 2020.[69] Microsoft too incorporated Odia in its automated translator later that year.[70]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Odia", Lexico.

- ^ a b c "Oriya gets its due in neighbouring state- Orissa". IBNLive. 4 September 2011. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b c Naresh Chandra Pattanayak (1 September 2011). "Oriya second language in Jharkhand". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012.

- ^ a b c "Bengali, Oriya among 12 dialects as 2nd language in Jharkhand". daily.bhaskar.com. 31 August 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- ^ a b Odia language at Ethnologue (22nd ed., 2019)

- ^ "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength – 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

- ^ "Jharkhand gives second language status to Magahi, Angika, Bhojpuri and Maithili". The Avenue Mail. 21 March 2018. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ "West Bengal Official Language Act, 1961". bareactslive.com. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Roy, Anirban (28 February 2018). "Kamtapuri, Rajbanshi make it to list of official languages in". India Today. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ "Odisha Sahitya Academy". Department of Culture, Government of Odisha. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ Hammarström (2015) Ethnologue 16/17/18th editions: a comprehensive review: online appendices

- ^ "Odia". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 September 2024. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "The Constitution (Ninety-Sixth Amendment) Act, 2011". eGazette of India. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ "Odisha Name Alteration Act, 2011". eGazette of India. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- ^ Mahapatra, B. P. (2002). Linguistic Survey of India: Orissa (PDF). Kolkata, India: Language Division, Office of the Registrar General. p. 14. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "Ordeal of Oriya-speaking students in West Bengal to end soon". The Hindu. 21 May 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "Govt to provide study facility to Odia-speaking people in State". The Pioneer. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ^ "Classical Language: Odia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "Odia gets classical language status". The Hindu. 20 February 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ^ "Odia becomes sixth classical language". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Milestone for state as Odia gets classical language status". The Times of India. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ Pattanayak, Debi Prasanna; Prusty, Subrat Kumar. Classical Odia (PDF). Bhubaneswar: KIS Foundation. p. 54. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ a b (Toulmin 2006:306)

- ^ Misra, Bijoy (11 April 2009). Oriya Language and Literature (PDF) (Lecture). Languages and Literature of India. Harvard University.

- ^ "Odia Language". Odisha Tourism. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ a b Tripathī, Kunjabihari (1962). The Evolution of Oriya Language and Script. Utkal University. pp. 29, 222. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ (Rajaguru 1966:152)

- ^ B. P. Mahapatra (1989). Constitutional languages. Presses Université Laval. p. 389. ISBN 978-2-7637-7186-1.

Evidence of Old Oriya is found from early inscriptions dating from the 10th century onwards, while the language in the form of connected lines is found only in the inscription dated 1249 A.D.

- ^ a b Patnaik, Durga (1989). Palm Leaf Etchings of Orissa. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. p. 11. ISBN 978-81-7017-248-2.

- ^ a b Panda, Shishir (1991). Medieval Orissa: A Socio-economic Study. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 106. ISBN 978-81-7099-261-5.

- ^ a b Patnaik, Nihar (1997). Economic History of Orissa. New Delhi: Indus Publishing. p. 149. ISBN 978-81-7387-075-0.

- ^ Sukhdeva (2002). Living Thoughts of the Ramayana. Jaico Publishing House. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-7992-002-2.

- ^ Sujit Mukherjee (1998). A Dictionary of Indian Literature: Beginnings-1850. Orient Blackswan. p. 420. ISBN 978-81-250-1453-9.

- ^ Mallik, Basanta Kumar (2004). Paradigms of Dissent and Protest: Social Movements in Eastern India, C. AD 1400-1700. Manohar Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 978-81-7304-522-6.

- ^ Pritish Acharya, "Nationalistic Politics: Nature, Objectives and Strategy." From Late 19th Century to Formation of UPCC", in Culture, Tribal History and Freedom Movement, ed. P.K. Mishra, Delhi: Agam Kala Prakasham, 1989

- ^ Sachidananda Mohanty, "Rebati and the Woman Question in Odisha", India International Centre Quarterly, New Delhi, Vol. 21, No.4, Winter 1994

- ^ a b c "C-16: Population by mother tongue, India - 2011". Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India.

- ^ "Number of Odia speaking people declines: Census report". sambad. 18 July 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ James Minahan (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-59884-659-1.

- ^ "A Little Orissa in the heart of Surat – Ahmedabad News". The Times of India. 18 May 2003. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ Danesh Jain; George Cardona (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 445. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- ^ "Oriya language". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

Oriya language, also spelled Odia, Indo-Aryan language with some 50 million speakers.

- ^ a b Institute of Social Research and Applied Anthropology (2003). Man and Life. Vol. 29. Institute of Social Research and Applied Anthropology. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ Subhakanta Behera (2002). Construction of an identity discourse: Oriya literature and the Jagannath cult (1866–1936). Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ "Mughalbandi". Glottolog.

- ^ "LSI Vol-5 part-2". dsal. pp. 369, 382.

- ^ "Northwestern Oriya". Glottolog.

- ^ "LSI Vol-5 part-2". dsal. p. 403.

- ^ Mathai & Kelsall 2013, pp. 4–6. The precise figures are 75–76%. This was based on comparisons of 210-item wordlists.

- ^ "Sambalpuri". Ethnologue.

- ^ a b

CENSUS OF INDIA 2011. "LANGUAGE" (PDF). Government of India. p. 7.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Midnapore Oriya". Glottolog.

- ^ "Bhatri". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ Masica (1991:16)

- ^ Rabindra Nath Pati; Jagannatha Dash (2002). Tribal and Indigenous People of India: Problems and Prospects. New Delhi: APH PUBLISHING CORPORATION. pp. 51–59. ISBN 81-7648-322-2.

- ^ a b c Ray (2003:526)

- ^ Cardona, George; Jain, Danesh (2003). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 488. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- ^ a b Neukom, Lukas; Patnaik, Manideepa (2003)

- ^ Ray (2003:488–489)

- ^ Masica (1991:107)

- ^ Danesh Jain; George Cardona (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 490. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- ^ Masica (1991:147)

- ^ Ray (2003:490–491)

- ^ Jain, D.; Cardona, G. (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge language family series. Taylor & Francis. p. 450. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Caldwell, R. (1998). A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Or South-Indian Family of Languages. Asian Educational Services. p. 125. ISBN 978-81-206-0117-8. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections. Sahitya Akademi. 1 January 1997. ISBN 978-81-260-0365-5.

- ^ Biswamoy Pati Situating social history: Orissa, 1800–1997 p30

- ^ The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature (Volume Two) (Devraj To Jyoti): 2 p1030 ed. Amaresh Datta – 2006 "Amos Sutton also prepared a dictionary named Sadhu bhasharthabhidhan, a vocabulary of current Sanskrit terms with Odia definitions which was also printed in Odisha Mission Press in 1844."

- ^ Statt, Nick (26 February 2020). "Google Translate supports new languages for the first time in four years, including Uyghur". The Verge. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ "Odia Language Text Translation is Now Available in Microsoft Translator". Microsoft. 13 August 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Mathai, Eldose K.; Kelsall, Juliana (2013). Sambalpuri of Orissa, India: A Brief Sociolinguistic Survey (Report). SIL Electronic Survey Reports.

- Rajaguru, Satyanarayan (1966). Inscriptions of Orissa C. 600–1100 A.D. Vol. 2. Government of Orissa, Superintendent of Research & Museum.

- Ray, Tapas S. (2003). "Oriya". In Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 485–522. ISBN 978-0-7007-1130-7.

- Toulmin, Matthew William Stirling (2006). Reconstructing linguistic history in a dialect continuum: The Kamta, Rajbanshi, and Northern Deshi Bangla subgroup of Indo-Aryan (PhD dissertation). The Australian National University. doi:10.25911/5d7a2b0c76304. hdl:1885/45743.

Further reading

[edit]- Ghosh, Arun (2003). An ethnolinguistic profile of Eastern India: a case of South Orissa. Burdwan: Dept. of Bengali (D.S.A.), University of Burdwan.

- Masica, Colin (1991). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Mohanty, Prasanna Kumar (2007). The History of: History of Oriya Literature (Oriya Sahityara Adya Aitihasika Gana).

- Neukom, Lukas; Patnaik, Manideepa (2003). A Grammar of Oriya. Arbeiten des Seminars für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Zürich. Vol. 17. Zurich: University of Zurich. ISBN 978-3-9521010-9-4.

- "Oriya Language and Literature" (PDF). Odia.org. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Rabindra Nath Pati; Jagannatha Dash (2002). Tribal and Indigenous People of India: Problems and Prospects. India: APH PUBLISHING CORPORATION. pp. 51–59. ISBN 81-7648-322-2.

- Tripathi, Kunjabihari (1962). The Evolution of Oriya Language and Script (PDF). Cuttack: Utkal University. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

External links

[edit] Media related to Odia language at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Odia language at Wikimedia Commons- Odia Wikipedia

- Praharaj, G.C. Purnachandra Odia Bhashakosha Archived 5 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine (Odia-English dictionary). Cuttack: Utkal Sahitya Press, 1931–1940.

- A Comprehensive English-Oriya Dictionary (1916–1922)