Basil Hood

Basil Willett Charles Hood (5 April 1864 – 7 August 1917) was a British dramatist and lyricist, perhaps best known for writing the libretti of half a dozen Savoy Operas and for his English adaptations of operettas, including The Merry Widow.

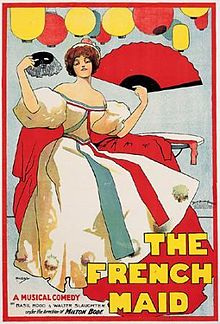

He embarked on a career in the British Army, rising to the rank of captain, while writing theatrical pieces in his spare time. After some modest success, Hood and his collaborator, the composer Walter Slaughter, had a major hit with their long-running show, Gentleman Joe, in 1895. Another long-running success was The French Maid (1896). Hood then resigned from the army to pursue his career as a librettist full-time. With Arthur Sullivan and then Edward German, he wrote several well-received pieces for the Savoy Theatre, including The Rose of Persia (1899), The Emerald Isle (1901), Merrie England (1902) and A Princess of Kensington (1903).

After comic opera went out of fashion, Hood turned to Edwardian musical comedy, writing lyrics for The Belle of Mayfair (1906) and The Girls of Gottenberg (1907), among others. He then found his greatest success with adaptations of continental operettas for the impresario George Edwardes, writing English versions of such works as (1907), The Dollar Princess (1908), A Waltz Dream (1908) and The Count of Luxembourg (1911), among others, sometimes drastically rewriting the book and lyrics. At the outbreak of World War I, he took up a demanding post in the British War Office, which is believed to have contributed to his early death.

Life and works

[edit]Early life and military career

[edit]Hood was born in Croydon, Surrey, the youngest of nine children of the psychiatrist Sir William Charles Hood (1824–1870), M.D., who was superintendent, physician and treasurer to Bethlem Royal Hospital and later a Commissioner in Lunacy.[1] His mother was Jane née Willett (1826–1866).[2] After both parents died in his early childhood, Hood was raised by his older siblings[2] and educated at Wellington and Sandhurst. He was commissioned a lieutenant in the Green Howards in 1883.[3] In 1887, he married Frances Ada née English (1866–1922), but two months later she was institutionalised at Bethlem Royal Hospital, and she remained in asylums until her death.[2] He was promoted to captain in 1893 and retired in 1895, but joined the 3rd (Militia) Battalion later the same year. He resigned his commission in 1898.[3] A courteous gentleman, Hood was well-liked; he was also generous with money and a poor businessman.[4]

Early stage works

[edit]Hood began writing for the theatre in his mid-twenties. His first one-act piece, The Gypsies, with music by Wilfred Bendall, was mounted as a curtain-raiser at the Prince of Wales Theatre in 1890. The Times praised the piece and remarked on "a certain flavour of Gilbertian paradox".[5] Hood provided the lyrics to Lionel Monckton's song, "What Will You Have to Drink?", interpolated into the Gaiety Theatre burlesque Cinder Ellen up too Late in 1892.[6] Hood then wrote two short operettas with music by Walter Slaughter. The first was Donna Luiza,[7] which The Times again compared to W. S. Gilbert's work, this time less favourably.[8] The second piece by Hood and Slaughter was The Crossing Sweeper, presented at the Gaiety Theatre, with Kate Cutler and Florence Lloyd.[9]

In 1895, Hood and Slaughter wrote a full-length musical comedy, Gentleman Joe, the Hansom Cabbie, a vehicle for the comedian Arthur Roberts. It ran for 391 performances in London, with a second company also presenting it in the provinces.[10] Its success prompted Hood to resign his army commission to concentrate on his writing,[11] though he rejoined for three more years while continuing to write.[3] With Slaughter and B. C. Stephenson, Hood then wrote Belinda, which was produced in Manchester and described by The Manchester Guardian as "childish beyond precedent".[12] Another provincial piece with Slaughter, in 1897, was The Duchess of Dijon, in Portsmouth.[4] The next Slaughter and Hood success, The French Maid, won good reviews on its pre-London production[13] and from the London critics when it opened at Terry's Theatre in April 1897.[14] During the run, Hood wrote a short curtain raiser, Apron Strings, a farcical comedy about marital misunderstandings, which was added to the bill in October.[15] The French Maid transferred to the Vaudeville Theatre with revised music and lyrics,[16] running for 480 performances in all.[4][17] The collaborators followed it with five more shows in succession, including Her Royal Highness; Orlando Dando, the Volunteer (a vehicle for Dan Leno);[17] and another successful vehicle for Roberts, Dandy Dan, the Lifeguardsman (1897).[18] Also beginning in 1897, Hood and Slaughter wrote a series of short musicals for children, based on fairy tales, which received warm reviews, including Little Hans Andersen.[19][20][21] Hood developed a reputation for clever lyrics but convoluted plots.[4]

Librettist of Savoy Operas

[edit]After Arthur Sullivan finished collaborating with W. S. Gilbert (The Grand Duke, in 1896, was their last joint work), Richard D'Oyly Carte, the proprietor of the Savoy Theatre, looked for other librettists to provide librettos for Sullivan to set. Hood was introduced to Sullivan by his old collaborator Wilfred Bendall, who was then Sullivan's secretary.[22] Sullivan's several operas written in the 1890s without Gilbert had not been successful,[23] but his new opera with Hood, The Rose of Persia (1899), ran for 213 performances.[24] Hood also wrote the libretti for two short companion pieces at the Savoy. The first was Pretty Polly, which ran with The Rose of Persia in 1900 and with Patience in 1900–01,[25] and the second was Ib and Little Christina (1900), which played in several theatres including the Savoy (in 1901, as a companion piece to Hood's The Willow Pattern).[26] Hood also wrote such plays, during this period, as The Great Silence, with Louie Pounds (Coronet Theatre, London; 1900),[27] which was presented together with Cox and Box (starring Courtice Pounds as Box) and Ib and Little Christina, with Louie Pounds as adult Christina (otherwise, the original cast reprised their roles).[28]

After the success for Hood and Sullivan of The Rose of Persia, the pair were soon writing a second opera, The Emerald Isle (1901). Sullivan died while writing this new work, however, and the task of completing it fell to Edward German. The production was another reasonable success, with 205 performances.[26] Hood wrote that, at the time of Sullivan's death, he and Sullivan had also begun work on a serious opera.[4] Hood and German went on to collaborate on the successful Merrie England (1902), which played at the Savoy for 120 performances, toured the provinces for 14 weeks, and then returned for another run at the Savoy.[29] Of Merrie England, The Observer wrote, "It is not too much to say that Capt. Basil Hood and Mr. Edward German have, by means of the latest Savoy success, increased their reputations to an extent that will lead the musical public to look to them in future for work as epoch-making in its peculiar genre as that of Gilbert and Sullivan. Capt. Hood is the only writer of "words for music" whose lyrics can compare with those of Mr. Gilbert for finish, rhythmic piquancy, and verbal quaintness."[30] Another piece in 1902, My Pretty Maid, starring Edward Terry, lasted less than two months.[4] When Merrie England finished its second London run, German and Hood immediately followed it with A Princess of Kensington (1903) which ran for 115 performances and then went on tour. After that, their producer, William Greet, turned away from light opera, which effectively ended their work together.[6]

Adapter of operettas

[edit]

Between 1903 and 1906, Hood worked on several musical comedies, including one based on Romeo and Juliet, but when producer Charles Frohman started altering his work to suit casting considerations, he withdrew his name from the book of what was produced with great success as The Belle of Mayfair (1906), although he remained credited with some lyrics. He also revived Little Hans Andersen at the Adelphi Theatre, in 1903, and adapted Victorien Sardou's play Les Merveilleuses as the libretto for George Edwardes's musical at Daly's Theatre, The Merveilleuses (1906). Next, he supplied the Gaiety Theatre with lyrics for the successful musical The Girls of Gottenberg (1907).[4][6]

With the resurgence of interest in Continental European operettas, Edwardes engaged Hood to prepare the English versions of what became a series of extremely successful productions. Critical opinion has differed about this period of Hood's career. The Times, in its obituary notice, wrote, "He spent more ability in adapting librettos for the late George Edwardes than the quality of the work demanded … under these conditions he scarcely fulfilled his promise as a wit and poet.[31] By contrast, in the view of the Encyclopedia of Popular Music, "adapting German and Viennese operettas … is where he found his métier. Often discarding the original premise, he helped create lively and very popular operettas."[11] Hood generally changed the structure of these works from three acts to two, often greatly re-writing them and adapting the plots.[4] Shows that Hood adapted included the tremendously popular London production of The Merry Widow (1907); another hit, The Dollar Princess (1908); A Waltz Dream (1908); another success, The Count of Luxembourg (1911), and the also popular Gypsy Love (1912).

Hood's original works were few in these years. In 1909, his Little Hans Andersen was revived under the management of William Greet. In 1913 he wrote his last musical comedy success, The Pearl Girl, with Howard Talbot.[4][6] In 1912, the actor-manager Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree proposed another collaboration between Hood and German to provide a musical production based on the life of Sir Francis Drake, but German declined the commission.[32]

Last years

[edit]With the outbreak of World War I, German-language operetta lost its popularity. After that, Hood supplied lyrics for individual numbers for some musicals, and a revue, Bric-a-Brac with Lionel Monckton and Arthur Wimperis, and some non-musical plays. In the early days of the war, he took up a post with the Cryptography Division of the War Office.[4][33] Despite the heavy demands of his wartime work, he wrote a patriotic light opera, Young England, with music by G. H. Clutsam and Hubert Bath, starring Walter Passmore, which ran at Daly's Theatre and then the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1916–17 before going on tour.[34] In his final years, Hood developed an obsession with Shakespeare's Hamlet, which he believed contained a cryptogram that he worked to decipher. His companion of later years was Doris Armine Ashworth; she died about 1958.[4]

Hood died suddenly in his flat in St. James's Street, London, at the age of 53, from the effects of overwork and neglecting to eat.[35] After his death, his children's book, Saint George of England, was published in 1919 by George G. Harrap & Co., London.[4]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Daily News, 13 July 1868, p. 5; and "The Dundee Courier", 18 July 1868, p. 3

- ^ a b c Smith, J. Donald. "Who Was Basil Hood? – Part I", Sir Arthur Sullivan Society Magazine, No. 84, Spring 2014, pp. 26–35

- ^ a b c "Obituary, Captain Basil Hood", The Manchester Guardian, 8 August 1917, p. 3

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Smith, J. Donald. "Who Was Basil Hood? – Part II", Sir Arthur Sullivan Society Magazine, No. 85, Summer 2014, pp. 15–32

- ^ "Prince of Wales's Theatre," The Times, 27 October 1890, p. 8

- ^ a b c d Basil Hood biography at the British Musical Theatre website of the Gilbert and Sullivan archive, 31 August 2004, adapted from The Encyclopedia of the Musical Theatre by Kurt Gänzl. Retrieved 11 June 2010

- ^ The Observer, 27 March 1892, p. 6

- ^ "Prince of Wales's Theatre", The Times, 24 March 1892, p. 9

- ^ The Observer, 16 April 1893, p. 6

- ^ The Manchester Guardian, 25 August 1895, p. 5

- ^ a b Larkin, Colin (ed). " Hood, Basil", Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Muze Inc and Oxford University Press, Inc. 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2010 (requires subscription)

- ^ The Manchester Guardian, 6 October 1896, p. 5

- ^ The Manchester Guardian, 24 November 1896, p. 5

- ^ "Terry's Theatre," The Observer, 25 April 1897, p. 6.

- ^ The Observer, 10 October 1897, p. 6.

- ^ The Observer, 13 February 1898, p. 6

- ^ a b The Observer, 7 August 1898, p. 6

- ^ Adams, pp. 374 and 431

- ^ "Terry's Theatre", The Times, 24 December 1897, p. 6

- ^ "The Happy Life, by Louis N. Parker, to be Produced at the Duke of York's Theatre", The New York Times, 5 December 1897

- ^ "The Tinder Box and Little Claus and Big Claus", The Observer, 21 November 1897, p. 6

- ^ Wilson, Fredric Woodbridge. "Hood, Basil", Grove Music Online. Retrieved 13 June 2010 (requires subscription)

- ^ The Chieftain, with F. C. Burnand ran for 97 performances in 1894–95, and The Beauty Stone with Arthur Wing Pinero and J. Comyns Carr ran for 50 performances in 1898: see Rollins and Witts, pp. 15–18

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 18

- ^ Pretty Polly: Reviews reproduced from The Pall Mall Gazette etc. at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 8 May 2008. Retrieved 11 June 2010

- ^ a b Rollins and Witts, p. 19

- ^ Adams, p. 606

- ^ "The Coronet Theatre", The Morning Post, 25 July 1900, p. 3

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 20

- ^ The Observer, 6 April 1902, p. 6

- ^ Obituary, The Times, 8 August 1917, p. 9

- ^ McDonald, Tim. "Edward German (1862 –1936)", Naxos, 1992. Retrieved 11 October 2014

- ^ Kenrick, John. "Who's Who in Musicals: Additional Bios XII", Musicals101.com, 2004. Retrieved 11 June 2010

- ^ "Young England: Music and Laughter at Daly's", The Times, 26 December 1916, p. 9; The Times 4 January 1917, p. 8; and 26 March 1917, p. 11

- ^ "Captain Basil Hood's Death: Excessive Concentration on Cryptograms", The Times, 11 August 1917; p. 3

References

[edit]- Rollins, Cyril; R. John Witts (1962). The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas: A Record of Productions, 1875–1961. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 504581419.

External links

[edit]- 1864 births

- 1917 deaths

- 19th-century British Army personnel

- British Militia officers

- English male dramatists and playwrights

- English opera librettists

- Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

- Green Howards officers

- Military personnel from the London Borough of Croydon

- People associated with Gilbert and Sullivan

- People educated at Wellington College, Berkshire

- People from Croydon