Nicholas Ridley, Baron Ridley of Liddesdale

The Lord Ridley of Liddesdale | |

|---|---|

1978 portrait, from the National Portrait Gallery collection | |

| Secretary of State for Trade and Industry | |

| In office 24 July 1989 – 14 July 1990 | |

| Prime Minister | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | The Lord Young of Graffham |

| Succeeded by | Peter Lilley |

| Secretary of State for the Environment | |

| In office 21 May 1986 – 24 July 1989 | |

| Prime Minister | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | Kenneth Baker |

| Succeeded by | Chris Patten |

| Secretary of State for Transport | |

| In office 16 October 1983 – 21 May 1986 | |

| Prime Minister | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | Tom King |

| Succeeded by | John Moore |

| Financial Secretary to the Treasury | |

| In office 14 September 1981 – 16 October 1983 | |

| Prime Minister | Margaret Thatcher |

| Preceded by | Nigel Lawson |

| Succeeded by | John Moore |

| Member of the House of Lords | |

| Life peerage 28 July 1992 – 4 March 1993 | |

| Member of Parliament for Cirencester and Tewkesbury | |

| In office 8 October 1959 – 16 March 1992 | |

| Preceded by | William Morrison |

| Succeeded by | Geoffrey Clifton-Brown |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Nicholas Ridley 17 February 1929 Northumberland, England |

| Died | 4 March 1993 (aged 64) Carlisle, Cumbria, England |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse |

Clayre Campbell

(m. 1950; div. 1974) |

| Children | 3 (including Jane) |

| Parent | The 3rd Viscount Ridley (father) |

| Relatives | The 4th Viscount Ridley (brother) Elisabeth Lutyens (aunt) Mary Lutyens (aunt) |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford |

| Part of the politics series on |

| Thatcherism |

|---|

|

Nicholas Ridley, Baron Ridley of Liddesdale, PC (17 February 1929 – 4 March 1993), was a British Conservative Party politician and government minister.

As President of the Selsdon Group, a free-market lobby within the Conservative Party, he was closely aligned with Margaret Thatcher, and became one of her Ministers of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in 1979. Responsible for the Falkland Islands, he tried to resolve the long-running sovereignty issue with Argentina, which detected Britain's reluctance to defend the territory, and later invaded it.

As Secretary of State for Transport, Ridley performed a key function in building up coal stocks in advance of the 1984–85 miners' strike, which helped the government to defeat the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM).

As Secretary of State for the Environment, Ridley opposed a low-cost housing development near his own property, earning him the title of "NIMBY" ("Not in My Back Yard"). He was also responsible for introducing the "poll tax" (formally known as the Community Charge), which was one of the main factors leading to Thatcher's resignation in 1990. He was created a life peer in 1992.

Background and education

[edit]Ridley was the second son of Matthew White Ridley, 3rd Viscount Ridley, and Ursula (née Lutyens), daughter of architect Sir Edwin Lutyens. His elder brother was Matthew White Ridley, 4th Viscount Ridley. He was educated at West Downs School, Winchester, Eton College and Balliol College, Oxford, where he gained a third in mathematical moderations in 1947 and a second-class degree in engineering science in 1951.[1]

A contemporary at Eton was Tam Dalyell, later Labour MP for West Lothian. The two men were not even able to agree on whether or not Dalyell had been Ridley's fag, though Dalyell greatly admired Ridley's skills as an artist, quoting his teacher as saying that Ridley was "more talented than his grandfather" Edwin Lutyens.[2]

Ridley held a national service commission as a lieutenant in the 1st Battalion of The Loyal Regiment in 1947 and was later a Territorial Army captain in the Northumberland Hussars Yeomanry.[3] He later became a civil engineer and company director.

Political career, 1955–1979

[edit]At the 1955 general election, Ridley unsuccessfully contested the safe Labour seat of Blyth.[4] He was elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Cirencester and Tewkesbury at the 1959 election.[4] He was appointed as Parliamentary Private Secretary in 1962, and from 1964 he was a Select committee member before joining the front bench.

Ridley was made a parliamentary secretary in the Ministry of Technology briefly in 1970 before becoming a Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State in the Department of Trade and Industry.[4] He came under pressure after a policy report he had authored in December 1969 on the break-up and privatisation of Upper Clyde Shipbuilders was leaked, where he had proposed that a Conservative government should cut up and "butcher" UCS and sell the government's holdings, "even for a pittance".[5][6]

He left the government in 1972 after refusing the post of Arts Minister.[4] Ridley told Patrick Cosgrave a few days later that "Ted [Heath] thought that because I drew and painted things, I would like to be Minister for the Arts. I had to explain to him that the ministry should not exist, because it involved public expenditure".[4]

In 1973, he co-founded the Selsdon Group, which was opposed to the abandonment of the radical 1970 manifesto by Edward Heath. He closed his keynote speech at the group's launch by citing the "Ten Cannots" of William J. H. Boetcker, adding that they "could well become the guiding principle of the Selsdon Group".[7] The members of the group were seen as disloyal at the time but their ideas came to prominence in the Thatcher years.

In government, 1979–1990

[edit]When the Conservatives were returned to office at the 1979 general election, Ridley was appointed to the new Conservative government as Minister of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. In this position he was assigned responsibility for policy concerning the Falkland Islands, a position in which according to Patrick Cosgrave, he did not acquit himself well and "seriously misread the intentions of the Argentinian government".[4] His first visit to the Islands was in July 1979, after which the Foreign Office considered the options, given that the idea of 'Fortress Falklands' was deemed unfeasible on the grounds of cost – Britain could not afford to maintain a sufficiently powerful military presence on the Islands to deter an invasion.

Ridley held a secret, informal meeting with his Argentine opposite number Carlos Cavandoli in September 1980, and the two sides broadly agreed to a "leaseback" arrangement whereby nominal sovereignty would be given to Argentina but British administration would be maintained for a fixed number of years, likely 99, until the final handover, as well as co-operating on the Islands' economic development and exploitation of fish and potential oil resources. The meeting took place at a village hotel ten miles outside Geneva, Switzerland, under the pretext of a holiday for Ridley and his wife, so as to avoid Parliamentary and media accusations of a sell-out.[8] Ridley returned to the Islands in November to try to persuade the Islanders to accept the proposal but they were unconvinced, and as he left islanders shouted abuse at him while playing a recording of "Rule, Britannia!". A prominent local islands politician, Adrian Monk, also made what the then Governor of the islands, Sir Rex Hunt, described as a 'Churchillian' explanation of the population's views in a Falklands radio broadcast on 2 January 1981.[9] Likewise, Parliament gave the proposals a hostile reception, pointing out that British people should not be transferred, against their wishes, to the control of an Argentine military junta which had committed multiple human rights violations.[10] In the face of this opposition, the Conservative government once again reiterated that the Islanders' wishes were 'paramount'.

In February 1981, with the support of the Islands' Councillors, the British government met Argentine representatives in New York but the British proposal for a sovereignty freeze was rejected by the junta. British intelligence reports continued to suggest that Argentina would invade the Islands only if it was convinced there was no prospect of eventual transfer of sovereignty.

Ridley advised that leaseback remained the only feasible solution and recommended that Britain initiate an education campaign to persuade the islanders. His fierce political opponent Tam Dalyell believed he was right and that but for Ridley's "confrontational style", "off-handed and offensive disdain" which upset both the islanders and the House of Commons, this policy could have avoided the war.[2] The proposal was rejected by Lord Carrington who felt that any attempt to put pressure on Islanders would be counter-productive. However, the cumulative effect of stalled sovereignty negotiations, the British Nationality Act 1981 (which would deprive many Islanders of their rights as full British citizens), the announced withdrawal of HMS Endurance, the shelving of plans to rebuild the Royal Marine barracks at Moody Brook, and the proposed closure of the British Antarctic Survey base at Grytviken on South Georgia, was to convince Argentina that Britain had no future interest in the Falkland Islands.[citation needed] Argentina invaded the islands in April 1982, beginning the Falklands War, but was repulsed in June of that year, with the islands remaining in British hands.

Financial Secretary to the Treasury

[edit]From 1981 to 1983 Ridley was the Financial Secretary to the Treasury.

Secretary of State for Transport

[edit]Following the 1983 election, Ridley, always regarded by Margaret Thatcher as "one of us", was a beneficiary of her move to cull the Tory wets and joined her cabinet as Secretary of State for Transport. In that role he played a major part in making preparations for a potential loss of coal supplies, which proved an important factor in deciding the outcome of the miners' strike. Ridley had long been acutely aware of the threat the trade unions could pose to the execution of Conservative policies and, in the wake of the Heath government's union difficulties, had authored the Ridley Plan, which set out means of dealing with the trade unions and was a prototype for later developments. The Thatcher government attached considerable importance to being properly prepared for a major miners' strike and backed down from a confrontation with the miners in its first Parliament. By the time that the miners did strike, from early March 1984, considerable efforts had been made in ensuring the availability of stockpiled coal at power stations, non-unionised transport workers and oil-fired generation plant.

He oversaw bus deregulation with the Transport Act 1985 as a precursor to privatisation of bus services. This led to a period of intense competition between rival bus companies, known at the time as the bus wars and the dramatic subsequent growth of Stagecoach Group, FirstGroup and the other major bus operators.

Never far from controversy, Ridley had to apologise following the Herald of Free Enterprise disaster in 1987, for remarking that he would not be pursuing a particular policy "with the bow doors open". The ship had capsized, with loss of 193 lives, as a result of sailing with its bow doors open.

Secretary of State for the Environment

[edit]As Secretary of State for the Environment from 1986 to 1989, he is credited with popularising the phrase NIMBY or Not in My Back Yard to describe those who instinctively opposed any local building development. It was soon revealed that Ridley opposed a low cost housing development near a village where he owned a property.[11] More importantly, he was the Cabinet Minister responsible for the introduction of the 'Poll tax' (formally known as the Community Charge), a policy that brought a standing ovation at the Conservative Party conference at which it was announced, and riots across the country when it was implemented. Ridley had reduced the implementation timetable from 5 to 2 years, which made it much easier for opponents to identify 'losers' and gain support for protest.[citation needed]

Secretary of State for Trade and Industry

[edit]On 14 July 1990, he was forced to resign as Secretary of State for Trade and Industry after an interview was published by The Spectator.[12] He had described the proposed Economic and Monetary Union as "a German racket designed to take over the whole of Europe" and said that giving up sovereignty to the European Union was as bad as giving it up to Adolf Hitler. The interview was illustrated with a cartoon depicting Ridley running away having added a Hitler moustache to a poster of the German Chancellor Helmut Kohl.[13] While Ridley was not one of the most powerful government members, he was regarded as a Thatcherite loyalist and his departure was a significant break in their ranks. Margaret Thatcher herself resigned a few months later. Some commentators point to Ridley's resignation, its manner, and the European issue at its core, as leading indicators for the next decade of Conservative Party politics. On 8 November 1991, Ridley advised people to vote for anti-European candidates regardless of their parties.[14]

Baron Ridley of Liddesdale

[edit]On 28 July 1992, Ridley was created a life peer as Baron Ridley of Liddesdale, of Willimoteswick in the County of Northumberland.[15] Despite being a free-marketeer, in January 1993 Ridley spoke out against railway privatisation, and when in government, advised Thatcher against doing so.[16] The final speech he gave was an address against the Maastricht Treaty on 17 February 1993 in the House of Lords,[17] which he had always vehemently opposed and voted against in 1991. In an article for The Times written days before he died, he suggested that the rich should be taxed more to help Britain out of the recession.[18]

At the 1996 Nicholas Ridley Memorial Lecture, Thatcher said of Ridley that,

Free-market economics was always Nick's passion. And he had a longer, better pedigree in that respect than most Thatcherites—or indeed I may add—than Thatcher herself. His first vote against a Conservative Government bailing out nationalised industries was in 1961. To be so right, so early on, is not to have seen the light—it is to have lit it ... He would have been a superb Chancellor.[19]

Ridley was also secretary of the Canning Club, a councillor on Castle Ward Rural District Council and a member of the executive committee of the National Trust.

Personal life

[edit]Lord Ridley of Liddesdale was married to Clayre Campbell, daughter of Alistair Campbell, 4th Baron Stratheden and Campbell. They divorced in 1974. They had three daughters: social worker Susanna Rickett, designer and writer Jessica Ridley, and historian Jane Ridley, Professor of History at the University of Buckingham. He was a keen water colourist and photographer.

In 1990, asked to comment on the resignation of his cabinet colleague Norman Fowler who had given as the reason for his resignation the wish "to spend more time with my family", Ridley quipped that the last thing he wanted to do was spend more time with his family.[20]

Ridley's puppet on Spitting Image was always portrayed with a cigarette.[citation needed] He died of lung cancer on 4 March 1993.

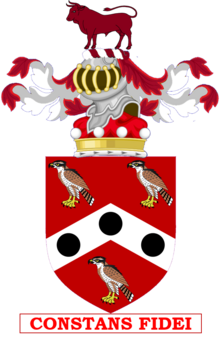

Arms

[edit]

|

|

References

[edit]- Footnotes

- ^ Patrick Cosgrave (January 2008). "Ridley, Nicholas, Baron Ridley of Liddesdale (1929–1993)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ a b Tam Dalyell (6 March 1993). "Obituary: Lord Ridley of Liddesdale". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Kelly's Handbook 1960. Kelly's. p. 1689.

- ^ a b c d e f Patrick Cosgrave (6 March 1993). "Obituary: Lord Ridley of Liddesdale". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Martin Holmes (1982). "3 - The U-Turn over industry policy". Political Pressure and Economic Policy: British Government 1970-1974. Butterworth Scientific. p. 42. ISBN 9780408108300.

- ^ "Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Volume 822: Columns 1089-1090". Hansard. 2 August 1971. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ "Conservatism: Nicholas Ridley speech at Selsdon Park (launch of Selsdon Group) | Margaret Thatcher Foundation". Margaretthatcher.org. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Freedman 2005, pp. 113–123

- ^ "DFB". www.falklandsbiographies.org.

- ^ Freedman 2005, pp. 124–132

- ^ "Would YOU live next to a Nimby?". BBC News. 21 May 2002. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Fineman, Mark (15 July 1990). "British Trade Minister Quits Post to End Furor : Europe: Ridley's insults against Germany and France brought cries of protest. Thatcher replaces him with a proponent of economic unity". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ^ From the archives: Ridley was right, The Spectator, 22 September 2011.

- ^ Thorpe, John. "Retro: Terry Waite free at last". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "No. 53006". The London Gazette. 31 July 1992. p. 12943.

- ^ "When will those trains run on time?". New Statesman. 2 January 2001. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "Maastricht Treaty (Hansard, 17 February 1993)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 17 February 1993. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ The Times, 3 March 1993.

- ^ "Nicholas Ridley Memorial Lecture (22 November 1996)". Margaretthatcher.org. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ "The Times & The Sunday Times". www.thetimes.co.uk.

- ^ "Life Peerages - R".

- Bibliography

- Freedman, Lawrence (2005). The Official History of the Falklands Campaign Vol. 1: The Origin of the Falklands War. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-5206-7.

External links

[edit]- 1929 births

- 1993 deaths

- Loyal Regiment officers

- Military personnel from Northumberland

- Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford

- British Secretaries of State for the Environment

- Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

- Conservative Party (UK) life peers

- Councillors in Northumberland

- Deaths from lung cancer in England

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- People educated at Eton College

- People educated at West Downs School

- Secretaries of state for transport (UK)

- Tobacco-related deaths

- UK MPs 1959–1964

- UK MPs 1964–1966

- UK MPs 1966–1970

- UK MPs 1970–1974

- UK MPs 1974

- UK MPs 1974–1979

- UK MPs 1979–1983

- UK MPs 1983–1987

- UK MPs 1987–1992

- Younger sons of viscounts

- Ridley family

- Northumberland Hussars officers

- Presidents of the Board of Trade

- Lutyens family

- Children of peers and peeresses created life peers

- Life peers created by Elizabeth II

- British Eurosceptics

- 20th-century British Army personnel