Barbie

The current Barbie logo | |

| Type | Fashion doll |

|---|---|

| Inventor(s) | Ruth Handler |

| Company | Mattel |

| Country | United States |

| Availability | March 9, 1959–present |

| Materials | Plastic |

| Official website | |

Barbie is a fashion doll created by American businesswoman Ruth Handler, manufactured by American toy and entertainment company Mattel and introduced on March 9, 1959. The toy was based on the German Bild Lilli doll which Handler had purchased while in Europe. The figurehead of an eponymous brand that includes a range of fashion dolls and accessories, Barbie has been an important part of the toy fashion doll market for over six decades. Mattel has sold over a billion Barbie dolls, making it the company's largest and most profitable line.[1] The brand has expanded into a multimedia franchise since 1984, including video games, animated films, television/web series, and a live-action film.

Barbie and her male counterpart, Ken, have been described as the two most popular dolls in the world.[2] Mattel generates a large portion of Barbie's revenue through related merchandise —accessories, clothes, friends, and relatives of Barbie. Writing for Journal of Popular Culture in 1977, Don Richard Cox noted that Barbie has a significant impact on social values by conveying characteristics of female independence, and with her multitude of accessories, an idealized upscale lifestyle that can be shared with affluent friends.[3]

History

Development

Ruth Handler watched her daughter Barbara play with paper dolls, and noticed that she often enjoyed giving them adult roles. At the time, most children's toy dolls were representations of infants. Realizing that there could be a gap in the market, Handler suggested the idea of an adult-bodied doll to her husband Elliot, a co-founder of the Mattel toy company. He was unenthusiastic about the idea, as were Mattel's directors.[4]

During a trip to Switzerland in 1956 with her children Barbara and Kenneth, Ruth Handler came across a German toy doll called Bild Lilli.[5][a] The adult-figured doll was exactly what Handler had in mind, so she purchased three of them. She gave one to her daughter and took the others back to Mattel. The Lilli doll was based on a popular character appearing in a satirical comic strip drawn by Reinhard Beuthin for the newspaper Bild.[6] The Lilli doll was first sold in West Germany in 1955, and although it was initially sold to adults, it became popular with children who enjoyed dressing her up in outfits that were available separately.[6][7]

Upon her return to the United States, Handler redesigned the doll (with help from local inventor-designer Jack Ryan) and the doll was given a new name, Barbie, after Handler's daughter Barbara. The doll made its debut at the American International Toy Fair in New York City on March 9, 1959.[8] This date is also used as Barbie's official birthday.

Launch

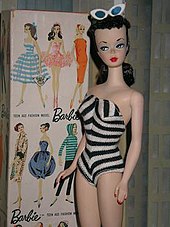

The first Barbie doll wore a black-and-white zebra striped swimsuit and signature topknot ponytail, and was available as either a blonde or brunette. The doll was marketed as a "Teen-age Fashion Model", with her clothes created by Mattel fashion designer Charlotte Johnson.[9]

Analysts expected the doll to perform poorly due to her adult appearance and widespread assumptions about consumer preferences at the time. Ruth Handler believed it was important for Barbie to have an adult appearance, but early market research showed that some parents were unhappy about the doll's chest, which had distinct breasts.[10]

Barbie sold about 350,000 units in her first year, beating market expectations and generating upside risk for investors. Sales of Barbie exceeded Mattel's ability to produce her for the first three years of her run. The market stabilized for the next decade while volume and margin increased by exporting refurbished dolls to Japan. Barbie was manufactured in Japan during this time, with her clothes hand-stitched by Japanese homeworkers.[11]

Louis Marx and Company sued Mattel in March 1961. After licensing Lilli, they claimed that Mattel had "infringed on Greiner & Hausser's patent for Bild-Lilli's hip joint", and also claimed that Barbie was "a direct take-off and copy" of Bild-Lilli. The company additionally claimed that Mattel "falsely and misleadingly represented itself as having originated the design". Mattel counter-claimed and the case was settled out of court in 1963. In 1964, Mattel bought Greiner & Hausser's copyright and patent rights for the Bild-Lilli doll for $21,600.[12][13]

Barbie's appearance has been changed many times, most notably in 1971 when the doll's eyes were adjusted to look forwards rather than having the demure sideways glance of the original model. This would be the last adjustment Ruth would make to her own creation as, three years later, she and her husband Elliot were removed from their posts at Mattel after an investigation found them guilty of issuing false and misleading financial reports.[10]

Barbie was one of the first toys to have a marketing strategy based extensively on television advertising, which has been copied widely by other toys. In 2006, it was estimated that over a billion Barbie dolls had been sold worldwide in over 150 countries, with Mattel claiming that three Barbie dolls are sold every second.[14]

Sales of Barbie dolls declined sharply from 2014 to 2016.[1] According to MarketWatch, the release of the 2023 film Barbie is expected to create "significant growth" for the brand until at least 2030.[15] As well as reinvigorated sales, the release of the film triggered a fashion trend known as "Barbiecore"[16] and a film-related cultural phenomena named Barbenheimer.

Appearances in media

Since 1984, in response to a rise of digital and interactive media and a gradual decline in toys and doll sales at that time, Barbie has been featured in an eponymous media franchise beginning with the release of two eponymous video games, one that year and another in 1991 and two syndicated television specials released in 1987; Barbie and the Rockers: Out of This World and its sequel. She then began to appear as a virtual actress in a series of direct-to-video animated feature films with Barbie in the Nutcracker in 2001,[17] which were also broadcast on Nickelodeon in the United States as promotional specials until 2017.[18] Since 2017, the film series were revamped as streaming television films, branded as animated "specials" and released through streaming media services, primarily on Netflix.[19][20][21]

At the time of the release of Barbie in the Pink Shoes on February 26, 2013, the film series have sold over 110 million units globally.[22] Since 2012, she has appeared in several television and web series; including Barbie: Life in the Dreamhouse, Barbie: Dreamtopia, Barbie: Dreamhouse Adventures, Barbie: It Takes Two and Barbie: A Touch of Magic. Aside in lead roles, she has appeared as a supporting character in the Toy Story films between its second and third sequels with a cameo at the fourth and the My Scene media franchise.[19] In 2015, Barbie began appearing as a vlogger on YouTube called Barbie Vlogger where she talks about her fictional life, fashion, friends and family, and even charged topics such as mental health and racism.[23][24][25] She was portrayed by Australian actress Margot Robbie in a live-action film adaptation[26] released on July 21, 2023, by Warner Bros. Pictures in the United States.[27]

Fictional biography

| Barbie | |

|---|---|

| First appearance | March 9, 1959 |

| Created by | Ruth Handler |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Barbara Millicent Roberts |

| Nickname | Barbie |

| Occupation | See: Barbie's careers |

| Family | See: List of Barbie's friends and family |

Barbie's full name is Barbara Millicent Roberts and her parents' names are given as George and Margaret Roberts from the fictional town of Willows, Wisconsin, in a series of novels published by Random House in the 1960s.[28][29] In those novels, Barbie attended Willows High School; while in the Generation Girl books, published by Golden Books in 1999, she attended the fictional Manhattan International High School in New York City (based on the real-life Stuyvesant High School).[30]

She has an on-off romantic relationship with her then-boyfriend Ken (full name "Kenneth Sean Carson"), who first appeared in 1961. A news release from Mattel in February 2004 announced that Barbie and Ken had decided to split up,[31] but in February 2006, they were hoping to rekindle their relationship after Ken had a makeover.[32] In 2011, Mattel launched a campaign for Ken to win Barbie's affections back.[33] The pair officially reunited in Valentine's Day 2011.[34] Beginning with Barbie Dreamhouse Adventures in 2018, the pair are seen as just friends or next-door neighbors until a brief return to pre-2018 aesthetics in the 2023 television show, Barbie: A Touch of Magic.

Mattel has created a range of companions and relatives for Barbie. She has three younger sisters: Skipper, Stacie, and Chelsea (named Kelly until 2011).[35] Her sisters have co-starred in many entries of the Barbie film series, starting with Barbie & Her Sisters in A Pony Tale from 2013. 'Retired' members of Barbie's family included Todd (twin brother to Stacie), Krissy (a baby sister), and Francie (cousin). Barbie's friends include Hispanic Teresa, Midge, African American Christie, and Steven (Christie's boyfriend). Barbie was also friendly with Blaine, an Australian surfer, during her split with Ken in 2004.[36]

Barbie has had over 40 pets including cats and dogs, horses, a panda, a lion cub, and a zebra. She has owned a wide range of vehicles, including pink Beetle and Corvette convertibles, trailers, and Jeeps. She also holds a pilot's license, and operates commercial airliners in addition to serving as a flight attendant. Barbie's careers are designed to show that women can take on a variety of roles in life, and the doll has been sold with a wide range of titles including Miss Astronaut Barbie (1965), Doctor Barbie (1988), and Nascar Barbie (1998).[37]

Legacy and influence

Barbie has become a cultural icon and has been given honors that are rare in the toy world. In 1974, a section of Times Square in New York City was renamed Barbie Boulevard for a week. The Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris at the Louvre held a Barbie exhibit in 2016. The exhibit featured 700 Barbie dolls over two floors as well as works by contemporary artists and documents (newspapers, photos, video) that contextualize Barbie.[38]

In 1986, the artist Andy Warhol created a painting of Barbie. The painting sold at auction at Christie's, London for $1.1 million. In 2015, The Andy Warhol Foundation then teamed up with Mattel to create an Andy Warhol Barbie.[39][40]

Outsider artist Al Carbee took thousands of photographs of Barbie and created countless collages and dioramas featuring Barbie in various settings.[41] Carbee was the subject of the 2013 feature-length documentary Magical Universe. Carbee's collage art was presented in the 2016 Barbie exhibit at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris in the section about visuals artists who have been inspired by Barbie.[42]

In 2013, in Taiwan, the first Barbie-themed restaurant called "Barbie Café" opened under the Sinlaku group.[43]

The Economist has emphasized the importance of Barbie to children's imagination:

From her early days as a teenage fashion model, Barbie has appeared as an astronaut, surgeon, Olympic athlete, downhill skier, aerobics instructor, TV news reporter, vet, rock star, doctor, army officer, air force pilot, summit diplomat, rap musician, presidential candidate (party undefined), baseball player, scuba diver, lifeguard, fire-fighter, engineer, dentist, and many more. [...] When Barbie first burst into the toy shops, just as the 1960s were breaking, the doll market consisted mostly of babies, designed for girls to cradle, rock and feed. By creating a doll with adult features, Mattel enabled girls to become anything they want.[44]

On September 7, 2021, following the debut of the streaming television film Barbie: Big City, Big Dreams on Netflix, Barbie joined forces with Grammy Award-nominated music producer, songwriter, singer and actress Ester Dean and Girls Make Beats – an organization dedicated to expanding the female presence of music producers, DJs and audio engineers – to inspire more girls to explore a future in music production.[45][46][47]

Mattel Adventure Park

In 2023, Mattel broke ground on a theme park near Phoenix, Arizona. The park is to open in 2024 and highlights Mattel's toys, including a Barbie Beach House, a Thomas & Friends themed ride, and a Hot Wheels go-kart race track.[48][49][50] The theme park will take place at the VAI Resort complex, located 15 miles (24 km) west of Phoenix, Arizona.[50]

50th anniversary

In 2009, to celebrate the franchise's 50th anniversary, a runway show was held in New York for the Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week.[51] The event showcased fashions contributed by fifty well-known haute couturiers including Diane von Fürstenberg, Vera Wang, Calvin Klein, Bob Mackie, and Christian Louboutin.[52][53]

Barbie Dream Gap Project

In 2019, Mattel launched the "Barbie Dream Gap Project" to raise awareness of the phenomenon known as the "Dream Gap": beginning at the age of five, girls begin to doubt their own intelligence, where boys do not. This leads to boys pursuing careers requiring a higher intelligence, and girls being underrepresented in those careers.[54] As an example, in the U.S., 33% of sitting judges are female. This statistic inspired the release of Judge Barbie in four different skin tones and hairstyles with judge robes and a gavel accessory.[54]

Thank You Heroes

In May 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Mattel announced a new line of career dolls modeled after the first responders and essential workers of 2020. For every doll purchased, Mattel donated a doll to the First Responders Children's Foundation.[55]

Habitat for Humanity

In February 2022, Mattel celebrated its 60-year anniversary of the Barbie Dreamhouse by partnering with Habitat for Humanity International. Mattel committed to taking on 60 projects, including new construction, home preservation, and neighborhood revitalization.[56]

Bad influence concerns

In July 1992, Mattel released Teen Talk Barbie, which spoke a number of phrases including "Will we ever have enough clothes?", "I love shopping!", and "Wanna have a pizza party?" Each doll was programmed to say four out of 270 possible phrases, so that no two given dolls were likely to be the same (the number of possible combinations is 270!/(266!4!) = 216,546,345). One of these 270 phrases was "Math class is tough!", which led to criticism from the American Association of University Women; about 1.5% of all the dolls sold said the phrase. The doll was often erroneously misattributed in the media as having said "Math is hard!"[57][58] In October 1992, Mattel announced that Teen Talk Barbie would no longer say "Math class is tough!", and offered a swap to anyone who owned a doll that did.[59]

In 2002, Mattel introduced a line of pregnant Midge (and baby) dolls, but this Happy Family line was quickly pulled from the market due to complaints that she promoted teen pregnancy, though Midge was supposed to be a married adult.[60]

In September 2003, the Middle Eastern country of Saudi Arabia outlawed the sale of Barbie dolls and franchises, stating that they did not conform to the ideals of Islam. The Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice warned, "Jewish Barbie dolls, with their revealing clothes and shameful postures, accessories and tools are a symbol of decadence to the perverted West. Let us beware of her dangers and be careful."[61] The 2003 Saudi ban was temporary.[62] In Muslim-majority nations, there is an alternative doll called Fulla, which was introduced in November 2003 and is equivalent to Barbie, but is designed specifically to represent traditional Islamic values. Fulla is not manufactured by Mattel (although Mattel still licenses Fulla dolls and franchises for sale in certain markets), and (as of January 2021) the "Jewish" Barbie brand is still available in other Muslim-majority countries including Egypt and Indonesia.[63] In Iran, the Sara and Dara dolls, which were introduced in March 2002, are available as an alternative to Barbie, even though they have not been as successful.[64]

In November 2014, Mattel received criticism over the book I Can Be a Computer Engineer, which depicted Barbie as personally inept at computers, requiring her two male friends complete all of the necessary tasks to restore two laptops after she accidentally infects her and her sister's laptop with a malware-laced USB flash drive, before ultimately getting credit for recovering her sister's school project.[65] Critics felt that the characterization of Barbie as a software designer lacking low-level technical skills was sexist, as other books in the I Can Be... series depicted Barbie as someone who was totally competent in those jobs and did not require outside assistance from others.[66] Mattel later removed the book from sale on Amazon in response to the criticism,[67] and the company released a "Computer Engineer Barbie" doll who was a game programmer rather than game designer.[67][68]

Diversity

"Colored Francie" made her debut in 1967, and she is sometimes described as the first African-American Barbie doll. However, she was produced using the existing head molds for the white Francie doll and lacked distinct African characteristics other than dark skin. The first African-American doll in the Barbie range is usually regarded as Christie, who made her debut in 1968.[70][71] Black Barbie was launched in 1980 but still had Caucasian features. In 1990, Mattel created a focus group with African-American children and parents, early childhood specialists, and clinical psychologist, Darlene Powell Hudson. Instead of using the same molds for the Caucasian Barbies, new ones were created. In addition, facial features, skin tones, hair texture, and names were all altered. The body shapes looked different, but the proportions were the same to ensure clothing and accessories were interchangeable.[72] In September 2009, Mattel introduced the So In Style range, which was intended to create a more realistic depiction of African-American people than previous dolls.[73]

Starting in 1980, it produced Hispanic dolls, and later came models from across the globe. For example, in 2007, it introduced "Cinco de Mayo Barbie" wearing a ruffled red, white, and green dress (echoing the Mexican flag). Hispanic magazine reports that:

[O]ne of the most dramatic developments in Barbie's history came when she embraced multi-culturalism and was released in a wide variety of native costumes, hair colors and skin tones to more closely resemble the girls who idolized her. Among these were Cinco De Mayo Barbie, Spanish Barbie, Peruvian Barbie, Mexican Barbie and Puerto Rican Barbie. She also has had close Hispanic friends, such as Teresa.[74]

Professor Emilie Rose Aguilo-Perez argued that over time, Mattel shifted from ambiguous Hispanic presentations in their dolls to one that is more assertive in its "Latinx" marketing and product labeling.[75]

Mattel has responded to criticisms pointing to a lack of diversity in the line.[76] In 2016, Mattel expanded the So In Style line to include seven skin tones, twenty-two eye colors, and twenty-four hairstyles. Part of the reason for this change was due to declining sales.[77] The brand now offers over 22 skin tones, 94 hair colors, 13 eye colors and five body types.[78]

Mattel teamed up with Nabisco to launch a cross-promotion Barbie doll with Oreo cookies in 1997 and 2001. While the 1997 release of the doll was only released in a white version, for the 2001 release Mattel manufactured both a white and a black version. The 2001 release Barbie Oreo School Time Fun was marketed as someone with whom young girls could play after class and share "America's favorite cookie". Critics argued that in the African American community, Oreo is a derogatory term meaning that the person is "black on the outside and white on the inside", like the chocolate sandwich cookie itself.[79]

In May 1997, Mattel introduced Share a Smile Becky, a doll in a pink wheelchair. Kjersti Johnson, a 17-year-old high school student in Tacoma, Washington with cerebral palsy, pointed out that the doll would not fit into the elevator of Barbie's $100 Dream House. Mattel announced that it would redesign the house in the future to accommodate the doll.[80]

In July 2024, Mattel released the first blind Barbie in collaboration with the American Foundation for the Blind.[81] Alongside this, the company also launched a black Barbie with Down syndrome.[81]

Role model Barbies

In March 2018, in time for International Women's Day, Mattel unveiled the "Barbie Celebrates Role Models" campaign with a line of 17 dolls, informally known as "sheroes", from diverse backgrounds "to showcase examples of extraordinary women".[82][83] Mattel developed this collection in response to mothers concerned about their daughters having positive female role models.[82] Dolls in this collection include Frida Kahlo, Patti Jenkins, Chloe Kim, Nicola Adams, Ibtihaj Muhammad, Bindi Irwin, Amelia Earhart, Misty Copeland, Helene Darroze, Katherine Johnson, Sara Gama, Martyna Wojciechowska, Gabby Douglas, Guan Xiaotong, Ava Duvernay, Yuan Yuan Tan, Iris Apfel, Ashley Graham and Leyla Piedayesh.[82] In 2020, the company announced a new release of "shero" dolls, including Paralympic champion Madison de Rozario,[84] and world four-time sabre champion Olga Kharlan.[85][86] In July 2021, Mattel released a Naomi Osaka Barbie doll as a part of the 'Barbie Role Model' series. Osaka originally partnered with Barbie two years earlier.[87] A month earlier, a Julie Bishop doll was released to acknowledge the former Australian politician,[88] as was one for general practitioner Kirby White for her work during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia.[89] In August 2021 a Barbie modelled after European Space Agency astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti was released.[90]

Collecting

The standard range of Barbie dolls and related accessories are manufactured to approximately 1/6 scale, which is also known as playscale.[91] The standard dolls are approximately 11+1⁄2 inches (29 cm) tall.

Mattel estimates that there are well over 100,000 avid Barbie collectors. Ninety percent are women, at an average age of 40, purchasing more than twenty Barbie dolls each year. Forty-five percent of them spend upwards of $1000 a year. Vintage Barbie dolls from the early years are the most valuable at auction, and while the original Barbie was sold for $3.00 in 1959, a mint boxed Barbie from 1959 sold for $3552.50 on eBay in October 2004.[92] On September 26, 2006, a Barbie doll set a world record at auction of £9,000 sterling (US$17,000) at Christie's in London. The doll was a Barbie in Midnight Red from 1965 and was part of a private collection of 4,000 Barbie dolls being sold by two Dutch women, Ietje Raebel and her daughter Marina.[93]

In recent years, Mattel has sold a wide range of Barbie dolls aimed specifically at collectors, including porcelain versions, vintage reproductions, and depictions of Barbie as a range of characters from film and television series such as The Munsters and Star Trek.[94][95] There are also collector's edition dolls depicting Barbie dolls with a range of different ethnic identities.[96] In 2004, Mattel introduced the Color Tier system for its collector's edition Barbie dolls including pink, silver, gold, and platinum, depending on how many of the dolls are produced.[97] In 2020, Mattel introduced the Dia De Los Muertos collectible Barbie doll, the second collectible released as part of the company's La Catrina line which was launched in 2019.[98]

Parodies and lawsuits

Barbie has frequently been the target of parody:

- Mattel sued artist Tom Forsythe over a 1999 series of photographs called Food Chain Barbie in which Barbie winds up in a blender.[99][100][101] Mattel lost the lawsuit and was forced to pay Forsythe's legal costs.[99]

- On the 25th episode of In Living Color, in December 1990, a Homey D. Clown sketch found HDC filling in for Santa Claus at a shopping mall. A little girl (Kelly Coffield) asks for a Malibu Barbie & Condominium playset; instead, "Homey Claus" gives her "Compton Carlotta" (a crude doll made of sticks and bottlecaps) with a slum-apartment (a milk carton). When the girl complains, Homey raises his signature blackjack and wishes her a Merry Christmas; taking the hint, she thanks him and hastily retires.

- In Latin America, notable controversies include a 2018 legal dispute involving the Panama-based Frida Kahlo Corporation's allegations that Frida Kahlo's great-niece in Mexico had wrongly licensed the Frida Kahlo trademark for the "Frida Kahlo Barbie" doll.[102]

- Mattel filed a lawsuit in 2004 in the U.S. against Barbara Anderson-Walley, a Canadian business owner whose nickname is Barbie, over her website, which sells fetish clothing.[103][104] The lawsuit was dismissed.[99]

- In 2011, Greenpeace parodied Barbie, calling on Mattel to adopt a policy for its paper purchases that would protect the rainforest. Four months later, Mattel adopted a paper sustainability policy.[105]

- Saturday Night Live aired a parody of the Barbie commercials featuring "Gangsta Bitch Barbie" and "Tupac Ken".[106] In 2002, the show also aired a skit, which starred Britney Spears as Barbie's sister Skipper.[107]

- In November 2002, a New York judge refused an injunction against the British-based artist Susanne Pitt, who had produced a "Dungeon Barbie" doll in bondage clothing.[108]

- Aqua's song "Barbie Girl" was the subject of the lawsuit Mattel v. MCA Records, which Mattel lost in 2002, with Judge Alex Kozinski saying that the song was a "parody and a social commentary".[109][110]

- Two commercials by automobile company Nissan featuring dolls similar to Barbie and Ken was the subject of another lawsuit in 1997. In the first commercial, a female doll is lured into a car by a doll resembling G.I. Joe to the dismay of a Ken-like doll, accompanied by Van Halen's "You Really Got Me".[111] In the second commercial, the "Barbie" doll is saved by the "G.I. Joe" doll after she is accidentally knocked into a swimming pool by the "Ken" doll to Kiss's "Calling Dr. Love".[112] The makers of the commercial said that the dolls' names were Roxanne, Nick and Tad. Mattel claimed that the commercial did "irreparable damage" to its products,[113][114] but settled.[115]

- In 1999, Canadian nude model Barbie Doll Benson was involved in a trademark infringement case over her domain name, BarbieBenson.com.[116]

- In 1993, a group calling itself the Barbie Liberation Organization secretly modified a group of Barbie dolls by implanting voice boxes from G.I. Joe dolls, then returning the Barbies to the toy stores from where they were purchased.[117][118]

- Malibu Stacy from The Simpsons 1994 episode "Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy".

- Savior Barbie refers to a satirical Instagram account. Savior Barbie is depicted as being in Africa where she runs an NGO that provides drinking water to locals and makes sure to provide footage that depicts her glorious acts of goodness. The account is likely to have inspired others such as "Hipster Barbie" and "Socality Barbie".[119][120]

Competition from Bratz dolls

In May 2001, MGA Entertainment launched the Bratz series of dolls, a move that gave Barbie her first serious competition in the fashion doll market. In 2004, sales figures showed that Bratz dolls were outselling Barbie dolls in the United Kingdom, although Mattel maintained that in terms of the number of dolls, clothes, and accessories sold, Barbie remained the leading brand.[121] In 2005, figures showed that sales of Barbie dolls had fallen by 30% in the United States, and by 18% worldwide, with much of the drop being attributed to the popularity of Bratz dolls.[122]

In December 2006, Mattel sued MGA Entertainment for $1 billion, alleging that Bratz creator Carter Bryant was working for Mattel when he developed the idea for Bratz.[123] On July 17, 2008, a federal jury agreed that the Bratz line was created by Carter Bryant while he was working for Mattel and that MGA and its chief executive officer Isaac Larian were liable for converting Mattel property for their own use and intentionally interfering with the contractual duties owed by Bryant to Mattel.[124] On August 26, the jury found that Mattel would have to be paid $100 million in damages. On December 3, 2008, U.S. District Judge Stephen Larson banned MGA from selling Bratz. He allowed the company to continue selling the dolls until the winter holiday season ended.[125][126] On appeal, a stay was granted by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit; the Court also overturned the District Court's original ruling for Mattel, where MGA Entertainment was ordered to forfeit the entire Bratz brand.[127][128]

Mattel Inc. and MGA Entertainment Inc. returned to court on January 18, 2011, to renew their battle over who owns Bratz, which this time included accusations from both companies that the other side stole trade secrets.[129] On April 21, 2011, a federal jury returned a verdict supporting MGA.[130] On August 5, 2011, Mattel was also ordered to pay MGA $310 million for attorney fees, stealing trade secrets, and false claims rather than the $88.5 million issued in April.[131]

In August 2009, MGA introduced a range of dolls called Moxie Girlz, intended as a replacement for Bratz dolls.[132]

Effects on body image

From the start, some have complained that "the blonde, plastic doll conveyed an unrealistic body image to girls."[133]

Criticisms of Barbie are often centered around concerns that children consider Barbie a role model and will attempt to emulate her. One of the most common criticisms of Barbie is that she promotes an unrealistic idea of body image for a young woman, leading to a risk that girls who attempt to emulate her will become anorexic. Unrealistic body proportions in Barbie dolls have been connected to some eating disorders in children.[134][135][136][137]

A standard Barbie doll is 11.5 inches (29 cm) tall, giving a height of 5 feet 9 inches (1.75 m) at 1/6 scale. Barbie's vital statistics have been estimated at 36 inches (91 cm) (chest), 18 inches (46 cm) (waist) and 33 inches (84 cm) (hips). According to research by the University Central Hospital in Helsinki, Finland, she would lack the 17 to 22 percent body fat required for a woman to menstruate.[138] In 1963, the outfit "Barbie Baby-Sits" came with a book titled How to Lose Weight which advised: "Don't eat!"[139] The same book was included in another ensemble called "Slumber Party" in 1965 along with a pink bathroom scale permanently set at 110 pounds (50 kg),[139] which would be underweight for a woman 5 feet 9 inches (1.75 m) tall.[140] Mattel said that the waist of the Barbie doll was made small because the waistbands of her clothes, along with their seams, snaps, and zippers, added bulk to her figure.[141] In 1997, Barbie's body mold was redesigned and given a wider waist, with Mattel saying that this would make the doll better suited to contemporary fashion designs.[142][143]

In 2016, Mattel introduced a range of new body types: 'tall', 'petite', and 'curvy', releasing them exclusively as part of the Barbie Fashionistas line. 'Curvy Barbie' received a great deal of media attention[144][145][146] and even made the cover of Time magazine with the headline "Now Can We Stop Talking About My Body?".[147] Despite the curvy doll's body shape being equivalent to a US size 4 in clothing,[144] some children reportedly regarded her as "fat".[147][148]

Although Barbie had been criticized for its unrealistic-looking "tall and petite" dolls, the company has been offering more dolls set to more realistic standards in order to help promote a positive body image.[149]

-

Barbie's waist has been widened in more recent versions of the doll.

-

Back cover of the vintage booklet titled How to Lose Weight, stating "Don't Eat!"

-

Bathroom scale from 1965, permanently set at 110 pounds (50 kg)

"Barbie syndrome"

"Barbie syndrome" is a term that has been used to depict the desire to have a physical appearance and lifestyle representative of the Barbie doll. It is most often associated with pre-teenage and adolescent girls but is applicable to any age group or gender. A person with Barbie syndrome attempts to emulate the doll's physical appearance, even though the doll has unattainable body proportions.[150] This syndrome is seen as a form of body dysmorphic disorder and results in various eating disorders as well as an obsession with cosmetic surgery.[151]

Ukrainian model Valeria Lukyanova has received attention from the press, due in part to her appearance having been modified based on the physique of Barbie.[152][153] She stated that she has only had breast implants and relies heavily on make up and contacts to alter her appearance.[154] Similarly, Lacey Wildd, an American reality television personality frequently referred to as "Million Dollar Barbie", has also undergone 12 breast augmentation surgeries to become "the extreme Barbie".[155]

Jessica Alves, prior to coming out as transgender, underwent over £373,000 worth of cosmetic procedures to match the appearance of Barbie's male counterpart, garnering her the nickname the "Human Ken Doll". These procedures have included multiple nose jobs, six pack ab implants, a buttock lift, and hair and chest implants.[154] Sporting the same nickname, Justin Jedlica, the American businessman, has also received multiple cosmetic surgeries to enhance his Ken-like appearance.

In 2006, researchers Helga Dittmar, Emma Halliwell, and Suzanne Ive conducted an experiment testing how dolls, including Barbie, affect self-image in young girls. Dittmar, Halliwell, and Ive gave picture books to girls age 5–8, one with photos of Barbie and the other with photos of Emme, a doll with more realistic physical features. The girls were then asked about their ideal body size. Their research found that the girls who were exposed to the images of Barbie had significantly lower self-esteem than the girls who had photos of Emme.[156] However, Benjamin Radford noted that the answer may not be this simple since this research also showed that the age of the girl was a significant factor in the influence the doll had on her self esteem.[157]

Notable designers

- Kitty Black Perkins, creator of Black Barbie

- Carol Spencer, Barbie fashion designer from 1963 to 1999

See also

- Creatable World

- Lammily – a crowd funded alternative developed by Nickolay Lamm

- List of Barbie animated films

- List of Barbie video games

- Sindy

- Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story

- The Most Popular Girls in School

- Totally Hair Barbie

Notes

References

- ^ a b Ziobro, Paul (January 28, 2016). "Mattel to Add Curvy, Petite, Tall Barbies: Sales of the doll have fallen at double-digit rate for past eight quarters". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ Norton, Kevin I.; Olds, Timothy S.; Olive, Scott; Dank, Stephen (February 1, 1996). "Ken and Barbie at life size". Sex Roles. 34 (3): 287–294. doi:10.1007/BF01544300. ISSN 1573-2762. S2CID 143568530.

- ^ Don Richard Cox, "Barbie and her playmates." Journal of Popular Culture 11.2 (1977): 303-307.

- ^ Mary G. Lord, Forever Barbie: The unauthorized biography of a real doll (Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2004).

- ^ Javaid, Maham (May 25, 2023). "Barbie's 'pornographic' origin story, as told by historians - A new trailer for the Barbie movie shows her visiting the real world. In reality, the doll was based on a German sex toy called Lilli". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ a b "Sassy with a sidelong glance: Meet Lilli, Barbie's German inspiration". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ "Meet Lilli, the High-end German Call Girl Who Became America's Iconic Barbie Doll". Messy Nessy. January 29, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ^ "Ruth Mosko Handler unveils Barbie Doll". Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ^ "Barbie". FirstVersions.com. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "Mattel, Inc. History". International Directory of Company Histories. Vol.61. St. James Press (2000). Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ Dean, Grace. "Barbie is the star of the summer's hottest blockbuster. The much-hyped movie is the pinnacle of a 60-year history filled with rejections, lawsuits, and controversies for the world's most iconic doll". Business Insider. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Jerry (2009). Toy monster: the big, bad world of Mattel. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0071402118.

- ^ "Mattel Wins Ruling in Barbie Dispute". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ "Vintage Barbie struts her stuff". BBC News. September 22, 2006. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "2023 "Barbie Doll Market" Regional Sales and Future Trends Analysis". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "The Long, Complicated, and Very Pink History of Barbiecore". Time. June 27, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "Barbie Animated Film Series". IMDb. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ "Barbie shows signs of life as Mattel plots comeback". Detroit Free Press. April 18, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ a b "Barbie in pop culture". Barbie Media. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ Laurie, Virginia (January 22, 2022). "The Legacy of the Barbie Cinematic Universe". Study Breaks. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Barbie® Makes Music in Mattel Television's New Animated Movie". Mattel Television (Press release). Mattel. August 1, 2020. Archived from the original on September 7, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ Strecker, Erin (February 26, 2013). "Barbie celebrates 25th DVD release today". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

...they've sold over 110 million Barbie DVDs to date!...

- ^ "Barbie Vlogger". Mattel Television (Animation). Mattel. June 19, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ Scott, Ellen (May 30, 2017). "Why it's so powerful for Barbie to talk about mental health". Metro. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ Mitchell, Skylar (October 10, 2020). "Barbie confronts racism in viral video and shows how to be a White ally". CNN. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ "Everything to Know About Margot Robbie's Live-Action 'Barbie' Movie". Us Weekly. March 26, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ Donnelly, Matt (April 26, 2022). "Margot Robbie's Barbie Sets 2023 Release Date, Unveils First-Look Photo". Variety. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ^ Lawrence, Cynthia; Bette Lou Maybee (1962). Here's Barbie. Random House. OCLC 15038159.

- ^ "Original Model Barbie Doll". Wisconsin Historical Society. April 23, 2013.

- ^ Biederman, Marcia (September 20, 1999). "Generation Next: A newly youthful Barbie takes Manhattan". New York. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- ^ The Storybook Romance Comes To An End For Barbie And Ken Archived November 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Mattel February 12, 2004

- ^ Madeover Ken hopes to win back Barbie CNN February 10, 2006

- ^ STRANSKY, TANNER (February 14, 2011). "Valentine's Day Surprise! Barbie and Ken are officially back together". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Kavilanz, Parija (February 14, 2011). "Barbie and Ken: Back together on Valentine's Day". CNN.

- ^ "About Barbie: Family and friends". Mattel.

Barbie has three sisters: Skipper, Stacie, Chelsea

- ^ Joseph Lee (June 29, 2004). "Aussie hunk wins Barbie's heart". CNN Money. CNN. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "About Barbie : Fast Facts". Barbie Media. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- ^ "Musée des Arts Décoratifs". Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

- ^ Neuendorf, Henri (December 3, 2015). "Limited Edition Andy Warhol Barbie Hits the Shelves". Artnet.

- ^ Moore, Hannah (October 2015). "Why Warhol painted Barbie". BBC News.

- ^ Gómez, Edward (May 10, 2014). "Al Carbee's Art of Dolls and Yearning: "Oh, for a real, live Barbie!"". Hyperallergic.

- ^ Bender, Silke (March 12, 2016). "Widerlegt! Die 10 größten Irrtümer über Barbie". Die Welt (in German). Welt.

- ^ "First Barbie-themed restaurant opens in Taiwan". Daily Times. January 31, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Economist 21 Dec 2002, Vol. 365 Issue 8304, pp 20-22.

- ^ "Barbie® Launches New Music Producer Doll to Highlight the Gender Gap in The Industry". Mattel News. September 13, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ "Barbie". Girls Make Beats. September 7, 2021. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ "Barbie Makes Big Announce With Girls Make Beats Introducing New Doll". Stichiz on iHeartRadio. September 14, 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ^ "New Theme Park with A Barbie Beach House is Opening in Arizona in 2024". www.instagram.com. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ "Mattel Adventure Park". www.matteladventurepark.com. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ a b "Barbie and more at Mattel Adventure Park: What to know about the new Arizona theme park". USA TODAY. Retrieved July 25, 2023.

- ^ "Barbie Runway Show – Fall 2009 Mercedes Benz Fashion Week New York". MyItThings.com. February 14, 2009. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Runway Rundown: The Barbie Show's 50 Designers!". TypePad. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Christian Louboutin explains Barbie "fat ankle" comments". Handbag.com. October 16, 2009. Archived from the original on March 3, 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Haneline, Amy. "A girl with a gavel! Barbie debuts judge dolls, partners with GoFundMe to close 'dream gap'". USA Today. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Mattel Unveils #ThankYouHeroes Program from Barbie® Supporting First Responders Children's Foundation". Business Wire. May 13, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ "Barbie Dreamhouse™ Celebrates 60 Years of Giving Dreams a Home™ with Habitat for Humanity Collaboration". Business Wire. February 3, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ Flickr, vaniljapulla // (September 5, 2020). "1992: Barbie tells girls math is hard". The Daily Progress. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ Shapiro, Susan (March 9, 2019). "Barbie, Like her Creator, Is a Feminist". The Daily Beast. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ "Company News: Mattel Says It Erred; Teen Talk Barbie Turns Silent on Math". The New York Times. October 21, 1992. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ^ "Pregnant doll pulled from Wal-Mart after customers complain". USA Today. December 24, 2002.

- ^ ""Jewish" Barbie Dolls Denounced in Saudi Arabia". Adl.org. Archived from the original on May 25, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Barbie at 60, and how she made her mark on the Arab world". Arab News. January 5, 2019. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

- ^ "Al-Ahram Weekly | Living | Move over, Barbie". Weekly.ahram.org.eg. June 7, 2006. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Muslim dolls tackle 'wanton' Barbie". BBC News. March 5, 2002. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Ribon, Pamela (November 18, 2014). "Barbie F*cks It Up Again". Gizmodo. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ Romano, Aja. "Barbie book about programming tells girls they need boys to code for them". Daily Dot. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ a b Buhr, Sarah (November 20, 2014). "Mattel Pulls Sexist Barbie Book "I Can Be A Computer Engineer" Off Amazon". TechCrunch. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ "After Backlash, Computer Engineer Barbie Gets New Set Of Skills". NPR. November 12, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ "2001 Oreo Barbie". October 12, 2007. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ "African American Fashion Dolls of the 60s". MasterCollector.com. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Faces of Christie". Kattisdolls.net. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Ducille, Ann (1994). "Dyes and Dolls: Multicultural Barbie and the merchandising of difference". Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. 6: 46.

- ^ "Mattel introduces black Barbies, to mixed reviews". Fox News. October 9, 2009. Archived from the original on October 11, 2009. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- ^ "A Barbie for Everyone" Hispanic (February–March 2009), Vol. 22, Issue 1

- ^ Perez, Emilie Rose Aguilo (2021). "Commodifying Culture: Mattel's and Disney's Marketing Approaches to "Latinx" Toys and Media". The Marketing of Children's Toys. pp. 143–163. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-62881-9_8. ISBN 978-3-030-62880-2. S2CID 234253829.

- ^ Marco Tosa, Barbie: Four decades of fashion, fantasy, and fun (1998).

- ^ Shan, Li (January 2016). "Barbie breaks the mold with ethnically diverse dolls". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Gilblom, Kelly (February 24, 2021). "How a Barbie Makeover Led to a Pandemic Sales Boom". Bloomberg News. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- ^ "Oreo Fun Barbie". Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2010.

- ^ "Barbie's Disabled Friend Can't Fit". EL SEGUNDO, Calif.: University of Washington. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 1, 2010. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- ^ a b Bancroft, Holly (July 23, 2024). "First blind Barbie released by toy maker Mattel". The Independent. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Barbie | Role Models | Inspiring Women | You Can Be Anything". Barbie.com by Mattel. 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ^ Leguizamon, Mercedes; Ahmed, Saeed (March 7, 2018). "Barbie unveils dolls based on Amelia Earhart, Frida Kahlo, Katherine Johnson and Chloe Kim". CNN News. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ^ "Barbie Has Created A Doll Of Madison De Rozario And It Is So Dang Powerful". Women's Health. Archived from the original on March 15, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ Toma Istomina (March 5, 2020). "Barbie launches doll inspired by Ukrainian fencer Olga Kharlan". Kyiv Post.

- ^ "Fencing focus: Olga Kharlan". FIE official website. June 30, 2020.

- ^ "Barbie Doll Modeled After Naomi Osaka Sells Out Within Hours of Release". Black Enterprise. July 18, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Singer, Melissa (June 15, 2021). "'It sent a message': Julie Bishop just got her own Barbie doll". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Price, Kimberley (August 5, 2021). "Aussie GP honoured as one of six special Barbies". Daily Liberal. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ "Samantha Cristoforetti Barbie Doll". Mattel Creations. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ "Playscale per About.com". About.com. March 2, 2011. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "1959 Blonde Ponytail Barbie Brings Over $3,000!". Scoop. October 16, 2004. Archived from the original on February 23, 2006. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- ^ "Midnight Red Barbie Doll sets auction record". London: Yahoo! Australia. September 27, 2006. Archived from the original on October 3, 2006. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- ^ "Welcome to the official Mattel site for Barbie Collector". BarbieCollector.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Welcome to the official Mattel site for Barbie Collector". BarbieCollector.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Welcome to the official Mattel site for Barbie Collector". BarbieCollector.com. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Collectible Barbie Dolls: Become A Barbie Collector : Barbie Signature". Barbie by Mattel.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008.

- ^ Kelly Murray (September 12, 2020). "Mattel releases second edition of 'Day of the Dead' Barbie". CNN. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Barbie-in-a-blender artist wins $1.8 million award". Out-Law.Com. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "National Barbie-in-a-Blender Day!". Barbieinablender.org. Archived from the original on February 11, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Mattel v. Tom Forsythe" (PDF). June 21, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009. Retrieved August 1, 2016.

- ^ "After Frida Kahlo Barbie Debacle, Licensing Company Sues Artist's Relative". Hyper Allergic. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ "BarbiesShop.com News". Archived from the original on June 11, 2009. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ "Mattel Loses Trade Mark Battle with 'Barbie'". LawdIt UK. July 25, 2005. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Mattel breaks up with Asia Pulp and Paper after Greenpeace's Barbie-based campaign". October 5, 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- ^ "Gangsta Bitch Barbie video". S77.photobucket.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ "Saturday Night Live skit | Inside Barbie's Dream House". S177.photobucket.com. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ Published on Friday November 8, 2002 00:00 (November 8, 2002). "The Scotsman". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Barbie loses battle over bimbo image". BBC News. July 25, 2002. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "Aqua Barbie Girl lyrics". Purelyrics.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "1990's Nissan 300ZX Commercial" YouTube April 25, 2010

- ^ "Nissan Toys 2 Barbie Ken Commercial" youtube April 25, 2010

- ^ "Mattel Sues Nissan Over TV Commercial". The New York Times. September 20, 1997. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ After Aqua, Mattel goes after Car Ad MTV.com September 24, 1997

- ^ Battleground Barbie: When Copyrights Clash Archived October 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Peter Hartlaub, The Los Angeles Daily News, May 31, 1998. Accessed July 3, 2009.

- ^ "Stripper: Barbie Lawsuit a Bust". Wired. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ "Barbie Liberation". Sniggle.net. May 23, 1996. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Firestone, David (December 31, 1993). "While Barbie Talks Tough, G. I. Joe Goes Shopping". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Kuo, Lily (April 20, 2016). "Instagram's White Savior Barbie neatly captures what's wrong with "voluntourism" in Africa". Quartz Africa. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Barbie Savior". Instagram. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ "Bratz topple Barbie from top spot". BBC News. September 9, 2004. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "Barbie blues for toy-maker Mattel". BBC News. October 17, 2005. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "Barbie sues Bratz for $1bn". The Daily Telegraph. London. August 22, 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ^ "Jury rules for Mattel in Bratz doll case". The New York Times. July 18, 2008. Archived from the original on June 23, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ^ "Barbie beats back Bratz". CNN Money. December 4, 2008. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ^ Colker, David (December 4, 2008). "Bad day for the Bratz in L.A. court". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ^ "Court throws out Mattel win over Bratz doll". Reuters. July 22, 2010. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ Mattel Inc. v. MGA Entertainment, Inc. Archived July 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, no. 09-55763 (9th Cir. Jul 22, 2010)

- ^ Chang, Andrea (January 18, 2011). "Mattel, MGA renew fight over Bratz dolls in court". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Federal jury says MGA, not Mattel, owns Bratz copyright". Southern California Public Radio. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

- ^ Chang, Andrea (August 5, 2011). "Mattel must pay MGA $310 million in Bratz case". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- ^ Anderson, Mae (August 3, 2009). "Bratz maker introduces new doll line". Associated Press. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ^ Ziobro, "Mattel to Add Curvy, Petite, Tall Barbies: Sales of the doll have fallen at double-digit rate for past eight quarters". The Wall Street Journal. January 28, 2016.

- ^ Dittmar, Helga; Halliwell, Emma; Ive, Suzanne (2006). "Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5- to 8-year-old girls". Developmental Psychology. 42 (2): 283–292. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.283. ISSN 0012-1649. PMID 16569167.

- ^ Brownell, Kelly D.; Napolitano, Melissa A. (1995). "Distorting reality for children: Body size proportions of Barbie and Ken dolls". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 18 (3): 295–298. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199511)18:3<295::AID-EAT2260180313>3.0.CO;2-R. ISSN 1098-108X. PMID 8556027.

- ^ Dijker, Anton J.M. (March 1, 2008). "Why Barbie feels heavier than Ken: The influence of size-based expectancies and social cues on the illusory perception of weight". Cognition. 106 (3): 1109–1125. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2007.05.009. ISSN 0010-0277. PMID 17599820. S2CID 26233026.

- ^ Anschutz, Doeschka J.; Engels, Rutger C. M. E. (November 1, 2010). "The Effects of Playing with Thin Dolls on Body Image and Food Intake in Young Girls". Sex Roles. 63 (9): 621–630. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9871-6. ISSN 1573-2762. PMC 2991547. PMID 21212808.

- ^ "What would a real life Barbie look like?". BBC News. March 6, 2009. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ a b Eames, Sarah Sink (1990). Barbie Doll Fashion: 1959–1967. Collector Books. ISBN 0-89145-418-7.

- ^ M.G. Lord, Forever Barbie, Chapter 11 ISBN 0-8027-7694-9

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (October 21, 2010). "Barbie (Doll) – Times Topics". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ "Barbie undergoes plastic surgery". BBC News. November 18, 1997. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Winterman, Denise (March 6, 2009). "What would a real life Barbie look like?". BBC News. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Bates, Claire (March 3, 2016). "How does 'Curvy Barbie' compare with an average woman?". BBC News. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Cartner-Morley, Jess (January 28, 2016). "Curvy Barbie: is it the end of the road for the thigh gap?". The Guardian. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Wosk, Julie (February 12, 2016). "The New Curvy Barbie Dolls: What They Tell Us About Being Overweight". Huffington Post. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ a b "Barbie's Got a New Body". Time. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ Ahlgrim, Callie. "A mom found her daughter's 'curvy Barbie' in the trash — and used it to teach her a lesson about body diversity". Business Insider. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ "A woman wondered what Barbies would look like in quarantine. Her answer is amazing". Fast Company. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ Lind, Amy (2008). Battleground: Women, Gender, and Sexuality. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- ^ Rosen, David S.; Adolescence, the Committee on (December 1, 2010). "Identification and Management of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents". Pediatrics. 126 (6): 1240–1253. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-2821. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 21115584.

- ^ "Valeria Lukyanova: Model Seeks to Be Real-Life Barbie Doll". Inquisitr.com. April 23, 2012. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ^ "Valeria Lukyanova & Another Real Life Barbie Doll, Olga Oleynik, Come to America". EnStarz.com. December 10, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ a b "The Barbie Doll Syndrome: Why Girls Are Becoming Obsessed with Unrealistic Curvy Bodies | Women's". Women's. January 13, 2018. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Intern, HL (July 2, 2014). "Mom Of 6 Has 36 Surgeries To Look Like A Barbie Doll — Did It Work?". Hollywood Life. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Dittmar, Helga (2006). "Does Barbie Make Girls Want to Be Thin? The Effect of Experimental Exposure to Images of Dolls on the Body Image of 5- to 8-Year-Old Girls" (PDF). Developmental Psychology. 42 (2): 283–292. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.283. PMID 16569167. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 16, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Radford, Benjamin (2023). "American Beauty:Idolizing Barbie-or Not". Center for Inquiry.

Further reading

- Best, Joel. "Too Much Fun: Toys as Social Problems and the Interpretation of Culture", Symbolic Interaction 21#2 (1998), pp. 197–212. DOI: 10.1525/si.1998.21.2.197 in JSTOR

- BillyBoy* (1987). Barbie: Her Life & Times. Crown. ISBN 978-0-517-59063-8.

- Cox, Don Richard. "Barbie and her playmates." Journal of Popular Culture 11#2 (1977): 303–307.

- Forman-Brunell, Miriam. "Barbie in" LIFE": The Life of Barbie." Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 2#3 (2009): 303-311. online

- Gerber, Robin (2009). Barbie and Ruth: The Story of the World's Most Famous Doll and the Woman Who Created Her. Collins Business. ISBN 978-0-06-134131-1.

- Karniol, Rachel, Tamara Stuemler-Cohen, and Yael Lahav-Gur. "Who Likes Bratz? The Impact of Girls’ Age and Gender Role Orientation on Preferences for Barbie Versus Bratz." Psychology & Marketing 29#11 (2012): 897-906.

- Knaak, Silke, "German Fashion Dolls of the 50&60". Paperback www.barbies.de.

- Lord, M. G. (2004). Forever Barbie: the unauthorized biography of a real doll. New York: Walker & Co. ISBN 978-0-8027-7694-5.

- Plumb, Suzie, ed. (2005). Guys 'n' Dolls: Art, Science, Fashion and Relationships. Royal Pavilion, Art Gallery & Museums. ISBN 0-948723-57-2.

- Rogers, Mary Ann (1999). Barbie culture. London: SAGE Publications. ISBN 0-7619-5888-6.

- Sherman, Aurora M., and Eileen L. Zurbriggen. "'Boys can be anything': Effect of Barbie play on girls’ career cognitions." Sex roles 70.5-6 (2014): 195-208. online

- Singleton, Bridget (2000). The Art of Barbie. London: Vision On. ISBN 0-9537479-2-1.

- Weissman, Kristin Noelle. Barbie: The Icon, the Image, the Ideal: An Analytical Interpretation of the Barbie Doll in Popular Culture (1999).

- Wepman, Dennis. "Handler, Ruth" American National Biography (2000) online

External links

- Official website

- St. Petersburg Times Floridian: "The doll that has everything – almost", an article by Susan Taylor Martin about the "Muslim Barbie"

- USA Today: Barbie at number 43 on the list of The 101 Most Influential People Who Never Lived

- The Telegraph: Doll power: Barbie celebrates 50th anniversary and toy world dominance

- NPR Audio Report: Pretty, Plastic Barbie: Forever What We Make Her

- Lawmaker Wants Barbie Banned in W.Va.; Local Residents Quickly React Archived February 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine March 3, 2009

- New York Times: Barbie: Doll, Icon Or Sexist Symbol? December 23, 1987

- Barbie's 50th Archived November 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine – slideshow by The First Post

- BBC News: Mattel shuts flagship Shanghai Barbie concept store March 7, 2011

- BBC News 1: Making Cindy into Barbie? - BBC News, HEALTH (21 September 1998)

- CBS News: Becoming Barbie: Living Dolls, Real Life Couple Are Models Of Plastic Perfection - by Rebecca Leung (Aug. 6, 2004) CBS News

- Glowka; et al. (2001). "Among the New Words". American Speech. 76 (1). Project MUSE: 79–96. doi:10.1215/00031283-76-1-79.

- Anna Hart, Introducing the new, realistic Barbie: 'The thigh gap has officially gone', The Telegraph website, January 28, 2016