President of Bangladesh

| President of the People's Republic of Bangladesh | |

|---|---|

| গণপ্রজাতন্ত্রী বাংলাদেশের রাষ্ট্রপতি | |

Seal of the president of Bangladesh | |

Standard of the president of Bangladesh | |

since 24 April 2023 | |

| Head of state of the People's Republic of Bangladesh Executive branch of the Government of Bangladesh | |

| Style |

|

| Status | Head of state |

| Residence | Bangabhaban |

| Appointer | All Members of Parliament |

| Term length | Five years, renewable once |

| Precursor | Governor of East Pakistan |

| Inaugural holder | Sheikh Mujibur Rahman |

| Formation | 17 April 1971 |

| Deputy | Vice President of Bangladesh (1971-1972; 1975-1991) |

| Salary | ৳220000 (US$1,800) per month ৳2640000 (US$22,000) annually (incl. allowances) |

| Website | www |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

The president of Bangladesh (Bengali: বাংলাদেশের রাষ্ট্রপতি — Bangladesher Raṣhṭrôpôti), officially the president of the People's Republic of Bangladesh (Bengali: গণপ্রজাতন্ত্রী বাংলাদেশের রাষ্ট্রপতি — Gaṇaprajātantrī Bangladesher Raṣhṭrôpôti), is the head of state of Bangladesh and commander-in-chief of the Bangladesh Armed Forces.

The role of the president has changed three times since Bangladesh achieved independence in 1971. Presidents had been given executive power. In 1991, with the restoration of a democratically elected government, Bangladesh adopted a parliamentary democracy based on a Westminster system. The President is now a largely ceremonial post elected by the Parliament.[1]

In 1996, Parliament passed new laws enhancing the president's executive authority, as laid down in the constitution, after the Parliament is dissolved. The president resides at the Bangabhaban, which is his office and residence. The president is elected by the 350 parliamentarians in an open ballot, and thus generally represents the majority party of the legislature.[2][3][4] He continues to hold office after his five-year term expires until a successor is elected to the presidency.[2]

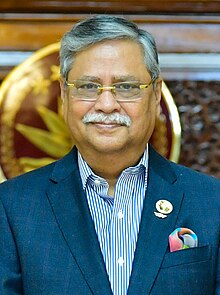

Mohammed Shahabuddin is the current president; he was elected unopposed on 13 February 2023. He took office for a five-year term on Monday, 24 April 2023.

Powers and duties

[edit]Currently, although the position of president holds de jure importance, its de facto powers are largely ceremonial.[1] The Constitution allows the president to act only upon the advice of the prime minister and his/her Cabinet.[2]

Appointments powers

[edit]The president can appoint the following to office:[2]

- By Article 56 (2), the prime minister and his/her Cabinet, with the limitation that the prime minister must be a parliamentarian who holds the confidence of the majority of the House. The president can also dismiss a member of Cabinet upon the request of the prime minister.

- By Article 95, the chief justice and other judges of the court.

- By Article 118, the Bangladesh Election Commission, including the chief.

Prerogative of mercy

[edit]The president has the prerogative of mercy by Article 49 of the Constitution,[2] which allows him to grant a pardon to anybody, overriding any court verdict in Bangladesh.

Legislative powers

[edit]By Article 80, the president can refuse to assent to any bill passed by the parliament, sending it back for review. A bill is enacted only after the president assents to it. But when the bill is passed again by the parliament, if the president further fails or refuse to assent a bill, after a certain period of days, the bill will be automatically transformed into law and will be considered as assented by the president.[citation needed]

Chancellor at universities

[edit]Chancellor is a titular position at universities in Bangladesh, always held by the incumbent president of Bangladesh under the Private Universities Act 1992.[5] The position in public universities is not fixed for the president under any acts or laws (since the erection of a state university in Bangladesh requires an act to be passed in itself),[6] but it has been the custom so far to name the incumbent president of the country as chancellor of all state universities thus established.

Selection process

[edit]Eligibility

[edit]The Constitution of Bangladesh sets the principal qualifications one must meet to be eligible to the office of the president.[7] A person shall not be qualified for election as president if he-

- is less than thirty-five years of age; or

- is not qualified for election a member of Parliament; or

- has been removed from the office of president by impeachment under the Constitution.

Conditions for presidency

[edit]Certain conditions, as per Article 27 of the Constitution, debar any eligible citizen from contesting the presidential elections. The conditions are:

- No person shall hold office as president for more than two terms, whether or not the terms are consecutive.

- The president shall not be a member of Parliament, and if a member of Parliament is elected as president, he shall vacate his seat in Parliament on the day on which he enters upon his office as president.[8]

Election process

[edit]Whenever the office becomes vacant, the new president is chosen by members of Parliament. Although presidential elections involve actual voting by MPs, they tend to vote for the candidate supported by their respective parties. The president may be impeached and subsequently removed from office by a two-thirds majority vote of the parliament.

Oath or affirmation

[edit]The president is required to make and subscribe in the presence of the Speaker of the Jatiya Sangsad, an oath or affirmation that he/she shall protect, preserve and defend the Constitution as follows:[9]

I, (name), do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully discharge the duties of the office of President of Bangladesh according to law:

That I will bear true faith and allegiance to Bangladesh:

That I will preserve, protect and defend the Constitution:

And that I will do right to all manner of people according to law, without fear or favour, affection or ill-will"

— Article 148, Constitution of Bangladesh

Immunity

[edit]The president is granted immunity for all his actions by Article 51 of the Constitution[2] and is not answerable to anybody for his actions, and no criminal charges can be brought to the Court against him. The only exception to this immunity is if the Parliament seeks to impeach the President.

Succession

[edit]Article 54 of the Constitution of Bangladesh provides for the succession of the president. It states that in case of absence due to illness or other reasons, the Speaker of the Jatiya Sangsad will act as the president of Bangladesh until the president resumes office.[2] This Article was used during the ascension of Speaker Jamiruddin Sircar as the acting president of the State following the resignation of former president A. Q. M. Badruddoza Chowdhury,[10] and when President Zillur Rahman could not discharge his duties due to his illness, and later, death.[11]

Since Bangladesh is a parliamentary system, it does not have a vice-president. However, during the presidential system of governance, Bangladesh had a vice-president who would assume the president's role in his absence; the post was abolished by the twelfth amendment to the Constitution in 1991.[12]

Removal

[edit]A president can resign from office by writing a letter by hand to the Speaker. The president can also be impeached by the Parliament. In case of impeachment, the Parliament must bring specific charges against the president, and investigate it themselves, or refer it to any other body for investigation. The president will have the right to defend himself. Following the proceedings, the president is impeached immediately if two-thirds of the Parliament votes in favour, and the Speaker ascends to power.[2]

Presidential residences and office

[edit]The principal Presidential residence at Bangabhaban is located in Dhaka. There is also a Presidential Palace at Uttara Ganabhaban in Natore District.

- Presidential amenities

-

Bangabhaban, official residence of the president, located at Dhaka.

-

Uttara Ganabhaban, the official retreat of the president located in North Bengal.

-

President Guard Regiment, responsible for the security of the president.

-

Special Security Force, provide physical security to the president and prime minister.

-

Biman Bangladesh Airlines Boeing 777-300ER, main presidential aircraft used by the president.

History of the office

[edit]Independence war and parliamentary republic (1971–75)

[edit]At the beginning of the Bangladesh war of independence in April 1971, the Bangladesh Forces, better known as the Mukti Bahini, and the Provisional Government of Bangladesh, popularly called the Mujibnagar Government, were both established. After the oath ceremony held at Meherpur, Kushtia following Yahya Khan's anti-secessionist military operation in Dhaka, the latter government-in-exile (GiE) set up its headquarters at 8 Theatre Road, in Kolkata, India.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (Awami League)

[edit]The de jure president of the GiE and thus the first president of Bangladesh was Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who was the most popular leader of the independence struggle imprisoned shortly after the independence declaration, with vice-president and acting president being Syed Nazrul Islam and Tajuddin Ahmad as prime minister. As the Constituent Assembly of Bangladesh, which was formed out of the East Pakistani elected members of the 1970 Pakistani general election, convened a month after the war on 12 January 1972, he introduced parliamentarism through a presidential decree and left office for the role of prime minister.[13] In December on the first anniversary of the end of the war, the new constitution of the country took effect founding a unitary parliamentary republic based on the British Westminster System and transferring all executive powers to the prime minister.

Later, after the general election in 1973 where Mujib's party the Awami League achieved an expected landslide victory overkilling the opposition (not only because of intimidation of candidates and ballot stuffing by the ruling party leaders),[14] in January 1974, the first presidential election was held. Mohammad Mohammadullah, who replaced Mujib's successor Abu Sayeed Chowdhury as acting president upon the latter's resignation, was indirectly elected uncontested and sworn in as the ceremonial head of state.

Mujib is widely considered the founder of Bangladesh and deemed as the "Father of the Nation" of the country.[15] He is popularly referred with the honorary title of Bangabandhu (বঙ্গবন্ধু "Friend of Bengal"). He introduced the state policy of Bangladesh according to four basic principles: nationalism, secularism, democracy and socialism.[16] He nationalized hundreds of industries and companies as well as abandoned land and capital and initiated land reform aimed at helping millions of poor farmers. Major efforts were launched to rehabilitate an estimated 10 million refugees. He further outlined state programs to expand primary education, sanitation, food, healthcare, water and electric supply across the country. A five-year plan released in 1973 focused state investments into agriculture, rural infrastructure and cottage industries.

After Bangladesh achieved recognition from most countries, Mujib helped Bangladesh enter into the United Nations and the Non-Aligned Movement. He travelled to the United States, the United Kingdom and other European nations to obtain humanitarian and developmental assistance for the nation. He signed a treaty of friendship with India, which pledged extensive economic and humanitarian assistance and began training Bangladesh's security forces and government personnel.

Mujib's premiership however faced serious challenges, which included the rehabilitation of millions of people displaced in 1971, organizing the supply of food, health aids and other necessities. The effects of the 1970 cyclone had not worn off, and the state's economy had immensely deteriorated by the conflict. Economically, Mujib's huge nationalization program and socialist planning caused the economy to suffer. By the end of the year, thousands of Bengalis arrived from Pakistan, and thousands of non-Bengalis migrated to Pakistan; and yet many thousands remained in refugee camps. Mujib forged a close friendship with Indira Gandhi, strongly praising India's decision to intercede, and professed admiration and friendship for India. In the aftermath of the 1974 Famine, there was growing dissatisfaction with his government.

Presidential system and autocratic one-party state (1975)

[edit]Irked by the heavy criticism from the opposition and news outlets and worried about the Awami League's prospects in the next election, on 28 December 1974 Mujib declared a state of emergency.[17] The following month, he openly advocated to the view that parliamentarism has failed in the country and had the lawmakers amend the constitution to revive the presidential system in order to better manage emergencies in the country. After assuming the presidency again, Mujib criticized "free-style" liberal democracy and established an autocratic one-party state with the strongly socialist Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League as the national party and him as the unelected president and unopposed supreme leader for life. He banned all other political parties and activities while sharply curtailing freedom of speech and the press.[18][19]

However, these changes were remarked as the "Second Revolution" by Mujib.[20] In bringing together all politicians under a single national party apparently for the sake of unity of the country during a critical period it struck a similarity to Abraham Lincoln's National Union Party during the height of the American Civil War. The new party obliged all members of parliament, government and semi-autonomous associations and bodies to join,[20] as well as intimidated and violently punished or eliminated opposition to the regime using the Jatiya Rakkhi Bahini, the paramilitary "national defence force" and the ruling party's armed wing.[21]

Military juntas and democratic presidencies (1975–1991)

[edit]Soon after, some close associates of Mujibur Rahman, who were ministers and secretaries, joined an assassination plot by the Bangladesh Army. On 15 August 1975, Mujib was assassinated in a coup d'état by some mid-ranking army officers,[22][23] and replaced by one of his long time associates and cabinet members who was in a bitter bureaucratic rivalry with his loyalists, Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad.[24] Immediately after, martial law was promulgated in the country.

As soon as he assumed presidency, along with replacing the national slogan of Joy Bangla ("Hail Bengal"), a cry of Bengali nationalism with Bangladesh Zindabad ("Love Live Bangladesh") calling for Bangladeshi nationalism instead, Mostaq replaced all three armed forces chiefs with next in line seniors to likely ensure the lack of Mujib loyalists in the military.[25] He also proclaimed the Indemnity Ordinance, which granted immunity from prosecution to the assassins of Mujib.[26] Yet only a few months later on 3 November, his regime faced a bloodless coup by pro-Mujib officers led by Brigadier General Khaled Mosharraf in an attempt to depose Mostaq and the military assassins backing his government.[27] At night, presumably on Mostaq's orders, some army officers secretly carried out the killing of the imprisoned Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmed, Abul Hasnat Muhammad Qamaruzzaman and Mujib's new PM Muhammad Mansur Ali.[28][29] With the ousting of Mostaq three days later and the constitutional requirement for the direct election of the president and role of the vice-president as acting president suspended by Mostaq,[30] Chief Justice Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem was appointed to the presidency of what became a military interim government.[31] However, the next day a popular uprising led by the retired lieutenant colonel Abu Taher ended in yet another coup with the deaths of several military generals, including Mosharraf.[32] With Mosharraf dead, the office of Chief Martial Law Administrator (CMLA) was taken by Sayem. Sayem dissolved the parliament and scheduled a general election in February 1977 in a presidential speech addressed to the nation but indefinitely postponed it in November 1976.[33] Mostaq Ahmad was sentenced for five years for corruption and abuse of power.[33]

Ziaur Rahman (Bangladesh Nationalist Party)

Major General Ziaur Rahman, a renowned war hero who was put under house arrest on alleged charges of participation in the Mujib assassination plot (probably due to being among Mostaq's promoted armed forces chiefs),[25] emerged into the political scene when restored to the post of Chief of Army Staff following the uprising. With the country in a dire situation and no stability and security, he was promoted from one of Sayem's deputies to CMLA in November 1976.[33][16]

With Zia's military loyalists now running the state from behind, initially as Deputy CMLA (DCMLA) he sought to invigorate government policy and administration. Hence on 21 April 1977,[34] when Sayem retired on health grounds,[35] without a vice-president Zia assumed acting presidency. The presidency was legitimized 40 days later through a national confidence referendum. Finally in the presidential election the following year, Zia became the first directly elected president. His government removed the remaining restrictions on political parties and encouraged all opposition parties to participate in the pending general election while putting military generals into politics. More than 30 parties vied in the 1979 general election, and with massive public support, Zia's Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) achieved a single-party majority.[36] After the election in February, the withdrawal of martial law was proclaimed on 6 April and the 2nd parliament was formed 9 days later.[37]

Drifting away from the Secular State and Liberal Nationalism

Zia moved to lead the nation in a new direction, significantly different from the ideology and agenda of the 1st parliament of Bangladesh.[38] He issued a proclamation order amending the constitution, replacing secularism with increasing the faith of the people in their creator, following the same tactics that was used in Pakistan during the Ayub Khan regime to establish a military rule over civilian democratic rule in the government system. In the preamble, he inserted the salutation "Bismillahir-Rahmaanir-Rahim" (In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful). In Article 8(1) and 8(1A) the statement "absolute trust and faith in Almighty Allah" was added, replacing the commitment to secularism. Socialism was redefined as "economic and social justice."[39] In Article 25(2), Zia introduced the principle that "the state shall endeavour to consolidate, preserve and strengthen fraternal relations among Muslim countries based on Islamic solidarity."[40] Zia's edits to the constitution redefined the nature of the republic from the secularism laid out by Sheikh Mujib and his supporters.[39] Islamic religious education was introduced as a compulsory subject in Bangladeshi schools, with provisions for non-Muslim students to learn of their own religions.[41]

In public speeches and policies that he formulated, Zia began expounding "Bangladeshi nationalism," as opposed to Mujib's assertion of a Liberal Nationalism that emphasised on the liberation of Bengalis from Pakistan's autocratic regime. Zia emphasised the national role of Islam (as practised by the majority of Bangladeshis). Claiming to promote an inclusive national identity, Zia reached out to non-Bengali minorities such as the Santals, Garos, Manipuris and Chakmas, as well as the Urdu-speaking peoples of Bihari origin. However, many of these groups were predominantly Hindu and Buddhist and were alienated by Zia's promotion of political Islam. In an effort to promote cultural assimilation and economic development, Zia appointed a Chittagong Hill Tracts Development Commission in 1976, but resisted holding a political dialogue with the representatives of the hill tribes on the issue of autonomy and cultural self-preservation.[42] On 2 July 1977 Ziaur Rahman organised a tribal convention to promote a dialogue between the government and tribal groups. However, most cultural and political issues would remain unresolved and intermittent incidents of inter-community violence and militancy occurred throughout Zia's rule.[42]

Reforms and international relations

Notable mentions of Ziaur Rahman's tenure as a president have been radical reforms both in country's infrastructure and diplomacy. President Zia successfully pointed out the grounds those could be effectively and exclusively decisive for development of Bangladesh and his reforms covered the political, economical, agricultural and military infrastructure of Bangladesh. Reorganisation of Bangladesh's international relations are especially mentionable because it had active influence over both economy and politics. He successfully bailed Bangladesh out of the Indo-Soviet bloc and grabbed the distancing strings to put bar on the gradually deterioration of Bangladeshi relations with the Western world. Zia gave attention to the other Eastern superpower China that later helped Bangladesh hugely to recover from economical setbacks and to enrich the arsenal of her armed forces.[citation needed]

The most notable of Zia's reformed diplomacy was establishing a relationship with the Muslim world as well as the Middle East. The present bulk overseas recruitment of Bangladeshi migrant workers to Middle Eastern countries are direct outcome of Zia's efforts those he put to develop a long-lasting relationship with the Muslim leadership of the world. The purpose of Middle East relations has been largely economical whereas the rapid improvement of relations with China was particularly made to for rapid advancement of the country's armed forces.[citation needed]

Throughout the study of Zia's international relations it could have been suggested that attention to the bigger neighbour India has been largely ignored. But Zia was found to put strong emphasis on regional co-operation particularly for South Asia. It came evident after Zia took initiative to found SAARC. Zia's dream of Bangladesh's involvement in a strong regional co-operation was met after 4 years of his assassination when SAARC got founded on 8 December 1985 with a key role of the then Bangladeshi authority.[citation needed]

Assassination of Ziaur Rahman

In 1981, Zia was assassinated by fractions of the military who were dissatisfied with his non-conventional means of running many state affairs including the military. Vice-President Justice Abdus Sattar was constitutionally sworn in as acting president. He declared a new national emergency and called for elections within 6 months. Sattar was elected president and won. Sattar was ineffective, however, and Army Chief of Staff, Lt. Gen. H.M. Ershad assumed power in a bloodless coup in March 1982.[citation needed]

Hussain Muhammad Ershad (Jatiya Party)

Like his predecessors, Ershad dissolved parliament, declared martial law, assumed the position of CMLA, suspended the constitution, and banned political activity. Ershad reaffirmed Bangladesh's moderate, non-aligned foreign policy.[16]

In December 1983, he assumed the presidency. Over the ensuing months, Ershad sought a formula for elections while dealing with potential threats to public order.[16]

On 1 January 1986, full political rights, including the right to hold large public rallies, were restored. At the same time, the Jatiyo (People's) Party (JP), designed as Ershad's political vehicle for the transition from martial law, was established. Ershad resigned as chief of army staff, retired from military service, and was elected president in October 1986. (Both the BNP and the AL refused to put up an opposing candidate.)[16]

In July 1987, the opposition parties united for the first time in opposition to government policies. Ershad declared a state of emergency in November, dissolved parliament in December, and scheduled new parliamentary elections for March 1988.

All major opposition parties refused to participate. Ershad's party won 251 of the 300 seats; three other political parties which did participate, as well as a number of independent candidates, shared the remaining seats. This parliament passed a large number of legislative bills, including a controversial amendment making Islam the state religion.

By mid-1990, opposition to Ershad's rule had escalated. November and December 1990 were marked by general strikes, increased campus protests, public rallies, and a general disintegration of law and order. Ershad resigned in December 1990. Following his resignation an interim government was formed with Chief Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed as acting president. He conducted a general election in February 1991, in which the BNP led by Ziaur Rahman's widow Khaleda Zia won the largest number of seats though 11 short of a majority, and a constitutional referendum in September, which put into effect the constitutional amendment to restore the parliamentary system and transfer all executive power from the president back to the prime minister.

Restoration of Parliamentary system (1991—present)

[edit]It was reverted to democratic parliamentary system in 1991 when Khaleda Zia became the first female prime minister of Bangladesh through parliamentary election.

The president is the head of state, a largely ceremonial post elected by the parliament.[1] However, the president's powers have been substantially expanded during the tenure of a caretaker government, which is responsible for the conduct of elections and transfer of power. The officers of the caretaker government must be non-partisan and are given three months to complete their task. This transitional arrangement is an innovation that was pioneered by Bangladesh in its 1991 election and then institutionalised in 1996 through its 13th constitutional amendment.[12]

In the caretaker government, the president has the power to control over the Ministry of Defence, the authority to declare a state of emergency, and the power to dismiss the Chief Adviser and other members of the caretaker government. Once elections have been held and a new government and Parliament are in place, the president's powers and position revert to their largely ceremonial role. The Chief Adviser and other advisers to the caretaker government must be appointed within 15 days after the current Parliament expires.[43]

See also

[edit]- List of presidents of Bangladesh

- Prime Minister of Bangladesh

- Vice President of Bangladesh

- Deputy Prime Minister of Bangladesh

- Politics of Bangladesh

- Caretaker government

- Foreign Minister of Bangladesh

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Background Note: Bangladesh", US Department of State, May 2007

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Presidential Election Act, 1991". CommonLII. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Chowdhury, M. Jashim Ali (6 November 2010). "Reminiscence of a lost battle: Arguing for the revival of second schedule". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "The Private University Act, 1992". Südasien-Institut. Archived from the original on 25 April 2003. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "Ministry of Education – Law/Act". Ministry of Education, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 23 April 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "Chapter I-The President". Prime Minister's Office of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.

- ^ "The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh: 50. Term of office of President".

- ^ Third Schedule After the 12th Amendment (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2017, retrieved 26 April 2018

- ^ "Barrister Md. Jamiruddin Sircar". Bangabhaban. Archived from the original on 3 January 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Speaker acting as President". bdnews24.com. 14 March 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ a b Ahamed, Emajuddin (2012). "Constitutional Amendments". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Mujib Administration's Policy Action Timeline". 16 March 2020.

- ^ Noorana, Mosammat (2015). "Patterns of Electoral Violence in Bangladesh: A Study on Parliamentary Elections (1973-2008)" (PDF). Jagannath University Journal of Social Sciences. 3 (1–2): 128.

- ^ "Immortal Bangabandhu | Daily Sun |". August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Bangladesh History: An overview". Virtual Bangladesh. Virtual Bangladesh. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- ^ "State of emergency announced in Dacca". The Tuscaloosa News. Associated Press. 29 December 1974. p. 6A. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ "Mujib names his Govt". The Sydney Morning Herald. Australian Associated Press-Reuter. 28 January 1975. p. 4. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Ahmad, Ahrar (4 November 2022). "Constitutional supremacy: The dangers within". The Daily Star.

- ^ a b "Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League". Banglapedia. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ Ahamed, Emajuddin (2004). "The military and democracy in Bangladesh" (PDF). In May, Ronald James; Selochan, Viberto (eds.). The Military and Democracy in Asia and the Pacific. Sydney: Australian National University Press. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-1-920942-01-4.

- ^ "Bangladesh Coup: A Day of Killings". The New York Times. 23 August 1975.

- ^ "Mu jib Reported Overthrown and Killed in a Coup by the Bangladesh Military". The New York Times. 15 August 1975.

- ^ "Muhammad Ali in Bangladesh: 35 Years Ago The Champ Visited A New Nation In Turmoil". International Business Times. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b "When Caesar died . . . and with him all the tribunes". The Daily Star. 19 November 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ Khan, Saleh Athar (2012). "Ahmad, Khondakar Mostaq". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Borders, William (6 November 1975). "President of Bangladesh Resigns, Nearly 3 Months After Coup, in Confrontation With Military Officers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 August 2020 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Dasgupta, Sukharanjan (1978). Midnight Massacre in Dacca. New Delhi: Vikas. pp. 77–78. ISBN 0-7069-0692-6.

Khondakar also knew that the situation was bound to be grave once Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmed, Kamaruzzaman and Mansur Ali were released ... Khondakar had them arrested under various pretexts shortly after Mujib's assassination, who remained in Dacca Jail. Khondakar ordered the assassination of the jailed four leaders.

- ^ Newton, Michael (2014). Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-61069-286-1.

- ^ Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Proclamation". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir, eds. (2012). "Rahman, Shahid Ziaur". Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 20 November 2024.

- ^ Lifschultz, Lawrence (1979). Bangladesh: The Unfinished Revolution. United Kingdom: Zed Books. ISBN 9780905762074.

- ^ a b c Preston, Ian (2005) [First published 2001]. A Political Chronology of Central, South and East Asia. Europa Publications. p. 17. ISBN 9781857431148.

- ^ Hoque, Kazi Ebadul (22 March 2015). "Sayem, Justice Abusadat Mohammad". Banglapedia. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ "April 22, 1977, Forty Years Ago". The Indian Express. 22 April 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ Bangladesh 1979 Inter-Parliamentary Union

- ^ MARTIAL LAW IN BANGLADESH, 1975-1979: A Legal Analysis

- ^ Country Studies, Bangladesh (12 September 2006). Zia regime. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- ^ a b Charles Kennedy; Craig Baxter, eds. (11 July 2006). Governance and Politics in South Asia. Avalon. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-8133-3901-6.

- ^ Ahamed, Emajuddin (2012). "Rahman, Shahid Ziaur". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015.

- ^ Raman, B. (29 August 2006). "Zia and Islam". Archived from the original (PHP) on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2006.

- ^ a b Majumder, Shantanu (2012). "Parbatya Chattagram Jana-Samhati Samiti". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 20 January 2016.

- ^ "World Atlas – About Bangladesh". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2011. Bangladesh Government Information