Bajío

Mexican Lowlands

El Bajío | |

|---|---|

Region | |

Templo Expiatorio (León), panoramic of Querétaro City, panoramic of Guanajuato, Aguascalientes capitol, Colonial town of Lagos de Moreno, Public library of the College of St. Nicholas (Morelia), panoramic of Guadalajara, downtown Zacatecas | |

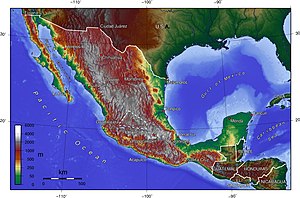

El Bajío outlined in red | |

| |

| Coordinates: 20°28′24″N 101°12′02″W / 20.473335°N 101.200562°W | |

| Country | Mexico |

| States | Guanajuato, Aguascalientes, parts of Querétaro, Jalisco, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí, Michoacan |

The Bajío (the lowland) is a cultural and geographical region within the central Mexican plateau which roughly spans from northwest of Mexico City to the main silver mines in the northern-central part of the country. This includes (from south to north) the states of Querétaro, Guanajuato, parts of Jalisco (Centro, Los Altos de Jalisco), Aguascalientes and parts of Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí and Michoacán.

Located at the border between Mesoamerica and Aridoamerica, El Bajío saw relatively few permanent settlements and big civilizations during Pre-Columbian history, being mostly inhabited by nomadic tribes known to the Aztecs as "The Chichimeca" peoples, another Nahua group from whom the Toltec and the Aztecs were probably descended. The tribes that inhabited El Bajío proved to be some of the hardest to conquer for the Spanish—peace was ultimately achieved via truce and negotiation—but due to its strategic location in the Silver Route, it also drew prominent attention from the Spanish crown and some of the flagship Mexican colonial cities were built there, such as Guanajuato and Zacatecas. Abundant mineral wealth and favorable farming conditions would soon turn the region into one of New Spain's wealthiest. At the beginning of the 19th century, El Bajío was also the place of the ignition of the Mexican War of Independence, and saw most of its battles during the initial phase of the war, including the Cry of Dolores, the storming of the Alhóndiga de Granaditas and the Battle of Calderón Bridge.

Nowadays, the region features one of the strongest economies in Mexico and Latin America, drawing both domestic investment from the adjacent, industry-heavy State of Mexico, as well as foreign companies seeking cheap specialized labor and decent infrastructure[1] (mostly American, Japanese and to some extent, European vehicle and electronics companies).[2][3][4][5] The largest cities of the Bajío are Guadalajara, León, Santiago de Querétaro, and Aguascalientes.[6]

History

[edit]

The Bajío rose to world prominence during the three centuries of colonial rule, providing much of the mineral and agricultural wealth of the Spanish Empire.[7] As such, it was also the birthplace of the Mexican War of Independence, during which criollo elites long established in the Bajío gathered the masses to revolt against Napoleonic rule in Spain, seen as a threat to the established order in America. That said, previous historical landmarks may be traced back to Pre-Columbian times.

Pre-Columbian

[edit]

Recent archeological studies have discovered an extensive historic cultural tradition that is unique to the region, particularly along the flood plains of the Lerma and the Laja Rivers. The Bajío Culture flourished from 300 to 650 CE, with cultural centers ranging from El Cóporo in the far north of Guanajuato to Plazuelas in the far southwest.[8] More than 1,400 sites have been discovered throughout the state of Guanajuato, with only the sites of Cañada de la Virgen, El Cóporo, Peralta, and Plazuelas having received extensive study.

The Bajio from pre-Columbian times is best remembered from the Chichimeca nations, the name given by the Mexicas to a group of indigenous chiefdoms without clear states, boundaries or dwelling places, who inhabited the center and north of the country,[9][7] such as Guachichiles, Guamares, Pames, Tecuexes, among others.[10]

Colonial

[edit]

By 1536 the Spanish and the Otomí leader Conín had founded the multi-ethnic city of Santiago de Querétaro. On the dawn of European expansion with the expedition of Nuño de Guzmán and the Spanish acquisition of the Purepecha Empire after 1530, the region north of the limits of Mesoamerican civilization was also known as the Great Chichimeca, and was the epicenter of the Chichimeca War in the 16th century. The Chichimeca War confronted the Holy Roman Empire and Habsburg Europe at large under Charles V against the native chiefdoms of the Caxcans, the Zacatecs, the Guamares and other nomadic Uto-Nahuan peoples, with the goal of conquering their lands and exploiting silver discovered between 1540 and 1590. The resulting economic activity would quickly become the economic engine of the Kingdom of New Galicia, and the Viceroyalty of New Spain at large, serving as a pivotal hub for world commerce between Europe and Asia (see Global silver trade from the 16th to 19th centuries).[7][11]

Valladolid (today Morelia), Guadalajara, among other cities were often founded with the goal to contain the "barbarian" tribes and protect Spanish families. The discovery of the mines of Zacatecas and Guanajuato, on the other hand, caused a high arrival of Spanish and Tlaxcaltec people to the area, which led to the founding of towns such as San Miguel el Grande (1542), Celaya (1571), Zamora (1574) Aguascalientes (1575) and León (1576), Durango, Chihuahua, Santa Fe Nuevo México: the so-called Silver Route of the Spanish treasure fleet.[10] Meanwhile, king Philip II of Spain orchestrated most of the Counter-Reformation in Europe and the Fourth Ottoman–Venetian War in large part with the wealth provided by settlers, indigenous people and African slaves from the American colonial enterprise centered at the Bajío. For much of the 16th century, the Bajío was characterized by its coming and going of cattle from Querétaro and Lake Chapala, by the ongoing silver rush and by the "warlike spirit" arising from the Chichimeca War, [10]w hich culminated with severe reductions in Chichimeca populations due to war and smallpox. The Chichimecas were reduced to a few settlements in the highlands, or, immersed in the new order.[7]

Throughout the 17th century, cities such as Irapuato, Salamanca and Salvatierra were founded, which, together with the large cities of the Bajío (Guadalajara, Guanajuato, Querétaro, Valladolid or Nueva Michoacán), experienced little population growth. It was not until the 18th century that there was a rise in population throughout New Spain, especially in the Bajío, which came hand in hand with high urban development.[10] However, the greatest boom occurred in the economic sphere.[7] It was the Bajío that provided meat, grains and manufacturing to the mining areas of the West, North Central, North Mexico and, later, to Mexico City itself.[10]

During the Enlightenment, the prosperity of the Bajío was produced through a distinguished institutional format (such as the hacienda, slavery, peonage, etc.),[10] an institutional format also very present in cities and towns in the Bajío in the form of schools, colleges and seminaries (see List of colonial universities in Hispanic America).[10] The College of Saint Nicholas (1540), the University of Guanajuato (1732) and the University of Guadalajara (1792) can be traced back to this era.

Mexican Independence

[edit]

The war that led to the independence of New Spain has roots in its academic life, mainly in the classrooms of the Jesuits and Oratorians of the Bajío.[10] In urban centers since the end of the 18th century, conspiracies were organized, and from 1810 onwards insurgents emerged who supported the independence cause; earning the Bajío the title of cradle of the Mexican Independence.[10] Miguel Hidalgo, Ignacio Allende, the Aldama brothers, Josefa Ortíz de Domínguez, José María Morelos among other figures of the early phase of Mexican Independence were born and lived in the Bajío. On September 13 1810, Epigmenio González was taken prisoner, who had an arsenal of weapons destined for the insurgency. On the 15th, the corregidor of Querétaro, Miguel Domínguez, and his wife, Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez, were arrested. Some historians claim that she managed to send a message to Captain Ignacio Allende and Miguel Hidalgo, through Ignacio Pérez, a member of her militia who rode to San Miguel el Grande (today San Miguel de Allende) to inform those who would start the Mexican War of Independence that the conspiracy had been discovered. The most remembered event occurred in the early morning of September 16, 1810. In a small town called Dolores (today Dolores Hidalgo), father Miguel Hidalgo (born in Pénjamo) and his fellow insurgents rose up in arms against the viceregal regime, launching the famous Cry of Dolores.

19th century

[edit]

In 1847 the city of Querétaro was named the capital of Mexico after Mexico City was invaded by the United States.[12] On May 30, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, forcing Mexico to lose the northern half of its territory in exchange for ending the occupation of Mexico City and the main Mexican ports such as Veracruz.

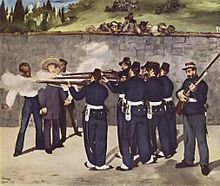

In 1867, two battles were fought between the Republican armies of Benito Juárez and French-Austrian Imperial armies at Cerro de las Campanas, during the Siege of Querétaro. Maximilian of Austria (emperor of Mexico) was captured, tried and sentenced, being shot on June 19 at Cerro de las Campanas, along with the Mexican generals Miguel Miramón and Tomás Mejía.

Mexican Revolution, Cristiada and contemporary Mexico

[edit]

In the Bajío in April 1915, during the Mexican Revolution, General Álvaro Obregón provoked decisive battles against Pancho Villa, whose troops lost in June that year outside the city of Celaya, in the State of Guanajuato.

The Aguascalientes Convention was a meeting that took place during the Mexican Revolution, convened on October 1, 1914 by Venustiano Carranza, first head of the Constitutionalist Army, under the name of "Great Convention of Military Chiefs in Command of Forces and Governors of the States", and whose initial sessions took place in the Chamber of Deputies in Mexico City. Although, later, they were moved to Aguascalientes, after which the convention is named, and was held from October 10 to November 9, 1914. The Zapatistas did not enter the Convention from the beginning.

On February 2 of 1916 the third and current Constitution of Mexico was signed at the Teather of the Republic, in Querétaro. The city was again named provisional capital of the country, this time by President Venustiano Carranza, and for the duration of the Constitutional Convention.[13]

The Cristero War was fought mainly in the Bajío, in areas of the states of Michoacán, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Querétaro and Aguascalientes. The leadership of the movement, close to the Catholic Church, believed that a military solution to the conflict was viable. In January 1927, the stockpiling of weapons began. The first guerrillas were made up of peasants. Support for the armed groups grew. More and more people joined the proclamations of "Long live Christ the King!" and "Long live Saint Mary of Guadalupe!". The origin of the noun Cristero is disputed. There are those who believe that it was the Cristeros themselves who first used the name to identify themselves. But there are researchers of the phenomenon, such as Jean Meyer, who believe that, in its origins, it was a derogatory expression, used by agents of the federal government. The Cristeros were able to quickly articulate a series of local rebellions against the "Sonora Group", a name created after the Sonoran presidents Adolfo de la Huerta, Álvaro Obregón and Plutarco Elías Calles.

Geography

[edit]The Bajío region lies in the basins of the Rio Lerma and Río Grande de Santiago. The valleys of the Lerma-Chapala basin are the result of volcanic activity during the Pliocene geological period and the Quaternary period, which at one time produced large inland lakes due to the obstruction of the outflow of their waters.[14]

With an area over 50 000 km2, and a moderately variable topology, distinct subregions within the Bajío can offer microclimates ranging from the temperate to the humid subtropical or dry steppes. The highest peak in the Bajío is Siete Cruces, in the state of Guanajuato, with an elevation of 3053 m.

In general the region is usually associated with the States of Guanajuato and Querétaro, even though those two states form only a part of the Bajío. It is now characterized by its highly mechanized agriculture, with mean precipitation in the order of 700 millimeters (28 in) per annum (one of the highest in the country). During the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the area was known as the breadbasket of the territory. As of 2014, the region produces sorghum, wheat and maize as its main crops.

-

Agave fields near Cerro de la Mesa (in the background). Lagos de Moreno, Jalisco.

-

Real de Catorce, San Luis Potosí.

-

Fields near Celaya, Guanajuato.

States

[edit]| State | Aguascalientes |

Guanajuato |

Jalisco |

Michoacan |

Querétaro |

| Seal |

|

|

|

|

|

| Capital | Aguascalientes | Guanajuato | Guadalajara | Morelia | Querétaro |

Secondary states sometimes considered as partly contributing to El Bajío or enclosing it: Michoacán, Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí and Estado de México (State of Mexico).

Demography

[edit]Largest cities

[edit]| Rank | City | State | Population (2020) | Metro Area (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Guadalajara | Jalisco | 1,460,148 | 5,268,642 |

| 2 | León | Guanajuato | 1,721,199 | 2,140,354 |

| 3 | Santiago de Querétaro | Querétaro | 1,049,777 | 1,594,212 |

| 4 | Aguascalientes | Aguascalientes | 863,893 | 1,140,916 |

| 5 | Celaya | Guanajuato | 378,143 | 767,104 |

| 6 | Irapuato | Guanajuato | 452,090 | 529,979 |

| 7 | San Juan del Río | Querétaro | 177,719 | 402,112 |

| 8 | Salamanca | Guanajuato | 160,682 | 273,417 |

| 10 | Guanajuato | Guanajuato | 194,500 | 194,500 |

| 9 | Tepatitlán de Morelos | Jalisco | 98,842 | 150,190 |

- Largest cities in the Mexican Bajío.

-

Guadalajara, Jalisco.

-

León, Guanajuato.

-

Irapuato, Guanajuato.

Economy

[edit]

Today, the region is one of the fastest-growing in the country. This has caused the metropolitan areas to attract many migrants from other parts of Mexico.[15][16][17] The region has had an outstanding industrial and economic development in the last 15 years. The cities of El Bajío have one of the highest income per capita figures in Mexico.[18]

Tourism

[edit]Due to its colonial heritage, the Bajío is home to around eight UNESCO World Heritage Sites (depending on how its limits are defined):

- Downtown Querétaro City.

- Franciscan Missions in the Sierra Gorda (shrines in the rural Querétaro Huasteca region, by Junípero Serra, also founder of many Californian missions).

- Guanajuato City and adjacent mines.

- San Miguel de Allende and Sanctuary of Jesús Nazareno de Atotonilco (town in the state of Guanajuato).

- Hospicio Cabañas (colonial hospital complex and art museum in Guadalajara).

- Agave Landscape and Ancient Industrial Facilities of Tequila (Jalisco).

- Zacatecas City

- Camino Real de Tierra Adentro

- Downtown Morelia

Industry

[edit]

El Bajio has long been a hub for the national industrial market, because it naturally sits between Mexico's three main cities: Mexico City to the south, Guadalajara to the west and Monterrey to the northeast.[19] The region has attracted foreign companies due to its relative proximity to the United States, second only in American manufacturing plants to the Mexico-US border. Faster access to port cities such as Manzanillo, Tampico and Veracruz compared to border cities is also attractive for Asian and European markets. The main investor was Japan, although the United States, South Korea, Germany, France, Italy and Spain also have important presence in the area.[19][20] It is estimated that, by 2016, Asian foreign direct investment totaled over 1.5 billion dollars. Guanajuato (León-Silao and Celaya) hosts General Motors, Pirelli, Honda, Toyota, Mazda, Denso, Mitsubishi, and Sumitomo plants. Aguascalientes hosts Nissan, Renault, Mercedes, Yazaki and Jatco plants. Querétaro hosts Mitsubishi, Samsung, Bombardier and Safran plants. San Luis Potosí hosts BMW and Yazaki.[19] The State of Mexico (Cuautitlán Izcalli) hosts a Ford plant.

Bajío Shimbun is a monthly, Japanese-language newspaper founded in June 2015.[21] The first Japanese consulate was inaugurated in January 2016 in León to serve the Bajío region.[22] As of 2017 there were 1143 Japanese, 294 United-Statesians and 200 Spanish legal immigrants in Aguascalientes according to the immigration authorities, although the total number of immigrants is thought to be much higher.[23] In 2015, authorities reported a total of 6230 legally-registered immigrants in the state of Querétaro, most of them from the United States, Spain, Colombia, South Korea, Germany, Cuba, France, Canada, Japan and Venezuela.[24]

Now archetypal in the development plans of the local governments, these business partnerships with multinational corporations have been criticized for exploiting Mexico's weak labor laws and low wages,[25][26] lacking long-term potential of benefiting the local population and for outsourcing jobs out of their countries of origin in the developed world.[27]

Culture

[edit]The Bajío is known for being the cradle of Mexican independence from the Spanish Empire, and for being one of the conservative bastions of Mexican Catholicism.

-

El Cubilete hill, Silao, Guanajuato.

-

San Juan de los Lagos, Jalisco.

-

Pabellón de Hidalgo, Aguascalientes.

-

Sanctuary of Plateros (Sanctuary of Silversmiths), Fresnillo, Zacatecas.

-

Bernal, Querétaro.

-

Guanajuato, Guanajuato.

-

Morelia, Michoacán.

-

Zacatecas, Zacatecas.

-

San Luis Potosí, San Luis Potosí.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Mexican manufacturing - from sweatshops to high-tech motors". Reuters. April 9, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ "The so called great Bajio in Mexico: a case of booming economic regional growth". RSA Main. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Winterfeldt, Liv (April 13, 2022). "The Bajío Region: Engine of the Mexican Economy". WMP Mexico Advisors. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ "As Mexico's Commercial Real Estate Soars, Second Tier Cities Attract First-Rate Attention". Nearshore Americas. June 16, 2014.

- ^ "Entrada Group: at the heart of Mexico's thriving manufacturing industry". European CEO. January 10, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ "The Bajío Guide - Mexico Travel". Rough Guides. Archived from the original on May 9, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Tutino, John (2011). Making a New World: Founding Capitalism in the Bajío and Spanish North America. Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/9780822394013. ISBN 978-0-8223-4974-7.

- ^ Butzer, Karl and Elisabeth Butzer. 1997. "The Natural Vegetation of the Mexican Bajío: Archival Documentation of a Sixteenth Century Savannah Environment." Quaternary International 43, no. 4: 161-72.

- ^ "Historia de México: Los chichimecas". March 6, 2016. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i González y González, Luis (November 6, 2019). "Ciudades y villas del bajío colonial". colmich.repositorioinstitucional.mx. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ Weatherford, Jack McIver (1990). Indian givers: how the Indians of the Americas transformed the world. Ballantine books history (1. Ballantine books ed.). New York, NY: Fawcett Columbine. ISBN 978-0-449-90496-1.

- ^ "Explorando México". www.explorandomexico.com.mx. Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ "Curiosidades del Constituyente de Querétaro (1916-1917)". www.proceso.com.mx (in Spanish). Retrieved November 24, 2024.

- ^ Sánchez, Martín (2007). Jacona. Historia de un pueblo y su desencuentro con el agua. Colegio de Michoacán, UMSNH-INAH.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Junto Con El Crecimiento De La Ciudad, Crecen También Los Servicios Públicos Municipales Con Calidad En Beneficio De Los Habitantes Del Municipio" [Together with the growth of the city, grow also the municipal public services with quality to Benedit the inhabitants of the municipality] (in Spanish). Querétaro: Municipality of Querétaro. July 30, 2007. Retrieved November 12, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Querétaro, emblema de México: Le Figaro". Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- ^ "Boom en El Bajío, nuevo polo industrial de México". June 2, 2013.

- ^ "Querétaro atrae los centros de datos | Datacenter Dynamics". Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c Beltran, Maria Elena Peyro; Medina, Martha Virginia Gonzalez; Perez, Angelina Hernandez (May 2, 2019). "La inversión asiática en el sector automotor de la región del Bajío, México". Expresión Económica. Revista de análisis (in Spanish) (42): 29–54. doi:10.32870/eera.vi42.896. ISSN 1870-5960.

- ^ "Querétaro, el nuevo territorio japonés". El Financiero. February 26, 2014. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ "Leoneses lanzan periódico en japonés". Unión Guanajuato. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ "Japón abre consulado en León, Guanajuato". El Financiero. January 4, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ "Japoneses en Aguascalientes y en la Región / El apunte - La Jornada Aguascalientes (LJA.mx)". La Jornada Aguascalientes (LJA.mx) (in Mexican Spanish). May 23, 2017. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ "En Querétaro viven personas de 91 países". El Universal Querétaro. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- ^ Ríos, Viri (November 7, 2022). "Cómo León se convirtió en la ciudad más pobre de México" [How León became the poorest city in Mexico]. Grupo Milenio (in Mexican Spanish).

- ^ Partlow, Joshua (June 18, 2015). "Workers may be losers in Mexico's car boom". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Levin, Sandy (December 5, 2017). "The outsourcing of US jobs to low-wage Mexico". The Hill. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Brading, D.A. Haciendas and Ranchos in the Mexican Bajío: Léon, 1700-1860. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1978.

- Murphy, Michael A. Irrigation in the Bajío Region of Colonial Mexico. Boulder: Westview Press 1986.

- Ocaranza Sainz, Ignacio. Estudio geográfico y económico del Bajío, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico, 1963

- Sánchez Rodríguez, Martín, "Mexico's Breadbasket: Agriculture and the Environment in the Bajío" in Christopher R. Boyer, A Land Between Waters: Environmental Histories of Modern Mexico. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 2012, pp. 50–72.

- Wright Carr, David Charles (1999). La conquista del Bajío y los orígenes de San Miguel de Allende, Universidad del Valle de México-Fondo de Cultura Económica, México.

External links

[edit]- http://www.cuentame.inegi.org.mx/territorio/rev/index.html

- http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/mexicocifras/default.aspx?e=11&i=i

- http://www.e-local.gob.mx/work/templates/enciclo/guanajuato/hist.htm

- http://www.historicas.unam.mx/moderna/ehmc/ehmc14/187.html

- https://web.archive.org/web/20101223114649/http://www.bicentenario.gob.mx/bdb/bdbpdf/NBNM/R/23.pdf