Baháʼí Faith in North America

| Part of a series on the |

| Baháʼí Faith |

|---|

|

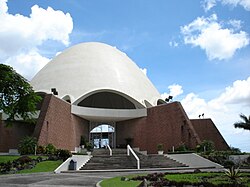

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, son of Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, visited the United States and Canada in 1912. Baháʼí Houses of Worship were completed in Wilmette, Illinois, United States in 1953 and in Panama City, Panama in 1972.

History

[edit]ʻAbdu'l-Bahá

[edit]ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, son of Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, visited the United States and Canada in 1912.[1]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote a series of letters, or tablets, to the followers of the religion in the United States in 1916–1917; these letters were compiled together in the book titled Tablets of the Divine Plan. The sixth of the tablets was the first to mention Latin American regions and was written on 8 April 1916, but was delayed in being presented in the United States until 1919—after the end of the First World War and the Spanish flu pandemic. The first actions on the part of Baháʼí community towards Latin America were that of a few individuals who made trips to Mexico and South America near or before this unveiling in 1919, including Mr. and Mrs. Frankland, and individuals who would later be appointed as Hands of the Cause like Roy C. Wilhelm, and Martha Root. The sixth tablet was translated and presented by Mirza Ahmad Sohrab on 4 April 1919, and published in Star of the West magazine on 12 December 1919.[2]

His Holiness Christ says: Travel ye to the East and to the West of the world and summon the people to the Kingdom of God.…(travel to) the Islands of the West Indies, such as Cuba, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, the Islands of the Lesser Antilles (which includes Barbados), Bahama Islands, even the small Watling Island, have great importance…[3]

Later history

[edit]In 1927 Leonora Armstrong was the first Baháʼí to visit many of these countries where she gave lectures about the religion as part of her plan to complement and complete Martha Root's unfulfilled intention of visiting all the Latin American countries for the purpose of presenting the religion to an audience.[4]

Shoghi Effendi, head of the religion after the death of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in 1921, wrote a cable on 1 May 1936 to the Baháʼí Annual Convention of the United States and Canada, and asked for the systematic implementation of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's vision to begin.[5] In his cable he wrote:

Appeal to assembled delegates ponder historic appeal voiced by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Tablets of the Divine Plan. Urge earnest deliberation with incoming National Assembly to insure its complete fulfillment. First century of Baháʼí Era drawing to a close. Humanity entering outer fringes most perilous stage its existence. Opportunities of present hour unimaginably precious. Would to God every State within American Republic and every Republic in American continent might ere termination of this glorious century embrace the light of the Faith of Baháʼu'lláh and establish structural basis of His World Order.[6]

Following the 1 May cable, another cable from Shoghi Effendi came on 19 May calling for permanent pioneers to be established in all the countries of Latin America.[5] The Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada appointed the Inter-America Committee to take charge of the preparations. During the 1937 Baháʼí North American Convention, Shoghi Effendi cabled advising the convention to prolong their deliberations to permit the delegates and the National Assembly to consult on a plan that would enable Baháʼís to go to Latin America as well as to include the completion of the outer structure of the Baháʼí House of Worship in Wilmette, Illinois. In 1937 the First Seven Year Plan (1937–44), which was an international plan designed by Shoghi Effendi, gave the American Baháʼís the goal of establishing the Baháʼí Faith in every country in Latin America. With the spread of American Baháʼís in Latin American, Baháʼí communities and Local Spiritual Assemblies began to form in 1938 across the rest of Latin America.

By 1944, every state in the United States had at least one local Baháʼí administrative body.[7] In 1946, a great pioneer movement, the Ten Year Crusade, began with, for example, sixty percent of the British Baháʼí community eventually relocating.[8]

As far back as 1951 the Baháʼís had organized a regional National Assembly for the combination of Mexico, Central America and the Antilles islands.[5] Many counties formed their own National Assembly in 1961. Others continued to be organized in regional areas growing progressively smaller. From 1966 the region was reorganized among the Baháʼís of Leeward, Windward and Virgin Islands with its seat in Charlotte Amalie.[9]

In 1953, a Baháʼí House of Worship was completed in Wilmette, Illinois.[10]

Hand of the Cause Rúhíyyih Khánum toured the Caribbean Islands for five weeks in 1970.[11]

Canada

[edit]

The Canada 2011 Census National Household Survey recorded 18,945 Baháʼís.[13] In 2018, the Bahá’í Community of Canada's official website stated it had some 30,000 members, with a Spiritual Assembly found in most of the approximately 1,200 Bahá’í communities throughout the 13 provinces and territories of Canada.[14] Canada is officially a bilingual (English-French) country, which also has a large population (roughly 5% of total) of indigenous peoples; the Bahá’í Community of Canada notes that its membership is quite diverse, French and English, more than 18% of from First Nations and Inuit backgrounds, and 30% foreign born who had immigrated to Canada.[14]

The Canadian community is one of the earliest western communities, at one point sharing a joint National Spiritual Assembly with the United States, and is a co-recipient of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Tablets of the Divine Plan. The first North American woman to declare herself a Baháʼí was Mrs. Kate C. Ives, of Canadian ancestry, though not living in Canada at the time. Moojan Momen, in reviewing "The Origins of the Baháʼí Community of Canada, 1898–1948" notes that "the Magee family... are credited with bringing the Baháʼí Faith to Canada. Edith Magee became a Baháʼí in 1898 in Chicago and returned to her home in London, Ontario, where four other female members of her family became Baháʼís. This predominance of women converts became a feature of the Canadian Baháʼí community..."[15]

Statistics Canada reports 14,730 Baháʼís from 1991 census data and 18,020 in those of 2001.[16] However the Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated almost 46,600 Baháʼís in 2005.[17] Some editions of the Canadian Baháʼí News are available.[18]

In 1909, the Baháʼís of the United States and Canada elected a nine-member Executive Committee for the Bahai Temple Unity, a continental consultative body formed to build the Baháʼí House of Worship, in Illinois, to serve as the continental temple for North America. This group also coordinated the spread of the Baháʼí Faith across North America, and reviewed Baháʼí publications for their accuracy, and in 1925 created an official National Spiritual Assembly of the United States of America and Canada. In 1948, having grown in membership and diversity, the Bahá’í Community of Canada formed its individual National Spiritual Assembly. This National Spiritual Assembly coordinates the spread of the Baháʼí Faith across Canada and reviews Baháʼí publications, publishing them through the French-English bilingual publication, Études Baháʼí Studies,[19] replaced in 1988 by the French-English-Spanish trilingual The Journal of Baháʼí Studies,[20] both of which were published in Ottawa by agencies of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Canada.[20]

United States

[edit]In 1894 Thornton Chase became the first North American Baháʼí who remained in the faith. By the end of 1894 four other Americans had also become Baháʼís. In 1909, the first National Convention was held with 39 delegates from 36 cities.[21]

In December 1999, the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States stated that out of approximately 140,000 adult (15 and over) members on the rolls, only 70,000 had known addresses.[22] The American Religious Identity Survey (ARIS) conducted in 2001, with a sample size of 50,000, estimated that there were 84,000 self-identifying adult (21 and over) Baháʼís in the United States.[23] The Association of Religion Data Archives estimated there were some 525,000 Baháʼís in 2005[17] however statistics in Feb 2011 show 175,000[24] excluding Alaska and Hawai'i.

Although a majority of Americans are Christians, Baháʼís make up the second-largest religious group in South Carolina as of May 2014[update].[25] And based on data from 2010, Baháʼís were the largest minority religion in 80 counties out of the 3143 counties in the country.[26] While early fictional works relating the religion occurred in Europe a number of them have appeared in the United States since the 1980s, sometimes in mass media - see Baháʼí Faith in fiction.

Mexico

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith in Mexico begins with visits of Baháʼís before 1916.[5] In 1919 letters from the head of the religion, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, were published mentioning Mexico as one of the places Baháʼís should take the religion to.[27] Following further pioneers moving there and making contacts the first Mexican to join the religion was in 1937, followed quickly by the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly of all Latin America being elected in 1938.[5][28] With continued growth the National Spiritual Assembly was first elected in 1961.[28][29] The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated almost 38,000 Baháʼís in 2005.[17]

Central America

[edit]Belize

[edit]The Association of Religion Data Archives estimates there were 7,776 Baháʼís in Belize in 2005, or 2.5% of the national population.[30] Their data also states that the Baháʼí Faith is the second most common religion in Belize, followed by Hinduism (2.0%) and Judaism (1.1%).[31] The 2010 Belize Population Census recorded 202 Baháʼís.[32][33]

Costa Rica

[edit]The first pioneers began to settle in Coast Rica in 1940.[28] followed quickly by the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly being elected in San José in April 1941.[5] The National Spiritual Assembly was first elected in 1961.[29] Baháʼís sources as of 2009 the national community includes various peoples and tribes of over 4,000 members organized in groups in over 30 locations throughout the country.[28] The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying mostly on the World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 13,000 Baháʼís in 2005.[17]

Panama

[edit]

The history of the Baháʼí Faith in Panama begins with a mention by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in the book Tablets of the Divine Plan, published in 1919; the same year, Martha Root made a trip around South America and included Panama on the return leg of the trip up the west coast.[34] The first pioneers began to settle in Panama in 1940.[28] The first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly of Panama, in Panama City, was elected in 1946,[5] and the National Spiritual Assembly was first elected in 1961.[29] The Baháʼís of Panama raised a Baháʼí House of Worship in 1972.[35] In 1983 and again in 1992, some commemorative stamps were produced in Panama[36][37] while the community turned its interests to the San Miguelito and Chiriquí regions of Panama with schools and a radio station.[38] The Association of Religion Data Archives estimated there were some 41,000 Baháʼís in 2005[17] while another sources places it closer to 60,000.[39]

Caribbean

[edit]Barbados

[edit]The first Baháʼí to visit Barbados was Leonora Armstrong in 1927[4] while pioneers who moved to the island arrived by 1964.[40] With local converts they elected the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly in 1965.[41] During October 1966 a trip to ten islands was planned by Lorraine Landau, a pioneer in Barbados.[42] Hand of the Cause ʻAlí-Muhammad Varqá attended the inaugural election of the Barbados Baháʼís National Spiritual Assembly in 1981.[43] Since then Baháʼís have participated in several projects for the benefit of the wider community and in 2001 various sources report up to 1.2% of the island,[44] about 3,500 citizens are Baháʼís[45] though Baháʼí and government census data report far lower numbers.[46][47] In fact, the 2010 Barbados census recorded 178 Baháʼís out of a total population of 250,010.[48]

Dominica

[edit]The island of Dominica was specifically listed as an objective for plans on spreading the religion in 1939 Shoghi Effendi,[49] who succeeded ʻAbdu'l-Baha as head of the religion. In 1983 Bill Nedden is credited with being the first pioneer to Dominica at the festivities associated with the inaugural election of the Dominican Baháʼís National Spiritual Assembly[43] with Hand of the Cause, Dhikru'llah Khadem representing the Universal House of Justice. Since then Baháʼís have participated in several projects for the benefit of the wider community and in 2001 various sources report between less than 1.4%[50] up to 1.7% of the island's about 70,000 citizens are Baháʼís.[45]

Haiti

[edit]The first Baháʼí to visit Haiti was Leonora Armstrong in 1927.[51] After that others visited until Louis George Gregory visited in January 1937 and he mentions a small community of Baháʼís operating in Haiti.[52] The first long term pioneers, Ruth and Ellsworth Blackwell, arrived in 1940.[53] Following their arrival the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly of Haiti was formed in 1942 in Port-au-Prince.[54] From 1951 the Haitian Baháʼís participated in regional organizations of the religion[55] until 1961 when Haitian Baháʼís elected their own National Spiritual Assembly[56] and soon took on goals reaching out into neighboring islands.[57] The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying mostly on the World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 23000 Baháʼís in Haiti in 2005.[17]

Jamaica

[edit]The community of the Baháʼís begins in 1942 with the arrival of Dr. Malcolm King.[58] The first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly of Jamaica, in Kingston, was elected in 1943.[59] By 1957 the Baháʼís of Jamaica were organized under the regional National Spiritual Assembly of the Greater Antilles, and on the eve of national independence in 1962, the Jamaica Baháʼís elected their own National Spiritual Assembly in 1961.[56] By 1981 hundreds of Baháʼís and hundreds more non-Baháʼís turned out for weekend meetings when Rúhíyyih Khánum spent six days in Jamaica.[51] Public recognition of the religion came in the form of the Governor General of Jamaica, Sir Howard Cooke, proclaiming a National Baha'i Day first on 25 July in 2003 and it has been an annual event since.[60] While there is evidence of several active communities by 2008 in Jamaica, estimates of the Baháʼís population range from the hundreds to the thousands. The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 5137 Baháʼís in 2005.[17]

Trinidad and Tobago

[edit]The Baháʼí Faith in Trinidad and Tobago begins with a mention by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, then head of the religion, in 1916 as the Caribbean was among the places Baháʼís should take the religion to.[2] The first Baháʼí to visit came in 1927[4] while pioneers arrived by 1956[61] and the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly was elected in 1957[62] In 1971 the first Baháʼí National Spiritual Assembly was elected.[63] A count of the community then noted 27 assemblies with Baháʼís living in 77 locations.[64] Since then Baháʼís have participated in several projects for the benefit of the wider community and in 2005/10 various sources report near 1.2% of the country,[65] about 10[66]–16,000[17]

See also

[edit]- Category:American Bahá'ís

- Category:Canadian Bahá'ís

- Baháʼí Faith and Native Americans

- Baháʼí Faith by country

- Religion in North America

- History of the Baháʼí Faith

Notes

[edit]- ^ Hatcher, William S.; Martin, J. Douglas (2002). The Baha'i Faith: The Emerging Global Religion. US Baha'i Publishing Trust. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-1-931847-06-3.

- ^ a b ʻAbbas, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (April 1919). Tablets, Instructions and Words of Explanation. Mirza Ahmad Sohrab (trans. and comments).

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916–17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 31–36. ISBN 0-87743-233-3.

- ^ a b c Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memoriam. Vol. XVIII. Baháʼí World Centre. pp. 733–736. ISBN 0-85398-234-1.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Lamb, Artemus (November 1995). The Beginnings of the Baháʼí Faith in Latin America:Some Remembrances, English Revised and Amplified Edition. West Linn, Oregon: M L VanOrman Enterprises.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi (1947). Messages to America. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Committee. p. 6. ISBN 0-87743-145-0. OCLC 5806374.

- ^ "U.S. Baha'i History". Baha'i Faith. Archived from the original on 19 September 2009. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- ^ U.K. Baháʼí Heritage Site. "The Baháʼí Faith in the United Kingdom –A Brief History". Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ Universal House of Justice (1966). "Ridván 1966". Ridván Messages. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ John Richardson (December 1997). "Preserving the Bahaʼi House of Worship: Unusual Mandate, Material, and Method" (PDF). Cultural Resource Management. National Park Service. p. 50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "The Great Safari of Hand of the Cause Ruhiyyih Khanum; Barbados". Baháʼí News. No. 483. June 1971. pp. 17–18.

- ^ Montreal Baháʼí Community: Locations.

- ^ "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". Statistics Canada. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Facts and Figures". The Bahá’í Community of Canada. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Origins of the Bahá'í Community of Canada 1898-1948, the, by Will C. Van den Hoonaard".

- ^ "Census data". Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Most Baha'i Nations (2005)". QuickLists > Compare Nations > Religions >. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ Canadian Baháʼí News, Bahai.works, 2018

- ^ "(for example) The Bahá'í Faith in Russia: Two Early Instances". Études Baháʼí Studies. 5. Ottawa: Canadian Association for Studies on the Baháʼí Faith. January 1979. Retrieved 11 October 2020 – via Bahá'í Library Online.

- ^ a b "The Journal of Baháʼí Studies". Association for Baháʼí Studies (North America). Ottawa: National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Canada. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Stockman, Robert H. (2001). "The Search Ends". Thornton Chase: First American Baháʼí. Wilmette, Illinois: US Baha'i Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-0877432821 – via Baháʼí Library Online.

- ^ National Teaching Committee (12 December 1999). "Issues Pertaining to Growth, Retention and Consolidation in the United States; A Report by the National Teaching Committee of the United States". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United States. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Largest Religious Groups in the United States of America". Adherents.com. 2013. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Quick Facts and Stats". Official website of the Baha'is of the United States. National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of the United States. 11 June 2014. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Reid. "The Second-Largest Religion in Each State". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Religion Census Newsletter" (PDF). RCMS2010.org. Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies. March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ ʻAbbas, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (April 1919). Tablets, Instructions and Words of Explanation. Mirza Ahmad Sohrab (trans. and comments).

- ^ a b c d e "Comunidad Baháʼí de México". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of Mexico. 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ^ a b c Hassall, Graham; Universal House of Justice. "National Spiritual Assemblies statistics 1923–1999". Assorted Resource Tools. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ^ "Most Baha'i Nations (2005)". The Association for Religion Data Archives. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "Belize: Religious Adherents (2010)". The Association for Religion Data Archives. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ "2010 Census of Belize Overview". 2011. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ "2010 Census of Belize Detailed Demographics of 2000 and 2010". 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Yang, Jiling (January 2007). In Search of Martha Root: An American Baháʼí Feminist and Peace Advocate in the early Twentieth Century (Thesis). Georgia State University. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ House of Justice, Universal; compiled by W. Marks, Geoffry (1996). Messaged from the Universal House of Justice: 1963–1986: The Third Epoch of the Formative Age. Wilmette, Illinois: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 212. ISBN 0-87743-239-2.

- ^ maintained by Tooraj, Enayat. "Baháʼí Stamps". Baháʼí Philately. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ maintained by Tooraj, Enayat. "Baháʼí Stamps". Baháʼí Philately. Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ^ International Community, Baháʼí (October–December 1994). "In Panama, some Guaymis blaze a new path". One Country. 1994 (October–December). Archived from the original on 2 August 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ "Panama". WCC > Member churches > Regions > Latin America > Panama. World Council of Churches. 1 January 2006. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ "NSA of United States Reports Status of Goals in Atlantic and Caribbean Areas; Present Status of Goals". Baháʼí News. No. 407. February 1965. p. 1.

- ^ "New Goals Won in the Caribbean Area". Baháʼí News. No. 412. July 1965. p. 9.

- ^ "A Major Event". Baháʼí News. No. 427. October 1966. p. 10.

- ^ a b Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memoriam. Vol. XVIII. Baháʼí World Centre. p. 514. ISBN 0-85398-234-1.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "International > Regions > Caribbean > Barbados > Religious Adherents". thearda.com. 2001. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ a b "Most Baha'i Nations (2005)". thearda.com. 2001. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ "Welcome to the Barbados Baha'i Website". National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of Barbados. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ "Redatam". Census. Barbados Statistical Service. 2010. Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ "Redatam". Census. Barbados Statistical Service. 2010. Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi (1947). Messages to America. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Committee. p. 25. OCLC 5806374.

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (14 September 2007). "International Religious Freedom Report – Dominica". United States State Department. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Locke, Hugh C. (1983). Baháʼí World, Vol. XVIII: 1979–1983. pp. 500–501, 629.

- ^ "Annual Report Inter-America Committee". Baháʼí News. No. 109. July 1937. pp. 3–5.

- ^ "InterAmerica Teaching". Baháʼí News. No. 139. October 1940. p. 4.

- ^ "Supplement to Annual Report of the National Spiritual Assembly 1941–42". Baháʼí News. No. 154. July 1942. pp. 11–12.

- ^ "Central America, Mexico and the Antilles". Baháʼí News. No. 247. September 1951. pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b "National Spiritual Assemblies Statistics". Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ "Teaching Conference Held in Honduras". Baháʼí News. No. 411. June 1965. p. 1.

- ^ Bridge, Abena (5 July 2000). "Divine rites – Uncovering the faiths". Jamaican Gleaner News. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012.

- ^ Baháʼí International Community (25 July 2003). "Joyous festivities in Jamaica". Baháʼí World News Service.

- ^ Baháʼí International Community (11 August 2006). "Jamaicans celebrate 4th National Baha'i Day". Baháʼí World News Service.

- ^ "The Guardian's Message to the Forty-Eighth Annual Baha'i Convention". Baháʼí News. No. 303. May 1956. pp. 1–2.

- ^ "First Local Spiritual Assembly…". Baháʼí News. No. 321. November 1957. p. 8.

- ^ "A Year of Progress in Trinidad". Baháʼí News. No. 480. March 1971. pp. 8–9.

- ^ "Outstanding Achievements, Goals". Baháʼí News. No. 484. July 1971. p. 3.

- ^ "International > Regions > Caribbean > Trinidad and Tobago > Religious Adherents". thearda.com. 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ "The History of the Baháʼí Faith in Trinidad and Tobago". The National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahai´s of Trinidad and Tobago. 2010. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Echevarria, Lynn (2011). Life Histories of Baháʼí Women in Canada: Constructing Religious Identity in the Twentieth Century. Series 7, Theology and Religion, American University Studies. Vol. 316. Peter Lang Publishing Inc. ISBN 9781433114571.

- Garlington, William (2008) [2005]. The Baha'i Faith in America. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0742562349. OCLC 1244209170.

- McMullen, Mike (2000). The Baháʼí: The Religious Construction of a Global Identity. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813528366.

- McMullen, Mike (2015). The Baháʼís of America: The Growth of a Religious Movement. NYU Press. ISBN 978-1-4798-5152-2.

- Stockman, Robert (1985). Baháʼí Faith in America: Origins 1892-1900. Wilmette, Ill.: Baha'i Publishing Trust of the United States. ISBN 978-0-87743-199-2.

- Stockman, Robert (2002). The Baháʼí Faith in America: Early Expansion, 1900-1912 Volume 2. Wilmette, Ill.: George Ronald. ISBN 978-0-87743-282-1.

- Stockman, Robert (2012). ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in America. Wilmette, Ill.: Baha'i Publishing Trust of the United States. ISBN 978-1-931847-97-1.

- van den Hoonaard, Will C. (1996). The Origins of the Bahá'í Community of Canada, 1898-1948. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 9781554584956.

- Venters, Louis (2016). No Jim Crow Church: The Origins of South Carolina's Bahá'í Community. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813054070.

- Venters, Louis (2019). A History of the Bahá'í Faith in South Carolina. The History Press. ISBN 978-1467117494.