Baháʼí Faith in France

| Part of a series on the |

| Baháʼí Faith |

|---|

|

The Baháʼí Faith in France started after French citizens observed and studied the religion in its native Persia in the mid-19th century.[1] The first followers of the religion declared their belief shortly before 1900, the community grew and the understanding of Baha'u'llah's Revelation was assisted by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's trip to France in late 1911 and early 1913.[2] The number of Baha'is grew, tests and difficulties were overcome, and the community established its National Assembly in 1958. The community has been reviewed a number of times by researchers.[3][4][5] According to the 2005 Association of Religion Data Archives data there are close to some 4,400 Baháʼís in France[6] and the French government is among the many who have been alarmed at the persecution of Baháʼís in modern Iran.[7]

Early days

[edit]Before 1900

[edit]A French agent working in Persia reported briefly on the Bábís, teachings brought by the Báb, the forerunner and Prophet-Herald of the Baháʼí Faith, in the 1840s after it originated in 1844.[8]

Though in no way espousing his beliefs, Baháʼís know Arthur de Gobineau as the person who obtained the only complete manuscript of the early history of the Bábí religious movement of Persia, written by Haji Mírzá Jân of Kashan,[1] who was put to death by the Persian authorities about 1852. The manuscript now is in the Bibliothèque Nationale at Paris. He is also known to students of the Bábí Faith for having written the first and most influential account of the movement, displaying a fairly accurate knowledge of its history in Religions et philosophies dans l'Asie centrale. An addendum to that work is a bad translation of the Báb's Bayan al-'Arabi, the first Bábí text to be translated into a European language.[1][8]

Baháʼu'lláh, founder of the Baháʼí Faith in the 19th century, addressed a number of items to French officials or in circumstances related to France from circa the 1870s. There were two Tablets to Emperor Napoleon III incorporated into major works of the literature of the Baháʼí Faith: the Súriy-i-Mulúk and the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. In the first it said the sincerity of the Emperor's claims on behalf of the oppressed and the helpless were tested. In the second he prophesies that, failing that sincerity, his kingdom would be "thrown into confusion", the "empire shall pass" from him and the people experience great "commotions".[9][10][11][12] Baháʼu'lláh also criticizes the French Ambassador in Constantinople for having conspired with the Persian Ambassador saying he has neglected the exhortations of Jesus Christ as recorded in the Gospels and advises him, and those like him, to be just and not to follow the promptings of the evil within their own selves.[13] Another tablet – the Tablet of Fu'ad – was written soon after the death of Fu'ád Páshá in Nice. The Pasha was the foreign minister of the Sultan and a faithful accomplice of the prime minister in bringing about the exile of Baháʼú'lláh to 'Akka then in Palestine.[14]

However, Baháʼu'lláh's tablets had little attention if any in France itself. Instead the French were still occupied much more with the Báb's dramatic life and the persecution his religion and life were subject to. French writer Henri Antoine Jules-Bois says that: "among the littérateurs of my generation, in the Paris of 1890, the martyrdom of the Báb was still as fresh a topic as had been the first news of his death. We wrote poems about him. Sarah Bernhardt entreated Catulle Mendès for a play on the theme of this historic tragedy."[8] The French writer A. de Saint-Quentin also mentioned the religion in a book published in 1891.[8] For all the attention, little penetrated to understanding the religion itself.[15]

In late 1894 May Bolles (later Maxwell) moved to Paris with her mother and brother, who was to attend the École des Beaux-Arts,[16] May's mother hoped the change from living in America would help May find a happy life, however she continued through periods of deep depression and insomnia and even considered entering a convent. In 1897 May lost both her grandmother and cousin whom she was very close to. At age 27, May became obsessed with mortality and became bedridden leading to many of her family members believing she was going to die.[17] In November 1898 family friend Phoebe Hearst, with Lua Getsinger and others, stopped off at Paris. Hearst was shocked to see 28-year-old May bedridden with the chronic malady which had afflicted her.[18] She invited May to sojourn to the East with her, believing the change of air to be conducive to her health. Getsinger also disclosed to May the purpose of the journey: a pilgrimage to visit the then head of the Baháʼí Faith: ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[17] They arrived in early December. Transformed by the trip in just a few days, May returned to Paris about late-December where she stayed for some time, at the request of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, living as a confirmed Baháʼí and began teaching her new faith.

1898 is considered as the first presence of the religion in France and the beginnings of the first Baháʼí community in Europe.[15][19] That is also the year the French Encyclopaedia of Larousse contained an entry on the Bábí religion.[3]

From 1900 to World War I

[edit]About 1900 Frenchman Hippolyte Dreyfus and American Laura Clifford Barney learned of the religion in Paris from Bolles.[20] Dreyfus would be the first French Baháʼí and the couple would marry a decade later.[19]

Barney went to Egypt in the spring of 1901 to see ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and returned with Mírzá Abu'l-Faḍl Gulpáygání, one of the most erudite scholars of the religion, to Paris, where Anton Haddad translated for him. At the time, Paris had the most important Baháʼí community in Europe and many of those who were becoming Baháʼís there would in later years would be famous in the religion. During Gulpaygani's time there, more than thirty became Baháʼís. From Paris Gulpaygani went to America in the autumn of 1901.[21]

At almost the same time Englishman Thomas Breakwell was also taught the religion by Bolles in the summer of 1901 in Paris.[22] At the request of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Breakwell also took up permanent residence in Paris, where he worked enthusiastically to teach the religion and help develop the first Paris Baháʼí community. Breakwell regularly corresponded with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's secretary and translator Yúnis Khán and was the first western Baháʼí to give the Huqúqu'lláh, a voluntary payment based on any wealth in excess of what is necessary to live comfortably. Breakwell died of tuberculosis on 13 June 1902, barely a year after joining the religion though his father followed him into the religion.

After learning of the Baháʼí Faith in Washington DC near 1898 Juliet Thompson traveled to Paris at the invitation of Barney's mother.[23] Later in 1901 in Paris she met Breakwell who gave her Gobineau's description in French of the Execution of the Báb which confirmed her faith. Turn of the century Paris is also where Charles Mason Remey first met Thompson when she was taking classes on the religion from Gulpáygání.

Bolles also introduced the religion to French-American Edith MacKaye who then moved from Paris to Sion, Switzerland in 1903 as the first Baháʼí to live in that country.[24] Bolles would later leave France, being married in London and moved to Canada.[20][25]

In 1903 Dreyfus went with Lua Getsinger and Edith Sanderson to see ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Over following decades Dreyfus would translate many Baháʼí writings and serve in delegations to the Shah of Persia protesting the treatment of Baháʼís.[20]

Modern Iranian government allegations against Baháʼís claim the early 20th century French Ambassador confessed that the Baháʼí Faith was a tool of colonial expansion. Baháʼí sources indicate that the French Ambassador in Tehran, greatly impressed by the teachings of the religion and by their effect upon the people who embraced them, suggested that Baháʼís might go to Tunisia and teach their religion there.[26] But it was Dreyfus that sought out permission from the French authorities for the religion to be promulgated in Tunisia.[20] Indeed, the Baháʼí Faith has never been associated with a fortification of colonial occupation or Euro-American assimilation[27] – a stance supported by anthropologist Alice Beck Kehoe, a well known researcher of Native Americans, who observed that the Baháʼí Faith is considered by its members to be a universal faith, not tied to any one particular culture, religious background, language, or even its country of origin.[27] This has been examined in issues related to Native Americans, Latin Americans[28] and sub-Saharan Africans[29] affirming this approach in Baháʼí activities.

Among the translations done by Dreyfus of Baháʼu'lláh's works are the Kitab-i-Iqan, The Hidden Words and Epistle to the Son of the Wolf. Over the same period A.L.M. Nicholas was inspired to study the Bábí Faith because of Gobineau though Nicholas was critical of his work and even reached to the point of calling himself a Bábí.[30] Nicholas translated several Bábí volumes – Persian Bayán, Arabic Bayán, and the Dalá'il-i-Sab'ih and ultimately he believed Subh-i-Azal was the rightful successor of the Bábí Faith, being deeply hurt at what he felt the Baháʼís showed towards the Báb making him but the insignificant forerunner, the John the Baptist, of Baháʼu'lláh. On learning with clarity of the independent status as a greater prophet acknowledged for the Báb late in his life he wrote:

I do not know how to thank you nor how to express the joy that floods my heart. So it is necessary not only to admit but to love and admire the Báb. Poor great Prophet, born in the heart of Persia, without any means of instruction, and who, alone in the world, encircled by enemies, succeeds by the force of his genius in creating a universal and wise religion. That Baháʼu'lláh succeeded Him eventually may be, but I want people to admire the sublimity of the Báb, who has, moreover, paid with his life, with his blood, for the reforms he preached. Cite me another similar example. At last, I can die in peace. Glory be to Shoghi Effendi who has calmed my torment and my anxieties, glory be to him who recognizes the worth of Siyyid 'Alí-Muhammad, the Báb. I am so happy that I kiss your hands that have written my address on the envelope which carried Shoghi's message. Thank you, Mademoiselle; thank you from the depths of my heart.[30]

Barney and Dreyfus worked together on the editing and translation of Some Answered Questions.[31] In 1905–06 Barney visited Persia, the Caucasus, and Russia with Dreyfus. She also wrote a play God's Heroesin 1910 depicting the story of Tahirih[32] named as a Letter of the Living who has been compared with Joan of Arc in the changes which they came to release by virtue of their examples.[32] Barney and Dreyfyus married in April 1911, when they both adopted the surname Dreyfus-Barney.

Extending the previous work in the Encyclopaedia of Larousse the Baháʼí Faith was entered into the supplement published in 1906.[33][34]

Circa 1900–1908 Marion Jack, who would go on to be well known for her work in promulgating the religion, learned of the religion in Paris from Mason Remey when she was a student studying painting and architecture.[35]

A decade after they met at Bolles' home, between the journeys of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to France, Laura and Hippolyte married, mutually hyphenated their last names, and continued to serve the religion.

The French Baháʼís were noted as contributing to the North American Baháʼí House of Worship even after facing the January 1910 Great Flood of Paris.[36]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys in France

[edit]Various memoirs cover the travels of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá including in France.[37]

First

[edit]The first European trip after leaving Acre Palestine spanned from August to December 1911, at which time he returned to Egypt for the winter. The purpose of these trips was to support the Baháʼí communities in the West and to further spread his father's teachings.[2]

When ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in Marseille, he was greeted by Dreyfus.[38] Dreyfus accompanied ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to Thonon-les-Bains on Lake Geneva that straddles France and Switzerland.[38]

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in France for a few days before going to Vevey in Switzerland. While in Thonon-les-Bains, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá met Mass'oud Mirza Zell-e Soltan, who had asked to meet ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Soltan, who had ordered the execution of King and Beloved of martyrs, was the eldest grandson of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar who had ordered the Execution of the Báb himself. Juliet Thompson, an American Baháʼí who had also come to visit ʻAbdu'l-Bahá while still in this early phase of his journeys, recorded comments of Dreyfus who heard Soltan's stammering apology for past wrongs. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá embraced him and invited his sons to lunch.[39] Thus Bahram Mírzá Sardar Mass'oud and Akbar Mass'oud, another grandson of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, met with the Baháʼís, and apparently Akbar Mass'oud was greatly affected by meeting ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[40] From then he went to Great Britain.

On return from Great Britain ʻAbdu'l-Bahá stayed in Paris for nine weeks, during which time he stayed at a residence at 4 Avenue de Camoens, and during his time there he was helped by Dreyfus, Barney, and Lady Blomfield who had come from London. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's first talk in Paris was on 16 October,[41] and later that same day guests gathered in a poor quarter outside Paris at a home for orphans by Mr and Mrs. Ponsonaille which was much praised by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá.[42]

From almost every day from 16 Oct to 26 Nov he gave talks.[41] On a few of the days, he gave more than one talk. The book Paris Talks, part I, records transcripts of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talks while he was in Paris for the first time. The substance of the volume is from notes of Lady Blomfield,[43] her two daughters and a friend.[44] While most of his talks were held at his residence, he also gave talks at the Theosophical Society headquarters, at L'Alliance Spiritaliste, and on 26 Nov he spoke at Charles Wagner's church Foyer de l-Ame.[45] He also met with various people including Muhammad ibn ʻAbdu'l-Vahhad-i Qazvini and Seyyed Hasan Taqizadeh.[46] It was during one of the meetings with Taqizadeh that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá personally first spoke on a telephone. From France he traveled through continental Europe until he returned to France and on 2 December 1911 he left France for Egypt for the winter.[45]

He later remarked that he had visited the Senate chamber of the Parliament but "did not like their system at all, ... there was a turmoil, ... two of them got up and had a fight. ...This is a fiasco! ...Call it a play and not the Parliament."[47]

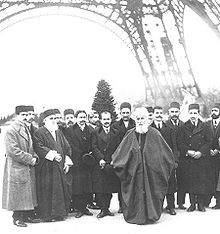

Second

[edit]ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived in Paris as part of the second journey on 22 January 1913; the visit would last for a couple months. During his stay in the city, he continued his public talks, as well as meeting with Baháʼís, including locals, those from Germany, and those who had come from the East specifically to meet with him. During this stay in Paris, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's stayed at an apartment at 30 Rue St Didier which was rented for him by (the now married) Hippolyte Dreyfus-Barney.[2]

Some of the notables that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá met while in Paris include the Persian minister in Paris, several prominent Ottomans from the previous regime, professor 'Inayatu'llah Khan, and British Orientalist E.G. Browne.[2] He also gave a talk on the evening of the 12th to the Esperantists, and on the next evening gave a talk to the Theosophists at the Hotel Moderne. He had met with a group of professors and theological students at Pasteur Henri Monneir's Theological Seminary; Pasteur Monnier was a distinguished Protestant theologian, vice-president of the Protestant Federation of France and professor of Protestant theology in Paris.[48]

Tablets of the Divine Plan

[edit]Later ʻAbdu'l-Bahá wrote a series of letters, or tablets, to the followers of the religion in the United States in 1916–1917 suggesting Baháʼís take the religion to many lands, including these. These letters were compiled in the book titled "Tablets of the Divine Plan", but its publication was delayed owing to World War I and the Spanish flu pandemic. They were translated and published in Star of the West magazine on 12 December 1919.[49] One tablet says in part:

In brief, this world-consuming war has set such a conflagration to the hearts that no word can describe it. In all the countries of the world, the longing for universal peace is taking possession of the consciousness of men. There is not a soul who does not yearn for concord and peace. A most wonderful state of receptivity is being realized.... Therefore, O ye believers of God! Show ye an effort and after this war spread ye the synopsis of the divine teachings in the British Isles, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia, Italy, Spain, Belgium, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Holland, Portugal, Rumania, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Greece, Andorra, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, San Marino, Balearic Isles, Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, Crete, Malta, Iceland, Faroe Islands, Shetland Islands, Hebrides and Orkney Islands.[50]

Development and trials

[edit]Period around the World Wars

[edit]Agnes Alexander, who had been through Paris October 1900 but encountered the religion elsewhere, was back near France as World War I broke. She was in Europe seeking passage to Japan because of directions from ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. She found opportunity as she passed through France riding in a third class coach with two wounded soldiers and arriving safely at Marseilles substituting on a ticket of a German woman.[51] Curtis Kelsey[52] and Richard St. Barbe Baker[53] were or would become Baháʼís who served in France during the First World War. Edna M. True, a Baháʼí since 1903 and daughter of (later named Hand of the Cause) Corinne True, was a member of the Smith College Relief Unit serving in France ministering to the needs of U.S. servicemen.[54]

In 1928 the first Baháʼí Local Spiritual Assembly of Paris was elected.[55] That winter Hippolyte Drefus-Barney died.[56] The funeral services included Mountfort Mills as a representative of the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and conveyed that local assemblies in the US were holding memorial services for him. In 1929–30 the first annual conference of Baháʼí Students in Paris was held.[57] In 1931 a Frenchman Gaston Hesse is noted as a staff editor of volume IV of the annual Baháʼí World periodical[58] and a number of Persian students traveled to France in part to review the places ʻAbdu'l-Bahá visited during breaks in their studies[59] until developments in 1938–39 brought that project to an end.[60] In 1936 May Maxwell (formerly Bolles) held meetings on the religion in Lyon along with Persian Mírzá Ezzatollah Zabih.[57] David Hoffman, later a member of the Universal House of Justice was able to visit Baháʼís in France in 1945. He conveyed oral reports that the Gestapo had questioned the Baháʼís of Paris. He reported the Baháʼís were able to retain some literature because they could report their office had been hit by a bomb destroying materials there but left unsaid that materials stored elsewhere were untouched. Some members of the community were still present, some had died, and some had disappeared: Miss Sanderson, Mrs. Scott, Madame Hess and Mr. Kennedy were among the living, Mrs. Kennedy died, Mlle. Alcan was killed in an air-raid, Mrs. Stannard died of cancer, and Mme Monteglore was known to have been taken to a concentration camp.[61] Some meetings were still able to be held during the occupation. French Baháʼís also assisted in the mechanics of publishing a number of translations of Baháʼí volumes by Lidia Zamenhof in Poland, Anne Lynch in Switzerland, and others in the 1930s and 40s.[62]

After World War II

[edit]The French Baháʼí community was one of the few to remain organized in Europe coming out of WWII.[10] The European Teaching Committee did not cover France as part of its responsibilities for reestablishing the religion in the countries of Europe.[63] Indeed, events noting its relative health include a new Baháʼí convert, Mme. E. Schmitt of Nancy, France, in February 1946[64] the US national assembly establishing a bureau for international news on the religion in Paris,[65] and Duncan McAlear shared news of conditions in France at the US national convention from which a decision was reached to set up a relief committee, in June.[66] In particular the Baháʼís of the southern states of America and eastern Canada coordinated relief packages for southern France (noting Marselles, Lyon, Hyeres and Toulouse) while the eastern states and again eastern Canada extended aid to the rest of France, Germany and Great Britain.[67] Fifteen contacts in Paris, three in Hyeres, two in Lyon, and one each in Marseille and Toulouse, were noted for relief shipping.[68] Marion Little pioneered to France from the US in 1947 and aided the formation of a publishing trust.[69] Six French Baháʼís are noted as still being prisoners of war in Germany where the National Spiritual Assembly of Germany petitioned for their release along with other nationals of other countries.[70] The French community was summarized as elderly and relatively few in number to compare with efforts of Baháʼís in other countries then underway[71] though it is also the oldest and continually functioning community on the continent of Europe with new converts in Lyon. Their French language materials were also being circulated around the world.[72] The religion was also noted as a presence in the French colonial empire from the 1950s. See for example Baháʼí Faith in Laos, Baháʼí Faith in New Caledonia and Baháʼí Faith in Senegal. However the Baháʼís in France remained relatively small and did not penetrate into French society[19] though Baháʼís like Dorothy Beecher Baker traveled to Paris and Lyon[73] and Lucienne Migette was noted in particular in Lyon as being very active in promulgating the religion.[74]

Indeed, Baker's trip signalized an engagement of French Baháʼís and others in progress of the religion following the troubled limits of war. French Baháʼís were in attendance at the first European Teaching Conference on 22–26 May 1948 held in Geneva which including public talks in French.[75] The second such conference, held 5–7 August 1948 in Brussels, had Migette of Lyon as one of the speakers.[76] In 1951 the Baháʼís of Paris opened a Baháʼí center open 3 days of week to visitors.[77] In 1952 fourteen Baháʼís from across Europe attended the regional conference of NGOs for the Department of Public Information of the United Nations Organizations which was held in Paris – the largest group at the conference were the Baháʼís and Baháʼí Ugo Giachery was elected chairman of one of its committees.[78] In May 1953 the first French Baháʼí conference on the promulgation of the religion was held in Lyon at which Ugo Giachery attended as well as Persians and others.[79] As part of the Ten Year Crusade Sara Kenney of France became a Knight of Baháʼu'lláh for pioneering to Medeira.[80][81] In a few years she would return and serve on the National Spiritual Assembly of France. In May 1955 the first known wave of coordinated pioneers who moved to live in new places were noted for France – eight adults went to: Orleans, Bordeaux, and Périgueux.[82] That summer Lyon hosted the first all-France Baháʼí summer school 12–20 August attracting 63 Baháʼís from 14 locations in France among others including Baháʼís from its earliest days in France as well as the new pioneers.[83] This was also the event at which the future election of the French national assembly was announced – to be in 1958. The first youth conference was held in Chateauroux in February 1956.[84] The first local assembly of Nice was elected later in 1956.[85] The second France Baháʼí Summer School, 24 August – 2 September, held at Menton-Garavan, opened with a one-day Teaching Conference which was attended by 63 adult believers, 5 youth and 15 children, representing 14 French localities and 7 countries.[86] In the spring of 1957 the first assembly of Orleans was elected.[87] Sanary-sur-Mer was the place of the next Baháʼí summer school at which 39 adults and others from many places in France as well as Kenya, Belgian Congo and Madagascar attended.[88]

National community

[edit]In 1957–58 the French community was part of the regional national assembly with the Benelux Baháʼí communities.[89] At the convention to elect the national assembly of France in 1958 was Edna True representing the US national assembly.[90][91] Hand of the Cause Herman Grossmann oversaw the convention of the delegates coming from twenty locations in France with 77 of the then 152 Baháʼís of France attending with William Sears whose travel plans landed him in France at that time.[92] The members of the first national assembly elected were: Sara Kenny, Jacques Soghomonian, Francois Petit, Joel Marangella, Chahab 'Ala'i, Sally Sanor, Lucienne Migette, Farhang Javid, and Florence Bagley. The national assembly was incorporated according to civil law in December 1958.[93] The second national convention had 17 delegates and the annual report detailed the community as seven assemblies, ten groups, and twenty isolated believers, with a membership of seventy-six French believers, thirty-eight Persians, twenty-eight Americans and eleven of other nationalities, for a total of 153 Baháʼís including nine who were new Baháʼís enrolled during the year.[94] The 1959 summer school attracted 95 attendees including 16 non-Baháʼís to Beaulieu-sur-Mer with Dr. Hermann Grossmann, as well as Jessie Revell representing the International Baháʼí Council, a predecessor to the Universal House of Justice.[95]

Division

[edit]In 1960, after the death of Shoghi Effendi, Mason Remey instigated a dispute among Baháʼís over administration and was declared a Covenant-breaker.[96] Remey succeeded in gathering a few supporters including a majority of the 1960 national assembly of France elected in April timed with Remey's announcement.[10] The assembly was dissolved through reports of Hand of the Cause Abu'l-Qásim Faizi by early May through authority of the Custodians,[96][97][98] nine Hands of the Cause assigned specifically to work at the Baháʼí World Centre elected by secret ballot, with all living Hands of the Cause voting.

An election was held to elect a new national assembly at the end of May. Its members were: Lucienne Migette, Dr. Barafroukhteh, A. Tammene, H. Samimy, Lucien McComb, A. H. Nairni, Y. Yasdanian, F. Petit, and Sara Kenny.[99] The majority of Baháʼís stood by the Hands of the Cause during this issue.[96] Over the years following 1966 the followers of Remey were not organized; several of the individuals involved began forming their own groups based on different understandings of succession.

Continued growth

[edit]Multiplying activities

[edit]The 1960 summer Baháʼí school was attended by Hands of the Cause Dr. Adelbert Mühlschlegel and Dr. Ugo Giachery with 83 attendees.[100] In October 1961 Baháʼí artist Mark Tobey was the first American to have a one-man show at the Louvre and the first in some years to win the Venice Biennale. Several of the news articles of Mark Tobey's achievement mentioned his faith as well as the 190-page catalogue of the Louvre presentation that had the most mention of the religion including Tobey's own words.[101] From Paris the show went on to London and Brussels. In December 1961 the 50th anniversary of Abdu'l-Bahá's first trip to France was commemorated at Hôtel Lutetia with an updated translation of Paris Talks.[102] The national assembly established the French Language Publishing Trust in 1962.[103]

In 1963 the members of national assemblies around the world acted as delegates to the international convention to elect the Universal House of Justice for the first time. The members of the French national assembly were: Chahab Alai, Florence Bagley, Dr. A.M. Barafroukhteh, Sara Kenny, Lucien McComb, Lucienne Migette, Yadullah Rafaat, Henriette Samimy, and Omer Charles Tamenne.[97]

Demographically the religions expanded as follows:

In 1952: 3 assemblies, 3 groups, and 6 isolated Baháʼís.[104]

In 1959: 7 assemblies, 10 groups, and 20 isolated Baháʼís.[94]

In 1963: 7 assemblies, 10 groups, and 18 isolated Baháʼís.[105]

In 1979: 31 assemblies, 61 groups, and 98 isolated Baháʼís.[106]

The 1964 Baháʼí summer school was held in Perigueux with Hand of the Cause John Ferraby in attendance.[107] In 1976 an international conference on the promulgation of the religion was held in Paris. Hand of the Cause Rúhíyyih Khanum, in her first visit to France, and representing the Universal House of Justice, attended. Some 6000 Baha'is from 55 countries attended.[108] Other Hands of the Cause also attended – Shuʼáʼu'lláh ʻAláʼí, Collis Featherstone, Dhikru'llah Khadem, Rahmatu'lláh Muhájir, John Robarts, and ʻAlí-Muhammad Varqá.[109] Other significant attendees include Amoz Gibson, then member of the Universal House, Adib Taherzadeh, then a Continental Counselor and Firuz Kazemzadeh, then member of the National Assembly of the United States. Later that year French Baha'is were noted promulgating the religion in Republic of the Congo.[110] A representative of the French national assembly attended the first election of the National Assembly of the French Antilles.[111]

Public/Media engagement

[edit]Since the inception of the Baháʼí Faith, its founder Baháʼu'lláh exhorted believers to be involvemed in socio-economic development, leading individuals to become active in various projects.[112] In France this developed from just participating in social public events but it expanded into social developments and cares which returned government appreciation and support.

In 1966 the Baháʼís participated in the International Fair in Nice handing out thousands of pieces of literature.[113] A similar exhibit took place in Marseille in later 1966.[114] A smaller one took place in late 1966 in Luchon.[115] The exhibit opportunity in Nice repeated in 1967 and was paralleled in Grenoble.[116] In 1968 the event in Nice repeated and this time an additional venue in Montpelier had a Baháʼí display present[117] while a smaller event took place in Marseille and Saint-Cloud.[118] In 1971–72 Baháʼí youth organized a proclamation comparing and the music group Seals and Crofts after their Baháʼí pilgrimage along with related publicity.[119] The same year the national assembly formally met with the mayor of Monaco officially.[120] In 1973 local efforts to promulgate the religion in the area of Clermont-Ferrand developed into television coverage between there and Switzerland on local television and it was reported most of the new converts were youth.[121] In early 1976 the national assembly sent all local assemblies a package of information suitable for public use about Baháʼí Holy Days, and Baháʼí support for observances like United Nations Day which was in turn offered to local media.[122] Meanwhile, an architecture student of I'Ecole Superieure d'Architecture de Bordeaux was able to formulate a study program on "The Baha'i Faith and Architecture" which was then in turn presented to students and faculty of the school.[123] Perhaps the first national television coverage of the religion took place during the 1976 international conference held in Paris.[109] Kurt Waldheim, then secretary-general of the United Nations, sent a message in recognition of the contributions of the Baha'is to United Nations initiatives to the conference. In 1980 the European Parliament passed a resolution concerning the Persecution of Baháʼís in Iran following the Iranian Revolution[124][125] which was echoed by then President François Mitterrand.[126] The Spiritual Assembly of Bron held a successful concert fundraiser for the United Nations International Year of the Disabled in 1981.[127] In 1983 years of contact with the Esperantists by one of the members of the Baha'i community of Nantes, France, resulted in sharing with the 25-member Assembly of the Esperanto Association copies of the "white paper" on the plight of Baha'is in Iran.[128] In later in October a French language television program featured an artist/cryptographer's calligraphy of nine letters forming the word "Behaisme". The moderator looked up the word in a dictionary and read to an audience estimated at 19 million a brief definition of the religion. The program was rebroadcast in other French-speaking countries.[129] In 1984 Baha'is from Marseilles to Nice in southern France worked to make the first Baha'i-sponsored float on the Cote d'Azur as part of municipal parades in Cavalaire and Sainte-Maxime.[130] Also in 1984 a 15-minute segment by the Baha'is of France was televised 29 September including parts of previously produced Baha'i films from several sources as one of five segments that made up an overall 75-minute program entitled Liberte 3.[131] In April 1985 a new national center was opened at a ceremony with attendees from government and NGOs – the president of the Senate, two representatives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Citoyens du Monde, the International Federation of the Rights of Man, and Amnesty International.[132] In 1984 an Association of Baha'i Health Care Professionals was organized by a number of Baha'i doctors in France with bylaws approved by the national assembly.[133] In 1986 The Promise of World Peace document was shared with political leaders in France including then Prime Minister Laurent Fabius, the president and vice-president of France's Parliament.[134] In spring 1986 Baha'is in Moontpelier and Marseilles held public peace events with panelists, children, performers, NGO representatives and others for the International Year of Peace.[135]

Modern community

[edit]In 1987 Hand of the Cause Rúhíyyih Khanum commemorated her mother's time in France with a trip visiting the Baha'is in 17 places during a 33-day stay arriving on 11 November. Events included a two-day national conference on spreading the religion held in Paris; seven regional gatherings throughout the country in Nice, Marseille, Annecy, Bordeaux, Nantes, Rennes and Strasbourg, and a national youth conference of more than 450 youth in Lyon.[136] During the visit she met with the director of the Affairs of Cultes and former president of the European Parliament, Simone Veil, former prime minister, then Speaker of its House of Representatives, Jacques Chaban-Delmas, as well as local officials. During meetings with Baha'is and visitors she often spoke of her recent trips to Africa.

Extending the background of academic interest in the religion since 1900 two volumes of the French language Catholic encyclopedia Fils d'Abraham were published in 1987 mentioning the religion:

• Longton, Joseph (1987). "Panorama des communautés juives chrétiennes et musulmanes". In Longton, Joseph (ed.). Fils d'Abraham (in French). S. A. Brepols I. G. P. and CIB Maredsous. pp. 11, 47–51 (mentions Baháʼís on). ISBN 2-503-82344-0. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

• Cannuye, Christian (1987). "Les Baháʼís". In Longton, J. (ed.). Fils d'Abraham. S. A. Brepols I. G. P. and CIB Maredsous. ISBN 2-503-82347-5.

In 1988 Baha'is held to large informational meetings on topics of internationalism and the environment.[137]

André Brugiroux, well known for traveling the countries of the world,[138] encountered the religion in 1969 in Alaska and joined it. He made a documentary film about his travels and visiting Baháʼís, versions of which have been shown since 1977[139][140] and wrote a few books published including 1984[141] and 1990[142] and has given many talks about the religion and his travels in and outside France.

The Gardeners of God – Two French journalists, Colette Gouvion and Philippe Jouvion attempted an objective and unbiased study of the Baháʼí Faith through a series interviews which was published in 1993 as "Les Jardiniers de Dieu" which was translated into English.[5]

The 75th anniversary of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's visit to Marseilles was commemorated at the Palais du Faro in 1989.[143] The centenary of the first trip in 1911 was noted at the annual Baháʼí residential school, held in Evian from 27 August to 3 September, where participants explored what it means to be "walking in the path of ʻAbdu'l-Baha" as they discussed the current activities of their communities.[144] Revised and extended work reviewing ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talks and those he met, were published as well in time with this centenary:

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (August 2011). Jan T Jasion (ed.). The Talks of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in France and Switzerland. Paris, FR: Librairie Baháʼíe. ISBN 978-2-912155-25-2.

- Jasion, Jan T (August 2011). On the Banks of the Seine:The History of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in France and Switzerland, 1911 and 1913. Paris, FR: Librairie Baháʼíe. ISBN 978-2-912155-26-9.

- Jasion, Jan T (August 2011). They all Witnessed His Triomph: A Biographical Guide to ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Western Travels. Paris, FR: Librairie Baháʼíe. ISBN 978-2-912155-32-0.

Continuing to voice its concern in 1993 the French government took up issues related to the treatment of Baha'is in modern Iran.[145] Subsequently, it voted in favor of a UN resolution in 1996 which expressed concern over a wide range of human rights violations in Iran in a resolution adopted by roll-call vote after last-minute negotiations failed to achieve consensus.[7] And the government took further steps a number of times.[146] In 2010 they supported the international community observing the treatment of arrested Baha'i leadership.[147][148] SeePersecution of Baháʼís.

In 1998 French Baháʼís attempted to address issues with Mohammad Khatami.[149]

Frequency 19 is a French language Baháʼí radio and video station on the internet.[150]

Demographics

[edit]According to 2005 Association of Religion Data Archives data there are about 4,440.[6]

Further research

[edit]- Julio Savi (28 August 2016). Dawning of the Baha'i Faith on the European Subcontinent (Youtube). Wilmette Institute.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, by Nader Saiedi: Review by Stephen Lambden, published in The Journal of the American Oriental Society, 130:2, 2010–04

- ^ a b c d Balyuzi, H. M. (2001), ʻAbdu'l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant of Baháʼu'lláh (Paperback ed.), Oxford, UK: George Ronald, pp. 159–397, 373–379, ISBN 0-85398-043-8

- ^ a b Larousse, Pierre; Augé, Claude (1898). "Babisme". Nouveau Larousse illustré: dictionnaire universel encyclopédique. p. 647. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Cannuye, Christian (1987). "Les Baháʼís". In Longton, J. (ed.). Fils d'Abraham. S. A. Brepols I. G. P. and CIB Maredsous. ISBN 2-503-82347-5.

- ^ a b Gouvion, Colette; Jouvion, Philippe (1993). The Gardeners of God: an encounter with five million Baháʼís (trans. Judith Logsdon-Dubois from "Les Jardiniers de Dieu" published by Berg International and Tacor International, 1989). Oxford, UK: Oneworld. ISBN 1-85168-052-7.

- ^ a b "Most Baháʼí Nations (2005)". QuickLists > Compare Nations > Religions >. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ a b UN Commission expresses concern over human rights violations in Iran

- ^ a b c d Early Western Accounts of the Babi and Baháʼí Faiths by Moojan Momen

- ^ Baháʼu'lláh (1873). The Kitáb-i-Aqdas: The Most Holy Book. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-85398-999-0.

- ^ a b c de Vries, Jelle (2002). The Babi Question You Mentioned--: The Origins of the Baháʼí Community of the Netherlands, 1844–1962. Peeters Publishers. pp. 40, 47, 52, 93, 97, 113, 133, 149, 153, 170, 175, 201, 248, 265, 290, 291, 295, 347. ISBN 978-90-429-1109-3.

- ^ "Overview of the Tablets to Napoleon". Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ Winters, Jonah (17 October 2003). "Second Tablet to Napoleon III (Lawh-i-Napulyún): Tablet study outline". Study Guides. Baha'i Library Online. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ Taherzadeh, A. (1977). The Revelation of Baháʼu'lláh, Volume 2: Adrianople 1863–68. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-071-3.

- ^ "Three Momentous Years of the Heroic Age −1868-70". Baháʼí News. No. 474. September 1970. pp. 5–9.

- ^ a b Bibliographie des ouvrages de langue française mentionnant les religions babie ou bahaʼie (1844–1944) compiled by Thomas Linard, published in Occasional Papers in Shaykhi, Babi and Baháʼí Studies, 3, 1997–06

- ^ Van den Hoonaard; Willy Carl (1996). The Origins of the Baháʼí Community of Canada, 1898–1948. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 36–39. ISBN 0-88920-272-9.

- ^ a b Nakhjavani, Violette (1996). Maxwells of Montreal, The. George Ronald. pp. 52, 70. ISBN 978-0-85398-551-8.

- ^ Hogenson, Kathryn J. (2010), Lighting the Western Sky: The Hearst Pilgrimage & Establishment of the Baha'i Faith in the West, George Ronald, p. 60, ISBN 978-0-85398-543-3

- ^ a b c Warburg, Margit (2004). Peter Smith (ed.). Baháʼís in the West. Kalimat Press. pp. 5, 10, 12, 15, 22, 36, 37, 79, 187, 188, 229. ISBN 1-890688-11-8.

- ^ a b c d Biography of Hippolyte Dreyfus-Barney by Laura C. Dreyfus-Barney and Shoghi Effendi, edited by Thomas Linard, 1928

- ^ Mirza Abu'l-Faḍl by Moojan Momen

- ^ Philip Hainsworth, 'Breakwell, Thomas (1872–1902)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 21 November 2010

- ^ "Early American Baháʼís Honor Juliet Thompson at Memorial Service in House of Worship". Baháʼí News. No. 313. March 1957. pp. 10–11.

- ^ Vader, John-Paul (27 October 2009). "Selected episodes from the early history of the Baháʼí Faith in Switzerland" (PDF). Ezri Center for Iran and Persian Gulf Studies, University of Haifa. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ Van den Hoonaard, Will C. (1996). The Origins of the Baháʼí Community of Canada; 1898–1948. Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 185, 273. ISBN 978-0-88920-272-6.

- ^ "BIC rebuts Iran's anti-Baha'i document". Baháʼí News. No. 626. May 1983. pp. 1–5.

- ^ a b Addison, Donald Francis; Buck, Christopher (2007). "Messengers of God in North America Revisited: An Exegesis of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's Tablet to Amír Khán" (PDF). Online Journal of Baháʼí Studies. 01. London: Association for Baháʼí Studies English-Speaking Europe: 180–270. ISSN 1177-8547. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ^ "Historical Background of the Panama Temple". Baháʼí News. No. 493. April 1972. p. 2.

- ^ "United States Africa Teaching Committee; Goals for this year". Baháʼí News. No. 283. June 1954. pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b The Báb (6 April 2006). "The Seven Proofs; Preface – The Work of A.L.M. Nicholas (1864–1937)". Provisional translations. A. L. M. Nicolas and Peter Terry (trans.). Baha'i Library Online. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ al-Nūr al-abhā fīmofāważāt ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Leiden, 1908; tr. L. C. Barney and H. Dreyfus as Some Answered Questions, London, 1908; "Literary News of Philadelphia". The New York Times. 17 October 1908. p. 27. Retrieved 29 December 2011. tr. H. Dreyfus asLes leçons de Saint Jean d'Acre, Paris, 1909).

- ^ a b Āfāqī, Ṣābir (2004). Táhirih in history: perspectives on Qurratu'l-'Ayn from East and West. Kalimat Press. pp. 36, 68. ISBN 978-1-890688-35-6.

- ^ Larousse, Pierre; Augé, Claude (1906). "Babisme". Nouveau Larousse illustré: dictionnaire universel encyclopédique. Vol. Supplement. p. 66. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1909). Tablets of Abdul-Baha ʻAbbas. Chicago, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Committee. p. 1.

- ^ "Memorial at Temple to Marion Jack". Baháʼí News. No. 282. August 1954. pp. 4–5.

- ^ True, Corinne (9 April 1910). Windust, Albert R; Buikema, Gertrude (eds.). "The Mashrak-el-Azkar". Star of the West. 01 (2). Chicago, USA: Baháʼí News Service: 5. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Note several volumes covering the talks given on ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys are of incomplete substantiation—"The Promulgation of Universal Peace", "Paris Talks" and "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in London" contain transcripts of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's talks in North America, Paris and London respectively. While there exists original Persian transcripts of some, but not all, of the talks from "The Promulgation of Universal Peace", "Paris Talks", there are no original transcripts for the talks in "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in London". See"Authenticity of some Texts". Baháʼí Library. 22 October 1996. Retrieved 14 March 2010..

- ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (2006). Paris Talks: Addresses Given by Abdul-Baha in 1911. UK Baháʼí Publishing Trust. ISBN 978-1-931847-32-2.

- Blomfield, Lady (1975) [1956]. The Chosen Highway. London, UK: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. pp. 147–187, Part III (ʻAbdu'l-Bahá), ChaptersʻAbdu'l-Bahá in London and ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Paris. ISBN 0-87743-015-2.

- Thompson, Juliet; Marzieh Gail (1983). The diary of Juliet Thompson. Kalimat Press. pp. 147–223, Chapter With ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Thonon, Vevey, and Geneva. ISBN 978-0-933770-27-0.

- ^ a b "Hippolyte Dreyfus, apôtre d'ʻAbdu'l-Bahá; Premier bahá'í français". Qui est ʻAbdu'l-Bahá ?. Assemblée Spirituelle Nationale des Baháʼís de France. 9 July 2000. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ Thompson, Juliet; Marzieh Gail (1983). The diary of Juliet Thompson. Kalimat Press. pp. 147–223, Chapter With ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Thonon, Vevey, and Geneva. ISBN 978-0-933770-27-0.

- ^ Honnold, Annamarie (2010). Vignettes from the Life of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. UK: George Ronald. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-85398-129-9. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ a b ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1995) [1912]. Paris Talks (Hardcover ed.). Baháʼí Distribution Service. pp. 15–17. ISBN 1-870989-57-0.

- ^ Beede, Alice R. (7 February 1912). Windust, Albert R; Buikema, Gertrude (eds.). "A Glimpse of Abdul-Baha in Paris". Star of the West. 02 (18). Chicago, USA: Baháʼí News Service: 6, 7, 12. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ "Memorial to a shining star". Baháʼí International News Service. Baháʼí International Community. 10 August 2003. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ Abdu'l-Bahá (1916). Lady Blomfield; M. E. B.; R. E. C. B.; B. M. P. (eds.). Talks by Abdul Baha Given in Paris. G. Bell and Sons, LTD. p. 5.

- ^ a b ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1995) [1912]. Paris Talks (hardcover ed.). Baháʼí Distribution Service. pp. 119–123. ISBN 1-870989-57-0.

- ^ Taqizadeh, Hasan; Muhammad ibn ʻAbdu'l-Vahhad-i Qazvini (1998) [1949]. "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá Meeting with Two Prominent Iranians". Published academic articles and papers. Bahai Academic Library. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ Fareed, Dr. Ameen (9 April 1910). Windust, Albert R; Buikema, Gertrude (eds.). "Wisdom-Talks of Abdul-Baha". Star of the West. 03 (3). Chicago, USA: Baháʼí News Service: 7. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ Fazel, Seena (1993). "ʻAbdu'l-Bahá on Christ and Christianity". Baháʼí Studies Review. 03 (1). Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ ʻAbbas, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (April 1919). Tablets, Instructions and Words of Explanation. Translated by Mírzá Ahmad Sohrab.

- ^ ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (1991) [1916–17]. Tablets of the Divine Plan (Paperback ed.). Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 43. ISBN 0-87743-233-3.

- ^ "Agnes Alexander: 70 years of service". Baháʼí News. No. 631. October 1983. pp. 6–11. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "CABLEGRAM RECEIVED FROM HAIFA, ISRAEL". Baháʼí News. No. 469. April 1970. p. 12.

- ^ "Richard St. Barbe Baker: 1889–1982". Baháʼí News. No. 469. October 1982. p. 7.

- ^ "Edna M. True: 1888–1988". Baháʼí News. No. 94. January 1988. pp. 2–3. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ The Baháʼí World: A Biennial International Record, Volume II, 1926–1928 (New York City: Baháʼí Publishing Trust, 1928), 182–85.

- ^ "Distinguished, beloved servant passes away". Baháʼí News. No. 29. January 1929. pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b May Ellis Maxwell, compiled by Universal House of Justice, published in A Compendium of Volumes of the Baháʼí World I-XII, 1925–1954, pp. 516–28

- ^ "The Baháʼí World (Volume Four)". Baháʼí News. No. 51. April 1931. p. 13.

- ^ "Baháʼí activities in other countries; France". Baháʼí News. No. 55. September 1931. p. 6.

- ^ "News of East and West". Baháʼí News. No. 139. October 1940. p. 11.

- ^ "News from other lands; France". Baháʼí News. No. 176. November 1944. pp. 17–18.

- ^ "Memorial services honor Mrs. Anne Lynch". Baháʼí News. No. 430. January 1967. p. 2.

- ^ "News from other lands; France". Baháʼí News. No. 194. April 1947. p. 9.

- ^ "European survey; France". Baháʼí News. No. 180. February 1946. p. 8.

- ^ "Distribution of Baháʼí News". Baháʼí News. No. 180. June 1946. p. 2.

- ^ "Highlights of the Convention". Baháʼí News. No. 180. June 1946. pp. 4–6.

- ^ "International Relief; What and Where to send". Baháʼí News. No. 185. July 1946. p. 10.

- ^ "National Committees; France". Baháʼí News. No. 186. August 1946. pp. 3–5.

- ^ "Passing of Pioneer Mrs. Marion Little". Baháʼí News. No. 506. May 1973. p. 13.

- ^ "Excerpts from 'Geneva Exchange'". Baháʼí News. No. 186. June 1947. p. 4.

- ^ "Mildred Mottahedeh visits ten European countries". Baháʼí News. No. 200. October 1947. p. 9.

- ^ "Correction – Paris". Baháʼí News. No. 203. January 1948. p. 7.

- ^ "European enrollments increase". Baháʼí News. No. 205. March 1948. p. 9.

- ^ "A view of pioneering". Baháʼí News. No. 205. March 1948. pp. 9–10, 12.

- ^ "European Baháʼís hold first Teaching Conference". Baháʼí News. No. 209. July 1948. p. 1.

- ^ "Second European Teaching Conference". Baháʼí News. No. 209. August 1949. p. 7.

- ^ "Around the World; France". Baháʼí News. No. 243. May 1951. p. 8.

- ^ "U.N Regional Conference in Paris". Baháʼí News. No. 252. February 1952. pp. 13–14.

- ^ "International News; France". Baháʼí News. No. 269. July 1953. pp. 13–14.

- ^ Triple Announcement on Conclusion of Holy Year Messages to the Baháʼí World: 1950–1957, pp. 169–171

- ^ "The Passing of two Knighs of Baháʼu'lláh". Baháʼí News. No. 452. November 1968. p. 3.

- ^ "Twelfth Pioneering Report". Baháʼí News. No. 291. May 1955. pp. 7–8.

- ^ "Summer Schools and Conferences of Europe 1955; All-France Conference and Summer School". Baháʼí News. No. 296. October 1955. pp. 8–10.

- ^ "Youth Conference held in Chateauroux...". Baháʼí News. No. 302. April 1956. p. 6.

- ^ "Local Assembly of Nice...". Baháʼí News. No. 306. August 1956. p. 9.

- ^ "International News ; Many Baháʼís attend France Summer School". Baháʼí News. No. 306. December 1956. pp. 6–7.

- ^ "Newly established Local Spiritual Assembly of Orleans...". Baháʼí News. No. 318. August 1957. p. 8.

- ^ "International Committees; Summer School prepares France for formation of National Assembly". Baháʼí News. No. 332. December 1957. pp. 6–7.

- ^ National Spiritual Assemblies: Lists and years of formation by Graham Hassall, 2000–01

- ^ "First Reports of the 1958 National Conventions Reveal Baháʼís, Newly Aware of Spiritual Forces Released by Guardian's Ascension, Resolve to Meet Challenges With Maturity, Audacity, and Dedication; United States; International Goals". Baháʼí News. No. 332. June 1958. p. 12.

- ^ "Message From the Hands of the Holy Land to the First All-France Convention". Baháʼí News. No. 329. July 1958. pp. 15–16.

- ^ "First National Spiritual Assembly of France, Formed Ridvan 1958, Becomes Twenty-Seventh Pillar of Faith of Baháʼu'lláh". Baháʼí News. No. 329. July 1958. pp. 17–18.

- ^ "First National Spiritual Assembly of France, Formed Ridvan 1958, Becomes Twenty-Seventh Pillar of Faith of Baháʼu'lláh". Baháʼí News. No. 340. June 1958. p. 10.

- ^ a b "Annual Conventions Review Achievements of Past Year, Marshal Forces to Attain Remaining Crusade Goal; France". Baháʼí News. No. 341. July 1959. pp. 16–17.

- ^ "Ninety-Five Baháʼís, Contacts Participate in Baháʼí Summer School of France". Baháʼí News. No. 347. January 1960. p. 4.

- ^ a b c Momen, Moojan (2003). "The Covenant and Covenant-Breaker". bahai-library.com. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ a b Rabbani, R., ed. (1992). The Ministry of the Custodians 1957–1963. Baháʼí World Centre. pp. 197, 202–227, 409. ISBN 0-85398-350-X.

- ^ "An Impregnable World Community". Baháʼí News. No. 352. July 1960. pp. 1–2.

- ^ "NSA of Frame Elected". Baháʼí News. No. 355. October 1960. p. 2.

- ^ "Two Hands of the Cause inspire Baháʼís at Fifth Summer School of France". Baháʼí News. No. 356. November 1960. pp. 5–6.

- ^ "Faith gains renown through Baháʼí Artist's Exhibition at Louvre". Baháʼí News. No. 371. February 1962. pp. 12–13.

- ^ "Abdu'l-Bahá's first visit to Europe Commemorated in Paris". Baháʼí News. No. 372. March 1962. p. 2.

- ^ "French Language Publishing Trust Has New Headquarters". Baháʼí News. No. 492. April 1972. p. 24.

- ^ "International News; France". Baháʼí News. No. 260. October 1952. pp. 13–14.

- ^ The Baháʼí Faith: 1844–1963: Information Statistical and Comparative, Including the Achievements of the Ten Year International Baháʼí Teaching & Consolidation Plan 1953–1963, Compiled by Hands of the Cause Residing in the Holy Land, pp. 46, 82.

- ^ "Victory Messages – The Baha'I world resounds with the glorious news of Five Year Plan victories". Baháʼí News. No. 581. August 1979. p. 10. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "Baháʼí Summer School Held in Perigueux, France". Baháʼí News. No. 405. March 1962. p. 5.

- ^ "Paris Conference site is selected". Baháʼí News. No. 538. January 1976. p. 14.

- ^ a b "Preparation for the Harvest; The International Teaching Conference in Paris". Baháʼí News. No. 546. September 1976. pp. 2–5.

- ^ "Around the World; Baha'is teach in Kinkala". Baháʼí News. No. 550. January 1977. p. 2.

- ^ "French Antilles". Baháʼí News. No. 555. June 1977. p. 7.

- ^ Momen, Moojan. "History of the Baháʼí Faith in Iran". draft "A Short Encyclopedia of the Baháʼí Faith". Bahai-library.com. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ^ "Baháʼí display at the International Faith in Nice...". Baháʼí News. No. 424. July 1966. p. 19.

- ^ "Marseille exhibit proclaims Faith to thousands". Baháʼí News. No. 427. October 1966. p. 3.

- ^ "French school proclaims faith to hundreds". Baháʼí News. No. 429. December 1966. p. 13.

- ^ "French proclamation in two major cities". Baháʼí News. No. 436. July 1967. p. 18.

- ^ "French exhibits in Nice, Montpelier draw crowds". Baháʼí News. No. 447. June 1968. p. 7.

- ^ "News Briefs". Baháʼí News. No. 450. September 1968. p. 15.

- ^ "Recent French Activities". Baháʼí News. No. 492. March 1972. p. 14.

- ^ "Mayor of Monaco Receives Baha'is". Baháʼí News. No. 504. March 1973. p. 24.

- ^ "A working holiday in the villages of France". Baháʼí News. No. 511. October 1973. pp. 22–3.

- ^ "Media campaign has good results". Baháʼí News. No. 541. March 1976. p. 18.

- ^ "Architecture student talks about Faith". Baháʼí News. No. 542. May 1976. pp. 8–9.

- ^ "SUPPORT-In Strasbourg, France, the European Parliament strongly condemns Iran's persecution of Baha'is". Baháʼí News. No. 542. March 1981. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Resolution on the solution of the Persecution of the members of the Bahai Community in Iran Official Journal C 265, 13 October 1980 P. 0101

- ^ "Summary of the actions taken by the Baha'i International Community, National and Local Baha'i Institutions, Governments, Non-Baha'i Organizations and prominent people in connection with the persecution of the Baha'is of Iran". Baháʼí News. No. 542. April 1982. pp. 2–3.

- ^ "Around the World; France". Baháʼí News. No. 603. March 1981. p. 11. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "The World; France". Baháʼí News. No. 630. November 1983. p. 16. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "The World; France". Baháʼí News. No. 636. March 1984. p. 12. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "The World; France". Baháʼí News. No. 643. October 1984. p. 14. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "The World; France". Baháʼí News. No. 650. May 1985. p. 14. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "The World; France". Baháʼí News. No. 652. August 1985. p. 14. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "Social/economic development – Part II of our world-wide survey; Europe/France". Baháʼí News. No. 661. April 1986. p. 13. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "The World; France". Baháʼí News. No. 664. July 1986. p. 16. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "Special Report; The International Year of Peace; France". Baháʼí News. No. 678. September 1987. p. 5. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "Special report – Recounting a memorable visit to France". Baháʼí News. No. 424. March 1988. pp. 1–3.

- ^ "Special Report; The International Year of Peace; France". Baháʼí News. No. 692. November 1988. p. 15. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ Great Modern Travelers: André Brugiroux

- ^ "French Baha'i visits Haiti". Baháʼí News. No. 553. April 1977. p. 13. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ "The World; France". Baháʼí News. No. 692. November 1988. p. 15. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ Brugiroux, André (1984). Le prisonnier de Saint-Jean-d'Arce. Albatros.

- ^ Brugiroux, André (1990). One People, One Planet: The Adventures of a World Citizen (illustrated ed.). Oneworld. ISBN 978-1-85168-029-0.

- ^ "The World; France". Baháʼí News. No. 697. June 1989. p. 14. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ European Baha'is mark centenary of ʻAbdu'l-Baha's journeys 3 October 2011

- ^ Chronology for Baha'is in Iran

- ^ "Trial with seven Baha'i leaders in Iran". Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ de Mme Ashton – Dégradation de la situation des droits de lʼhomme[permanent dead link] (12 juin 2010)

- ^ of expression, religion and belief – Iran: Sentencing of seven Baha'i leaders to 20 years in prison (10 August 2010)

- ^ Bahais warn of fresh persecution in Iran, CNN Cable News Network

- ^ "FREQUENCE 19". Licence Libre CeCILL. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

External links

[edit]- Official Website of the National Spiritual Assembly of France

- Historique des débuts de la foi baha'ie à Marseille, 1911

- Diaporama sur les débuts de la foi baha'ie en France, 1911–1913, Par lili & Bernard Lo Cascio

- Les Baha'is de Chambéry