Padshahnama

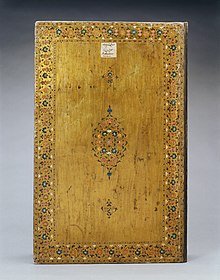

The cover of the Windsor Padshahnama | |

| Author | Muhammad Amin Qazvini Jalaluddin Tabatabai Abdul Hamid Lahori |

|---|---|

| Language | Persian |

| Genre | Biography |

| Set in | 17th century Mughal India |

| Publisher | Muhammad Waris |

Publication date | 1630–1637 |

| Publication place | Mughal Empire (India) |

| Text | Padshahnama at Wikisource |

Padshahnama or Badshah Nama (Persian: پادشاهنامه or پادشاهنامه; lit. 'The Book of the Emperor') is a group of works written as the official history of the reign of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan I. Unillustrated texts are known as Shahjahannama, with Padshahnama used for the illustrated manuscript versions. These works are among the major sources of information about Shah Jahan's reign. Lavishly illustrated copies were produced in the imperial workshops, with many Mughal miniatures. Although military campaigns are given the most prominence, the illustrations and paintings in the manuscripts of these works illuminate life in the imperial court, depicting weddings and other activities.

The most significant work of this genre was written by Abdul Hamid Lahori, the pupil of Akbar's biographer Abdul Fazal, in two volumes. He could not write the third volume of this genre because of the infirmities of old age. [1]

History

[edit]

Shah Jahan in his eighth regnal year asked Muhammad Amin Qazvini to write an official history of his reign and he completed his Badshahnama in 1636, which covers the first ten (lunar) years of Shah Jahan’s reign.[1]

Jalaluddin Tabatabai wrote another Badshahnama, but the extant portion of the text covers only four years, from fifth to eighth regnal year of the emperor. The project was later given to Abdul Hamid Lahori, who wrote his Badshahnama in two volumes. The first volume of this work is based upon Qazvini’s work but has more details. The second volume covers the next ten (lunar) years of Shah Jahan’s reign. He completed his work in 1648. Lahori died in 1654. Muhammad Waris, a pupil of Lahori was given the responsibility to complete the task and his Badshahnama (completed in 1656) covers the rest of the period of Shah Jahan’s reign. His work was published by the Asiatic Society as the third volume of the Badshahnama of Lahori.

Extant manuscripts

[edit]In 1799, Saadat Ali Khan II, the Nawab of Awadh in northern India, sent the Badshahnama, to King George III of Great Britain. Today, the imperial illustrated manuscript of the Badshahnama of Lahori is preserved in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, and is known as the Windsor Padshahnama. It was produced between 1630 and 1657 and contains 44 miniatures, some full page narrative scenes of battles, court ceremonies and other events (11 are across two pages), and some smaller individual portraits, surrounded by geometric decoration. These illustrate the genealogy of the Mughal dynasty which begins the work. The page size is 58.6 x 36.8 cm, and 13 different lead artists worked on the volume.[2] In 1994, while the volume was being rebound for conservation reasons, the opportunity was taken to tour all the miniatures in an exhibition that was shown in New Delhi, the Queen's Gallery in London, and six American cities.[3]

Manuscripts of the Badshahnamas of Qazvini and Waris are preserved in the British Library. The original manuscript of the Badshah Nama that depicts the complete reign of Shah Jahan is preserved in Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Library, Patna, India.[4]

Other individual miniatures are held in a number collections. The Khalili Collection of Islamic Art has one miniature in which Shah Jahan and his court watch two elephants fighting.[5] There were some later illustrated manuscript copies made; for example the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has miniatures from 17th-century versions, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art from one of around 1800.

Context

[edit]The Padshahnama fits into a tradition of imperial autobiographies or official court biographies, seen in various parts of the world.[citation needed] In South Asia these go back to the Ashokavadana and Harshacharita from ancient India, and the medieval Prithviraj Raso. The Mughals' ancestor Timur had been celebrated in a number of works, mostly called Zafarnama ("Book of Victories"), such as those by Shami and Yazdi. The latter is the best known, and was also produced in an illustrated copy in the 1590s by Akbar's workshop. The tradition was continued by the Mughals with the Baburnama (autobiography, not illustrated before Akbar), Akbarnama (biography), and Tuzk-e-Jahangiri or Jahangir-nameh (memoirs of Jahangir).

Gallery

[edit]-

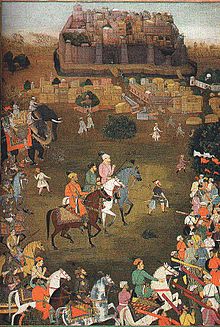

The Mughal commander Khan Dauran captures the Fort at Udgir.

-

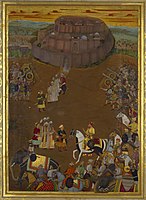

The Mughal Army captures Daulatabad fort in the year 1633.

-

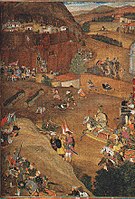

Mughal commander Azim Khan captures Dharur.

Texts online

[edit]- Lahori, Abdul Hamid (1875). Badshanama of Abdul Hamid Lahori. tr. by Henry Miers Elliot. Hafiz Press, Lahore.

- Bádsháh-Náma of 'Abdu-L Hamíd Láhorí Packard Humanities Institute

References

[edit]- ^ a b Majumdar, R. C. (ed.) (2007). The Mughul Empire, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, ISBN 81-7276-407-1, p.9

- ^ "The Padshahnama 1656-57", Royal Collection

- ^ Review of Beach, Milo C. and Ebba Koch, The King of the World: The Badshahnama: An Imperial Mughal Manuscript from the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, Thames & Hudson. 1997, in The Court Historian, Volume 4, 1999 - Issue 3, [1]

- ^ "Islamic knowledge house, Khuda Bakhsh Library retains glory". Outlook. Jul 8, 2005. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013.

- ^ Rogers, J. M. (2008). The arts of Islam : treasures from the Nasser D. Khalili collection (Revised and expanded ed.). Abu Dhabi: Tourism Development & Investment Company (TDIC). p. 280. OCLC 455121277.

- ^ Abdul Hamid Lahori (1636). "Prince Awrangzeb (Aurangzeb) facing a maddened elephant named Sudhakar". Badshahnama. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ Abdul Hamid Lahori. "Shah Jahan Receives Persian Ambassadors". Badshahnama.

- ^ Ebba Koch (1994), Diwan-i 'Amm and Chihil Sutun: The Audience Halls of Shah Jahan, p.1

Further reading

[edit]- Beach, Milo C. and Ebba Koch, The King of the World: The Badshahnama: An Imperial Mughal Manuscript from the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, Thames & Hudson. 1997. ISBN 0-500-97448-9.

- Kossak, Steven (1997). Indian court painting, 16th-19th century.. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870997831. (see index: p. 148-152; plate 25)

![Prince Aurangzeb riding against the maddened War elephant Sudhakar in the year 1633.[6]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2b/Prince_Awrangzeb_%28Aurangzeb%29_facing_a_maddened_elephant_named_Sudhakar_%287_June_1633%29.jpg/170px-Prince_Awrangzeb_%28Aurangzeb%29_facing_a_maddened_elephant_named_Sudhakar_%287_June_1633%29.jpg)

![Shah Jahan receiving Persian Safavid ambassador Ali Mardan Khan in the year 1638.[7][8]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d1/Shah_Jahan_Receives_Persian_Ambassadors.jpg/144px-Shah_Jahan_Receives_Persian_Ambassadors.jpg)