Hamburg Parliament

Hamburg Parliament Hamburgische Bürgerschaft | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Established | 1410 |

| Leadership | |

Carola Veit, SPD since 23 March 2011 | |

| Structure | |

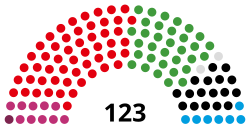

| Seats | 123 |

| |

Political groups | Government (86)

Opposition (37)

|

| Elections | |

Last election | 23 February 2020 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Hamburg Rathaus | |

| Website | |

| Hamburgische Bürgerschaft | |

The Hamburg Parliament (German: Hamburgische Bürgerschaft; literally “Hamburgish Citizenry”) is the unicameral legislature of the German state of Hamburg according to the constitution of Hamburg. As of 2020 there are 123 sitting members, representing 17 electoral districts.[1] The parliament is situated in the city hall Hamburg Rathaus and is part of the Government of Hamburg.

The parliament is among other things responsible for the law, the election of the Erster Bürgermeister (First Mayor) for the election period and the control of the Senate (cabinet).

The President of the Hamburg Parliament is the highest official person of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg.[2]

Its members are elected in universal, direct, free, equal and secret elections every five years.[3][4]

History

[edit]

|

|---|

Origins

[edit]Bürgerschaft (literally citizenry) is a term in use since the Middle Ages to refer to the male inhabitants of Hamburg with citizenship. A committee of the landowning class within the city, called Erbgesessene Bürgerschaft, was formed out of this group in the 15th century to consult with the city's ruling councillors (Ratsherren; later called the "Senate of Hamburg" following the Roman example), and to be consulted by them.

The city council, in early times supposedly elected by male citizens, had turned into an autocratic body restaffing its vacancies by coöptation. The system of coöptating seats was prone to corruption and it came to several major struggles in the following decades. The first relevant document organising power and tasks of citizenry and the city council (government), which was traditionally dominated by the local merchants, dates back to 1410 and is named Erster Rezess (roughly: The first Settlement, literally the agreement reached before parting [Lat. recedere] of the negotiating partners).[5]

The Erster Rezess came about after the city council (Senate, no parliament but the government) had cited and arrested Heyne Brandes,[6] a burgher of Hamburg. Brandes had claims due against John IV, Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg from a credit which Brandes had granted earlier. Brandes had taken the defaulting duke, during his visit in Hamburg in 1410, to task and dunned him in a way the duke considered insulting.[7] The duke complained to the senate, which then interrogated Brandes. He admitted the dunning, and thus the senate arrested him.[7] This caused a civic uproar of Hamburgers.

"In Hamburg as in other cities, the parishes ... had been not only church districts but also municipal political districts since the Middle Ages. They ... formed four incorporated bodies (Petri, Nikolai, Katharinen, Jacobi) in which the "allodial" (property-owning) burghers and the heads of guilds – thus only a fraction of the male population – were entitled to vote."[8] The enfranchised citizens, grouped along their parishes, then elected from each of the then four parishes 12 representatives (deacons), the Council of the Forty-Eighters (die Achtundvierziger), who on Saint Lawrence Day (August 10) stipulated with the senate the Recess of 1410 (later called Erster Rezess).

The Erster Rezess is now considered Hamburg's oldest constitutional act, establishing first principles balancing the power of the government of the city-state and its citizens. The Erster Rezess established the principle that in Hamburg nobody may be arrested at the government's will but only after a prior judicial hearing and conviction (except of in flagrante delicto).[9] Furthermore, the Erster Rezess stipulated that the council (senate) has to synchronise with the citizens in all severe matters, such as war, contracts with foreign powers, or decisions as to levying new or raising higher taxes, by convoking the citizens in plenary assembly.[10] The plenary assemblies met in front of the city hall. With an overall population of roughly 10,000 people and only a minority among the male adults enjoying citizenship, the plenary assemblies of the citizenry (the Bürgerschaft) formed a functioning body, though with restricted authority.

The Forty-Eighters persisted, serving as opinion-forming committee within the citizenry, and developed into the first permanent representation of the citizens of Hamburg.[9] Further settlements (Rezesse) between senate and Bürgerschaft constituted the more formalised coöperation between them. "The Reformation brought with it a significant curtailment of the senate's governmental power."[8] In Hamburg the Reformation started in 1524 and was adopted by the Senate in 1529, fixed by the Langer Rezess (roughly: Long Settlement, negotiated for more than a year). The Langer Rezess made the ruling council (senate) accountable to several civic committees, forming together the Erbgesessene Bürgerschaft.

"At about the same time, three deacons from each parish (twelve altogether), acting as "chief elders",[11] took on the task of centralizing, administering, and uniformly distributing relief to the poor."[8] The chief elders were also entitled to decide with the senate in all matters concerning the welfare and the concord of the city, and formed thus besides Bürgerschaft and senate the third constitutive body, however, excluded from government again by the new constitution of 1859.[12] The Forty-Eighters, now called Kollegium der Diakone (collegial panel of the deacons) continued to exist and the plenary assembly of citizens was replaced by the Assembly of the 144 (Hundertvierundvierziger, or formally: Kollegium der Diakone und Subdiakone), comprising 36 representatives (12 deacons and 24 subdeacons) from each parish.

Later the parishioners of St. Michael's Church in the New Town, established as parish independent of St. Nicholas in 1647, were granted the same rights as the burghers in one of the four parishes in the Old Town, and the same number of representatives. "Beginning in 1685, there were thus fifteen chief elders: sixty deacons instead of forty-eight and 180 assembly members altogether, rather than 144. These structures existed into the nineteenth century, with each college recruiting new members from the next larger."[8] This assembly of 180 (as of 1685) was more and more identified as the Erbgesessene Bürgerschaft, although the council of the Sixty (extended from the Forty-Eighters) was a panel previously subsumed as part of it.

Since Lutheran parishes and the collegial bodies staffed with their parishioners formed the constitutional bodies of Hamburg there was no easy way to open politics for non-Lutherans. Bürgerschaft, chief elders and senate could not settle all aspects of the sensitive balance of power. Thus, a commission, sent by the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, had to secure the peace by force in 1708 and the city was once more negotiating and reforming her own administrative structures in the following years.

The Vormärz led to even more criticism of the established structures and Hamburg participated in the elections of the Frankfurt Parliament in 1848. This resulted in even more debates and the Erbgesessene Bürgerschaft passed a new electoral law to meet the criticism in September 1848 but the restoration, supported and enforced by Prussian troops during the First Schleswig War, turned the table.

Elections of 1859

[edit]A new attempt to reform the constitution was launched after long discussions in 1859 and the Erbgesessene Bürgerschaft met for the last time in November of this year to establish a new order as well as to disband itself in favour of the Bürgerschaft. Since 1859 Bürgerschaft refers to this elected parliamentary body.

Hamburg parliament in the Federal Republic

[edit]The Social Democratic Party (SDP) maintained its influence over the city’s politics during the 1949 elections. Their victory was significant during a time of considerable reconstruction and reform in Germany. The SDP continued to govern Hamburg from that time forward, except from 1953 to 1957, when the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) was in power. After this period, however, the SDP regained control and developed Hamburg’s political, social, and economic faucets, stretching their influence late into the 20th century.[13]

Since March 23, 2011 the Hamburg Parliament has been in its 20th legislative period in the Federal Republic of Germany. A SPD-Government succeeded a coalition of CDU and the Greens.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2008) |

Organisation

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2009) |

President and board

[edit]The president of the parliament presides over the parliament and its sessions. The president is supported by a 'First Vice-president' and 3 vice presidents, all are elected by the representatives. President, vice presidents, and 3 recording clerks are the board (German: Präsidium).

The president of the Hamburg Parliament has been Carola Veit since 2011.

| Term | Name |

|---|---|

| 1859–1861 | Dr. Johannes Versmann |

| 1861–1863 | Dr. Isaac Wolffson |

| 1863–1865 | Dr. Hermann Baumeister |

| 1865–1868 | Dr. Georg Kunhardt |

| 1868–1868 | Dr. Hermann Baumeister |

| 1869–1869 | Johann A. T. Hoffmann |

| 1869–1877 | Dr. Hermann Baumeister |

| 1877–1885 | Dr. Gerhard Hachmann |

| 1885–1892 | Dr. Otto Mönckeberg |

| 1892–1902 | Siegmund Hinrichsen |

| 1902–1913 | Julius Engel |

| 1913–1919 | Dr. Alexander Schön |

| 1919–1920 | Berthold Grosse |

| 1920–1928 | Rudolf Ross |

| 1928–1931 | Max Hugo Leuteritz |

| 1931–1933 | Dr. Herbert Ruscheweyh |

| 1946 | Dr. Herbert Ruscheweyh |

| 1946–1960 | Adolph Schönfelder |

| 1960–1978 | Herbert Dau |

| 1978–1982 | Peter Schulz |

| 1982–1983 | Dr. Martin Willich |

| 1983–1986 | Peter Schulz |

| 1986–1987 | Dr. Martin Willich |

| 1987–1987 | Elisabeth Kiausch |

| 1987–1991 | Helga Elstner |

| 1991–1993 | Elisabeth Kiausch |

| 1993–2000 | Ute Pape |

| 2000–2004 | Dr. Dorothee Stapelfeldt |

| 2004–2010 | Berndt Röder |

| 2010–2011 | Lutz Mohaupt |

| 2011 | Dr. Dorothee Stapelfeldt |

| 2011–2024 | Carola Veit |

Council of Elders

[edit]The Council of Elders (German: Ältestenrat) consists of the president, the vice presidents and several members, appointed by the parliamentary groups. The council support the president and the board regarding decisions of the agenda, personnel matters, and financial affairs.

Parliamentary groups

[edit]Parliamentary groups (German: Fraktionen) are pooled by minimum 6 members of the parliament. Most these groups are by one party.

Committees

[edit]The daily work of the parliament is done in committees.

Candidates' qualifications

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2008) |

The qualification is regulated by law. As of 2008, candidate must be at least 18 years old, and must not be allowed to vote by a verdict, is patient of a psychiatric ward under law, or has a representative under law.[15]

Current composition

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (February 2015) |

References

[edit]- ^ "Members of Hamburg Parliament". Hamburgische Bürgerschaft. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ^ constitution of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, § 18

- ^ What is Hamburg Parliament?, Hamburgische Bürgerschaft, archived from the original on 2011-07-19, retrieved 2008-08-14

- ^ Who works in Parliament?, Hamburgische Bürgerschaft, archived from the original on 2007-08-13, retrieved 2008-08-14

- ^ The term Rezess, more precisely Hanserezess, was also used by the Hanseatic League for the final communiqués reached on its diets (Hansetage).

- ^ His Low Saxon name is today often quoted in the then unknown modern Standard German variant as Hein Brand(t).

- ^ a b Tim Albrecht and Stephan Michaelsen, Entwicklung des Hamburger Stadtrechts Archived 2013-12-21 at the Wayback Machine, note 36, retrieved on 14 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d Rainer Postel, "Hamburg at the Time of the Peace of Westphalia", in: 1648, War and Peace in Europe: 3 vols., Klaus Bussmann and Heinz Schilling (eds.), Münster in Westphalia: Veranstaltungsgesellschaft 350 Jahre Westfälischer Friede, 1998, (=Catalogue for the exhibition "1648: War and Peace in Europe" 24 October 1998-17 January 1999 in Münster in Westphalia and Osnabrück), vol. 1: 'Politics, Religion, Law, and Society', pp. 337–343, here p. 341. ISBN 3-88789-128-7.

- ^ a b Tim Albrecht and Stephan Michaelsen, Entwicklung des Hamburger Stadtrechts Archived 2013-12-21 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 14 May 2013.

- ^ Angelika Grönwall and Joachim Wege, Die Bürgerschaft. Geschichte, Aufgaben und Organe des Hamburger Landesparlaments, 3rd updated ed., Hamburg: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung, 1989, p. 7.

- ^ The Chief Elders of Hamburg (die Oberalten), supervised all religious endowments for the poor after the donations and revenues for the poor of all parishes were centralised in the central God's Chest (Gotteskasten). The then four parishes agreed to this centralisation stipulating in the Langer Rezess with the senate on 29 September 1528 that the college of the chief elders (Kollegium der Oberalten) will be in charge of the endowments. Until today this body administers the endowments taken over then and donated to Hamburg's Lutheran church since. Cf. Die Oberalten Archived 2013-06-20 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 21 January 2013.

- ^ Cf. Die Oberalten Archived 2013-06-20 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved on 21 January 2013.

- ^ "German Bundestag - German parliamentarism". German Bundestag. Retrieved 2024-10-16.

- ^ Hamburgische Bürgerschaft - Präsidenten der Bürgerschaft seit 1859 (in German), retrieved 2017-10-25

- ^ "Gesetz über die Wahl zur hamburgischen Bürgerschaft (BüWG) in der Fassung vom 22. Juli 1986" (in German). Archived from the original on 2005-01-08. Retrieved 2009-09-12.