Abd al-Hosayn Ayati

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: blockquotes that could be paraphrased, unclear table, works section needs to be reworked for legibility. (November 2023) |

Abd al Ḥosayn Ayati | |

|---|---|

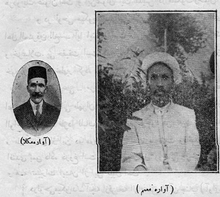

Abd al-Hosayn Ayati as a cleric (right) and as a Baháʼí (left) | |

| Born | 1871 Taft, Yazd, Sublime State of Persia |

| Died | 1953 (aged 81–82) Yazd, Imperial State of Iran |

| Occupation | Educator, missionary, poet |

| Subject | Islam, Baháʼí Faith |

Abd al Ḥosayn Ayati (1871—1953), known to Baháʼís as Avarih, was an Iranian convert to the Baháʼí Faith, who later converted back to Islam and wrote several polemic works against his former religion.[1] He is regarded in Baháʼí circles as an apostate.[1] In his later years he served as a secondary school teacher while writing poetry and history,[2][3] and was regarded as a competent orator.[4]

During his 18 years as a Baháʼí, Ayati was a missionary to Turkestan, the Caucasus, the Ottoman Empire, and Egypt.[1] During this time he associated with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and wrote a two-volume history of the Baháʼí Faith, al-Kawākeb al-dorrīya (1914), which was translated to Arabic in 1924.[1] His main polemic writing refuting the Baháʼí Faith was the three-volume Kašf al-ḥīal (1928-31).[1] He has a total of seventeen published titles on various subjects, such as the history of Yazd Ātaškada-ye yazdān (1928), and commentaries and translations of the Qur'an.[1]

Early life

[edit]Ayati was born in a religious family in the city of Taft in the province of Yazd, Iran in 1871. His father was a Mullah by the name of Mohammad-Taqi Akhund Tafti. Ayati received a religious education from childhood.[5][2] At the age of 15 he moved to Yazd where he studied at the Khan religious school for two years in Islamic subjects. He then moved to Iraq to study at the seminaries in Najaf and Karbala where he became a student of Ayatollah Mirza Hasan Shirazi. This only lasted for a few months and he was forced to return to Yazd after receiving the news of the death of his father.[3]

Ayati became a cleric in his youth while at Yazd and would give sermons and lead prayers. He showed great interest in literature and poetry.[5][2] According to one of his brief autobiographies, he hadn't reached puberty yet when he was allowed to wear the classic Muslim cleric clothing and give sermons. At the age of twenty, he lost his father and at the age of twenty five, he was stationed as the Imam of the Mosque where his late father led prayers.[4]

He became a Baháʼí at the age of 30.[5][2] This is how Ayati describes it:

"I became familiar with the Baháʼís at the age of 30 and left my beloved homeland. I removed the Turban from my head and shaved my beard and started traveling around the world."[3]

Life as a Bahá'í

[edit]

After becoming a Baháʼí, Ayati started a career as a Baháʼí missionary that saw him traveling to Tehran, the Iranian capital and from there to many Iranian cities and provinces.[3] His Missionary travels then took him outside of Iran and in a span of 18 years he traveled to Turkestan, the Caucasus, the Ottoman Empire, and Egypt. Due to his numerous endeavors 'Abdu'l Baha gave him the titles of "Raʾīs al-Moballeḡīn" (Chief of Missionaries) and "Avarih" (Wanderer).[1]

In 1923, Shoghi Effendi sent Ayati to England to teach the Baháʼí Faith. This was first announced to the Baháʼís of the west through the Baháʼí Magazine, Star of the West.[6] In a letter addressed to the Baha'is in Britain Shoghi describes Ayati and his book al-Kawakib al-durriya in this manner:

"Ere long, an able and experienced teacher recently arrived from Persia will visit your shores, and will, I trust, by his thorough knowledge of the Cause, his wide experience, his fluency, his ardor, and his devotion, reanimate every drooping spirit, and inspire the active worker to make fresh and determined efforts for the deepening as well as the spreading of the movement, in those regions."[7]

The Former member of the Universal House of Justice, Luṭfu'lláh Ḥakím, served as his translator during this visit.[8] Subsequent issues of Star of the West chronicled Avarih's Journey and activities while in England according to the following Table:

| Year | Volume | No. | Pages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1923 | 14 | 1 | 20-22 |

| 1923 | 14 | 2 | 57 |

| 1923 | 14 | 3 | 91-93 |

| 1923 | 14 | 4 | 120 |

| 1923 | 14 | 5 | 136 |

Ayati then left England for Cairo to print his two volume work on the history of the Baháʼí faith called al-Kawakib al-durriya. According to Shoghi Effendi this work was "the most comprehensive and reliable history of the Movement yet published"[9] and " the most graphic, the most reliable and comprehensive of its kind in Bahai literature"[7] and was labelled as the "great history of the Baháʼí cause" by the Baháʼí magazine, Star of the West.[10] According to Encyclopaedia Iranica it "is still one of the major works on the subject."[1]

In a letter addressed to the Baháʼís of some European countries, Shoghi Effendi writes about Avarih, thus:

His wide experience and familiarity with the various aspects of the Movement, his profound and extensive knowledge of its history; his association with some of the early believers, the pioneers and martyrs of the Cause will I am sure to appeal to every one of you and will serve to acquaint you still further with the more intimate and tragic side of this remarkable Movement.[11]

Avarih also produced a detailed account of the safekeeping and transportation of the remains of the Báb in his book, al-Kawakib al-durriya.[12]

After reverting to Islam he openly opposed the Baháʼí Faith and was considered a Covenant-breaker. He was labelled by Shoghi Effendi as a "shameless apostate".[13]

The references made to Avarih in John Esslemont's book Baháʼu'lláh and the New Era were removed in subsequent editions published after Avarih's apostasy from the Baháʼí Faith.[14]

Life after reverting to Islam

[edit]He returned to Iran and spent the rest of his life as a secondary school teacher.[1] For the first ten years he taught literature at the Sultaniyya, Elmieh, Razi, and Dar al-Funun schools in Tehran. He was then transferred to Yazd and continued his teaching career.[3]

Ayati passed away in the City of Yazd in 1953.[4] The cause of death was an illness that he was afflicted with during a trip to Tehran shortly before his death. His body was transferred to Qum and he was buried there. Shoghi Effendi describes Avarih's death as a strike of God's avenging hand in the following manner:

"Following the successive blows which fell with dramatic swiftness two years ago upon the ring-leaders of the fast dwindling band of old Covenant-breakers at the World Center of the Faith, God's avenging hand struck down in the last two months, Avarih, Fareed and Falah, within the cradle of the Faith, North America and Turkey, who demonstrated varying degrees, in the course of over thirty years, of faithlessness to 'Abdu'l-Bahá. The first of the above named will be condemned by posterity as being the most shameless, vicious, relentless apostate in the annals of the Faith, who, through ceaseless vitriolic attacks in recorded voluminous writings and close alliance with its traditional enemies, assiduously schemed to blacken its name and subvert the foundations of its institutions."[15]

Works

[edit]

Ayati's works are mainly focused on history, literature and poetry, Islamic religious topics, and refuting Baha'is. According to Ayati his Persian and Arabic poems amounted to about 30,000 lines.[4]

The following is a list of some works by Ayati in alphabetical order:

- َAl-Kawākeb al-dorrīya fī maʾāṯer al-bahāʾīya (Shining Stars of Baháʼí Remnants): a work on history of the Baháʼí Faith.[16]

- Asha'yi Hayat (The Rays of Life): A collection of poems that he composed at the age of eighty (Yazd: 1949)[17]

- Atashkadeh Yazdan (God's Fireplace): A book on the history of the city of Yazd in Iran.[18]

- Chakame shamshir (Ode of the Sword): A poetry collection.[17]

- Farhang-i Ayati (Ayati's Dictionary): A Persian-Arabic dictionary.[19]

- Goftare Ayati (Ayaty's statements): Printed in Tehran (1929).[17]

- Heralds of the New Day: Adapted from addresses given in London by Jináb-i-Avárih.[20]

- Hogoye Irani (The Persian Hugo): Printed in Yazd (1942).[17]

- Insha `alee (Good writing): Printed in Tabriz (1932).[17]

- Kašf al-ḥīal (Uncovering the Deceptions): His work in three volumes in refutation of the Baháʼí Faith.[1] Vol. 1, Vol. 2, vol. 3.

- Kherad name (A letter of Wisdom): A collection of romantic poems printed in Istanbul.[4][17]

- Kitabi Nubi (Nubi's Book): A translation of the Quran in 3 volumes printed in Yazd (1945-1947).[17]

- Maliki aql wa efrit jahl (The Angel of Intellect and the Monster of Ignorance): Printed in Tehran (1933).[17]

- Moballighe Baha'i dar mahzar-e ayatollah shaykh mohammad khalesi zadeh (A Baha'i Missionary in the Presence of Shaykh Muhammad Khalesi Zadeh): The report of Iranian Army personnel from Yazd that were proselytized by a Baha'i missionary and decided to consult Ayatollah Khalesizadeh about the Missionaries claims.[21]

- Naghmeye del (Melody of the Heart): A poetry collection.[17]

- Namakdan (Saltshaker): A literature magazine published from 1925-1935 in four issues.[5]

- Qasideye Quraniyeh (The Quranic Poem): A collection of poetry printed in Tehran.[17]

- Rawish-e negaresh-e farsi (How to write in Persian): A guide on writing in Persian printed in Tehran.[17]

- Siyahat nam-i doctor jack amricaiee (The travel diary of Dr. Jack, the American): Real life accounts narrated as a story about the life of a foreigner investigating the Baháʼí claims during his travels that Ayati refers to using the pseudonym, Jack the American.[22]

- Tarikh mukhtasar-e falsafe (A Brief History of Philosophy): Printed in Tehran (1933)[17]

- Tafsir quran (An exegesis on the Quran): In three volumes.[4]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Afshar 2011.

- ^ a b c d Khalkhali 1958.

- ^ a b c d e Rastegar 1978.

- ^ a b c d e f Burqaie 1994.

- ^ a b c d Narges 2009.

- ^ "Jenabe Avareh in England" (PDF). Start of the West. 13: 345. 1923.

- ^ a b "A Letter to the Friends in Great Britain" (PDF). Star of the West. 13: 329. 1923.

- ^ "Star of the West/Volume 14/Issue 1/Text - Bahaiworks, a library of works about the Bahá'í Faith". bahai.works. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ "New Books" (PDF). Star of the West. 14: 93. 1923.

- ^ "Heralds of the New Day" (PDF). Start of the West. 14: 269. 1923.

- ^ "Bahá'í Reference Library - The Light of Divine Guidance (Volume 2), Page 6". reference.bahai.org. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- ^ "Efforts to preserve the remains of the Bab". bahai-library.com. Retrieved 2021-04-06.

- ^ Maxwell, Ruhiyyih (Mary Khanum) (1969). The Priceless Pearl. London: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 120.

- ^ Salisbury, Vance (1997). "A Critical Examination of 20th-Century Baha'i Literature". Baháʼí Library Online. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ Effendi, Shoghi (1971). Messages to the Baha'i World (1950 - 1957). US: Bahá’í Publishing. p. 53.

- ^ Ayati 1914.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l آیتی [Ayati]. The Center for the Great Islamic Encyclopedia.

- ^ Ayati, Abd al-Husayn (1938). آتشکده یزدان.

- ^ Ayati, Abd al-Husayn (1935). فرهنگ آیتی. Tehran: Matba Danesh.

- ^ "Star of the West/Volume 14/Issue 9/Text - Bahaiworks, a library of works about the Bahá'í Faith". bahai.works. Retrieved 2021-01-03.

- ^ Ayati, Abd al-Husayn (1987). مبلغ بهایی در محضر آیت الله خالصی زاده (PDF). Yazd, Iran: Golbahar.

- ^ Ayati, Abd al-Husayn (1927). سیاحت نامه دکتر ژاک آمریکایی (PDF). Tehran: Khavar.

References

[edit]- Afshar, Iraj (2011-08-18). "ĀYATĪ, ʿABD-AL-ḤOSAYN". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Ayati, Abd al-Husayn (1914) [Arabic tr. published 1924, Digitally republished 1999 by H-Net]. Al-Kawakib ad-Durriyyah [Brilliant Stars] (in Persian). Vol. 1. Cairo, Egypt: Matba`at as-Sa`adah.

- Burqaie, Sayyed Muhammad Baqir (1994). سخنوران نامی عاصر ایران (PDF). Vol. 1. Qum: Khorram. p. 134.

- Khalkhali, Sayyed Abd al-hamid (1958). تذکره شعرای معاصر ایران (PDF). Vol. 2. Tehran: Rangin. pp. 1–6.

- Narges, Dehghanian (2009). نمکدان دفتر ادبیات شعر و نغز دوره اول پهلوی (PDF). Payame Baharestan. 1388 (3): 473–478.

- Rastegar, Sayyed Mahmoud (1978). احوال و آثاز عبدالحسین آیتی یزدی [The life and works of Abd al-Husayn Ayati Yazdi]. Wahid. 242: 29–34.