Autonomous agency theory

Autonomous agency theory (AAT) is a viable system theory (VST) which models autonomous social complex adaptive systems. It can be used to model the relationship between an agency and its environment(s), and these may include other interactive agencies. The nature of that interaction is determined by both the agency's external and internal attributes and constraints. Internal attributes may include immanent dynamic "self" processes that drive agency change.

History

[edit]Stafford Beer coined the term viable systems in the 1950s, and developed it within his management cybernetics theories. He designed his viable system model as a diagnostic tool for organisational pathologies (conditions of social ill-health). This model involves a system concerned with operations and their direct management, and a meta-system that "observes" the system and controls it. Beer's work refers to Maturana's concept of autopoiesis,[1] which explains why living systems actually live. However, Beer did not make general use of the concept in his modelling process.

In the 1980s Eric Schwarz developed an alternative model from the principles of complexity science. This not only embraces the ideas of autopoiesis (self-production), but also autogenesis (self-creation) which responds to a proposition that living systems also need to learn to maintain their viability. Self-production and self-creation are both networks of processes that connect an operational system of agency structure from which behaviour arises, an observing relational meta-system, this itself observed by an "existential" meta-meta-system. As such Schwarz' VST constitutes a different paradigm from that of Beer.

AAT is a development of Schwarz' paradigm through the addition of propositions setting it in a knowledge context.[2]

Development

[edit]AAT is a generic modelling approach that has the capacity to anticipate future potentials for behaviour. Such anticipation occurs because behaviour in the agency as a living system is "structure determined",[3] where the structure itself of the agency is responsible for that anticipation. This is like anticipating the behaviour of both a tiger or a giraffe when faced with food options. The tiger has a structure that allows it to have speed, strength and sharp inbuilt weapons to kill moving prey, but the giraffe has a structure that allows it to acquire its food in high places in a way the tiger could not duplicate. Even if a giraffe has the speed to chase prey, it does not have the resources to kill and eat it. Agency generic structure is a substructure defined by three systems that are, in general terms, referred to as:

- existential (pattern of thematic relevance that is the consequence of experience);

- noumenal (representing the nature of a phenomenal effect subjectively through conceptual relationships)

- phenomenal (maintaining patterns of context related structural relevance connected with action, and constituting an origin for experience).

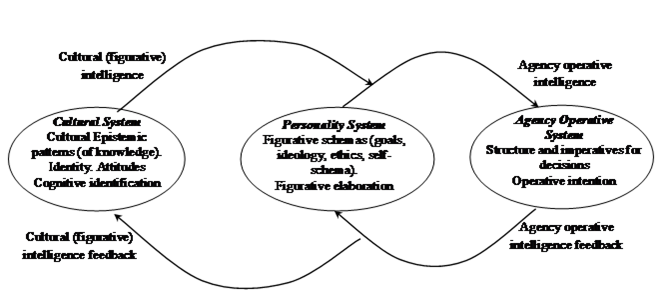

These generic systems are ontologically distinct; their natures being determined by the context in which the autonomous agency exists. The substructure also maintains a superstructure that is constructed through context related propositional theory. Superstructural theory may include attributes of collective identity, cognition, emotion, personality; purpose and intention; self-reference, self-awareness, self-reflection, self-regulation and self-organisation. The substructural systems are connected by autopoietic and autogenetic networks of processes as shown in Figure 1 below.

The terminology becomes simplified when the existential system is taken to be culture, and it is recognised that Piaget's[4] concept of operative intelligence is equivalent to autopoiesis, and his figurative intelligence to autogenesis. The noumenal system now becomes a personality system, and autonomous agency theory now becomes cultural agency theory (CAT).[5] This is normally used to model plural situations like organisations or a nation states, when its personality system is taken to have normative characteristics (see also Normative personality),[6][7] that is, driven by cultural norms as represented in Figure 2 below. This has developed further through mindset agency theory[8] enabling agency behaviour to be anticipated.[9]

A feature of this modelling approach is that the properties of the cultural system act as an attractor for the agency as a whole, providing constraint for the properties of its personality and operative systems. This attraction ceases with cultural instability, when CAT reduces to instrumentality with no capacity to learn. Another feature is driven by possibilities of recursion permitted using Beer's proposition of viability law: every viable system contains and is contained in a viable system.[10]

Cultural agency theory

[edit]Cultural agency theory (CAT) as a development of AAT.[11] It is principally used to model organisational contexts that have at least potentially stable cultures. The existential system of AAT becomes the cultural system, the figurative system become a normative personality,[12] and the operative system now represents the organisational structure that facilitates and constrains behaviour.

The cultural system may be regarded as a (second-order) "observer" of the instrumental couple that occurs between the normative personality and the operative system. The function of this couple is to manifest figurative attributes of the personality, like goals or ideology, operatively consequently influencing behaviour. This instrumental nature occurs through feedforward processes such that personality attributes can be processed for operative action. Where there are issues in doing this, feedback processes create imperatives for adjustment. This is like having a goal, and finding that it cannot be implemented, thereby having to reconsider the goal. This instrumental couple can also be seen in terms of the operative system and its first-order "observing" system, the normative personality. So, while personality is a first-order "observer" of CAT's operative system, it is ultimately directed by its second-order cultural "observer" system.

A development of this has occurred using trait theory from psychology. Unlike other trait theories of personality, this adopts epistemic traits[13] that centres on values, an approach that tends to be more stable (since basic values tend to be stable) in terms of personality testing and retesting, than other approaches that use (for instance) agency preferences (like Myers-Briggs Type Indicator) that may change between test and retest. This trait theory for the normative personality is called mindset agency theory,[14] and is a development of Maruyama's Mindscape Theory.[15]

The cognitive process by which personality is represented through epistemic trait functions (called types), can be explained through both instrumental and epistemic rationality,[citation needed] where instrumental rationality (also referred to as utilitarian,[16] and related to the expectations about the behaviour of other human beings or objects in the environment given some cognitive basis for those expectation) is independent of, if constrained by, epistemic rationality (related to the formation of beliefs in an unbiased manner, normally set in terms of believable propositions: due to their being strongly supported by evidence, as opposed to being agnostic towards propositions that are unsupported by "sufficient" evidence, whatever this means). Applications of CAT could be found in social, political and economical sciences, for instance recend studies analyzed Donald Trump and Theresa May personalities.

Higher orders of autonomous agency

[edit]Stafford Beer's (1979) viable system model is a well-known diagnostic model that comes out of his management cybernetics paradigm. Related to this is the idea of first-order and second-order cybernetics. Cybernetics is concerned with feedforward and feedback processes, and first-order cybernetics is concerned with this relationship between the system and its environment. Second-order cybernetics is concerned with the relationship between the system and its internal meta-system (that some refer to as "the observer" of the system). Von Foerster[17] has referred to second-order cybernetics as the "cybernetics of cybernetics". While attempts to explore higher orders of cybernetics have been made,[18] no development into a general theory of higher cybernetic orders has emerged from this paradigm. In contrast, extending the principles of autonomous agency theory, a generic model has been formulated for the generation of higher cybernetic orders,[19] developed using the concepts of recursion and incursion as proposed by Dubois.[20][21] The model is reflective, for instance, of processes of knowledge creation for community learning[22] and symbolic convergence theory.[23] This nth-order theory of cybernetics links with "the cybernetics of cybernetics" by assigning to its second-order cybernetic concept inferences that may arise from any higher-order cybernetics that may exist, if unperceived. The network of processes in this general representation of higher cybernetic orders is expressed in terms of orders of autopoiesis, so that for instance autogenesis may be seen as a second-order of autopoiesis.

See also

[edit]- Agency (philosophy)

- Autogenesis, a thermodynamic synergy in living systems

- Cybernetics

- Second-order cybernetics

References

[edit]- ^ Maturana H.R., Varela F.J (1979). Autopoiesis and Cognition. Boston: Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science

- ^ Yolles, M.I., 2006, Organizations as Complex Systems: an introduction to knowledge cybernetics, Information Age Publishing, Inc., Greenwich, CT, USA

- ^ Maturana, H.R., 1988, Reality: the search for objectivity or the Quest for a compelling argument. Irish J. Psych. 9:25-82

- ^ Piaget, J. (1950). The Psychology of Intelligence, Harcourt and Brace, New York

- ^ G.A.N.D. blog http://blog.gand.biz/2016/10/cultural-agency-theory-autonomous-agency-theory/ Archived 2016-10-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yolles, M.I., Fink, G., Frieden, R. (2012). Organisations as Emergent Normative Personalities: part 2, predicting the unpredictable, Kybernetes, 41(7/8)1014-1050)

- ^ Fink, G. Yolles, M. (2014) The Affective Agency: An Agency with Feelings and Emotions, http://ssrn.com/abstract=2463283

- ^ Yolles, M.I.; Fink, G. (2014). "Personality, pathology and mindsets: part 1 – Agency, Personality and Mindscapes". Kybernetes. 43 (1): 92–112. doi:10.1108/k-01-2013-0011.

- ^ Yolles, M.I, Fink, G. (2014). Personality, pathology and mindsets: part 1 – Agency, Personality and Mindscapes, Kybernetes, 43(1) 92-112

- ^ Beer, S., (1959), Cybernetics and Management, English U. Press, London.

- ^ Gua, K.; Yolles, M.; Fink, G.; Iles, P. (2016). The Changing Organisation: Agency Theory in a Cross-cultural Context. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Yolles, M. (2009). "Migrating Personality Theories Part 1: Creating Agentic Trait Psychology?". Kybernetes. 38 (6): 897–924. doi:10.1108/03684920910973153. S2CID 16190785.

- ^ Yolles, M.; Fink, G. "An Introduction to Mindset Agency Theory". ResearchGate. Organisational Coherence and Trajectory Project. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ Gua, K.; Yolles, M.; Fink, G.; Iles, P. (2016). The Changing Organisation: Agency Theory in a Cross-cultural Context. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Mauyama, M. (1980). "Mindscapes and Science Theories" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 21 (5): 589–608. doi:10.1086/202539. S2CID 147362112. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ Von Glasersfeld, Ernest. "Aspects of Radical Constructivism" (PDF). Radical Constructivism. University of Vienna, Austria. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ Von Foerster, H (1975). The Cybernetics of Cybernetics, Biological Computer Laboratory, Champaign/Urbana, republished (1995), Future Systems Inc., Minneaopolis, MN

- ^ Boxer, P.J., Cohen, B. (2000). Doing time: the emergence of irreversibility, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 901(1):13–25

- ^ Yolles, M.I, Fink, G., 2015, A general theory of generic modelling and paradigm shifts: part 2 - cybernetic orders, Kybernetes, 44(2)299-310

- ^ Dubois D. M. (1996), Introduction to the Symposium on General Methods for Modelling and Control, Proceedings of the 14th International Congress on Cybernetics, Namur, 1995, Published by the International Association of Cybernetics, pp. 383-388)

- ^ Dubois, D, 2000, Review of Incursive Hyperincursive and Anticipatory Systems - Foundation of Anticipation in Electromagnetism, CASYS'99 - Third International Conference. Edited by Dubois, D.M. Published by The American Institute of Physics, AIP Conference Proceedings 517, pp3-30

- ^ Conceição, S.C., Baldor, M.J., Desnoyers, C.A. (2009). Factors Influencing Individual Construction of Knowledge in an Online Community of Learning and Inquiry Using Concept Maps. Lupion Torres, P (Ed.) Handbook of Research on Collaborative Learning Using Concept Mapping (pp.100-117). Information Science Reference: Hershey, NY.

- ^ Bormann, E. G. (1996). Symbolic convergence theory and communication in group decision making. In Hirokawa, RY, Scott Poole, M (Ed.), Communication and group decision making, Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA. pp. 2, 81-113