Data structure

In computer science, a data structure is a data organization and storage format that is usually chosen for efficient access to data.[1][2][3] More precisely, a data structure is a collection of data values, the relationships among them, and the functions or operations that can be applied to the data,[4] i.e., it is an algebraic structure about data.

Usage

[edit]Data structures serve as the basis for abstract data types (ADT). The ADT defines the logical form of the data type. The data structure implements the physical form of the data type.[5]

Different types of data structures are suited to different kinds of applications, and some are highly specialized to specific tasks. For example, relational databases commonly use B-tree indexes for data retrieval,[6] while compiler implementations usually use hash tables to look up identifiers.[7]

Data structures provide a means to manage large amounts of data efficiently for uses such as large databases and internet indexing services. Usually, efficient data structures are key to designing efficient algorithms. Some formal design methods and programming languages emphasize data structures, rather than algorithms, as the key organizing factor in software design. Data structures can be used to organize the storage and retrieval of information stored in both main memory and secondary memory.[8]

Implementation

[edit]Data structures can be implemented using a variety of programming languages and techniques, but they all share the common goal of efficiently organizing and storing data.[9] Data structures are generally based on the ability of a computer to fetch and store data at any place in its memory, specified by a pointer—a bit string, representing a memory address, that can be itself stored in memory and manipulated by the program. Thus, the array and record data structures are based on computing the addresses of data items with arithmetic operations, while the linked data structures are based on storing addresses of data items within the structure itself. This approach to data structuring has profound implications for the efficiency and scalability of algorithms. For instance, the contiguous memory allocation in arrays facilitates rapid access and modification operations, leading to optimized performance in sequential data processing scenarios.[10]

The implementation of a data structure usually requires writing a set of procedures that create and manipulate instances of that structure. The efficiency of a data structure cannot be analyzed separately from those operations. This observation motivates the theoretical concept of an abstract data type, a data structure that is defined indirectly by the operations that may be performed on it, and the mathematical properties of those operations (including their space and time cost).[11]

Examples

[edit]

There are numerous types of data structures, generally built upon simpler primitive data types. Well known examples are:[12]

- An array is a number of elements in a specific order, typically all of the same type (depending on the language, individual elements may either all be forced to be the same type, or may be of almost any type). Elements are accessed using an integer index to specify which element is required. Typical implementations allocate contiguous memory words for the elements of arrays (but this is not always a necessity). Arrays may be fixed-length or resizable.

- A linked list (also just called list) is a linear collection of data elements of any type, called nodes, where each node has itself a value, and points to the next node in the linked list. The principal advantage of a linked list over an array is that values can always be efficiently inserted and removed without relocating the rest of the list. Certain other operations, such as random access to a certain element, are however slower on lists than on arrays.

- A record (also called tuple or struct) is an aggregate data structure. A record is a value that contains other values, typically in fixed number and sequence and typically indexed by names. The elements of records are usually called fields or members. In the context of object-oriented programming, records are known as plain old data structures to distinguish them from objects.[13]

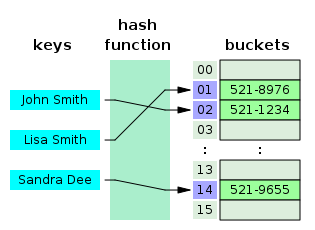

- Hash tables, also known as hash maps, are data structures that provide fast retrieval of values based on keys. They use a hashing function to map keys to indexes in an array, allowing for constant-time access in the average case. Hash tables are commonly used in dictionaries, caches, and database indexing. However, hash collisions can occur, which can impact their performance. Techniques like chaining and open addressing are employed to handle collisions.

- Graphs are collections of nodes connected by edges, representing relationships between entities. Graphs can be used to model social networks, computer networks, and transportation networks, among other things. They consist of vertices (nodes) and edges (connections between nodes). Graphs can be directed or undirected, and they can have cycles or be acyclic. Graph traversal algorithms include breadth-first search and depth-first search.

- Stacks and queues are abstract data types that can be implemented using arrays or linked lists. A stack has two primary operations: push (adds an element to the top of the stack) and pop (removes the topmost element from the stack), that follow the Last In, First Out (LIFO) principle. Queues have two main operations: enqueue (adds an element to the rear of the queue) and dequeue (removes an element from the front of the queue) that follow the First In, First Out (FIFO) principle.

- Trees represent a hierarchical organization of elements. A tree consists of nodes connected by edges, with one node being the root and all other nodes forming subtrees. Trees are widely used in various algorithms and data storage scenarios. Binary trees (particularly heaps), AVL trees, and B-trees are some popular types of trees. They enable efficient and optimal searching, sorting, and hierarchical representation of data.

A trie, or prefix tree, is a special type of tree used to efficiently retrieve strings. In a trie, each node represents a character of a string, and the edges between nodes represent the characters that connect them. This structure is especially useful for tasks like autocomplete, spell-checking, and creating dictionaries. Tries allow for quick searches and operations based on string prefixes.

Language support

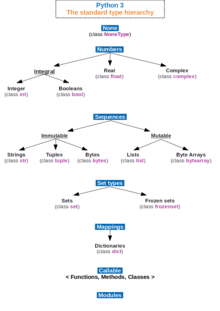

[edit]Most assembly languages and some low-level languages, such as BCPL (Basic Combined Programming Language), lack built-in support for data structures. On the other hand, many high-level programming languages and some higher-level assembly languages, such as MASM, have special syntax or other built-in support for certain data structures, such as records and arrays. For example, the C (a direct descendant of BCPL) and Pascal languages support structs and records, respectively, in addition to vectors (one-dimensional arrays) and multi-dimensional arrays.[14][15]

Most programming languages feature some sort of library mechanism that allows data structure implementations to be reused by different programs. Modern languages usually come with standard libraries that implement the most common data structures. Examples are the C++ Standard Template Library, the Java Collections Framework, and the Microsoft .NET Framework.

Modern languages also generally support modular programming, the separation between the interface of a library module and its implementation. Some provide opaque data types that allow clients to hide implementation details. Object-oriented programming languages, such as C++, Java, and Smalltalk, typically use classes for this purpose.

Many known data structures have concurrent versions which allow multiple computing threads to access a single concrete instance of a data structure simultaneously.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2009). Introduction to Algorithms, Third Edition (3rd ed.). The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262033848.

- ^ Black, Paul E. (15 December 2004). "data structure". In Pieterse, Vreda; Black, Paul E. (eds.). Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures [online]. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- ^ "Data structure". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 17 April 2017. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- ^ Wegner, Peter; Reilly, Edwin D. (2003-08-29). Encyclopedia of Computer Science. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 507–512. ISBN 978-0470864128.

- ^ "Abstract Data Types". Virginia Tech - CS3 Data Structures & Algorithms. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2023-02-15.

- ^ Gavin Powell (2006). "Chapter 8: Building Fast-Performing Database Models". Beginning Database Design. Wrox Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7645-7490-0. Archived from the original on 2007-08-18.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "1.5 Applications of a Hash Table". University of Regina - CS210 Lab: Hash Table. Archived from the original on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ^ "When data is too big to fit into the main memory". Indiana University Bloomington - Data Structures (C343/A594). 2014. Archived from the original on 2018-04-10.

- ^ Vaishnavi, Gunjal; Shraddha, Gavane; Yogeshwari, Joshi (2021-06-21). "Survey Paper on Fine-Grained Facial Expression Recognition using Machine Learning" (PDF). International Journal of Computer Applications. 183 (11): 47–49. doi:10.5120/ijca2021921427.

- ^ Nievergelt, Jürg; Widmayer, Peter (2000-01-01), Sack, J. -R.; Urrutia, J. (eds.), "Chapter 17 - Spatial Data Structures: Concepts and Design Choices", Handbook of Computational Geometry, Amsterdam: North-Holland, pp. 725–764, ISBN 978-0-444-82537-7, retrieved 2023-11-12

- ^ Dubey, R. C. (2014). Advanced biotechnology : For B Sc and M Sc students of biotechnology and other biological sciences. New Delhi: S Chand. ISBN 978-81-219-4290-4. OCLC 883695533.

- ^ Seymour, Lipschutz (2014). Data structures (Revised first ed.). New Delhi, India: McGraw Hill Education. ISBN 9781259029967. OCLC 927793728.

- ^ Walter E. Brown (September 29, 1999). "C++ Language Note: POD Types". Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2016-12-03. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ "The GNU C Manual". Free Software Foundation. Retrieved 2014-10-15.

- ^ Van Canneyt, Michaël (September 2017). "Free Pascal: Reference Guide". Free Pascal.

- ^ Mark Moir and Nir Shavit. "Concurrent Data Structures" (PDF). cs.tau.ac.il. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-01.

Bibliography

[edit]- Peter Brass, Advanced Data Structures, Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0521880374

- Donald Knuth, The Art of Computer Programming, vol. 1. Addison-Wesley, 3rd edition, 1997, ISBN 978-0201896831

- Dinesh Mehta and Sartaj Sahni, Handbook of Data Structures and Applications, Chapman and Hall/CRC Press, 2004, ISBN 1584884355

- Niklaus Wirth, Algorithms and Data Structures, Prentice Hall, 1985, ISBN 978-0130220059

Further reading

[edit]- Alfred Aho, John Hopcroft, and Jeffrey Ullman, Data Structures and Algorithms, Addison-Wesley, 1983, ISBN 0-201-00023-7

- G. H. Gonnet and R. Baeza-Yates, Handbook of Algorithms and Data Structures - in Pascal and C, second edition, Addison-Wesley, 1991, ISBN 0-201-41607-7

- Ellis Horowitz and Sartaj Sahni, Fundamentals of Data Structures in Pascal, Computer Science Press, 1984, ISBN 0-914894-94-3