Haliotis asinina

| Haliotis asinina Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A living specimen of Haliotis asinina | |

| |

| Five views of a shell | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Subclass: | Vetigastropoda |

| Order: | Lepetellida |

| Family: | Haliotidae |

| Genus: | Haliotis |

| Species: | H. asinina

|

| Binomial name | |

| Haliotis asinina | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

Haliotis asinum Donovan, 1808 | |

Haliotis asinina, common name the ass's-ear abalone, is a fairly large species of sea snail, a tropical gastropod mollusk in the family Haliotidae, the abalones, also known as ormers or pāua. Both the common name and the scientific name are based on the shape of the shell, which is long, narrow and curved, resembling the shape of a donkey's ear.

Shell description

[edit]The maximum shell length of this species is up to 120 mm (4+3⁄4 in),[3][4] but it more commonly grows up to about 90 mm (3+1⁄2 in).[4] The shell of Haliotis asinina has a distinctly elongated contour, in clear resemblance to a donkey ear, hence the common name. Its outer surface is smooth and almost totally covered by the mantle in life, making encrustations of other animals (such as barnacles) quite uncommon in comparison to other abalones.[4] The shell of H. asinina presents 5 to 7 ovate open holes on the left side of the body whorl. These holes collectively make up what is known as the selenizone which form as the shell grows. Its spire is somewhat conspicuous, with a mostly posterior apex. The color may variate between green olive or brown externally, with distinct roughly triangular patches. As is the case in many other abalones, the interior surface of the shell is strongly iridescent, with shades of pink and green.[4]

Distribution

[edit]This is an Indo-West Pacific species (Eastern Indian Ocean to the Central Pacific). It is common in the Andaman Islands and Nicobar Islands, Pacific islands, southern Japan and Australia (Northern Territory, Queensland, Western Australia).[4]

Ecology

[edit]Habitat

[edit]This abalone dwells in shallow water coral reef areas of the intertidal and sublittoral zones, commonly reaching a depth around 10 m (33 ft).[3][4] Though this species is quite abundant, aggregates of H. asinina are considered to be uncommon.[4]

Feeding habits

[edit]These large animals are nocturnal. They graze amongst turf algae and inhabit the undersides of boulders and coral bommies.[5]

Life cycle

[edit]Several major transitions in shell pattern and morphology can be observed during the life of Haliotis asinina. The species has a pelagobenthic life cycle that includes a minimal period of three to four days in the plankton. Biomineralisation begins shortly after hatching, with the fabrication of the larval shell (protoconch) over about a 10-hour period. The initial differentiation of biomineralising cells is likely to include a localised thickening of the dorsal ectoderm followed by an invagination of cells to form the shell gland. The shell gland then evaginates to form the shell field which expands through mitotic divisions to direct the precipitation of calcium carbonate (CaCO

3) via the secretion of organic molecules. In this way the larval shell (protoconch) is formed. The construction of the haliotid protoconch is complete following torsion. These structures allow the veliger larva to completely retract into a protective environment and rapidly fall out of the water column.[5]

-

Trochophore of Haliotis asinina 11 hours post-fertilisation, with a calcified protoconch (pc)

-

Protoconch

The next phase of biomineralisation does not commence until the competent veliger larva contacts an environmental cue that induces metamorphosis. The protoconch remains developmentally inert until the animal contacts a specific cue that initiates the process of metamorphosis.[5]

The postlarval shell (teleoconch) is laid down rapidly following metamorphosis with marked variation in the rate of its production between individuals. The transition from protoconch to teleoconch (juvenile/adult shell) is clearly visible at metamorphosis, and suggests the action of a different biomineralising secretome. The early postlarval shell is more robust and opaque than the larval shell but has no pigmentation. While the initial teloconch is not pigmented, it is textured and opaque such that postlarval shell growth is easily discerned from the larval shell.[5]

-

SEM image of initial postlarval shell at metamorphosis. The white arrow indicates the metamorphosis from the larval shell (protoconch) to juvenile shell.

-

A photograph of two postlarvae on a coralline algal surface.

The juvenile Haliotis asinina teloconch rapidly develops a uniform maroon colouration several weeks after metamorphosis, similar to the crustose coralline algae (CCA) that the larva has settled upon. At about 1 mm (39 mils) in size, further changes in the morphogenetic program of the mantle are reflected in the shell. Structurally, a pronounced series of ridges and valleys and a line of respiratory pores (tremata) have appeared. Furthermore, it is at this stage of development that the first recognisable tablets of nacre can be detected. Colourmetrically, the uniform maroon background is now interrupted by oscillations of a pale cream colour, and is punctuated by a pattern of dots (that only occur on ridges) which are blue when overlying a maroon field and orange when overlying a cream field. This shell pattern may enhance the juvenile's ability to camouflage on the heterogeneous background of the CCA they inhabit at this stage of development.[5]

-

Live 1–2-month old juveniles

-

A 5 mm-long (3⁄16 in) juvenile shell of Haliotis asinina showing the tremata and ridges.

-

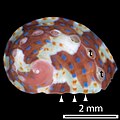

Juvenile shells of approximately 1–10 mm (1⁄32–13⁄32 in) in length have blue and orange dots, as shown here.

This pattern is gradually lost with growth, as the shell becomes thicker and more elongate. At 10 to 15 mm (13⁄32 to 19⁄32 in), this ornate colouration pattern begins to fade, with maroon and cream fields apparently blending to give a brown background. Blue and orange dots however persist on the ridges.[5]

With further growth, the ridge-valley structure fades to give rise to a smooth adult shell, with irregular brown-green triangles on a light brown background. These large scale morphological changes are accompanied by mineralogical and crystallographic changes. Well defined tablets of nacre are present in shells larger than approximately 5 mm (3⁄16 in) which are absent or poorly resolved in shells 1 mm (39 mils) or less. In larger shells, a ventral cap of CaCO

3 that underlies the tablets of aragonitic nacre continues to thicken.[5]

Overall, ontogenetic changes in Haliotis asinina shell pigmentation and structure match changes in the habitats occupied during development.[5]

-

Shells of animals a little larger than 10 mm (3⁄8 in) have dots but only on the shell ridges

-

Adult shell of Haliotis asinina. Note the similarity of the markings to the Sierpinski triangle.

The growth rate of Haliotis asinina is the fastest of all the abalones.[6] Individuals reach sexual maturity in one year.[6]

Anatomy

[edit] |

|

Human uses

[edit]The flesh of Haliotis asinina is edible, and it is usually collected for food and also for its shell in South East Asian countries.[4]

References

[edit]This article incorporates CC-BY-2.0 text (but not under GFDL) from reference.[5]

- ^ Peters, H. (2021). "Haliotis asinina". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T78749198A78772393. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T78749198A78772393.en.

- ^ Haliotis asinina Linnaeus, 1758. Retrieved through: World Register of Marine Species on 29 March 2010.

- ^ a b Haliotis asinina Donkey's ear abalone. Sealifebase.org accessed 10 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Poutiers, J. M. (1998). Gastropods in: FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes: The living marine resources of the Western Central Pacific Volume 1.[permanent dead link] Seaweeds, corals, bivalves and gastropods. Rome, FAO, 1998. page 385.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jackson D. J., Wörheide G. & Degnan B. M. (2007). "Dynamic expression of ancient and novel molluscan shell genes during ecological transitions". BMC Evolutionary Biology 7: 160. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-160.

- ^ a b Lucas T., Macbeth M., Degnan S. M., Knibb W. R. & Degnan B. M. (2006). "Heritability estimates for growth in the tropical abalone Haliotis asinina using microsatellites to assign parentage". Aquaculture 259(1–4): 146–152, abstract.

- ^ Jackson D. J., McDougall C., Green K., Simpson F., Wörheide G. & Degnan B. M. (2006). "A rapidly evolving secretome builds and patterns a sea shell". BMC Biology 4: 40. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-4-40.

- Linnaeus, C. 1758. Systemae naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differetiis, synonymis, locis.v. Holmiae : Laurentii Salvii 824 pp.

- Donovan, E. 1808. Conchology. In, The new Cyclopaedia or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences

- Springsteen, F.J. & Leobrera, F.M. 1986. Shells of the Philippines. Manila : Carfel Seashell Museum 377 pp., 100 pls.

- Wilson, B. 1993. Australian Marine Shells. Prosobranch Gastropods. Kallaroo, Western Australia : Odyssey Publishing Vol. 1 408 pp.

- Geiger, D.L. 2000 [1999]. Distribution and biogeography of the recent Haliotidae (Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda) world-wide. Bollettino Malacologico 35(5–12): 57-120

- Geiger, D.L. & Poppe, G.T. 2000. A Conchological Iconography. The family Haliotidae. Germany : ConchBooks 135 pp.

- Hylleberg, J & Kilburn, R.N. 2003. Marine Molluscs of Vietnam: Annotations, voucher material, and species in need of verification. Phuket Marine Biological Center Special Publication 28: 1–299

- Degnan, S.D., Imron, Geiger, D.L. & Degnan, B.M. 2006. Evolution in temperate and tropical seas: disparate patterns in southern hemisphere abalone (Mollusca: Vetigastropoda: Haliotidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 41: 249–256

- Streit, K., Geiger, D.L. & Lieb, B. 2006. Molecular phylogeny and the geographic origin of Haliotidae traced by haemocyanin sequences. Journal of Molluscan Studies 72: 111–116

External links

[edit]- Marie B., Marie A., Jackson D. J., Dubost L., Degnan B. M., Milet C. & Marin F. (2010). "Proteomic analysis of the organic matrix of the abalone Haliotis asinina calcified shell". Proteome Science [d] 8: 54. doi:10.1186/1477-5956-8-54.

- Photos of Haliotis asinina on Sealife Collection