Achrafieh

Achrafieh

الأشرفية | |

|---|---|

District | |

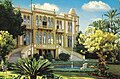

From left to right: Sursock Palace, Zahrat al-Ihsan Street, and a colourful street in Achrafieh | |

Location of Achrafieh within Beirut | |

| Coordinates: 33°53′15.21″N 35°31′14.72″E / 33.8875583°N 35.5207556°E | |

| Country | |

Achrafieh (Arabic: الأشرفية) is an upper-class area in eastern Beirut, Lebanon.[1] In strictly administrative terms, the name refers to a sector (secteur) centred on Sassine Square, the highest point in the city, as well as a broader quarter (quartier). In popular parlance, however, Achrafieh refers to the whole hill that rises above Gemmayze in the north and extends to Badaro in the south, and includes the Rmeil quarter.

Although there are traces of human activity dating back to the neolithic era, the modern suburb was heavily settled by Greek Orthodox merchant families from Beirut's old city in the mid-nineteenth century.[2] The area contains a high concentration of Beirut's Ottoman and French Mandate era architectural heritage. During the civil war, when Beirut was separated into eastern and western halves by the Green Line, Achrafieh changed from a mostly Christian residential area (compared to bustling, cosmopolitan Hamra, in Ras Beirut) to a commercial hub in its own right. In the early 2000s, the area became a focal point of the city's real estate boom.[3]

Overview

[edit]The etymology of Achrafieh most likely relates to the steep hill that defines the area, although this is contested.[4] The area centers on Beirut's highest point, the hill of Saint Dimitrios, and comprises neighbourhoods that slope towards the port in the north, and to what was once a vast pine forest, to the south. The name long predates the present administrative divisions of the Municipality of Beirut, and first appears to designate a suburb in Salih bin Yahya's History of Beirut, in the early 1400s.[5] The writer Elias Khoury recalls how the area was called the "little mountain" (al-jabal as-saghir) by locals, as if it were a small outpost of nearby Mount Lebanon on the coast.[6]

Administratively, Achrafieh today designates a quarter of the city, made up of 9 sectors (Achrafieh, Adlieh, Corniche el-Nahr, Furn el-Hayek, Ghabi, Hotel Dieu, Mar Mitr, Nasra, Sioufi). However, Saint Nicolas and Sursock Street, which are strictly within the quarter of Rmeil, have always been considered part of Achrafieh by local residents and real estate developers alike.[7] Similarly, certain southern parts of the administrative quarter, such as Adlieh, are generally not considered to be part of the area. Achrafieh is therefore defined somewhat nebulously and synonymously with East Beirut.

Achrafieh comprises residential areas characterized by narrow winding streets and cafes along with more commercial areas, with large apartment and office buildings and major arteries between central Beirut and the north-eastern suburbs. The following neighbourhoods are counted within Achrafieh:

- Accaoui, a hill leading from Gemmayze up to the Sursock neighbourhood

- Furn el-Hayek

- Karm el-Zeitoun, a densely populated settlement that was established by Armenian refugees in the 1920s, who were later joined by Syriac Christians. Syrian & Egyptian laborers (mainly males) as well as domestic migrant workers (mainly females) also reside in the area but live communally in shared apartments to minimize their living expenses[8]

- Mar Mitr, named after the Saint Demetrios Church, hosts one of the city's main Greek Orthodox cemeteries

- Mar Naqoula or Saint Nicolas, named after the parish church; includes Sursock Street with its old palatial villas, the St Nicolas Stairs (Escalier de l'Art) and many office buildings (Sofil Center, Ivory Building)

- Nasra, named after the Dames de Nazareth girls school

- Rue Monot

- Rue Huvelin

- Sassine Square, a busy road intersection atop the Saint Dimitrios hill, roughly coterminous with the Achrafieh sector, named after the Sassine family, the original landowners

- Sodeco Square

- Sioufi, a residential area on the southern slopes of the hill, built on land that was used for hunting in the mid twentieth century; named for the Sioufi family, which established a furniture factory here

- Tabaris Square and Abdel Wahab Street

History

[edit]There are traces of human activity on the slopes of Achrafieh in antiquity. The area included a necropolis, with archeological findings now in the National Museum of Beirut,[5] and a possible shrine around a water spring at what is today Saint Demetrios Church.[9]

Ottoman period

[edit]After several centuries of being a small, walled city, Beirut expanded rapidly in the mid-nineteenth century, as a result of increased trade and immigration, including refugees from inter-communal conflicts in Mount Lebanon and inland Syria.[10] As the old city became increasingly cramped and overpopulated, many Greek Orthodox trading families relocated from the port into semi-rural eastern areas, where they built spacious villas on the slopes of the hill, with large gardens and views commanding the port. These Orthodox families (including the Bustros, Gebeily, Trad, Tueni, and Sursock) made their money through the silk trade as well as money exchanging and tax collection, and were some of the largest property owners and tax payers in the city in the 1860s and 70s.[11] The Orthodox community's communal institutions followed them. The Greek Orthodox Archbishop's palace was also relocated from the Saint George Cathedral complex in downtown Beirut to the Sursock's neighbourhood overlooking the port. The Ecole des Trois Docteurs, founded in 1835 in the Orthodox Cathedral complex in central Beirut, moved eastward until it found its present location at the bottom of the Accaoui hill.[12]

The first palace was built by Nicolas Sursock, probably on what is now the St Nicolas Stairs, and hosted Russia's Grand Duke Nicholas when he visited Beirut in 1872.[13][14] Other villas included: Taswinat al-Tueni, a palace built by Georges Tueni in the early 1860s[15] and named for the fence that ringed the extensive grounds; the Fadlallah Bustros Palace, completed around 1863 and now housing the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Moussa Sursock's palace, completed around 1870; and Elias Sursock's palace, which hosted General Gouraud during the French Mandate and was demolished in the 1960s.[13] The last major villa was built for Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock in 1912, and upon his death, he left the palace to the Municipality of Beirut as a land grant or waqf, to become what is now the Sursock Museum.[16] These palatial villas remain emblematic of Achrafieh, with one such palace, built for Abdullah Bustros, being sold for $22 million in 2018.[17]

- Late Ottoman palatial residences in Achrafieh

-

Moussa Sursock's palace, completed around 1870

-

Alexandre Sursock's villa, now known as Villa Mokbel

-

Youssef Sursock's palace, now known as the Feghali House

-

Ibrahim Sursock's villa, completed around 1875

-

Nicolas Sursock's villa, completed in 1912

Besides the bourgeois families, many Christian refugees came to settle in the expanding suburbs, starting with the 1860 inter-communal conflict in Mount Lebanon, between Maronites and Druze, and in Damascus, between Orthodox Christians and Muslims.[18] Dimitri Youssef Debbas was one such refugee from the Damascus conflict, who settled in Achrafieh and wrote a memoir of the conflict. Historian Leila Fawaz describes how Dimitri Debbas was part of the first caravan fleeing Damascus, and placed into quarantine outside the city. The Bustros family persuaded the Mutessarif to allow the refugees into the town, and they were housed in the Ecole des Trois Docteurs, near the St George Cathedral. As the school became overcrowded, some were given shelter in Khalil Sursock's house, with families staying in the cellar, and men (including Dimitri Debbas) sleeping in the open.[19] Dimitri Debbas, who had been part of a successful business family in Damascus, rebuilt his wealth from Beirut and built a residence of his own in Achrafieh, on what is now known as Montee Debbas.[20]

Lebanese Civil War

[edit]

Given its large Christian population, Achrafieh was a focal point of conflict during the Lebanese Civil War. The area was the Beirut heartland of the Christian militias under the Lebanese Front. The Hundred Days' War in 1978 saw the Christian militias of the Lebanese Front fight the Syrian deterrent forces. In 1982, Lebanon's president-elect Bachir Gemayel was assassinated by a bomb explosion at the Kataeb office on Sassine Street. The documentary Beirut: The Last Home Movie (1987) by Jennifer Fox shows the day-to-day life of the Bustros family, inside the Tueni-Bustros palace during the early 1980s.[21] Mouna Bustros, who features in the film, was killed in 1989 when a rocket was fired from the nearby Rizk Tower at the palace. The Achrafieh experience of the war is also chronicled by Elias Khoury in his novel The Little Mountain (1989).[6]

Contemporary Achrafieh

[edit]In 2005, journalist Samir Kassir was assassinated by a bomb placed under his car at his residence in Achrafieh.[22]

In 2006, as part of the unrest surrounding the Danish cartoons of Muhammad, protestors torched the Danish embassy building in Tabaris and damaged the nearby Mar Maroun Church in Saifi.[23]

In October 2012, Wissam al-Hassan, head of the Intelligence Branch of Lebanon's Internal Security Force, was killed along with 8 others by a bomb on Sassine Street.[24]

Urbanism

[edit]

Achrafieh contains some of Beirut's largest remaining clusters of historic buildings from the late Ottoman and French Mandate periods. However, much of this heritage was destroyed during the Civil War (1975–1990), with many structures undergoing reconstruction in the following decades. The area also saw several construction booms (including during the Civil War, in the mid-1990s, and the 2000s), during which much of the built heritage including gardens was replaced with tower blocks to maximize land value.[3] Heritage buildings have been torn down for inheritance reasons, as a way of evicting tenants on so-called "old rents", or because of lack of maintenance.[3]

The area now contains the tallest towers in Beirut, including Sama Beirut near Sodeco, and SkyGate near Sassine Square. The area around Sursock Street has been rebranded by developers as a "golden triangle" (triangle d'or), as it has a balance between permissible population density and development rights (e.g., height of buildings). In 2003 ABC Achrafieh department store and shopping mall was built on what was Salam football field.

The built environment was badly affected by the explosion at Beirut's port in 2020, particularly in the northern parts of Achrafieh. An emergency law was promulgated in the immediate aftermath to stop the sale of land and evictions from houses around the port for the following two years.[25] Several civil society organizations, most notably the Beirut Heritage Initiative, have been working to restore groups of houses affected by the disaster.[26]

Very few of the remaining heritage buildings have any official protection, despite lobbying from civil society groups. A new bill was passed in 2017 by the Lebanese government to protect heritage sites around the city, marking a historical turning point for activists who have pressed for legislative action since the end of the war, but has not been ratified.[27]

Timeline

[edit]

- 1st century AD - Roman necropolis established on hill of St Dimitrios[28]

- 1839 - Reform under Egyptian administration allows expansion of city beyond walls[2]

- 1842 - Beirut takes over from Acre as seat of vilayet[2]

- 1860 - Inter-communal conflict in Mount Lebanon and Damascus leads to influx of Christian refugees, many of whom settle in Achrafieh[18]

- 1862 - Greek Orthodox Archbishop's residence moved from central Beirut to Achrafieh's Sursock Street[18]

- 1870 - Moussa Sursock's palace completed

- 1885 - Zahrat al-Ihsan school constructed

- 1909 - Grand Lycee Francophone established by Mission Laique Francaise, near what is now Sodeco

- 1910 - Ilyas Sioufi establishes the Sioufi Furniture Factory along with Sioufi Gardens

- 1912 - Nicolas Sursock's villa constructed[16]

- 1920 - Karm el-Zeitoun established as settlement for Armenian refugees[8]

- 1927 - Church of the Annunciation, demolished during the construction of Place de l'Etoile, rebuilt in Achrafieh

- 1931 - Danger Plan aims to make Beirut into a garden city, never put into effect

- 1952 - Nicolas Sursock dies and leaves his villa to the city as a waqf, stipulating that it will become a public museum[16]

- 1969 - Sassine Square construction works are completed

- 1978 - Hundred Days' War centers on Achrafieh

- 1982 - Bachir Gemayel assassinated at Beit al-Kataeb on Sassine Street

- 2003 - ABC Achrafieh department store and shopping mall built on what was Salam football field

- 2020 - Beirut's port explosion devastates the city, especially northern areas of Achrafieh

Education

[edit]

Schools and universities:

- Universite Saint Joseph de Beyrouth

- Grand Lycée Franco-Libanais[29]

- Collège de la Sagesse

- Greater Beirut Evangelical School[30]

- American University of Science and Technology

- University of Balamand, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences

- Zahrat al-Ihsan

- École des Trois Docteurs

- SSCC Sioufi

Places of worship

[edit]Catholic churches:

- St Youhanna Maronite Church, on Adib Ishak Street

Greek Orthodox churches:

- Notre Dame de l'Annonciation, historic church on Lebanon Street

- Saydet el Doukhoul Church

- St Dimitrios Church, hosting the Greek Orthodox cemetery for eastern Beirut

- St George Church, attached to the St George Hospital

- St Nicolas Church, an important parish church that was rebuilt in Byzantine style in the mid-twentieth century

Mosques:

- Beydoun Mosque

Syriac Orthodox churches:

- St Ephraim Church

Notable people

[edit]- Michel Sassine, Prominent Lebanese politician, MP for the district of Beirut for 24 years (1968-1992)

- Bachir Gemayel, born in the Achrafieh, he founded the Lebanese Forces. On 23 August 1982, he was elected President of Lebanon.

- Gebran Tueini, former editor and publisher of the daily paper An-Nahar

- Joe Kodeih, writer, actor and director

- Samir Assaf, CEO of HSBC Global Banking & Markets

- Nicolas Amiouni, rally driver

- Nancy Ajram, singer

See also

[edit]- Badaro

- Beirut Central District

- Grand Lycée Franco-Libanais

- Hekmeh BC

- Collège de la Sagesse

- Racing Beirut

- Hekmeh FC

Further reading

[edit]- Eddé, Carla. 2009. Beyrouth, naissance d’une capitale: 1918-1924. Paris: Actes Sud.

- Davie, May. 1993. La millat grecque-orthodoxe de Beyrouth, 1800-1940: Structuration interne et rapport a la cite. Doctoral thesis, Universite de Paris IV – Sorbonne.

- Davie, May. 1996. Beyrouth et ses faubourgs (1840-1940) : Une intégration inachevée. Beirut: Les Cahiers du Cermoc.

- Fawaz, Leila Tarazi. 1983. Merchants and migrants in nineteenth-century Beirut. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hanssen, Jens. 2005. Fin de siècle Beirut: The making of an Ottoman provincial capital. Oxford Historical Monographs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kamel, Leila Salameh. 1998. Un quartier de Beyrouth, Saint-Nicolas : structures familiales et structures foncières. Beirut: Dar el-Machreq.

- Kassir, Samir. 2010. Beirut. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Khoury, Elias. 1989. Little mountain. New York: Picador.

- Traboulsi, Fawwaz. 2007. A History of Modern Lebanon. London: Pluto Press.

- Trombetta, Lorenzo. 2009. “The private archive of the Sursuqs, a Beirut family of Christian notables: An early investigation.” Rivista degli Studi Orientali 82(1).

- Verdeil, Éric. 2012. Beyrouth et ses urbanistes : Une ville en plans (1946-1975). Beyrouth: Presses de l’Ifpo. [http://books.openedition.org/ifpo/2101].

References

[edit]- ^ Arsan, Andrew (2018). Lebanon: A Country in Fragments. Oxford University Press. p. 71. ISBN 9781787381087.

the core, Upper and middle class neighbourhoods in Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhael in Achrafieh.

- ^ a b c Davie, May (1996). Beyrouth et ses faubourgs: Une intégration inachevée (in French). Presses de l’Ifpo. ISBN 978-2-905465-09-2.

- ^ a b c Ashkar, Hisham (2018-05-04). "The role of laws and regulations in shaping gentrification". City. 22 (3): 341–357. doi:10.1080/13604813.2018.1484641. ISSN 1360-4813. S2CID 149478478.

- ^ "Live Achrafieh: history of street names and districts". Archived from the original on 2021-04-14. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

- ^ a b Kamel, Leila Salameh (1998). Un quartier de Beyrouth, Saint-Nicolas: structures familiales et structures foncières (in French). Beyrouth, Liban: Dar el-Machreq. p. 29. ISBN 978-2-7214-5010-4. OCLC 43920413.

- ^ a b Khoury, Elias (2007-11-27). Little Mountain. Picador. ISBN 978-1-4299-1694-3.

- ^ Maura Azar (2021). "Achrafieh: A Charming Community". Hayek Group. p. 19.

- ^ a b "Generative Art Conference, Milan". www.generativeart.com. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ Davie, May (2007-12-30). "Saint-Dimitri, un cimetière orthodoxe de Beyrouth". Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'Ouest. Anjou. Maine. Poitou-Charente. Touraine (in French) (114–4): 29–42. doi:10.4000/abpo.457. ISSN 0399-0826.

- ^ Traboulsi, Fawwaz (2012-07-17). A History of Modern Lebanon. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-3275-8.

- ^ Fatté Davie, May (1993-01-01). La millat grecque-orthodoxe de Beyrouth, 1800-1940 : structuration interne et rapport à la cité (These de doctorat thesis). Paris 4.

- ^ "Les 175 ans de l'École des Trois Docteurs". L'Orient-Le Jour. 2010-05-04. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ a b Ingea, Tania Rayes (2018). Portraits et palais : récit de famille autour de Victor et Hélène Sursock. Éditeur non identifié. ISBN 978-9953-0-4602-0. OCLC 1136120572.

- ^ Marozzi, Justin (2019-08-29). Islamic Empires: Fifteen Cities that Define a Civilization. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-241-19905-3.

- ^ Nalbandian, Salpy. "LibGuides: Beirut's Heritage Buildings: Achrafieh". aub.edu.lb.libguides.com. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ a b c "History". sursock.museum. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ "Le palais Abdallah Bustros à Achrafié vendu à 22 millions de dollars - M.R." Commerce du Levant (in French). 2018-01-24. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ a b c "Classé bâtiment historique, l'ancien archevêché grec-orthodoxe de Beyrouth a été ravagé par l'explosion du 4 août". L'Orient-Le Jour. 2020-10-12. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ Fawwāz, Layla Tarazī (1983). Merchants and migrants in nineteenth-century Beirut. Harvard University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-674-56925-3. OCLC 906424764.

- ^ Kassir, Samir (2012). Histoire de Beyrouth. Perrin. p. 138. ISBN 978-2-262-03924-0. OCLC 805034223.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ "Journalist Samir Kassir assassinated in Beirut blast". www.dailystar.com.lb. Archived from the original on 2021-07-31. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ Zoepf, Katherine; Fattah, Hassan M. (2006-02-05). "Protesters in Beirut Set Danish Consulate on Fire". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ "Attentat place Sassine : Wissam el-Hassan tué, des ténors de l'opposition accusent Damas". L'Orient-Le Jour. 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ Chehayeb, Kareem. "'In limbo': Beirut blast victims still struggling to return home". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ "Beirut Hertitage Initiative". daleel-madani.org. 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ Saade, Tamara (2017-10-31). "A Success For Beirut's Heritage, But Not Yet A Victory". Beirut Today. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ National Museum of Beirut exhibit

- ^ Home page. Grand Lycée Franco-Libanais. Retrieved on December 13, 2016. "Rue Beni Assaf B.P. 165-636 Achrafieh 1100 2060 - Beyrouth"

- ^ Home page

External links

[edit]- SOUWAR.com

- Ikamalebanon.com

- Lebanonatlas.com

- Article on the history of Ashrafieh and how it evolved through time - Interview with Former Ashrafieh MP Michel Sassine (December 2011): https://www.scribd.com/doc/77669439/Interview-on-the-History-of-Achrafieh-with-HE-Michel-Sassine-Dec-2011