Dreamcatcher

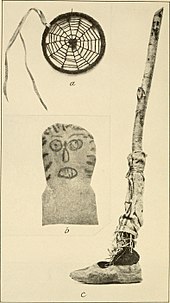

In some Native American and First Nations cultures, a dreamcatcher (Ojibwe: asabikeshiinh, the inanimate form of the word for 'spider')[1] is a handmade willow hoop, on which is woven a net or web. It may also be decorated with sacred items such as certain feathers or beads. Traditionally, dreamcatchers are hung over a cradle or bed as protection.[2] It originates in Anishinaabe culture as "the spider web charm" – asubakacin 'net-like' (White Earth Nation); bwaajige ngwaagan 'dream snare' (Curve Lake First Nation)[3] – a hoop with woven string or sinew meant to replicate a spider's web, used as a protective charm for infants.[2]

Dream catchers were adopted in the Pan-Indian Movement of the 1960s and 1970s and gained popularity as widely marketed "Native crafts items" in the 1980s.[4]

Ojibwe origin

[edit]

Ethnographer Frances Densmore in 1929 recorded an Ojibwe legend according to which the "spiderwebs" protective charms originate with Spider Woman, known as Asibikaashi; who takes care of the children and the people on the land. As the Ojibwe Nation spread to the corners of North America it became difficult for Asibikaashi to reach all the children.[2] So the mothers and grandmothers weave webs for the children, using willow hoops and sinew, or cordage made from plants. The purpose of these charms is apotropaic and not explicitly connected with dreams:

Even infants were provided with protective charms. Examples of these are the "spiderwebs" hung on the hoop of a cradle board. In old times this netting was made of nettle fiber. Two spider webs were usually hung on the hoop, and it was said that they "caught any harm that might be in the air as a spider's web catches and holds whatever comes in contact with it."[2]

Basil Johnston, an elder from Neyaashiinigmiing, in his Ojibway Heritage (1976) gives the story of Spider (Ojibwe: asabikeshiinh, "little net maker") as a trickster figure catching Snake in his web.[5][clarification needed]

Modern uses

[edit]

While dreamcatchers continue to be used in a traditional manner in their communities and cultures of origin, derivative forms of dreamcatchers were adopted into the Pan-Indian movement of the 1960s and 1970s as a symbol of unity among the various Native American cultures, or as a general symbol of identification with Native American or First Nations cultures.[4]

The name "dream catcher" was published in mainstream, non-Native media in the 1970s[6] and became widely known as a Native crafts item by the 1980s.[7] By the early 1990s, it was "one of the most popular and marketable" ones.[8]

In the course of becoming popular outside the Ojibwe Nation, and then outside the pan-Indian communities, various types of "dreamcatchers", many of which bear little resemblance to traditional styles, and that incorporate materials that would not be traditionally used, are now made, exhibited, and sold by New Age groups and individuals. Many Native Americans have come to see these imitation dreamcatchers as over-commercialized, offensively misappropriated and misused by non-Natives.[4]

A mounted and framed dreamcatcher is being used as a shared symbol of hope and healing by the Little Thunderbirds Drum and Dance Troupe from the Red Lake Indian Reservation in Minnesota. In recognition of the shared trauma and loss experienced, both at their school during the Red Lake shootings, and by other students who have survived similar school shootings, they have traveled to other schools to meet with students, share songs and stories, and gift them with the dreamcatcher. The dreamcatcher has been passed from Red Lake to students in several other towns where school shootings have occurred.[9][10][11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Free English-Ojibwe dictionary and translator - FREELANG". www.freelang.net.

- ^ a b c d Densmore, Frances (1929, 1979) Chippewa Customs. Minn. Hist. Soc. Press; pg. 113.

- ^ Jim Great Elk Waters, View from the Medicine Lodge (2002), p. 111.

- ^ a b c "During the pan-Indian movement in the 60's and 70's, Ojibway dreamcatchers started to get popular in other Native American tribes, even those in disparate places like the Cherokee, Lakota, and Navajo. ... Most of what you see when you search for 'Native American dreamcatchers' are cheap objects mass-produced in an Asian sweatshop somewhere or glued together by non-native teenagers with eBay accounts, and these 'dreamcatchers' often bear only vague resemblance to the actual American Indian craft it is supposed to represent." "Native American Dream catchers", Native-Languages

- ^ John Borrows, "Foreword" to Françoise Dussart, Sylvie Poirier, Entangled Territorialities: Negotiating Indigenous Lands in australia and Canada, University of Toronto Press, 2017.

- ^ "a hoop laced to resemble a cobweb is one of Andrea Petersen's prize possessions. It is a 'dream catcher'—hung over a Chippewa Indian infant's cradle to keep bad dreams from passing through. 'I hope I can help my students become dream catchers,' she says of the 16 children in her class. In a two-room log cabin elementary school on a Chippewa reservation in Grand Portage" The Ladies' Home Journal 94 (1977), p. 14.

- ^ "Audrey Speich will be showing Indian Beading, Birch Bark Work, and Quill Work. She will also demonstrate the making of Dream Catchers and Medicine Bags." The Society Newsletter (1985), p. 31.

- ^ Terry Lusty (2001). "Where did the Ojibwe dream catcher come from? | Windspeaker - AMMSA". www.ammsa.com. Sweetgrass; volume 8, issue 4: The Aboriginal Multi-Media Society. p. 19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Marysville School District receives dreamcatcher given to Columbine survivors By Brandi N. Montreuil, Tulalip News. Posted on November 7, 2014

- ^ "Showing Newtown they're not alone - CNN Video" – via edition.cnn.com.

- ^ Dreamcatcher for school shooting survivors (paywall)