Artus Quellinus II

Artus Quellinus II | |

|---|---|

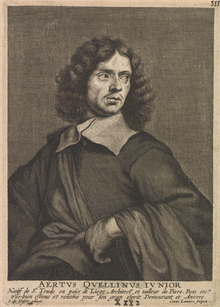

Artus Quellinus II, engraved by Conrad Lauwers after design by Jan de Duyts | |

| Born | 15 November 1625 |

| Died | 22 November 1700 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | Flemish |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Movement | Baroque |

Artus Quellinus II or Artus Quellinus the Younger (alternative first name: Arnold; variation on family name: Quellijn, Quellyn, Quellien, Quellin, Quellinius) (between 10 and 20 November 1625 – 22 November 1700) was a Flemish sculptor who played an important role in the evolution of Northern-European sculpture from High Baroque to Late Baroque.[1]

Life

[edit]

Artus Quellinus II was born at Sint-Truiden, into an artistic family. His uncle was the respected Antwerp sculptor Erasmus Quellinus I, whose son was Artus Quellinus I, the most successful Flemish Baroque sculptor of the mid 17th century. Artus II is likely to have received his training as a sculptor from his cousin Artus Quellinus I in Antwerp to where he must have moved from his native city of Sint-Truiden (then in the Prince-Bishopric of Liège, now in the Belgian province of Limburg). Artus Quellinus II became a master of the Guild of Saint Luke in Antwerp in 1650–51.[2]

Artus Quellinus II married Anna Maria Gabron, the sister of the painter Willem Gabron, in 1653. The couple had six children of whom three became artists: Artus Quellinus III and Thomas Quellinus were both successful sculptors whereas Cornelis Quellinus became a painter about whom little is known.[1]

The young Artus joined his cousin Artus Quellinus I in Amsterdam around 1653 where he became one of the members of the team of artists that worked under the direction of Artus I on the decoration of the newly built City Hall on the Dam Square.

The artist traveled to Italy and probably visited Turin, Florence and Rome between 1655 and 1657.[3] He was back in Antwerp in 1657 and became an Antwerp burgher on 11 May 1663. His wife died on 15 October 1668 and the next year Artus remarried to Cornelia Volders.[2] In the latter part of his life Quellinus received many commissions, primarily for church furnishings and tomb sculptures.[1]

His pupils include Alexander van Papenhoven, Thomas Quellinus, Jan van den Steen, (1633–1723), the Master of the St. Luke in Antwerp, Cornelis van Scheyck (1679–1680), Balten Rubbens (1685–1686), Adriaen Govaerts (1690–91) and Jacobus de Man (1694–95). As Artus Quellinus the Elder and the Younger resided at the same time in Antwerp for a long period it is not always clear from the records of the local Guild of Saint Luke (the so-called Liggeren) whether someone was a pupil of Artus the Younger or the Elder.[2] He died in Antwerp.

Work

[edit]Artus Quellinus II received many commissions from patrons in the Southern Netherlands as well as from other cultural centres of Europe, such as Copenhagen.[1]

Artus the Younger's style marked an evolution in Baroque sculpture in Flanders towards a more dramatic and expressive form. This distinguishes him from his cousin Artus I who had worked in Rome in the workshop of François Duquesnoy and upon his return in Flanders in the 1640s had helped introduce the Baroque style developed by François Duquesnoy, which was based on classical sculpture.[4] This style was less expressive than the Baroque style of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the main competitor of François Duquesnoy in Rome.

Artus the Younger's emphasis on emotion reveals a link with the work of Bernini and Lucas Faydherbe (1617–1697), the leading sculptor from Mechelen who had trained with Peter Paul Rubens. This is reflected in his preference for graceful bodies, flowing draperies, hair that is tussled by the wind and fine facial expressions with little sense of realism.[1][3]

The influence of Bernini became more pronounced after 1670 when Artus the Younger's work acquired a distinctively expressive and heroic character. This is apparent in the sculpture group of God the Father, in the St. Salvator's Cathedral in Bruges as well as in the Apotheosis of St. James in the St. James' Church in Antwerp. The twisted columns and the radial rays are borrowed directly from Bernini's Baldachin in the St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.[1] Here he created a new type of altar: freestanding, circular and open on all sides.[3]

Quellinus also made a number of more contemplative figures. The statue of St. Rosa of Lima in St. Paul's Church in Antwerp is an example of his more contemplative style and is regarded as one of the most beautiful sculptures from the Baroque in the Southern Netherlands.[3]

Selected works

[edit]- C. 1666–1670: St. Paul's Church, in Antwerp: the marble figure group of St. Rosa of Lima

- 1667: St. Walburga Church in Bruges: an oak pulpit remarkable for breaking with tradition: the barrel is not supported by heavy volutes but rests firmly on a single figure representing Faith (rather than the more usual multiple archangels and church fathers) and the stairs at the back. The barrel's form is traditional, except that the scallop shell of St. James has taken the place of the customary flat wooden surface of the sound board. The iconography was based on that of the Jesuit father Willem Hesius.

- 1668–1675: Herkenrode Abbey: The tomb of Abbess Anna-Catharina de Lamboy (now in the Virga Jesse Basilica in Hasselt).

- 1676: Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp: The tomb of Bishop Ambrosius Capello is the first work of Quellinus reflecting Bernini's ideas.

- 1682: St. Salvator's Cathedral in Bruges: the sculpture of God

- 1685: St. James' Church in Antwerp: high altar with The Apotheosis of St. James, which is one of his masterpieces.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Matthias Depoorter, Artus Quellinus II at: Baroque in the Southern Netherlands

- ^ a b c Artus Quellinus (II) at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (in Dutch)

- ^ a b c d Hans Vlieghe and Iris Kockelbergh. "Quellinus." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 25 March 2014

- ^ Helena Bussers, De baroksculptuur en het barok at Openbaar Kunstbezit Vlaanderen (in Dutch)

External links

[edit] Media related to Artus Quellinus II at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Artus Quellinus II at Wikimedia Commons