Arkalochori

Arkalochori

Αρκαλοχώρι | |

|---|---|

View from the south | |

| Coordinates: 35°08′39″N 25°15′38″E / 35.1441°N 25.2606°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Crete |

| Regional unit | Heraklion |

| Municipality | Minoa Pediada |

| Area | |

| • Municipal unit | 237.6 km2 (91.7 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[1] | |

| • Municipal unit | 8,547 |

| • Municipal unit density | 36/km2 (93/sq mi) |

| • Community | 3,927 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Website | http://www.arkalochori.gr |

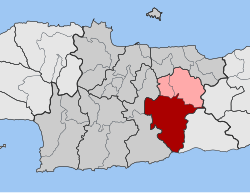

Arkalochori (Greek: Αρκαλοχώρι) is a town and a former municipality in the Heraklion regional unit, Crete, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Minoa Pediada, of which it is a municipal unit.[2] The municipal unit has an area of 237.589 km2 (91.734 sq mi).[3]

The town lies on the western edge of the Minoa Pediada plain, west of the Lasithi plateau, in central Crete. It contains the archaeological site of a Minoan sacred cave. The sacred cave was used from the third millennium to ca 1450 BCE, when the natural ceiling collapsed, fortuitously protecting some of the votive deposits there.

Town details

[edit]Located near Partira, the town is 32 km south of Heraklion. At the 2021 census the municipal unit had a population of 8,547 inhabitants.

Arkalochori is 3 km south from the recently discovered Minoan palace at the small village of Galatas. G. Rethemiotakis[4] has associated the votive objects of the Arkalochori cave with the Galatas palace.

The town hosts the Crete Half Marathon each October.

There is a statue of Napoleon Soukatzidis located in the town center. Sokatzidis was a Greek communist resistance fighter, whose family settled in Arkalochori after the 1923 population exchange.

The town was badly damaged in an earthquake measuring 5.8 on the Richter scale in September 2021.

Archaeology and the Arkalochori cave

[edit]The Arkalochori cave first came to scholarly attention in 1912, when peasants collected 20 kilos of Bronze Age weapons from the cave (known locally as "the treasure hole") and sold them for scrap metal in the port town of Candia (Iraklion). The ephor Iosif Hatzidakis, the first explorer of the central cave chamber of three, discovered masses of bronze votive weapons and a silver labrys (double axe).[5]

No gold was reported to the Ministry until 1934, when a child found a gold labrys that had been unearthed by a rabbit; the village turned out to rifle the site.[6] Prof. Spyridon Marinatos immediately took charge of the site[7] and discovered the side chambers, which had been blocked with debris from the collapse of the cave's natural roof. There were found, undisturbed, hundreds of bronze axes—twenty-five gold ones and seven silver ones—a hoard of bronze long swords, the longest (to 1.055 m) discovered in Europe,[8] and daggers and gold simulacra of weapons, cast "bun" ingots of copper alloy, a small altar, and pottery sherds that enabled the deposits to be given a date range of continuous occupation[9] from the late third millennium BCE to Late Minoan II (ca. 1500 to 1425 BCE).

The warlike implements, both actual weapons and their votive simulacra, are in strong contrast to the entirely peaceable finds at other Minoan cave sites.[10] The cave was not forgotten after the collapse, and votive offerings continued to be deposited at its mouth. The hill has remained sacred, though now associated with the prophet Elias.

At the Arkalochori cave, among the bronze and gold double axes, the second-millennium bronze Arkalochori Axe was excavated by Marinatos and Edith Eccles from 1934 to 1935. It has been suggested that markings on the axe might be Linear A, but Professor Glanville Price agrees with Louis Godart that "the characters on the axe are no more than a 'pseudo-inscription' engraved by an illiterate in uncomprehending imitation of authentic Linear A characters on other similar axes."[11]

The Psychro cave also contained labrys votive offerings.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Αποτελέσματα Απογραφής Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2021, Μόνιμος Πληθυσμός κατά οικισμό" [Results of the 2021 Population - Housing Census, Permanent population by settlement] (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority. 29 March 2024.

- ^ "ΦΕΚ B 1292/2010, Kallikratis reform municipalities" (in Greek). Government Gazette.

- ^ "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- ^ Rethemiotakis, "To neo minoiko Anaktoro ston Galata Pediados kai to 'Iero Spilaio' Arkalochoriou", in A. Karetsou, ed. Krites Thalassodromoi 1999:99-111

- ^ Hadjidakis, "A Minoan sacred cave at Arkalokhori in Crete", Annual of the British School at Athens 19 (1912-13:35-47).

- ^ Elizabeth Pierce Blegen, "News items from Athens", American Journal of Archaeology 39 (1935:134).

- ^ His suggestion that Arkalochori suited the birth cave of Zeus better than the Dictaean cave, which lies farther from Lyktos (modern Castelli Pediados), mentioned by Hesiod, was made from the start.

- ^ The "immensely long swords... with their sharply angular, finely grooved and elegant incised designs", which "have poor relations in the Cyclades", were categorized as a Cretan invention by N. K. Sandars, "The First Aegean Swords and Their Ancestry", American Journal of Archaeology 65.1 (January 1961), pp. 17-29.

- ^ Some scholars, such as Ellen Adams (Adams, "Power and Ritual in Neopalatial Crete: A Regional Comparison" World Archaeology 36.1, (March 2004:26-42, esp. p. 33f) see the gold axes as a hoard deposited at a single time; the lack of figurines at Arkalochori is noted.

- ^ Martin P. Nilsson's The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion (Lund, 1950:73ff) contains detailed descriptions of the site and findings.

- ^ Price, Glanville (2000). Encyclopedia of the languages of Europe. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-631-22039-8.

References

[edit]- Jones, Donald W. 1999 Peak Sanctuaries and Sacred Caves in Minoan Crete ISBN 91-7081-153-9

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Greek)

- Archaeological Atlas of the Aegean

- "Virtual Exhibition> Archaeological Museum of Heraklion". culture.gr. Directorate of the National Archive of Monuments. (in English) – includes the golden axe from Arkalochori