Archer Blood

Archer Kent Blood | |

|---|---|

| United States Consul General in Dacca | |

| In office March 1970 – June 1971 | |

| President | Richard Nixon |

| Succeeded by | position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 20, 1923 Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Died | September 3, 2004 (aged 81) Fort Collins, Colorado, United States |

| Spouse | Margaret Millward Blood |

| Children | 4[1] |

| Education | University of Virginia George Washington University |

Archer Kent Blood (March 20, 1923 – September 3, 2004) was an American career diplomat and academic. He served as the last American Consul General to Dhaka, Bangladesh (East Pakistan at the time). He is famous for sending the strongly worded "Blood Telegram" protesting against the atrocities committed in the Bangladesh Liberation War. He also served in Greece, Algeria, Germany, Afghanistan and ended his career as chargé d'affaires of the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, India, retiring in 1982.

Early life and education

[edit]Born in Chicago, Archer Blood graduated from high school in Lynchburg, Virginia. He received a bachelor's degree from the University of Virginia in 1943, then served in the U.S. Navy in the North Pacific in World War II. In 1947, he joined the Foreign Service, and received a master's degree in international relations from George Washington University in 1963.

Career

[edit]In 1970, Blood arrived in Dhaka, East Pakistan, as U.S. consul general.[2] When the Bangladesh genocide began, his consulate regularly reported events as they occurred to the White House, but received no response due to America's alliance with West Pakistan, fuelled in part by President Nixon's personal friendship with the then-President of Pakistan, Yahya Khan, as well as by National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger's desire to use Pakistan's cordial relationship with China as a pathway to resuming American relations with China.[3] Although Blood's initial cables failed to elicit a response from his government, they caused a stir with the American public when they were leaked, prompting Pakistan's foreign ministry to complain to the American government.[4]

With tensions in East Pakistan rising, Blood saw the independence of Bangladesh as an inevitability, remarking that "the ominous prospect of a military crackdown is much more than a possibility, but it would only delay, and ensure, the independence of [sic.] Bangla Desh."[5] After foreign journalists were rounded up and expelled from East Pakistan, Blood even sheltered a reporter who had sneaked away so that events could continue to be reported, in addition to sheltering Hindu Bengalis being targeted by the West Pakistani forces, despite being warned by the American government to refrain from doing so.[6]

Blood also played a role in the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, though this may not have been known in the United States at the time. A report suggests that one of the two triggers for the invasion was "Amin’s reception of acting American Chargé d’Affaires Archer Blood on October 27" in 1979.[7]

Throughout his career, Blood shared several oral histories with the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training.[8]

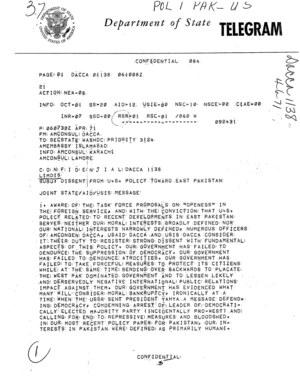

The Blood Telegram

[edit]

The Blood Telegram (April 6, 1971), sent via the State Department's Dissent Channel, was seen as the most strongly worded expression of dissent in the history of the U.S. Foreign Service.[9][10] It was signed by 20 members of the diplomatic staff.[11] The telegram stated:

Our government has failed to denounce the suppression of democracy. Our government has failed to denounce atrocities. Our government has failed to take forceful measures to protect its citizens while at the same time bending over backwards to placate the West Pak[istan] dominated government and to lessen any deservedly negative international public relations impact against them. Our government has evidenced what many will consider moral bankruptcy,... But we have chosen not to intervene, even morally, on the grounds that the Awami conflict, in which unfortunately the overworked term genocide is applicable, is purely an internal matter of a sovereign state. Private Americans have expressed disgust. We, as professional civil servants, express our dissent with current policy and fervently hope that our true and lasting interests here can be defined and our policies redirected in order to salvage our nation's position as a moral leader of the free world.

— U.S. Consulate (Dacca) Cable, Dissent from U.S. Policy Toward East Pakistan, April 6, 1971, Confidential, 5 pp. Includes Signatures from the Department of State. Source: RG 59, SN 70-73 Pol and Def. From: Pol Pak-U.S. To: Pol 17-1 Pak-U.S. Box 2535[12]

In an earlier telegram (March 27, 1971), Archer Blood wrote about American observations at Dhaka under the subject heading "Selective genocide":

1. Here in Dacca we are mute and horrified witnesses to a reign of terror by the Pak[istani] Military. Evidence continues to mount that the MLA authorities have list of AWAMI League supporters whom they are systematically eliminating by seeking them out in their homes and shooting them down

2. Among those marked for extinction in addition to the A.L. hierarchy are student leaders and university faculty. In this second category we have reports that Fazlur Rahman head of the philosophy department and a Hindu, M. Abedin, head of the department of history, have been killed. Razzak of the political science department is rumored dead. Also on the list are the bulk of MNA's elect and number of MPA's.

3. Moreover, with the support of the Pak[istani] Military. non-Bengali Muslims are systematically attacking poor people's quarters and murdering Bengalis and Hindus.

— U.S. Consulate (Dacca) Cable, Selective genocide, March 27, 1971[13]

Aftermath

[edit]Although Blood was scheduled for another 18-month tour in Dhaka, President Richard M. Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger recalled him from that position since his opposition went against their hopes of using the support of West Pakistan for diplomatic openings to China and to counter the power of the Soviet Union.[14][15][16] He was assigned to State Department's personnel office.[14] Government officials in 1972 admitted that they didn't believe the magnitude of the killings, labeling the telegram alarmist. His career was greatly marred by the telegram.[14] He wrote the book The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh – Memoirs of an American Diplomat, about his experience during the Bangladesh Liberation War.[17]

Archer Blood received the Christian A. Herter Award in 1971 for "extraordinary accomplishment involving initiative, integrity, intellectual courage and creative dissent".[14] The Blood Telegram was also a precursor to the formation of the State Department 'Dissent Channel' that formed in the following years, a mechanism through which agency officials could express formal critiques of United States foreign policy.[18]

Death and legacy

[edit]Blood died of arterial sclerosis on September 3, 2004, in Fort Collins, Colorado, where he had been living since 1993. His death made headlines in Bangladesh. Bangladesh sent a delegation to the funeral in Fort Collins and Mrs. Blood received numerous communiques from Bangladeshis. His contribution in shaping the moral contours of American diplomacy in 1971 was acknowledged by The Washington Post in its obituary.[14]

In May 2005, Blood was posthumously awarded the Outstanding Services Award by the Bangladeshi-American Foundation, Inc. (BAFI) at the First Bangladeshi-American Convention.[19] Blood received this Award for his role in 1970 and 1971 for the cause of humanity and his brave stance against the US official policy while the Pakistan army was engaged in a genocidal mission in what is now Bangladesh. His son, Peter Blood, accepted the award on behalf of the family. This was followed on December 13, 2005, by the dedication of the American Center Library, U.S. Embassy Dhaka, in the name of Archer K. Blood. Present at the ribbon-cutting ceremony were Chargé d'Affaires Judith Chammas, Mrs. Margaret Blood and her children, Shireen Updegraff and Peter Blood.

In 2022, the State Department named a conference room at its Foggy Bottom headquarters in Blood's honor.[20]

Publications

[edit]- The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh: Memoirs of an American Diplomat. Bangladesh: University Press Limited, 2002.

References

[edit]- ^ Hopey, Don (13 September 2004). "Obituary: Archer K. Blood / Longtime diplomat who taught at Allegheny College". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Gary J. Bass (2013). The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-307-70020-9.

- ^ Gary J. Bass (2013). The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. xi–xii. ISBN 978-0-307-70020-9.

- ^ Gary J. Bass (2013). The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 55, 57. ISBN 978-0-307-70020-9.

- ^ Gary J. Bass (2013). The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-307-70020-9.

- ^ Gary J. Bass (2013). The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 51, 59. ISBN 978-0-307-70020-9.

- ^ "The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan, 1979: Not Trump's Terrorists, Nor Zbig's Warm Water Ports". The National Security Archive. January 28, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ Blood, Archer K. (June 27, 1989). "Foreign Affairs Oral History Project" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by Henry Precht. Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ Dissent Channel in Foreign Affairs Manual 2 FAM 070 (PDF)

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher. "The Trial of Henry Kissinger", 2002

- ^ Gary J. Bass (2013). The Blood Telegram: Nixon, Kissinger, and a Forgotten Genocide. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-307-70020-9.

- ^ "Disent from U.S. Policy Toward East Pakistan" (PDF). George Washington University. April 6, 1971. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ "Telegram 959 From the Consulate General in Dacca to the Department of State". March 27, 1971. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Holley, Joe (23 September 2004). "Archer K. Blood; Dissenting Diplomat". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Bass, Gary (29 September 2013). "Nixon and Kissinger's Forgotten Shame". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Dymond, Jonny (11 December 2011). "The Blood Telegram". BBC Radio. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ "The peculiar global invisibility of 1971". The Daily Star. 2016-12-24. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ^ Nate Jones; Tom Blanton; Emma Sarfity, eds. (March 15, 2018). "Department of State's Dissent Channel Revealed". National Security Archive. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- ^ Bangladeshi-American Foundation, Inc

- ^ Schaffer, Michael (24 June 2022). "Is the State Department Trolling Henry Kissinger?". POLITICO. Retrieved 2022-06-28.

Further reading

[edit]- Sajit Gandhi The Tilt: The U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971 National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 79 December 16, 2002 contains links to the "Blood telegram" and a number of other U.S. declassified papers of that time.

- US Department of State on Foreign Relations and South Asia crisis 1969-1976

- Joe Galloway: Rest in Peace Archer Blood, American Hero

- Obituary Washington Post

- Bass, Gary Jonathan, 2013. The Blood Telegram. A Borzoi book.

External links

[edit]- 1923 births

- 2004 deaths

- University of Virginia alumni

- Elliott School of International Affairs alumni

- American expatriates in Pakistan

- Diplomats from Chicago

- United States Foreign Service personnel

- United States Navy personnel of World War II

- American expatriates in Afghanistan

- 20th-century American diplomats

- Allegheny College faculty