History of Somaliland

| History of Somaliland |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Somaliland, a country in the eastern Horn of Africa bordered by the Gulf of Aden, and the East African land mass, begins with human habitation tens of thousands of years ago. It includes the civilizations of Punt, the Ottomans, and colonial influences from Europe and the Middle East.

Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of Mecca fleeing prosecution during the first Hejira with Masjid al-Qiblatayn in Zeila being built before the Qiblah towards Mecca. It is one of the oldest mosques in Africa.[1] In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi wrote that Muslims were living along the northern Somali seaboard.[2] Various Somali Muslim kingdoms were established in the area in the early Islamic period.[3] In the 14th to 15th centuries, the Zeila-based Adal Sultanate battled the Ethiopian Empire,[4] at one point bringing the three-quarters of Christian Abyssinia under the control of the Muslim empire under military leader Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi[5]

In the early modern period, successor states to the Adal Sultanate began to flourish in the region, including the Isaaq Sultanate led by the Guled dynasty.[6][7][8] The modern Guled Dynasty of the Isaaq Sultanate was established in the middle of the 18th century by Sultan Guled.[9] The Sultanate had a robust economy and trade was significant at the main port of Berbera but also eastwards along the coast, with the Isaaq controlling various trade routes into the port cities.[10][6][8]

In the late 19th century, the United Kingdom signed agreements with the Gadabuursi, Issa, Habr Awal, Garhajis, Habr Je'lo and Warsangeli clans establishing the Somaliland Protectorate,[11][12][13] which was formally granted independence by the United Kingdom as the State of Somaliland on 26 June 1960. Five days later, on 1 July 1960, the State of Somaliland voluntarily united with the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somalia) to form the Somali Republic.[14][11]

The union of the two states proved problematic early on,[15] and in response to the harsh policies enacted by Somalia's Barre regime against the main clan family in Somaliland, the Isaaq, shortly after the conclusion of the disastrous Ogaden War,[16] a group of Isaaq businesspeople, students, former civil servants and former politicians founded the Somali National Movement in London in 1981, leading to a 10 year war of independence that concluded in the declaration of Somaliland's independence in 1991.[17]

Prehistory

[edit]

Somaliland has been inhabited since at least the Paleolithic. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished.[18] The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to the 4th millennium BC.[19] The stone implements from the Jalelo site in the north were also characterized in 1909 as important artefacts demonstrating the archaeological universality during the Paleolithic between the East and the West.[20]

According to linguists, the first Afro-Asiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic period from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley,[21] or the Near East.[22] Other scholars propose that the Afro-Asiatic family developed in situ in the Horn, with its speakers subsequently dispersing from there.[23]

The Laas Geel complex on the outskirts of Hargeisa in northwestern Somaliland dates back around 5,000 years, and has rock art depicting both wild animals and decorated cows.[24] Other cave paintings are found in the northern Dhambalin region, which feature one of the earliest known depictions of a hunter on horseback. The rock art is in the distinctive Ethiopian-Arabian style, dated to 1000 to 3000 BCE.[25][26] Additionally, between the towns of Las Khorey and El Ayo in eastern Somaliland lies Karinhegane, the site of numerous cave paintings of real and mythical animals. Each painting has an inscription below it, which collectively have been estimated to be around 2,500 years old.[27][28]

Antiquity

[edit]Land of Punt

[edit]

Most scholars locate the ancient Land of Punt in the Horn of Africa between present-day Opone in Somaliland, Somalia, Djibouti, and Eritrea. This is based in part on the fact that the products of Punt, as depicted on the Queen Hatshepsut murals at Deir el-Bahri, were abundantly found in the region but were less common or sometimes absent in the Arabian Peninsula. These products included gold and aromatic resins such as myrrh, and ebony; the wild animals depicted in Punt include giraffes, baboons, hippopotami, and leopards. Says Richard Pankhurst : "[Punt] has been identified with territory on both the Arabian and the Horn of Africa coasts. Consideration of the articles which the Egyptians obtained from Punt, notably gold and ivory, suggests, however, that these were primarily of African origin. ... This leads us to suppose that the term Punt probably applied more to African than Arabian territory."[29][30][31][32] The inhabitants of Punt procured myrrh, spices, gold, ebony, short-horned cattle, ivory and frankincense which was coveted by the Ancient Egyptians. An Ancient Egyptian expedition sent to Punt by the 18th dynasty Queen Hatshepsut is recorded on the temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahari, during the reign of the Puntite King Parahu and Queen Ati.[33]

-

Sculptures have the cobra emblem (uraeus) that is wedged in the personages headdress Discover in Berbera, Somaliland

Periplus

[edit]In the Classical era, the city states of Malao (Berbera) and Mundus ([Xiis/Heis) [See original map] prospered, and were deeply involved in the spice trade, selling myrrh and frankincense to The Romans and Egyptians Somaliland and Puntland became known as hubs for spices mainly cinnamon and the cities grew wealthy from it the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea tells us that the northern Somaliland and Puntland regions of modern-day Somalia were independent and competed with Aksum for trade.[34]

Early Islamic states

[edit]

With the introduction of Islam in the 7th century in what are now the Afar-inhabited parts of Eritrea and Djibouti, the region began to assume a political character independent of Ethiopia. Three Islamic sultanates were founded in and around the area named Shewa (a Semitic-speaking sultanate in eastern Ethiopia, modern Shewa province and ruled by the Mahzumi dynasty, related to Muslim Amharas and Argobbas), Ifat (another Semitic-speaking[35] sultanate located in eastern Ethiopia in what is now eastern Shewa) and Adal and Mora (Gadabursi Clan, Somali, and Harari vassal sultanate of Ifat by 1288, centered on Dakkar and later Harar, with Zeila as its main port and second city, in eastern Ethiopia and in Somaliland's Awdal region; Mora was located in what is now the southern Afar Region of Ethiopia and was subservient to Adal).[citation needed]

At least by the reign of Emperor Amda Seyon I (r. 1314-1344) (and possibly as early as during the reign of Yekuno Amlak or Yagbe'u Seyon), these regions came under Ethiopian suzerainty. During the two centuries that it was under Ethiopian control, intermittent warfare broke out between Ifat (which the other sultanates were under, excepting Shewa, which had been incorporated into Ethiopia) and Ethiopia. In 1403 or 1415[36] (under Emperor Dawit I or Emperor Yeshaq I, respectively), a revolt of Ifat was put down during which the Walashma ruler, Sa'ad ad-Din II, was captured and executed in Zeila, which was sacked. After the war, the reigning king had his minstrels compose a song praising his victory, which contains the first written record of the word "Somali". Upon the return of Sa'ad ad-Din II's sons a few years later, the dynasty took the new title of "king of Adal," instead of the formerly dominant region, Ifat.[citation needed]

The area remained under Ethiopian control for another century or so. However, starting around 1527 under the charismatic leadership of Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi (Gurey in Somali, Gragn in Amharic, both meaning "left-handed"), Adal revolted and invaded medieval Ethiopia. Regrouped Muslim armies with Ottoman support and arms marched into Ethiopia employing scorched earth tactics and slaughtered any Ethiopian that refused to convert from Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity to Islam.[37] Moreover, hundreds of churches were destroyed during the invasion, and an estimated 80% of the manuscripts in the country were destroyed in the process. Adal's use of firearms, still only rarely used in Ethiopia, allowed the conquest of well over half of Ethiopia, reaching as far north as Tigray. The complete conquest of Ethiopia was averted by the timely arrival of a Portuguese expedition led by Cristovão da Gama, son of the famed navigator Vasco da Gama. The Portuguese had been in the area earlier in early 16th centuries (in search of the legendary priest-king Prester John), and although a diplomatic mission from Portugal, led by Rodrigo de Lima, had failed to improve relations between the countries, they responded to the Ethiopian pleas for help and sent a military expedition to their fellow Christians. a Portuguese fleet under the command of Estêvão da Gama was sent from India and arrived at Massawa in February 1541. Here he received an ambassador from the Emperor beseeching him to send help against the Muslims, and in July following a force of 400 musketeers, under the command of Christovão da Gama, younger brother of the admiral, marched into the interior, and being joined by Ethiopian troops they were at first successful against the Somalis but they were subsequently defeated at the Battle of Wofla (28 August 1542), and their commander captured and executed. On February 21, 1543, however, a joint Portuguese-Ethiopian force defeated the Somali-Ottoman army at the Battle of Wayna Daga, in which al-Ghazi was killed and the war won.[citation needed]

Ahmed al-Ghazi's widow married Nur ibn Mujahid in return for his promise to avenge Ahmed's death, who succeeded Imam Ahmad, and continued hostilities against his northern adversaries until he killed the Ethiopian Emperor in his second invasion of Ethiopia, Emir Nur died in 1567. The Portuguese, meanwhile, tried to conquer Mogadishu but according to Duarta Barbosa never succeeded in taking it.[38] The Sultanate of Adal disintegrated into small independent states, many of which were ruled by Somali chiefs.[citation needed]

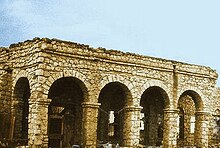

Early modern period

[edit]In the early modern period, successor states to the Adal Sultanate began to flourish in Somaliland, and by the 1600s the Somali lands split into numerous clan states, among them the Isaaq.[39] These successor states continued the tradition of castle-building and seaborne trade established by previous Somali empires.

These included the Isaaq Sultanate led by the Guled dynasty.[6][40] The Isaaq Sultanate was established in 1750 and was a Somali sultanate that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries.[6][40] It spanned the territories of the Isaaq clan, descendants of the Banu Hashim clan,[41] in modern-day Somaliland and Ethiopia. The sultanate was governed by the Rer Guled branch established by the first sultan, Sultan Guled Abdi, of the Eidagale clan.[42][43][44]

According to oral tradition, prior to the Guled dynasty the Isaaq clan-family were ruled by a dynasty of the Tolje'lo branch starting from, descendants of Ahmed nicknamed Tol Je'lo, the eldest son of Sheikh Ishaaq's Harari wife. There were eight Tolje'lo rulers in total who ruled for centuries starting from the 13th century.[45][46] The last Tolje'lo ruler Boqor Harun (Somali: Boqor Haaruun), nicknamed Dhuh Barar (Somali: Dhuux Baraar) was overthrown by a coalition of Isaaq clans. The once strong Tolje'lo clan were scattered and took refuge amongst the Habr Awal with whom they still mostly live.[47][48][49]

The modern Guled Dynasty of the Isaaq Sultanate was established in the middle of the 18th century by Sultan Guled of the Eidagale line of the Garhajis clan. His coronation took place after the victorious battle of Lafaruug in 1749 in which his father, a religious mullah Chief Abdi Chief Eisa successfully led the Isaaq in battle and defeated the Absame tribes who were allied to Garaad Dhuh Barar near Berbera where a century earlier the Isaaq clan expanded into.[9] After witnessing his leadership and courage, the Isaaq chiefs recognized his father Abdi who refused the position instead relegating the title to his underage son Guled while the father acted as the regent until the son came of age. Guled was crowned the as the first Sultan of the Isaaq clan in July 1750.[50] Sultan Guled thus ruled the Isaaq up until his death in 1808.[51]

After the death of Sultan Guled a dispute arose as to which of his 12 sons would succeed him. His eldest son Roble Guled, who was due to be crowned, was advised by his brother Du'ale to raid and capture livestock belonging to the Ogaden so as to serve the Isaaq sultans and dignitaries who would attend, as part of a plot to discredit the would-be sultan and usurp the throne. After the dignitaries were made aware of this fact by Du'ale they removed Roble from the line of succession and offered to crown Jama, his half brother, who promptly rejected the offer and suggested that Farah, Du'ale's full brother of Du'ale, son of Guled's fourth wife Ambaro Me'ad Gadidbe, be crowned.[51] The Isaaq subsequently crowned Farah,[52][51]

Early European Conflict

[edit]One of the most important settlements of the Sultanate was the city of Berbera which was one of the key ports of the Gulf of Aden. Caravans would pass through Hargeisa and the Sultan would collect tribute and taxes from traders before they would be allowed to continue onwards to the coast. Following a massive conflict between the Ayal Ahmed and Ayal Yunis branches of the Habr Awal over who would control Berbera in the mid-1840s, Sultan Farah brought both subclans before a holy relic from the tomb of Aw Barkhadle. An item that is said to have belonged to Bilal Ibn Rabah.

When any grave question arises affecting the interests of the Isaakh tribe in general. On a paper yet carefully preserved in the tomb, and bearing the sign-manual of Belat [Bilal], the slave of one [of] the early khaleefehs, fresh oaths of lasting friendship and lasting alliances are made...In the season of 1846 this relic was brought to Berbera in charge of the Haber Gerhajis, and on it the rival tribes of Aial Ahmed and Aial Yunus swore to bury all animosity and live as brethren.[53]

With the new European incursion into the Gulf of Aden and Horn of Africa contact between Somalis and Europeans on African soil would happen again for the first time since the Ethiopian–Adal war.[54] When a British vessel named the Mary Anne attempted to dock in Berbera's port in 1825 it was attacked and multiple members of the crew were massacred by the Habr Awal. In response the Royal Navy enforced a blockade and some accounts narrate a bombardment of the city.[55][6] In 1827 two years later the British arrived and extended an offer to relieve the blockade which had halted Berbera's lucrative trade in exchange for indemnity. Following this initial suggestion the Battle of Berbera 1827 would break out.[56][6] After the Isaaq defeat, 15,000 Spanish dollars was to be paid by the Isaaq Sultanate leaders for the destruction of the ship and loss of life.[55] In the 1820s Sultan Farah Sultan Guled of the Isaaq Sultanate penned a letter to Sultan bin Saqr Al Qasimi of Ras Al Khaimah requesting military assistance and joint religious war against the British.[57] This would not materialize as Sultan Saqr was incapacitated by prior Persian Gulf campaign of 1819 and was unable to send aid to Berbera. Alongside their stronghold in the Persian Gulf & Gulf of Oman the Qasimi were very active both militarily and economically in the Gulf of Aden and were given to plunder and attack ships as far west as the Mocha on the Red Sea.[58] They had numerous commercial ties with the Somalis, leading vessels from Ras Al Khaimah and the Persian Gulf to regularly attend trade fairs in the large ports of Berbera and Zeila and were very familiar with the Isaaq Sultanate respectively.[59][60]

British Somaliland

[edit]

The British Somaliland protectorate was initially ruled from British India (though later on by the Foreign Office and Colonial Office), and was to play the role of increasing the British Empire's control of the vital Bab-el-Mandeb strait which provided security to the Suez Canal and safety for the Empire's vital naval routes through the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

Resentment against the British authorities grew: Britain was seen as excessively profiting from the thriving coastal trading and farming occurring in the territory.[citation needed] Beginning in 1899, religious scholar Mohammed Abdullah Hassan began a campaign to wage a holy war.[61] Hassan raised an army united through the Islamic faith[62] and established the Dervish State, fighting Ethiopian, British, and Italian forces,[63] at first with conventional methods but switching to guerilla tactics after the first clash with the British.[61] The British launched four early expeditions against him, with the last one in 1904 ending in an indecisive British victory.[64] A peace agreement was reached in 1905, and lasted for three years.[61] British forces withdrew to the coast in 1909. In 1912 they raised a camel constabulary to defend the protectorate, but the Dervishes destroyed this in 1914.[64] In the First World War the new Ethiopian Emperor Iyasu V reversed the policy of his predecessor, Menelik II, and aided the Dervishes,[65] supplying them with weapons and financial aid. Germany sent Emil Kirsch, a mechanic, to assist the Dervish Forces as an armourer at Taleh[66] from 1916–1917,[64] and encouraged Ethiopia to aid the Dervishes while promising to recognise any territorial gains made by either of them.[67] The Ottoman Empire sent a letter to Hassan in 1917 assuring him of support and naming him "Emir of the Somali nation".[66] At the height of his power, Hassan led 6000 troops, and by November 1918 the British administration in Somaliland was spending its entire budget trying to stop Dervish activity. The Dervish state fell in February 1920 after a British campaign led by aerial bombing.[64]

Sporadic uprisings were to occur for decades afterwards, however on a much reduced scale with improved British infrastructural spending and a more benign, less paternalistic set of public policy.

During the East African Campaign of WWII, the protectorate was occupied by Italy in August 1940, but recaptured by the British in summer 1941. Some Italian guerrilla fighting (Amedeo Guillet) lasted until 1942.

The conquest of British Somaliland was Italy's only victory (without the cooperation of German troops) in WWII against the Allies.

-

Aerial bombardment of Dervish forts in Taleh.

-

Map of invasion route of the Italian conquest of British Somaliland in August 1940

-

Buralleh (Buralli) Robleh, Sub-Inspector of Police of Zeila, and General Gordon, Governor of British Somaliland, in Zeila (1921).

State of Somaliland

[edit]In 1947, the entire budget for the administration of the British Somaliland protectorate was only £213,139.[68]

In May 1960, the British Government stated that it would be prepared to grant independence to the then Somaliland protectorate. The Legislative Council of British Somaliland passed a resolution in April 1960 requesting independence. The legislative councils of the territory agreed to this proposal.[69]

In April 1960, leaders of the two territories met in Mogadishu and agreed to form a unitary state. An elected president was to be head of state. Full executive powers would be held by a prime minister answerable to an elected National Assembly of 123 members representing the two territories.

On 26 June 1960, the British Somaliland protectorate gained independence as the State of Somaliland before uniting five days later with the Trust Territory of Somalia to form the Somali Republic (Somalia) on 1 July 1960.[70][71]

The legislature appointed the speaker Hagi Bashir Ismail Yousuf as first President of the Somali National Assembly and, the same day, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar become President of the Somali Republic.

-

Agreements and Exchanges of Letters between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of Somaliland in connexion with the Attainment of Independence by Somaliland[72]

-

The Somaliland Protectorate Constitutional Conference, London, May 1960 in which it was decide that 26 June be the day of Independence, and so signed on 12 May 1960. Somaliland Delegation: Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal, Ahmed Haji Dualeh, Ali Garad Jama and Haji Ibrahim Nur. From the Colonial Office: Ian Macleod, D. B. Hall, H. C. F. Wilks (Secretary)

Separatism

[edit]

At the second national meeting of the Burao grand conference on May 18, the Somali National Movement Central Committee, with the support of a meeting of elders representing the major clans in the Northern Regions, declared the restoration of the Republic of Somaliland in the territory of the former British Somaliland protectorate and formed a government for the self-declared state.[74] This followed the collapse of the central government in Somalia in the Somali Civil War. However, the region's self-declared independence remains unrecognized by any country or international organization.[75][76]

-

Exhumed skeletal remains of victims of the Isaaq genocide found from a mass grave site located in Berbera, Somaliland.

-

The MiG monument in Hargeisa commemorating the Somaliland region's breakaway attempt from the rest of Somalia during the 1980s. It serves as a symbol of struggle for the province's residents.[77]

-

War-damaged houses in Hargeisa, a capital of Somaliland (1991).

-

A destroyed M47 Patton in Somaliland, left behind wrecked from the Somali Civil War.

-

Presidential decree ratifying the Somaliland constitution by Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal

-

Celebrating Somaliland'ś Independence Day, 18 May 2016

References

[edit]- ^ Briggs, Phillip (2012). Somaliland. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-84162-371-9.

- ^ Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 25. Americana Corporation. 1965. p. 255.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lewispohoawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-0-932415-19-6., page 45

- ^ Saheed A. Adejumobi, The History of Ethiopia, (Greenwood Press: 2006), p.178

- ^ a b c d e f Ylönen, Aleksi Ylönen (28 December 2023). The Horn Engaging the Gulf Economic Diplomacy and Statecraft in Regional Relations. Bloomsbury. p. 113. ISBN 9780755635191.

- ^ "Somali Traditional States". www.worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ a b J. A. Suárez (2023). Suárez, J. A. Geopolítica De Lo Desconocido. Una Visión Diferente De La Política Internacional [2023]. p. 227. ISBN 979-8393720292.

- ^ a b "Maxaad ka taqaana Saldanada Ugu Faca Weyn Beesha Isaaq". irmaannews.com. 13 February 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (3 February 2017). I.M Lewis: Peoples of the Horn of Africa. Routledge. ISBN 9781315308173.

- ^ a b Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 378–384.

- ^ Laitin, David D. (1977). Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-226-46791-7.

- ^ Issa-Salwe, Abdisalam M. (1996). The Collapse of the Somali State: The Impact of the Colonial Legacy. London: Haan Associates. pp. 34–35. ISBN 1-874209-91-X.

- ^ "Somalia". Archived from the original on 9 February 2006. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ Salih, Mohamed Abdel Rahim Mohamed; Wohlgemuth, Lennart (1 January 1994). Crisis Management and the Politics of Reconciliation in Somalia: Statements from the Uppsala Forum, 17–19 January 1994. Nordic Africa Institute. ISBN 9789171063564.

- ^ Kapteijns, Lidwien (18 December 2012). Clan Cleansing in Somalia: The Ruinous Legacy of 1991. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0758-3.

- ^ Richards, Rebecca (24 February 2016). Understanding Statebuilding: Traditional Governance and the Modern State in Somaliland. Routledge. ISBN 9781317004660.

- ^ Peter Robertshaw (1990). A History of African Archaeology. J. Currey. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-435-08041-9.

- ^ S. A. Brandt (1988). "Early Holocene Mortuary Practices and Hunter-Gatherer Adaptations in Southern Somalia". World Archaeology. 20 (1): 40–56. doi:10.1080/00438243.1988.9980055. JSTOR 124524. PMID 16470993.

- ^ H.W. Seton-Karr (1909). "Prehistoric Implements From Somaliland". 9 (106). Man: 182–183. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Zarins, Juris (1990), "Early Pastoral Nomadism and the Settlement of Lower Mesopotamia", (Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research)

- ^ Diamond J, Bellwood P (2003) Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions SCIENCE 300, doi:10.1126/science.1078208

- ^ Blench, R. (2006). Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. Rowman Altamira. pp. 143–144. ISBN 0-7591-0466-2. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Bakano, Otto (24 April 2011). "Grotto galleries show early Somali life". AFP. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Mire, Sada (2008). "The Discovery of Dhambalin Rock Art Site, Somaliland". African Archaeological Review. 25 (3–4): 153–168. doi:10.1007/s10437-008-9032-2. S2CID 162960112. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (17 September 2010). "UK archaeologist finds cave paintings at 100 new African sites". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Hodd, Michael (1994). East African Handbook. Trade & Travel Publications. p. 640. ISBN 0-8442-8983-3.

- ^ Ali, Ismail Mohamed (1970). Somalia Today: General Information. Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Somali Democratic Republic. p. 295.

- ^ Shaw & Nicholson, p.231.

- ^ Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.147

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (2001). The Ethiopians: A history. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-631-22493-8.

- ^ Hatshepsut's Temple at Deir El Bahari By Frederick Monderson

- ^ Breasted 1906–07, pp. 246–295, vol. 1.

- ^ "Ancient Harbours of Northern Somalia and Colonial Anti-African Historiography". Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Pankhurst, Richard. The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th century (Asmara, Eritrea: The Red Sea, Inc., 1997)

- ^ Al-Maqrizi gives the former date, while the Walashma chronicle gives the latter.

- ^ Somalia: From The Dawn of Civilization To The Modern Times: Chapter 8: Somali Hero - Ahmad Gurey (1506-43) Archived 2005-03-09 at the Wayback Machine CivicsWeb

- ^ J. Makong'o & K. Muchanga;Peak Revision K.C.S.E. History & Government, Page 50

- ^ Minahan, James B. (1 August 2016). Encyclopedia of Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups around the World. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 184–185. ISBN 979-8-216-14892-0.

- ^ a b Arafat, S. M. Yasir. Suicidal Behavior in Muslim Majority Countries: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Springer Nature. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-981-97-2519-9.

- ^ I. M. Lewis, A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, (LIT Verlag Münster: 1999), p. 157.

- ^ "Taariikhda Beerta Suldaan Cabdilaahi ee Hargeysa | Somalidiasporanews.com" (in Somali). Archived from the original on 19 February 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Genealogies of the Somal. Eyre and Spottiswoode (London). 1896.

- ^ "Taariikhda Saldanada Reer Guuleed Ee Somaliland.Abwaan:Ibraahim-rashiid Cismaan Guure (aboor). | Togdheer News Network". Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ "Degmada Cusub Ee Dacarta Oo Loogu Wanqalay Munaasibad Kulmisay Madaxda Iyo Haldoorka Somaliland". Hubaal Media. 7 October 2017. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Taariikhda Toljecle". www.tashiwanaag.com. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ "Taariikhda Boqortooyadii Axmed Sheikh Isaxaaq ee Toljecle 1787". YouTube.

- ^ Hunt, John Anthony (1951). A General Survey of the Somaliland Protectorate 1944-1950: Final Report on "An Economic Survey and Reconnaissance of the British Somaliland Protectorate 1944-1950," Colonial Development and Welfare Scheme D. 484. To be purchased from the Chief Secretary. p. 169.

- ^ NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Working Paper No. 65 Pastoral society and transnational refugees: population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia 1988 - 2000 Guido Ambroso, Table 1, pg.5

- ^ "Maxaad ka taqaana Saldanada Ugu Faca Weyn Beesha Isaaq oo Tirsata 300 sanno ku dhawaad?". 13 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Jama, Rashid (2012). Sheekadii Magan Suldaan Guuleed "Magan-Gaabo" (circa 1790-1840).

- ^ Genealogies of the Somal. Eyre and Spottiswoode (London). 1896.

- ^ a b "The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society Volume 19 p.61-62". 1849.

- ^ The Collapse of the Somali State: The Impact of the Colonial Legacy, pg 9

- ^ a b Laitin, David D. (1977). Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. 9780226467917. p. 70. ISBN 9780226467917.

- ^ J. A. Suárez (2023). Suárez, J. A. Geopolítica De Lo Desconocido. Una Visión Diferente De La Política Internacional [2023]. p. 227. ISBN 979-8393720292.

- ^ Al Qasimi, Sultan bin Muhammad (1996). رسالة زعماء الصومال إلى الشيخ سلطان بن صقر القاسمي (in Arabic). p. ١٧.

- ^ Davies, Charles E. (1997). The Blood-red Arab Flag: An Investigation Into Qasimi Piracy, 1797-1820. University of Exeter Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780859895095.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1965). "The Trade of the Gulf of Aden Ports of Africa in the Early Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 3 (1): 36–81. JSTOR 41965718.

- ^ Al Qasimi, Sultan bin Muhammad (1996). رسالة زعماء الصومال إلى الشيخ سلطان بن صقر القاسمي (in Arabic). p. ١٢.

- ^ a b c Abdi Ismail Samatar, The State and Rural Transformation in Northern Somalia, 1884-1986, page 38-39

- ^ Mohamoud, Abdullah A (2006). State collapse and post-conflict development in Africa: the case of Somalia (1960-2001) (illustrated ed.). Purdue University Press. p. 71. ISBN 1-55753-413-6. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ^ Pecastaing, Camille (2011). Jihad in the Arabian sea. Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-1376-2.

- ^ a b c d Omissi, David E (1990). Air Power and Colonial Control: The Royal Air Force, 1919–1939. Manchester University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0-7190-2960-0.

- ^ Foster, Mary LeCron; Rubinstein, Robert A (1986). Peace and war: cross-cultural perspectives. Transaction Publishers. p. 139. ISBN 0-88738-619-9.

- ^ a b Lewis, Ioan M. (2002). A modern history of the Somali: nation and state in the Horn of Africa (illustrated ed.). James Currey. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-8214-1495-8.

With the not-disinterested support of the Turkish and German Consuls in Ethiopia, the new Emperor conceived the aim of creating a vast Muslim Empire in NE Africa. To this end he entered into relations with Sayyid Muhammad, supplying him with financial aid and arms, and arranged for a German mechanic called Emil Kirsch to join the Dervishes and work for them as an armourer at their new headquarters at Taleh where a formidable ring of fortresses had been built by Yemeni masons. Before his pathetically unsuccessful bid for freedom from his exacting masters, Kirsch served the Dervishes well...In 1917, the Italian Administration of Somalia intercepted a document from the Turkish government which assured the Sayyid of support and named him Emir of the Somali nation.

- ^ Shinn, David Hamilton; Ofcansky, Thomas P; Prouty, Chris (2004). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia (illustrated ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 405. ISBN 0-8108-4910-0.

- ^ Ofcansky and LaVerle Berry, Thomas P. "Ethiopia in World War II". A Country Study: Ethiopia. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 29 October 2004. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Somali Independence Week Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Somalia". Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, The New Encyclopædia Britannica, (Encyclopædia Britannica: 2002), p.835

- ^ http://foto.archivalware.co.uk/data/Library2/pdf/1960-TS0044.pdf Archived 14 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Mohamud Omar Ali; Koss Mohammed; Michael Walls. "Peace in Somaliland: An Indigenous Approach to State-Building" (PDF). Academy for Peace and Development. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

On 18 May 1991 at this second national meeting, the SNM Central Committee, with the support of a meeting of elders representing the major clans in the Northern Regions, declared the restoration of the Republic of Somaliland, covering the same area as that of the former British Protectorate. The Burao conference also established a government for the Republic

- ^ Mohamud Omar Ali; Koss Mohammed; Michael Walls. "Peace in Somaliland: An Indigenous Approach to State-Building" (PDF). Academy for Peace and Development. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

On 18th May 1991 at this second national meeting, the SNM Central Committee, with the support of a meeting of elders representing the major clans in the Northern Regions, declared the restoration of the Republic of Somaliland, covering the same area as that of the former British Protectorate. The Burao conference also established a government for the Republic

- ^ Lacey, Marc (5 June 2006). "Hargeysa Journal; The Signs Say Somaliland, but the World Says Somalia". The New York Times. p. 4. Archived from the original on 27 June 2011.

- ^ "UN in Action: Reforming Somaliland's Judiciary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Close Residents of Somaliland sit under a war memorial of a MiG fighter jet in the centre of town in Hargeisa". Reuters. 19 May 2013. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

![Agreements and Exchanges of Letters between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of Somaliland in connexion with the Attainment of Independence by Somaliland[72]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7b/Independence_Day_State_of_Somaliland.png/79px-Independence_Day_State_of_Somaliland.png)

![The MiG monument in Hargeisa commemorating the Somaliland region's breakaway attempt from the rest of Somalia during the 1980s. It serves as a symbol of struggle for the province's residents.[77]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a0/Hargeysa_memorial.jpg/120px-Hargeysa_memorial.jpg)