Dragon King

| Dragon King | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

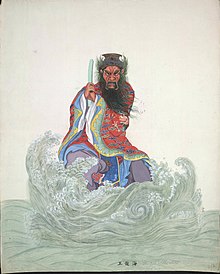

Dragon King of the Seas (海龍王), painted in the first half of the 19th century. | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 龍王 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 龙王 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Dragon King Dragon Prince | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 龍神 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 龙神 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Dragon God | ||||||

| |||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Long Vương | ||||||

| Chữ Hán | 龍王 | ||||||

The Dragon King, also known as the Dragon God, is a Chinese water and weather god. He is regarded as the dispenser of rain, commanding over all bodies of water. He is the collective personification of the ancient concept of the lóng in Chinese culture.

There are also the cosmological "Dragon Kings of the Four Seas" (四海龍王; Sihai Longwang).

Besides being a water deity, the Dragon God frequently also serves as a territorial tutelary deity, similarly to Tudigong "Lord of the Earth" and Houtu "Queen of the Earth".[1]

Singular Dragon King

[edit]The Dragon King has been regarded as holding dominion over all bodies of water,[a] and the dispenser of rain,[3] in rituals practiced into the modern era in China. One of his epithets is Dragon King of Wells and Springs.[4]

Rainmaking rituals

[edit]Dragon processions have been held on the fifth and sixth moon of the lunar calendar all over China, especially on the 13th day of the sixth moon, held to be the Dragon King's birthday, as ritualized supplication to the deity to make rain.[3] In Changli County, Hebei Province a procession of sorts carried an image of the Dragon King in a basket and made circuit around nearby villages, and the participants would put out in front of their house a piece of yellow paper calligraphed with the text: "The position [=tablet] of the Dragon King of the Four Seas 四海龍王之位, Five Lakes, Eight Rivers and Nine Streams", sprinkle it with water using willow withes, and burning incense next to it. This ritual was practiced in North of China into the 20th century.[2][5]

In the past, there used to be Dragon King miao shrines all over China, for the folk to engage in the worship of dragon kings, villages in farm countries would conduct rites dedicated to the Dragon Kings seeking rain.[6]

Daoist pantheon

[edit]Within the Daoist pantheon, the Dragon King is regarded the zoomorphic representation of the yang masculine power of generation. The dragon king is the king of the dragons and he also controls all of the creatures in the sea. The dragon king gets his orders from the Jade Emperor.[citation needed]

Dragon Kings of the Five Regions

[edit]| Dragons of the Five Regions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Historically there arose a cult of the Five Dragon Kings. The name Wufang longwang (五方龍王, "Dragon Kings of the Five Regions/Directions") is registered in Daoist scripture from the Tang dynasty, found in the Dunhuang caves.[7] Veneration of chthonic dragon god(s) of the five directions still persists today in southern areas, such as Canton and Fujian.[8] It has also been conflated with the cult of Lord Earth, Tugong (Tudigong), and inscriptions on tablets invoke the Wufang wutu longshen (五方五土龍神, "Dragon Spirits of the Five Directions and Five Soils") in rituals current in Southeast Asia (Vietnam).[9]

Description

[edit]The Azure Dragon or Blue-Green Dragon (靑龍 Qīnglóng), or Green Dragon (蒼龍 Cānglóng), is the Dragon God of the east, and of the essence of spring.[3] The Red Dragon (赤龍 Chìlóng or 朱龍 Zhūlóng, literally "Cinnabar Dragon", "Vermilion Dragon") is the Dragon God of the south and of the essence of summer.[3] The White Dragon (白龍 Báilóng) is the Dragon God of the west and the essence of autumn. The Yellow Dragon (黃龍 Huánglóng) is the Dragon God of the center, associated with (late) summer.[3][b] The Black Dragon (黑龍 Hēilóng), also called "Dark Dragon" or "Mysterious Dragon" (玄龍 Xuánlóng), is the Dragon God of the north and the essence of winter.[3]

Broad history

[edit]

Dragons of the Five Regions/Directions existed in Chinese custom,[12] established by the Former Han period (Cf. §Origins below)[12] The same concept couched in "dragon king" (longwang) terminology was centuries later,[13] the term "dragon king" being imported from India (Sanskrit naga-raja),[14] vis Buddhism,[8] introduced in the 1st century AD during the Later Han.[15]

The five "Dragon Kings" which were correlated with the Five Colors and Five Directions are attested uniquely in one work among Buddhist scriptures (sūtra), called the Foshuo guanding jing (佛說灌頂經; "Consecration Sūtra Expounded by the Buddha" early 4th century).[d][18] Attributed to Po-Srimitra, it is a pretended translation, or "apocryphal sutra" (post-canonical text),[16][19] but its influence on later rituals (relating to entombment) is not dismissable.[19]

The dragon king cult was most active around the Sui-Tang dynasty, according to one scholar,[20] but another observes that the cult spread farther afield with the backing of Song dynasty monarchs who built Dragon King Temples (or rather Taoist shrines),[7] and Emperor Huizong of Song (12th century) conferred investiture upon them as local kings.[21] But the dragon king and other spell incantations came to be discouraged in Buddhism within China, because they were based on eclectic (apocryphal) sutras and the emphasis grew for the orthodox sutras,[22] or put another way, the quinary system (based on number 5) was being superseded by the number 8 or number 12 being held more sacred.[23]

During the Tang period, the dragon kings were also regarded as guardians that safeguard homes and pacify tombs, in conjunction with the worship of Lord Earth.[24] Buddhist rainmaking ritual learned Tang dynasty China by

The concept was transmitted to Japan alongside esoteric Buddhism,[e] and also practiced as rites in Onmyōdō during the Heian Period.[25][26]

Five dragons

[edit]- (Origins)

The idea of associating the five directions/regions (wufang; 五方) with the five colors is found in Confucian classic text,[28]

The Huainanzi (2nd cent. BC) describes the five colored dragons (azure/green, red, white, black, yellow) and their associations (Chapter 4: Terrestrial Forms),[29][30][31] as well as the placement of sacred beasts in the five directions (the Four Symbols beasts, dragon, tiger, bird, tortoise in the four cardinal directions and the yellow dragon.[27][32][33]

And the Luxuriant Dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals attributed to Dong Zhongshu (2nd cent. BC) describes the ritual involving five colored dragons.[34]

Attestations of Five Dragon Kings

[edit]Consecration Sutra

[edit]The apocryphal[19] Foshuo guanding jing (佛說灌頂經; "Consecration Sūtra Expounded by the Buddha" early 4th century, attributed to Po-Srimitra 帛尸梨蜜多羅), which purports to be Buddhist teachings but in fact incorporates elements of Chinese traditional belief,[35] associates five dragon kings with five colored dragons with five directions, as aforementioned.[18]

The text gives the personal names of the kings. To the east is the Blue Dragon Spirit King (青龍神王) named Axiuhe (阿修訶/阿脩訶), with 49 dragon kings under him, with 70 myriad myllion lesser dragons, mountain spirits, and assorted mei 魅 demons as minions. The thrust of this scripture is that in everywhere in every direction, there are the minions causing poisonings and ailments, and their lord the dragon kings must be beseeched in prayer to bring relief. In the south is the Red Dragon Spirit King named Natouhuati (那頭化提), in the west the White, called Helousachati (訶樓薩叉提/訶樓薩扠提), in the north the Black, called Nayetilou (那業提婁) and at center the Yellow, called Duluoboti (闍羅波提), with different numbers subordinate dragon kings, with minion hordes of lesser dragons and other beings.[17][36] Though connection of poison to rainmaking may not be obvious, it has been suggested that this poison-banishing sutra could have viably been read as a replacement in the execution of the ritual to pray for rain (shōugyōhō, 請雨経法), in Japan.[37] A medieval commentary (Ryūō-kōshiki, copied 1310) has reasoned that since the Great Peacock (Mahāmāyūrī) sūtra mandates one to chant dragon names in order to detoxify, so shall offerings made to dragon lead to "sweet rain".[38]

Divine Incantations Scripture

[edit]The wangfang ("five position") dragon kings are also attested in the Taishang dongyuan shenzhou jing (太上洞淵神咒經; "Most High Cavernous Abyss Divine Spells Scripture"[f]),[7] though not explicitly under the collective name of "five position dragon kings", but individually as "Eastern Direction's Blue Emperor Blue Dragon King (東方青帝青龍王)", and so forth.[39] It gives a laundry list of dragon kings by different names, stating that spells to cause rain can be performed by invoking dragon kings.[40]

Ritual process

[edit]An ancient procedural instruction for invoking five-colored dragons to conduct rainmaking rites occurs in the Luxuriant Dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals, under its "Seeking Rain" chapter (originally 2nd century B.C.). It prescribes earthenware figurines of greater and lesser dragons of a specific color according to season, namely blue-green, red, yellow, white, black, depending on whether it was spring, summer, late summer (jixia), autumn, or winter. And these figures were to be placed upon the alter at the assigned position/direction (east, south, center, west, or north).[41]

This Chinese folk rain ritual later became incorporated into Daoism.[40] The rituals were codified into Daoist scripture or Buddhist sūtras in the post-Later Han (Six Dynasties) period,[12] but Dragon King worship did not come into ascendancy until the Sui-Tang dynasties.[20] The rain rituals in Esoteric Buddhism in the Tang dynasty was actually an adaptation of indigenous Chinese dragon worship and rainmaking beliefs, rather than pure Buddhism.[40]

As a point of illustration, a comparison can be made against Buddhist procedures for rainmaking during the Tang dynasty. The rainmaking tract in the Collected Dhāraṇī Sūtras[g] (Book 11, under the chapter for "Rain Prayer Altar Method, qiyu tanfa; 祈雨壇法) prescribes an altar to be built, with mud figures of dragon kings placed on the four sides, and numerous mud-made lesser dragons arranged within and without the altar.[40][43]

Dragon Kings of the Four Seas

[edit]

Each one of the four Dragon Kings of the Four Seas (四海龍王 Sìhǎi Lóngwáng) is associated with a body of water corresponding to one of the four cardinal directions and natural boundaries of China:[3] the East Sea (corresponding to the East China Sea), the South Sea (corresponding to the South China Sea), the West Sea (Qinghai Lake), and the North Sea (Lake Baikal).

They appear in the classical novels like The Investiture of the Gods and Journey to the West, where each of them has a proper name, and they share the surname Ao (敖, meaning "playing" or "proud").

Dragon of the Eastern Sea

[edit]His proper name is Ao Guang (敖廣 or 敖光), and he is the patron of the East China Sea.

Dragon of the Western Sea

[edit]His proper names are Ao Run (敖閏), Ao Jun (敖君) or Ao Ji (敖吉). He is the patron of Qinghai Lake.

Dragon of the Southern Sea

[edit]He is the patron of the South China Sea and his proper name is Ao Qin (敖欽).

Dragon of the Northern Sea

[edit]His proper names are Ao Shun (敖順) or Ao Ming (敖明), and his body of water is Lake Baikal.

Japan

[edit]As already mentioned, Esoteric Buddhists in Japan who initially learned their trade from Tang dynasty China engaged in rainmaking ritual prayers invoking dragon kings under a system known as shōugyōhō or shōugyō [no] hō, established in the Shingon sect founded by the priest Kūkai, who learned Buddhism in Tang China. It was first performed by Kūkai in the year 824 at Shinsen'en, according to legend, but the first occasion probably took place historically in the year 875, then a second time in 891. The rain ritual came to be performed regularly.[44][45][46]

The shōugyōhō ritual used two mandalas that featured dragon kings. The Great Mandala that was hung up was of a design that centered around Sakyamuni Buddha, surrounded by the Eight Great Dragon Kings, the ten thousand dragon kings, Bodhisattvas (based on the Dayunlun qingyu jing 大雲輪請雨經, "Scripture of [Summoning] Great Clouds and Petitioning for Rain").[46][47][48] The other one was a "spread-out mandala”(shiki mandara 敷曼荼羅) laid flat out on its back, and depicted five dragon kings, which were one-, three-, five-, seven-, and nine-headed (based on the Collected Dhāraṇī Sūtras).[46]

Also, there was the "Five Dragons Festival/ritual" (Goryūsai. 五龍祭) that was performed by onmyōji or yin-yang masters.[26][49] The oldest mention of this in literature is from Fusō Ryakuki, the entry of Engi 2/902AD, 17th day of the 6th moon.[49] Sometimes, the performance of the rain ritual by Esoteric Buddhists (shōugyōhō) would be followed in succession by the Five Dragons Ritual from the Yin-Yang Bureau.[50] The Five Dragon rites performed by the onmyōji or yin yang masters had their heyday around the 10–11th centuries.[49] There are mokkan, or inscribed wooden tablets, used in these rites that have been unearthed (e.g., from an 8–10th century site and a 9th-century site).[51]

In Japan, there also developed a legend that the primordial being Banko (Pangu of Chinese myth) sired the Five Dragon Kings, who were invoked in the ritual texts or saimon read in Shinto or Onmyōdō rites, but the five beings later began to be seen less as monsters and more as wise princes.[52]

Worship of the Dragon God

[edit]Worship of the Dragon God is celebrated throughout China with sacrifices and processions during the fifth and sixth moons, and especially on the date of his birthday the thirteenth day of the sixth moon.[3] A folk religious movement of associations of good-doing in modern Hebei is primarily devoted to a generic Dragon God whose icon is a tablet with his name inscribed on it, utilized in a ritual known as the "movement of the Dragon Tablet".[53] The Dragon God is traditionally venerated with dragon boat racing.

In coastal regions of China, Korea, Vietnam, traditional legends and worshipping of whales (whale gods) have been referred to Dragon Kings after the arrival of Buddhism.[54]

Buddhism

[edit]Some Buddhist traditions describe a figure named Duo-luo-shi-qi or Talasikhin as a Dragon King who lives in a palace located in a pond near the legendary kingdom of Ketumati. It is said that during midnight he used to drizzle in this pond to cleanse himself of dust.[55]

Artistic depictions

[edit]- Longwang in art

-

The Dragon Kings of the Four Seas at the Grand Matsu Temple in Tainan.

-

The four Dragon Kings at the Temple of Mazu in Anping, Tainan.

See also

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ In a modern local ritual (cf. Changli County), the inscription reads "[...] Dragon King of the Four Seas, Five Lakes, Eight Rivers and Nine Streams (in sum, the lord of all the waters) [...]".[2]

- ^ Yellow Emperor is sometimes considered an incarnation of the Yellow dragon.[10]

- ^ The title gives wulong or five dragons, but the figure with a pair of hands growing out of eye socket is Yangjian taisui aka Yang Yin (Investiture of the Gods), and the other figures are the azure dragon, tiger, and vermillion bird from the Four Symbols.

- ^ Unique, as far as Monta is aware.[16] It gives the names of the for the dragon kings of the five colors and five directions.[17]

- ^ Cf. below on ritual practices.[clarification needed]

- ^ Or "The Most High Dongyuan Scripture of Divine Spells"

- ^ Translated by Atikūṭa 阿地瞿多.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Nikaido (2015), p. 54.

- ^ a b Overmyer (2009), p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tom (1989), p. 55.

- ^ Overmyer (2009), p. 21.

- ^ Naoe, Hiroji [in Japanese] (1980). Zhōngguó mínsúxué 中國民俗學. Lin Huaiqing 林懷卿 (tr.). Tainan: Shiyi Shuju. pp. 109–110.

- ^ Takeshi Suzuki (2007) "Ryūō shinkō 竜王信仰" Sekai daihyakkajiten, Heibonsha; 竜王信仰 Sekai daihyakkajiten, 2nd. ed., via Kotobank<

- ^ a b c Wang, Fang (2016). "6.2 Anlan Dragon King Temple: Not-in-Capital Palace of the Qing Dynasty". Geo-Architecture and Landscape in China's Geographic and Historic Context: Volume 2 Geo-Architecture Inhabiting the Universe. Springer. p. 211. ISBN 9789811004865.

- ^ a b Aratake, Kenichiro [in Japanese] (2012), Amakusa shotō no rekishi to genzai 天草諸島の歴史と現在, Institute for Cultural Interaction Studies, Kansai University, pp. 110–112, ISBN 9784990621339

- ^ Zhang (2014), p. 81 on Vietnamese custom; p. 53 on Lord Earth veneration with five dragon kings as ancillaries.

- ^ Fowler (2005), pp. 200–201.

- ^ Zhang (2014), p. 53.

- ^ a b c Monta (2012), p. 13.

- ^ Monta (2012), pp. 13–15.

- ^ Tan Chung (1998). "Chapter 15. A Sino-Indian Perspective for India-China Understanding". In Tan Chung; Thakur, Ravni (eds.). Across the Himalayan Gap: An Indian Quest for Understanding China. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts/Gyan Publishing House. p. 135. ISBN 9788121206174.

- ^ Lock, Graham; Linebarger, Gary S. (2018). "Orientation". Chinese Buddhist Texts: An Introductory Reader. Routledge. ISBN 9781317357940.

- ^ a b Monta (2012), p. 15.

- ^ a b c Yamaguchi, Kenji (2014-03-20). "Chūgoku minzokugaku Tō-dai onshin 'Gotei' kō: Mitama shinkō no genryū" 中國民俗學唐代瘟神「五帝」考―御霊信仰の源流―. The study of nonwritten cultural materials. 10: 225–225.

- ^ a b Monta (2012), pp. 13, 15.

- ^ a b c Sun, Wen (4 December 2019). "Texts and Ritual: Buddhist Scriptural Tradition of the Stūpa Cult and the Transformation of Stūpa Burial in the Chinese Buddhist Canon" (PDF). Religions. 10 (65). MDPI: 4–5. doi:10.3390/rel10120658.

- ^ a b c Zhang (2014), p. 44.

- ^ Doré, Henri [in French] (1917). Researches into Chinese Superstitions. First Part. Superstitious Practices. Vol. V. Translated by M. Kennelly; D. J. Finn; L. F. McGreat. Shanghai: T'usewei Printing Press. p. 682.

- ^ Zhang (2014), p. 45.

- ^ Faure (2005), pp. 76–77.

- ^ Anzhai shenzhou jing (安宅神咒經, "Sūtra of the divine formula for pacifying a house"). The spell invokes the white and black dragon kings, and three by name,[20] but the names don't really match those given by the Foshuo guanding jing.

- ^ Faure (2005), p. 72 (abstract); pp. 76–77: "the gods of the Five Directions, called the Five Dragons (goryū 五龍) or the Five Emperors (gotei 五帝). "

- ^ a b Drakakis, Athanathios (2010). "60. Onmōdō and Esoteric Buddhism". In Orzech, Charles; Sørensen, Henrik H.; Payne, Richard (eds.). Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. BRILL. p. 687. ISBN 9789004204010.

- ^ a b Monta (2012), pp. 13–14.

- ^ Rites of Zhou, "Chapter 6: Office of Winter" (2nd centudry BC).[27]

- ^ 劉安. (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- ^ Liu An (2010). "Terrestrial Forms 4.19". The Huainanzi. Translated by John S. Major; Sarah A. Queen; Andrew Seth Meyer; Harold D. Roth. Columbia University Press. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-0-231-52085-0.

- ^ Huang Fushan (2000). Dōnghàn chènwěi xué xīntàn 東漢讖緯學新探 [A New Probe into the Study of Prophecy and wefttext (chenwei) in the Eastern Han Dynasty]. Taiwan xuesheng shuju. p. 129. ISBN 9789571510033.

- ^ 劉安. (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

- ^ Liu An (2010). "Celestial Patterns 3.6". The Huainanzi. Translated by John S. Major; Sarah A. Queen; Andrew Seth Meyer; Harold D. Roth. Columbia University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-231-52085-0.

- ^ a b Monta (2012), p. 14.

- ^ Yamaguchi, citing the Daizōkyō zenkaisetsu daijiten: "[『仏説灌頂経』は]仏典ではあるが、 「中国の俗信仰的要素が認められる」(雄山閣『大蔵経全解説大事典』)".[17]

- ^ Higashi, Shigemi [in Japanese] (2006). Yamanoue-no-Okura no kenkyū 山上憶良の研究. Kanrin shobō. pp. 824–825. ISBN 9784877372309.

- ^ Trenson (2002), p. 468.

- ^ Ariga (2020), pp. 179–178.

- ^ . Taishang donyuan shenzhou jing 太上洞淵神呪經. Vol. 13 – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b c d Sakade (2010), pp. 61–65.

- ^ "... that is to say, canglong [blue-green dragon] to the east in spring, the red dragon tp the south in summer, the yellow dragon to the center in late summer (jìxià), white dragon to the west in autumn, and black dragon to the north in winter ..すなわち、春は蒼龍を東に、夏は赤龍を南に、季夏は黄龍を中央に、秋は白龍を西に、冬は黒龍を北にそれぞれ配置するとされている".[34]

- ^ Ariga (2020), p. 173.

- ^ Raiyu's edited work Hishō mondō 秘鈔問答 quotes from this sutra: "As the Collected Dhāraṇī Sūtras, 11 states, this altar should have a single-walled and four-gated boundary be made around its field. And on the East gate of the altar, the gate officer should be crafted out of mud, in the embodiment of the dragon king 其壇界畔作一重而開四門。壇之東門将以泥土作、龍王身".[42]

- ^ Trenson (2002), p. 455.

- ^ Trenson (2018), p. 276.

- ^ a b c Ariga (2020), pp. 175–174.

- ^ Iwata (1983) "Ch. 3 Goryūō kara gonin no ōji e第三章 五龍王から五人の王子へ", p. 125.

- ^ Trenson (2018), p. 277, n13, n14.

- ^ a b c Monta (2012), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Ruppert (2002), pp. 157–158.

- ^ Monta (2012), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Faure (2005), pp. 82–85.

- ^ Zhiya Hua (2013). Dragon's Name: A Folk Religion in a Village in South-Central Hebei Province. Shanghai People's Publishing House. ISBN 978-7208113299.

- ^ 李 善愛 (1999). "護る神から守られる神へ : 韓国とベトナムの鯨神信仰を中心に". 国立民族学博物館調査報告. 149: 195–212.

- ^ Ji Xianlin; Georges-Jean Pinault; Werner Winter (1998). Fragments of the Tocharian A Maitreyasamiti-Nataka of the Xinjiang Museum, China. De Gruyter. p. 15. ISBN 9783110816495.

Sources

[edit]- Ariga, Natsuki [in Japanese] (March 2020). "Kongō-ji zō 'Ryūō-kōshiki' no shikibun sekai: shakuronchūshaku to kiugirei wo megutte" 金剛寺蔵『龍王講式』の式文世界 : 釈論注釈と祈雨儀礼をめぐって [The study of Ryūō-kōshiki at Kongō-ji Temple : Consideration into the influence of Syakumakaenron and its commentaries and the rituals to pray]. Jinbun / Gakushuin University Research Institute for Humanities-journal. 18: 166–180. hdl:10959/00004813.

- Faure, Bernard R. (June 2005). "Pan Gu and his descendants: Chinese cosmology in medieval Japan" 盤古及其後代:論日本中古時代的中國宇宙論. Taiwan Journal of East Asian Studies. 2 (1): 71–88. doi:10.7916/D8V40THT. pdf @ National Taiwan Normal University

- Fowler, Jeanine D. (2005). An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism: Pathways to Immortality. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1845190866.[dead link]

- Iwata, Masaru [in Japanese] (1983). Kagura genryū kō 神楽源流考. Meicho shuppan.

- Monta, Seiichi [in Japanese] (2012-03-30), "Nihon kodai ni okeru gohōryū kankei shutsudo moji shiryō no shiteki haikei" 日本古代における五方龍関係出土文字史料の史的背景 (PDF), Bukkyō Daigaku Shūkyō Bunka Myūjiamu Kenkyūj Kiyō, 8

- Nikaido, Yoshihiro (2015). Asian Folk Religion and Cultural Interaction. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3847004851.

- Overmyer, Daniel L. (2009). Local Religion in North China in the Twentieth Century the Structure and Organization of Community Rituals and Beliefs (PDF). Leiden, South Holland; Boston, Massachusetts: Brill. ISBN 9789047429364. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-16. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- Ruppert, Brian O. (November 2002). "Buddhist Rainmaking in Early Japan: The Dragon King and the Ritual Careers of Esoteric Monks". History of Religions. 42 (2): 143–174. doi:10.1086/463701. JSTOR 3176409. S2CID 161794053.

- Sakade, Yoshinobu [in Japanese] (2010). Nihon to dōkyō bunka 日本と道教文化. Kadokawa shoten.

- Tom, K. S. (1989). Echoes from Old China: Life, Legends, and Lore of the Middle Kingdom. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0824812859. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- Trenson, Steven (2018). "Rice, Relics, and Jewels" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 35 (2): 269–308. JSTOR 26854486.

- Trenson, Steven (2002). "Une analyse critique de l'histoire du Shōugyōhō et du Kujakukyōhō : rites ésotériques de la pluie dans le Japon de l'époque de Heian" (PDF). Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie (in French). 13: 455–495. doi:10.3406/asie.2002.1191.

- Zhang Lishan (2014-03-31). Higashi ajia ni okeru Dokō shinkō to bunka kōshō 東アジアにおける土公信仰と文化交渉 (Thesis). Kansai University. doi:10.32286/00000236.

External links

[edit] Media related to Dragon King at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dragon King at Wikimedia Commons