Antonio de Espejo

Antonio de Espejo | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1540 |

| Died | 1585 (aged 45) |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | Explorer |

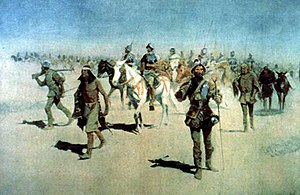

Antonio de Espejo (c. 1540–1585) was a Spanish explorer who led an expedition, accompanied by Diego Perez de Luxan, into what is now New Mexico and Arizona in 1582–83.[1][2] The expedition created interest in establishing a Spanish colony among the Pueblo Indians of the Rio Grande valley.

Life

[edit]

Espejo was born about 1540 in Cordova, Spain, and arrived in New Spain in 1571 along with the Chief Inquisitor, Pedro Moya de Contreras, who was sent by the Spanish king to establish an Inquisition. Espejo and his brother became ranchers on the northern frontier of New Spain. In 1581, Espejo and his brother were charged with murder. His brother was imprisoned and Espejo fled to Santa Barbara, Chihuahua, the northernmost outpost of New Spain. He was there when the Chamuscado-Rodriguez expedition returned from New Mexico.[3]

En route to New Mexico

[edit]Espejo, a wealthy man, assembled and financed an expedition for the ostensible purpose of ascertaining the fate of two priests who had remained behind with the Pueblos when Chamuscado led his soldiers back to the heartland of New Spain. Along with fourteen soldiers, a priest, about 30 indigenous servants and assistants, and 115 horses he departed from San Bartolome, near Santa Barbara, on November 10, 1582.[4]

Espejo followed the same route as Chamuscado and Rodriguez, down the Conchos River to its junction (La Junta) with the Rio Grande and then up the Rio Grande to the Pueblo villages.

Along the Conchos River, Espejo encountered the Conchos people who he described as "naked people ... who support themselves on fish, mesquite, mescal, and lechuguilla (agave)". Further downriver, he found Conchos who grew corn, squash, and melons. Leaving the Conchos behind, Espejo next encountered the Passaguates "who were naked like the Conchos" and seemed to have had a similar lifestyle. Next, Espejo came upon the Jobosos who were few in number, shy, and ran away from the Spaniards. All of these ethnic groups had previously been impacted by Spanish slave raids."[5]

Near the junction (La Junta) of the Conchos and the Rio Grande, Espejo entered the territory of the Patarabueyes who attacked his horses, killing three. Espejo succeeded in making peace with them. The Patarabueyes, he said, and the other people near La Junta were also called "Jumanos". -- the first use of the name for these people who would be prominent on the frontier for nearly two centuries. To add to the confusion, they were also called Otomoacos and Abriaches. Espejo saw five settlements of Jumanos with a population of about 10,000 people. They lived in low, flat-roofed houses and grew corn, squash, and beans and hunted and fished along the river. They gave Espejo well-tanned deer and bison skins. Leaving the Jumano behind, he passed through the lands of the Caguates or Suma, who spoke the same language as the Jumanos, and the Tanpachoas or Mansos. He found the Rio Grande Valley well populated all the way up to the present site of El Paso, Texas. Upstream from El Paso, the expedition traveled 15 days without seeing any people.[6]

The Pueblos

[edit]

In February 1583, Espejo arrived at the territory of the Piros, the most southerly of the Pueblo villagers. From there the Spanish continued up the Rio Grande. Espejo described the Pueblo villages as "clean and tidy". The houses were multi-storied and made of adobe bricks. "They make very fine tortillas," Espejo commented, and the Pueblos also served the Spanish turkeys, beans, corns, and pumpkins. The people "did not seem to be bellicose". The southernmost Pueblos had only clubs for weapons plus a few "poor Turkish bows and poorer arrows". Further north, the Indians were better armed and more aggressive. Some of the Pueblo towns were large, Espejo described Zia as having 1,000 houses and 4,000 men and boys. In their farming, the Pueblos used irrigation "with canals and dams, built as if by Spaniards". The only Spanish influence that Espejo noted among the Pueblos was their desire for iron. They would steal any iron article they could find.[7]

Espejo confirmed that the two priests had been killed by the Indians in the pueblo of Puala, near present-day Bernalillo. As the Spanish approached the Pueblo the inhabitants fled to the nearby mountains. The Spanish continued their explorations, east and west of the Rio Grande apparently with no opposition from the Indians. Near Acoma, they noted that a people called Querechos lived in the mountains nearby and traded with the townspeople. These Querechos were Navajo. The closely related Apache of the Great Plains during this period were also called Querechos.

Espejo also visited the Zuni and Hopi and heard stories of silver mines further west. With four men and Hopi guides he went in search of the mines, reaching the Verde River in Arizona, probably in the area of Montezuma Castle National Monument. He found the mines near present-day Jerome, Arizona, but was unimpressed by their potential. He heard from the local Indians, probably Yavapai, of a large river to the west, undoubtedly a reference to the Colorado.[8] Among the Hopi and the Zuni, Espejo met several Spanish-speaking Mexican Indians who had been left behind by, or escaped from, the Coronado expedition more than 40 years earlier.

The priest, several of the soldiers, and the Indian assistants decided, despite Espejo's entreaties, to return to Mexico.[9] It is possible that the priest was offended by the high-handed tactics of Espejo in dealing with the Pueblos. Espejo and eight soldiers stayed behind to look for silver and other precious metals. The little force had a skirmish with the Indians of Acoma Pueblo, apparently because two women slaves or prisoners of the Spanish escaped. The Spanish recaptured the women briefly, but they had to fight their way free. A Spanish soldier was wounded. In aiding the escape of the women, the Acomans and the Spanish exchanged volleys of harquebus fire, stones, and arrows. The Spanish, thus, were placed on notice that the hospitality of the Pueblos had limits. The Spanish then returned to the Rio Grande Valley where at a village they executed 16 Indians who mocked them and refused them food.[10]

The Spanish quickly departed the Rio Grande and explored eastward, journeying through the Galisteo Basin near the future city of Santa Fe and reaching the large pueblo at Pecos, called Ciquique.

Documenting the Expedition in New Mexico

[edit]When Antonio de Espejo set out to New Mexico as a relief for Chamuscado-Rodriguez, he left with many men including one man that would be vital in documenting the events that took place on the expedition. This man was Diego Perez de Luxan, he wrote journals about Espejo's findings in New Mexico and proved to be very important years later because of the rarity of documentation from the expedition. Diego was only on the expedition from 1582 - 1583.[11] In his journal, Diego wrote a detailed description of the terrain that Espejo and his crew explored throughout New Mexico. This includes mountains, the general path, pueblos, rivers, etc.[12]

Also in his journals, he wrote about some aspects of Indian culture through the Tigua who were located at the Rio Grande; Perez de Luxan wrote that the Tigua utilize masks in celebration and ceremonial use.[13] The first record of the names of six different pueblos a part of the Zuni nation and 5 different pueblos in Moqui were written in Luxan's journal.[14] Luxan described many interactions between the Spaniards and the pueblo people including gift giving, discovery of pueblos, reactions from the pueblo people upon Spaniard arrival, and conversations between the Indians and the Spaniards.[15]

Diego was only in Texas and New Mexico for 10 months, but his observations that he detailed in his journal, have been made useful by many historians as they have used it to make illustrations of what Texas and New Mexico used to look like, and the routes that Espejo's expedition took.[16] Diego Perez de Luxan has also been recognized as the first person to document certain landscapes, one being El Malpais. [17]

Return journey

[edit]Rather than return to the now unfriendly Rio Grande Valley, Espejo decided to return to Mexico via the Pecos River which he called "Rio de Las Vacas" because of the large number of bison the Spaniards encountered during the first six days they followed the river downstream. After descending the river about 300 miles from Ciquique the soldiers met Jumano Indians near Pecos, Texas, who guided them across country, up Toyah Creek, and cross country to La Junta. From here they followed the Conchos River upstream to San Bartolome, their starting place, arriving September 20, 1583. The priest and his companions had also returned safely.[18] Espejo was the first European to traverse most of the length of the Pecos River.

Espejo died in 1585 in Havana, Cuba. He was en route to Spain to attempt to get royal permission to establish a Spanish colony in New Mexico.[19] A chronicle of his expeditions was later published by Spanish historian and explorer Baltasar Obregón.

References

[edit]- ^ Antonio Espejo - Catholic Encyclopedia article

- ^ pg 189 - David Pike (2004). Roadside New Mexico (August 15, 2004 ed.). University of New Mexico Press. p. 440. ISBN 0-8263-3118-1.

- ^ Hammond, George P. and Rey, Agapito, The Rediscovery of New Mexico, 1580-1594. Albuquerque: U of NM Press, 1966, 16–17

- ^ Bolton, Herbert E. Spanish Exploration in the Southwest, 1542-1706. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916, 163–164; Riley, Carroll. Rio del Norte. Salt Lake City: U of Utah Press, 1995

- ^ Hammond and Rey, 155–160, 215–216

- ^ Hammond and Rey, 169, 216–220

- ^ Hammond and Rey, 172–182

- ^ Flint, Richard and Shirley Cushing, "Espejo Expedition" New Mexico Office of the State Historian http://www.newmexicohistory.org/filedetails.php?fileID=467 Archived 2010-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 4 Nov 2012

- ^ Flint, Richard and Flint, Shirley Cushing "Espejo Expedition," New Mexico Office of State Historian. http://www.newmexicohistory.org/filedetails.php?fileID=467 Archived 2010-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, accessed, Apr 1, 2010

- ^ Hammond and Rey, 201–204

- ^ Association, Texas State Historical. "Perez de Luxan, Diego". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Mecham, J. Lloyd (1926). "Antonio de Espejo and His Journey to New Mexico". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 30 (2): 114–138. ISSN 0038-478X.

- ^ Beals, Ralph L. (1932). "National Research Council Research Aid Fund". American Anthropologist. 34 (1): 165–169. ISSN 0002-7294.

- ^ Mecham, J. Lloyd (1926). "Antonio de Espejo and His Journey to New Mexico". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 30 (2): 114–138. ISSN 0038-478X.

- ^ Mecham, J. Lloyd (1926). "Antonio de Espejo and His Journey to New Mexico". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 30 (2): 114–138. ISSN 0038-478X.

- ^ Association, Texas State Historical. "Perez de Luxan, Diego". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ^ "El Malpais: In the Land of Frozen Fires (Chapter 2)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ^ Hammond and Rey, 229

- ^ Handbook of Texas Online, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fes03, accessed Apr 1, 2010