Antonio José Cavanilles

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (August 2014) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Antonio José Cavanilles | |

|---|---|

Statue of Cavanilles at the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid | |

| Born | 16 January 1745 Valencia, Spain |

| Died | 5 May 1804 (aged 59) Madrid, Spain |

| Known for | Taxonomy of Iberian, South American and Oceanian flora |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Botany |

| Academic advisors | Thouin, Jussieu |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Cav. |

Antonio José Cavanilles (16 January 1745 – 5 May 1804) was a leading Spanish taxonomic botanist, artist and one of the most important figures in the 18th century period of Enlightenment in Spain.

Cavanilles is most famous for his 2-volume book on Spanish flora, published in 1795 and titled ‘Observations on the Natural History, Geography and Agriculture of the Kingdom of Valencia’.He named many plants, particularly from Oceania. He named at least 100 genera, about 54 of which were still used in 2004, including Dahlia, Calycera, Cobaea, Galphimia, and Oleandra.[2] The standard author abbreviation Cav. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[3]

Biography

[edit]Cavanilles was born in Valencia. He lived in Paris from 1777 to 1781, where he followed careers as a clergyman and a botanist, thanks to André Thouin and Antoine Laurent de Jussieu. He was one of the first Spanish scientists to use the classification method invented by Carl Linnaeus.

Early life and education

[edit]Antonio José Cavanilles was born on January 16, 1745, in Valencia, Spain.

In his youth Cavanilles specialized in the study of mathematics and physics and obtained a doctorate in theology. Because he failed to secure the professorship to which he aspired, he accepted the post of guardian to the sons of the duke of Infantado and accompanied the duke to Paris in 1777.

Returning to Spain In 1789 he became fascinated with botany and took courses given by the renowned naturalists A. Laurent de Jussieu and Lamarck.

He studied at the University of Valencia, where he developed an interest in botany and natural history.

He published, in 1785, the first of ten monographs that constitute his Monadelphiae.

Botanical career

[edit]His return to Spain in 1789 marked the beginning of a rivalry with the director of the Madrid Botanical Gardens, Casimiro Gómez Ortega, and the botanist Hipólito Ruiz. In 1791 he was ordered to travel throughout the peninsula to study its botanical wealth; and, starting in 1799, he collaborated on the newly created Anales de histoaria natural.

Cavanilles became a professor of botany at the University of Valencia and later joined the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid, where he worked under the supervision of Casimiro Gómez Ortega. He succeeded Gómez Ortega as director of the botanical garden from 1801 to 1804.

The Spanish government ordered that any expeditions exploring Spanish America at that time send the Botanical Gardens examples of any herbs, seeds, and other plant forms that might be collected.

In 1804, Cavanilles was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia.[4]

Botanical Expeditions

Cavanilles led several botanical expeditions throughout Spain, collecting and cataloging numerous plant specimens. His explorations contributed significantly to the understanding of Spain's flora.

Artist and illustrator

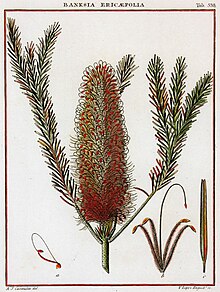

[edit]Cavanilles llustrated his own Icones et Descriptiones Plantarum (1791-1801).

Medical research

[edit]During his official research into Spanish flora (starting his journey in Valencia) that Cavanilles made significant contributions to the field of medicine.

Cavanilles identified the components of a popular Valencian remedy against rabies, after first checking its validity with the medical community. The positive results of this peer review gave rise to at least ten published articles in the ‘Annals of Natural Science’.

One more notable medical achievement was his identification of the rise in fatal diseases in regions which cultivated rice, due to the diversion of the water supply to the detriment of other areas which could more efficiently make use of this water for more important crops.

This resulted in local laws passed in Almenara (province of Castellón) to reduce the negative effects of rice paddies on the water supply and caused an immediate reduction in the local rate of fatal diseases.

Australia

[edit]The research carried out by Cavanilles documented over 600 species of plants from the Valencian region, as well as exotic species from expeditions made to Peru, Chile, the Philippines and Oceania.

Cavanilles described a number of Australian plants, including the genera Angophora and Bursaria, in his 6-volume Icones et Descriptiones Plantarum... (1791–1799). The Australian descriptions were based on collections made near Port Jackson and Botany Bay (New South Wales) by Luis Née (q.v.). Other Australian taxa were described in papers in Anal. Hist. Nat. 1: 89–107 (1799) & 3: 181–245 (1800). [5]

Taxonomic Work

Cavanilles is best known for his taxonomic work, particularly his contributions to the classification and description of plant species. He authored several botanical publications, including "Icones et Descriptiones Plantarum" in which 712 plants were listed according to the Linnaean classification and which gives data on some American plants and "Monadelphiae Classis Dissertationes Decem."

Mentorship

Cavanilles mentored several notable botanists, including Simón de Roxas Clemente y Rubio, Mariano Lagasca (1776– 1839) and José Celestino Mutis, who went on to make significant contributions to the field of botany in their own right.

Legacy

[edit]Cavanilles' work laid the foundation for modern botanical studies in Spain and had a lasting impact on the field of botany worldwide. His herbarium specimens and publications remain valuable resources for botanical research.

He died in Madrid in 1804.

Selected publications

[edit]- Icones et descriptiones plantarum, quae aut sponte in Hispania crescunt, aut in hortis hospitantur..., Madrid, 1791-1801 [1]

- Monadelphiae Classis Dissertationes Decem. (Paris, 1785; Madrid, 1790). [6]

- Observaciones sobre la historia natural, geografia, agricultura, población y frutos del reyno de Valencia, 2 vols. (Madrid, 1795–1797; new Zaragoza edition, 1958), a work in which he attempts to fix the natural wealth of the region studied. [7]

- Descripción de las plantas que Don A. J. Cavanilles demostró en las lecciones púhlicas del año 1801 (Madrid, 1803. 1804). [8]

- Ant. Iosephi Cavanilles Icones et descriptiones plantarum, quæ aut sponte in Hispania crescunt aut in hortis hospitantur. Madrid : Madrid Royal Printing, 1791. [9]

See also

[edit]- List of plants of Caatinga vegetation of Brazil

- List of plants of Cerrado vegetation of Brazil

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

References

[edit]- ^ W.Blunt & W.T. Stearn (1994). "The Art of Botanical Illustration 2nd edn".

- ^ Emilio LAGUNA LUMBRERAS (December 2004), "Sobre los géneros descritos por Cavanilles", Flora Montiberica, 28: 3–22

- ^ International Plant Names Index. Cav.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-04-01.

- ^ "Australian National Herbarium".

- ^ Stafleu, F. A., & Cowan, R. S. (1981). Taxonomic literature: A selective guide to botanical publications and collections with dates, commentaries and types (Vol. 2). Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Luis Valdés Cavanilles (1946). Archivo del ilustre botánico D. Antonio Joseph Cavanilles. Madrid: D. Antonio Joseph Cavanilles.

- ^ E. Alvarez López. "Antonio José Cavanilles". Anales del Jardin botánico de Madrid. 6 (pt. 1 (1946)): 1–64.

- ^ Antonio José Cavanilles y Palop. "Images and Descriptions of the Plants that Grow Spontaneously in Spain or Are Hosted in Gardens by Antonio José Cavanilles". Library of Congress.

Further reading

[edit]- "Cavanilles, Antonio José (Joseph) (1745-1804". JSTOR Global Plants. ITHAKA. 2013.

- Cavanilles, Antonio José (1745–1804). Australian National Herbarium.

- Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment. Daniela Bleichmar. October 2012.https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226058559.003.0002

- The Botany of Empire in the Long Eighteenth Century. by S Easterby-Smith · 2017. [1]

- Descripcion De Las Plantas Que D. Antonio Josef Cavanilles Demostró En Las Lecciones Públicas Del Año 1801: Precedida De Los Principios Elementales De La Botánica; Volume 1. [2]

External links

[edit]- Biography by the Australian National Botanic Gardens

- Malpighiaceae/Cavanilles

- Monadelphiæ classis dissertationes decem on the Internet Archive

- Chronophobia Scans of 160 plates from Monadelphiæ classis dissertationes decem

- Antonio José Cavanilles. Polymath Virtual Library, Fundación Ignacio Larramendi

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. "Antonio José Cavanilles (1745–1804).

- Cavanilles, Antonio José. Encyclopedia.com.

- Cavanilles and the Flora of the Kingdom of Valencia