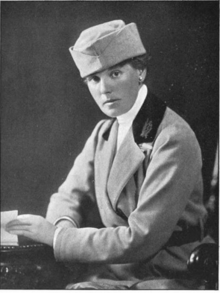

Louise McIlroy

Louise McIlroy | |

|---|---|

Louise McIlroy | |

| Born | Anne Louise McIlroy 11 November 1874 Lavin House, County Antrim, Ireland |

| Died | 8 February 1968 (aged 93) Turnberry, Ayrshire, Scotland |

| Education | MB ChB (1898), MD (1900), DSc (1910) University of Glasgow LM (1901) Dublin |

| Known for | Consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist first woman awarded Doctor of Medicine from the University of Glasgow first woman medical professor in the United Kingdom |

| Medical career | |

| Sub-specialties | obstetrics and gynaecology |

| Awards | Croix de Guerre (1916) Médaille des Epidemies Order of St. Sava Serbian Red Cross Medal OBE (1920) Dame (1927) FRCP DSc LLD (Glasgow) |

Dame Anne Louise McIlroy DBE FRCOG (11 November 1874 – 8 February 1968), known as Louise McIlroy, was a distinguished and honoured Irish-born British physician, specialising in obstetrics and gynaecology. She was both the first woman to be awarded a Doctor of Medicine (MD) degree and to register as a research student at the University of Glasgow.[1][2] She was also the first woman medical professor in the United Kingdom.[3]

Early life and education

[edit]McIlroy was born on 11 November 1874 at Lavin House, County Antrim (present-day Northern Ireland). Her father, James, was a general practitioner at Ballycastle. In 1894 she matriculated at the University of Glasgow to study medicine and obtained her MB ChB in 1898. In 1900 she received her MD with commendation. During her studies she won class prizes in both medicine and pathology.[1][2][3]

Career

[edit]Her postgraduate work took her throughout Europe where she further specialised in gynaecology and obstetrics, becoming a Licentiate of Midwifery in Ireland in 1901. Her first position was as a house surgeon at the Samaritan Hospital For Women in Glasgow in 1900, followed by Gynaecological Surgeon at the Victoria Infirmary in Glasgow from 1906 to 1910. She continued her studies, gaining a DSc from the University of Glasgow in 1910. In 1911 she took up the position of First Assistant to Professor J. M. Munro Kerr, who held the Muirhead Chair of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the university.[1][2]

At the outbreak of the First World War she and other women medical graduates offered their services to the government. They were declined as "the battlefield .. [was] no place for women". They decided to set up the Scottish Women's Hospital for Foreign Service. She commanded the Girton and Newnham unit of the hospital at Domaine de Chanteloup, Sainte-Savine, near Troyes, France before being posted to Serbia and, three years later, Salonika.[4][5]

During her time in Salonika she established a nurses training school for Serbian girls and oversaw the establishment of the only orthopaedic centre in the Eastern Army. She finished her war service as a surgeon at a Royal Army Medical Corps hospital in Constantinople.[1]

In 1921, she was appointed to the Royal Free Hospital in London as consultant in obstetrics and gynaecology. She was the first woman Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the London School of Medicine for Women, becoming the first woman to be appointed a medical professor in the United Kingdom.[1]

On 7 July 1921, McIlroy delivered a paper at the Medico-Legal Society in London. In it, she said that the "most harmful method [of contraception] of which I have experience is the use of the pessary".[6] Dr Halliday Sutherland heard her talk and he later quoted her in his 1922 book "Birth Control". When Marie Stopes sued Dr Sutherland for libel over remarks in the book, McIlroy because a witness for the defence.[7]

She retired in 1934, in her own words 'to gain a few years of freedom'[3] although she continued private practice at Harley Street and other hospitals and clinics throughout London. At the outbreak of the Second World War she came out of semi-retirement to work as a consultant for the maternity service at Buckinghamshire County Council. She was also the senior obstetrician to the Maternity Hospital for the Wives of Officers, Fulmer Chase.[3]

She was active in several professional medical associations: her interest in medical legal matters culminated in her becoming President of the Medico-Legal Society of London; at the British Medical Association (BMA) she was vice-president of the Section of Obstetrics and Gynaecology in 1922, 1930 and 1932; a member of the Representative Body from 1936 to 1939; a member of the BMA Council from 1938 to 1943, President of the BMA Metropolitan Counties Branch in 1946 and she was also president of the Section of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the Royal Society of Medicine.[3]

Publications

[edit]Throughout her career McIlroy wrote many articles in journals such as The Lancet, the British Medical Journal and The Practitioner, gave lectures and presented papers at conferences. Her particular interest was pre-eclampsia, pain relief during childbirth, managing asphyxia in newborn babies and social issues.[3] She authored and co-authored several books including;[1]

- From a Balcony on the Bosphorus (1924)[1][8]

- Anaesthesia and analgesia in labour - with Katharine G. Lloyd-Williams (1934)[9]

- The Toxaemias of Pregnancy (1936)[10]

Honours

[edit]For her work during the First World War McIlroy was awarded the Croix de Guerre in 1916,[1][2] the Médaille des Epidemies, the Serbian Order of St. Sava and the Serbian Red Cross Medal.[2]

She was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire on 30 March 1920[11] for her services to medicine and in 1929 she was promoted to Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire.[1]

She was elected as a Foundation Fellow to the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.[3]

In 1932 she became a Member of the Royal College of Physicians and was elected as a Fellow in 1937.[1]

She received several honorary degrees including a DSc from Belfast of which she was particularly proud.[1][3]

She was an Honorary Fellow of the Liverpool Medical Institution.[3]

Later life

[edit]After the Second World War she returned to her retirement and left London to live with her sister, Dr Janie McIlroy, in Turnberry, Ayrshire, Scotland.[3] She died in the Glasgow Hospital on 8 February 1968, aged 93. She never married.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Pitt, Susan J. (2010). "Louise McIlroy". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/47540. Retrieved 28 March 2016. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e "Dame Anne Louise McIlroy profile". The University of Glasgow story. Glasgow: The University of Glasgow. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Munks Roll details for Anne Louise (Dame) McIlroy". Royal College of Physicians. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ "University of Glasgow :: Story :: Biography of Surgeon Anne Louise McIlroy". www.universitystory.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "SCOTTISH WOMEN'S HOSPITALS".

- ^ "Marie Stopes and the Sexual Revolution" by June Rose. Faber and Faber, London. 1993. Page 153.

- ^ "The Trial of Marie Stopes" (Muriel Box, ed.), Femina Books Ltd, 1967. pg. 210.

- ^ McIlroy, A. Louise (1 January 1924). From a balcony on the Bosphorus. London; New York: Country Life; C. Scribners Sons. OCLC 7242202.

- ^ Lloyd-Williams, Katharine G; McIlroy, Louise (1 January 1934). Anaesthesia and analgesia in labour. Baltimore: W. Wood. OCLC 13454386.

- ^ McIlroy, Louise (1 January 1936). The toxaemias of pregnancy. London, UK: Arnold. OCLC 14753058.

- ^ "No. 31840". The London Gazette (Supplement). 26 March 1920. p. 3795.

Sources

[edit]- The Lancet, Vol. 1 (1968), p. 429.

- British Medical Journal, Vol. 1 (1968), p. 451.

External links

[edit] Media related to Louise McIlroy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Louise McIlroy at Wikimedia Commons

- 1874 births

- 1968 deaths

- Alumni of the University of Glasgow

- 20th-century British medical doctors

- British people of World War I

- British people of Irish descent

- Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians

- Recipients of the Order of St. Sava

- British recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France)

- People from Ballycastle, County Antrim

- 20th-century British women medical doctors

- Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service volunteers

- British obstetricians

- British gynaecologists