Ampelmännchen

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (August 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

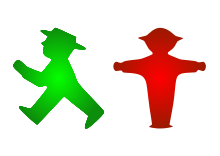

Ampelmännchen (German: [ˈampl̩ˌmɛnçən] ; literally 'little traffic light man', diminutive of Ampelmann [ampl̩ˈman] ) is the symbol shown on pedestrian signals in Germany. Prior to German reunification in 1990, the two German states had different forms for the Ampelmännchen, with a generic human figure in West Germany, and a generally "male" figure wearing a hat in the East.

The Ampelmännchen is a beloved symbol in former East Germany,[1] "enjoy[ing] the privileged status of being one of the few features of East Germany to have survived the end of the Iron Curtain with his popularity unscathed".[2] After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Ampelmännchen acquired cult status and became a popular souvenir item in the tourism business.[1]

Concept and design

[edit]

The first traffic lights at pedestrian crossings were erected in the 1950s, and many countries developed different designs (which were eventually standardised).[3] At that time, traffic lights were the same for cars, bicycles and pedestrians.[4] The East Berlin Ampelmännchen was created in 1961 by traffic psychologist Karl Peglau (1927–2009) as part of a proposal for a new traffic lights layout. Peglau criticised the fact that the standard colours of the traffic lights (red, yellow, green) did not provide for road users who were unable to differentiate between colours (ten percent of the total population), and that the lights themselves were too small and too weak when competing against luminous advertising and sunlight. Peglau proposed retaining the three colours while introducing intuitive shapes for each coloured light. This idea received strong support from many sides, but Peglau's plans were doomed by the high costs involved in replacing existing traffic light infrastructure.[5]

Unlike motor traffic, pedestrian traffic has no constraints on age or health (physical or mental), and therefore must accommodate children, elderly people and the disabled. Peglau therefore resorted to images of a little man, his body forming shapes to indicate the appropriate action: The thick, outstretched arms of the front-facing red man form a pictorial barricade to signal "stop", while the sideways-facing green man with his pacing legs forms an arrow, signalling permission to "go ahead". The yellow light was abandoned because of the generally unhurried nature of pedestrian traffic.[5]

Peglau's secretary Anneliese Wegner drew the Ampelmännchen per his suggestions. The initial concept envisioned the Ampelmännchen to have fingers, but this idea was dropped due to technical difficulties with the illumination. However, the man's "perky", "cheerful" and potentially "petit bourgeois" hat – inspired by a summer photo of Erich Honecker in a straw hat[6] – was retained, to Peglau's surprise. The prototypes of the Ampelmännchen traffic lights were built at the VEB-Leuchtenbau Berlin.[5]

The Ampelmännchen was officially introduced on 13 October 1961 in Berlin, at which time the media attention and public interest focused on the new traffic lights, not the symbols.[5] The first Ampelmännchen were produced as cheap decals. Beginning in 1973, the Ampelmännchen traffic lights were produced at VEB Signaltechnik Wildenfels and privately owned artisan shops.[7]

Decades later, Daniel Meuren of the weekly German newsmagazine Der Spiegel described the Ampelmännchen as uniting "beauty with efficiency, charm with utility, [and] sociability with fulfilment of duties".[8] The Ampelmännchen reminded others of a childlike figure with big head and short legs, or a religious leader.[9]

The Ampelmännchen proved so popular that it became part of road safety education for children in the early 1980s.[5] The East German Ministry of the Interior had the idea to bring the two traffic light figures to life as speaking characters. The Ampelmännchen were introduced with much media publicity. They appeared in strip cartoons, also in situations without traffic lights. The red Ampelmännchen appeared in potentially dangerous environments, and the green Ampelmännchen gave advice. Together with the Junge Welt publishing company, games with the Ampelmännchen were developed. Ampelmännchen stories were developed for radio broadcasts.[10] Partly animated Ampelmännchen stories with the name Stiefelchen und Kompaßkalle were broadcast once a month as part of the East German children's bedtime television programme Sandmännchen, which had one of the largest viewing audiences in East Germany.[11] The animated Ampelmännchen stories raised international interest, and the Czech festival for road safety education films awarded Stiefelchen und Kompaßkalle the Special Award by the Jury and the Main Prize for Overall Accomplishments in 1984.[11]

History after reunification

[edit]Following the German reunification in 1990, there were attempts to standardise all traffic signs to the West German forms. East German street signs and traffic signs were dismantled and replaced because of differing fonts in the former two German countries.[12] The East German education programmes featuring the Ampelmännchen vanished. This led to calls to save the East German Ampelmännchen as a part of the East German culture.[1][2] The first solidarity campaigns for the Ampelmännchen took place in Berlin in early 1995.

Markus Heckhausen, a graphic designer from the West German city of Tübingen and founder of Ampelmann GmbH in Berlin,[1] had first noticed the Ampelmännchen during his visits to East Berlin in the 1980s. When he was looking for new design possibilities in 1995, he had the idea to collect dismantled Ampelmännchen and build lamps. But he had difficulty finding old Ampelmännchen and eventually contacted the former VEB Signaltechnik (now Signaltechnik Roßberg GmbH) regarding their excess stock. The company was still producing Ampelmännchen, and liked Heckhausen's marketing ideas. The public embraced Heckhausen's first six lamp models. Local newspapers published full-page articles, followed by articles in national newspapers and designer magazines. The successful German daily soap opera Gute Zeiten, schlechte Zeiten used the Ampelmännchen lamp in their coffeehouse set.[9] Designer Karl Peglau explained the public reaction in 1997:

It is presumably their special, almost indescribable aura of human snugness and warmth, when humans are comfortably touched by this traffic symbol figure and find a piece of honest historical identification, giving the Ampelmännchen the right to represent a positive aspect of a failed social order.[13]

The Ampelmännchen became a virtual mascot for the East German nostalgia movement, known as Ostalgie.[2] The protests were successful, and the Ampelmännchen returned to pedestrian crossings. They can now also be seen in some western districts of Berlin.[4] Some western German cities such as Saarbrücken[14] and Heidelberg[15] have since adopted the design for some intersections. Peter Becker, marshal of Saarbrücken, explained that lights of the East German Ampelmännchen have greater signal strength than West German traffic lights, and "in our experience people react better to the East German Ampelmännchen than the West German ones."[14] In Heidelberg, however, a government department asked the city to stop the installation of more East German Ampelmännchen, citing standards in road traffic regulations.[15]

Heckhausen continued to incorporate the Ampelmännchen design into products and had an assortment of over forty Ampelmännchen souvenir products in 2004, reportedly earning €2 million yearly. In the meantime, east German businessman Joachim Rossberg had also used the distinctive traffic symbol as a logo, and claimed to make €50,000 per year from merchandise. Heckhausen appealed to a Leipzig court in 2005 over the marketing rights, suing Rossberg for failing at making full use of his marketing rights; German legislature rules state that if no use of marketing rights is made for five years, the rights can be cancelled. The court ruled in 2006 that Rossberg's right to use the Ampelmännchen as a marketing brand had largely lapsed and had passed back into the public domain. Rossberg only retained the right to use the symbol to market liqueur, and may no longer use the logo on beer and T-shirts. The court case was later seen by some as part of the cultural and political struggle between residents of the two parts of the reunified country, in which the underdog East generally lost.[1][2]

Berlin started to modernize its traffic lights from using regular light bulbs to LED technology in early 2006, which promised better visibility and lower maintenance costs.[16]

-

Pan-German Ampelmännchen in Chemnitz

-

Ampelmännchen in Berlin

-

Tourist souvenirs featuring the East German traffic lights

-

Explanations for the Ampelmann at a shop in Hagi, Japan

Variations

[edit]There are three Ampelmännchen variations in modern-day Germany – the old East German version, the old West German version, and the pan-German Ampelmännchen introduced in 1992. Each German state holds the right to determine the version used.[17] East Germans have changed the look of Ampelmännchen traffic lights as a joke since the early 1980s; this turned into media-effective efforts to call attention to the vanishing East German Ampelmännchen in the 1990s.[18] The Ampelmännchen on several traffic lights in Erfurt were changed by modifying the template, showing Ampelmännchen carrying backpacks or cameras.[15]

In 2004, Joachim Rossberg invented the female counterpart to the Ampelmännchen, the Ampelfrau, which was installed on some traffic lights in Zwickau,[19] Dresden[20] and Fürstenwalde.[21] The Ampelfrau also appears at some traffic lights in Reykjavik, Iceland.[22]

In 2019, Fulda, a strongly Catholic city in Hesse, adopted Ampelmännchen designed to look like Saint Boniface, on the occasion of 1275th anniversary of the foundation of Fulda princely abbey.[23]

Art collective Ztohoven

[edit]Roman Tic (a pseudonym playing with "romantic") of the art collective Ztohoven ("(The way) Out of shit") changed some pedestrian traffic lights in the daylight hours of 8 April 2007 in five hours work, with a ladder and wearing red overalls. He used different motifs, including men and women (e.g. drinking, urinating).[24][25][26][27]

Inclusive traffic lights

[edit]On 11 May 2015, before the Life Ball and the Eurovision Song Contest in Vienna, the city changed some traffic lights to "Ampelpärchen"; these are designs with homo- and heterosexual couples, hugging or holding hands. In June 2015, Salzburg (at Staatsbrücke) and Linz (at Mozartkreuzung) followed suit with the same designs. However, in December 2015, a city traffic minister of the party FPÖ dismounted the privately sponsored faceplates, deeming them unnecessary.[28][29][30][31]

-

The Ampelfrau

-

Ampelmännchen with umbrella

-

Ampelmännchen with bicycle

-

Ampelmännchen as warning light

Tribute

[edit]On 13 October 2017, Google celebrated the 56th anniversary of the Traffic Light Man with a Google Doodle.[32]

See also

[edit]- Xiaolüren, an animated traffic light system in Taiwan

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "East German Loses Copyright Battle over Beloved Traffic Symbol". Deutsche Welle. 17 June 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Ampelmännchen is Still Going Places". Deutsche Welle. 16 June 2005. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ^ Heckhausen, Markus (1997). "Die Entstehung der Lichtzeichenanlage". Das Buch vom Ampelmännchen. pp. 15–17.

- ^ a b Jacobs, Stefan (26 April 2005). "Ein Männchen sieht rot". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Peglau, Karl (1997). "Das Ampelmännchen oder: Kleine östliche Verkehrsgeschichte". Das Buch vom Ampelmännchen. pp. 20–27.

- ^ "East Germany's iconic traffic man turns 50". The Local. 13 October 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ^ Roßberg, Joachim (1997). "Vom VEB zur GmbH". Das Buch vom Ampelmännchen. pp. 42–44.

- ^ Meuren, Daniel (26 September 2001). "Die rot-grüne Koalition". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 6 February 2009.

Das 40 Jahre alte Ampelmännchen sozialistischer Prägung verbindet Schönheit mit Effizienz, Charme mit Zweckmäßigkeit, Gemütlichkeit mit Pflichterfüllung.

- ^ a b Heckhausen, Markus (1997). "Ampelmännchen im zweiten Frühling". Das Buch vom Ampelmännchen. pp. 52–57.

- ^ Vierjahn, Margarethe (1997). "Verkehrserziehung für Kinder". Das Buch vom Ampelmännchen (in German). pp. 28–30.

- ^ a b Rochow, Friedrich (1997). "Stiefelchen und Kompaßkalle". Das Buch vom Ampelmännchen. pp. 32–41.

- ^ Gillen, Eckhart (1997). Das Buch vom Ampelmännchen. p. 48.

- ^ Peglau, Karl (1997). "Das Ampelmännchen oder: Kleine östliche Verkehrsgeschichte". Das Buch vom Ampelmännchen (in German). p. 27.

Vermutlich liegt es an ihrem besonderen, einer Beschreibung kaum zugänglichen Fluidum von menschlicher Gemütlichkeit und Wärme, wenn sich Menschen von dieser Symbolfiguren der Straße angenehm berührt und angesprochen fühlen und darin ein Stück ehrlicher historischer Identifikation finden, was den Ampelmännchen das Recht zur Repräsentation der positiven Aspekte einer gescheiterten Gesellschaftsordnung gibt.

- ^ a b Bolzenius, Theodor (23 May 2006). "Polizisten flitzen mit Segways durch die Kirchenmeile" (in German). katholikentag.net. Retrieved 11 December 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c "Deutschland wächst zusammen – Ampelmännchen und Grüner Pfeil". Politik und Unterricht (in German) (2/2000). 2000. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ^ Lemmer, Christoph (8 May 2006). "Ampelmännchen privat". Der Tagesspiegel. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ^ "Heimliches Wappen der DDR". Der Spiegel (in German). No. 2/1997. 6 January 1997. p. 92.

- ^ König, Maria (1997). "Die Gallier aus Thüringen". Das Buch vom Ampelmännchen. pp. 46–47.

- ^ "Grünes Licht für Ampelfrau". Der Spiegel (in German). 23 November 2004. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ^ "Markenrechte an Ampelfrau beschäftigen die Justiz" (in German). Berliner Morgenpost. 23 April 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ^ "Hats off as "Ampelfrau" helps Germans cross the road". Reuters. 7 March 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "akg-images - Search Result". www.akg-images.de. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Bonifatius als Ampelmännchen – neue Lichtzeichen leiten Fußgänger im Dom-Viertel". www.fuldaerzeitung.de (in German). 20 April 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BksSF4oQe4Y Portrait: Prager Kollektiv Ztohoven - Part 1 - arte Tracks vom 31 March 2011; Tom Klim, 6 April 2011, youtube.com, Video 6:53. Retrieved 16 May 2015

- ^ Sabotage in Prag – Ampelmann mit Pulle. auf: sueddeutsche.de, 11 April 2007

- ^ Hans-Jörg Schmidt: Urinierende Ampelmännchen – Künstler verurteilt. auf: Welt Online. 6 December 2011

- ^ [1] sidewalkCINEMA 2007, film.at, 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ ""Lockeres Statement": Ampelpärchen gibt es jetzt auch in Salzburg" (in German). Kronen Zeitung. 18 June 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ http://ooe.orf.at/news/stories/2718342/ Ampelpärchen leuchten jetzt auch in Linz, orf.at 26 June 2015, retrieved 7 December 2015. (German)

- ^ http://www.krone.at/Oesterreich/Linzer_FPOe-Stadtrat_liess_Ampelpaerchen_abmontieren-Voellig_unnoetig-Story-485830 "völlig unnötig": Linzer FPÖ-Stadtrat liess Ampelpärchen abmontieren, krone.at 7 December 2015, retrieved 7 December 2015. (German)

- ^ http://ooe.orf.at/news/stories/2746216/ FPÖ-Stadtrat liess Ampelpärchen abmontieren, orf.at 7 December 2015, retrieved 7 December 2015. (German)

- ^ "56th Anniversary of the Traffic Light Man". Google. 13 October 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Heckhausen, Markus, ed. (1997). Das Buch vom Ampelmännchen (in German). Eulenspiegel Verlag. ISBN 3-359-00910-X.

External links

[edit]- Original Ampelmann Company which manufactured them originally

- Ampelmann at ampelmann.de