Amos 'n' Andy

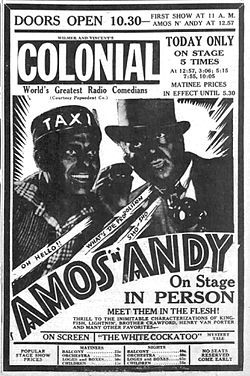

A 1935 advertisement for the entertainment duo Amos 'n' Andy. | |

| Other names | The Amos 'n' Andy Show 1943–1955 Amos 'n' Andy's Music Hall 1955–1960 |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | United States |

| Language(s) | English |

| Home station | WMAQ 670 AM Chicago NBC Radio CBS Radio and Television |

| TV adaptations | The Amos 'n' Andy Show 1951–1953 |

| Starring | |

| Announcer | Bill Hay[1] Del Sharbutt[2] Harlow Wilcox Carleton KaDell Art Gilmore John Lake Ken Carpenter Ken Niles[3] |

| Created by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Original release | March 19, 1928 – November 25, 1960 |

| Opening theme | "The Perfect Song" |

| Sponsored by | Pepsodent Toothpaste Campbell's Soup Rinso Rexall Drugs |

Amos 'n' Andy was an American radio sitcom about black characters, initially set in Chicago then later in the Harlem section of New York City. While the show had a brief life on 1950s television with black actors, the 1928 to 1960 radio show was created, written and voiced by two white actors, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, who played Amos Jones (Gosden) and Andrew Hogg Brown (Correll), as well as incidental characters. On television from 1951–1953, black actors took over the majority of the roles; white characters were infrequent.

Amos 'n' Andy began as one of the first radio comedy series and originated from station WMAQ in Chicago. After the first broadcast in 1928, the show became a hugely popular series, first on NBC Radio and later on CBS Radio and Television. Later episodes were broadcast from the El Mirador Hotel in Palm Springs, California.[4]: 168–71 The show ran as a nightly radio serial (1928–43), as a weekly situation comedy (1943–55) and as a nightly disc-jockey program (1954–60). A television adaptation ran on CBS (1951–53) and continued in syndicated reruns (1954–66). It was not shown to a nationwide audience again until 2012.[5]

Origins

[edit]

Gosden and Correll were white actors familiar with minstrel traditions. They met in Durham, North Carolina[6][7] in 1920. Both men had some scattered experience in radio, but it was not until 1925 that the two appeared on Chicago's WQJ. Their appearances soon led to a regular schedule on another Chicago radio station, WEBH, where their only compensation was a free meal.[8] The pair hoped that the radio exposure would lead to stage work; they were able to sell some of their scripts to local bandleader Paul Ash,[9] which led to jobs at the Chicago Tribune's station WGN in 1925. This lucrative offer enabled them to become full-time broadcasters. The Victor Talking Machine Company also offered them a recording contract.[8]

Since the Tribune syndicated Sidney Smith's popular comic strip The Gumps, which had successfully introduced the concept of daily continuity, WGN executive Ben McCanna thought a serialized version would work on radio. He suggested that Gosden and Correll adapt The Gumps for radio. The idea seemed to involve more risk than either Gosden or Correll was willing to take; neither was adept at imitating female voices, which would have been necessary for The Gumps. They were also conscious of having made names for themselves with their previous act. By playing the roles of characters using minstrel dialect, they would be able to conceal their identities enough to be able to return to their old pattern of entertaining if the radio show proved to be a failure.[8]

Instead, they proposed a series about "a couple of colored characters" that borrowed certain elements from The Gumps. Their new show, Sam 'n' Henry,[10] began on January 12, 1926 and fascinated radio listeners throughout the Midwestern United States.[11] It became so popular that in 1927 Gosden and Correll requested that it be distributed to other stations on phonograph records in a "chainless chain" concept that would have been the first radio syndication. When WGN rejected the proposal, Gosden and Correll quit the show and the station; their last musical program for WGN was announced in the Chicago Daily Tribune on January 29, 1928.[12] Episodes of Sam 'n' Henry continued to air until July 14, 1928.[13] Correll's and Gosden's characters contractually belonged to WGN, so the pair was unable to use the characters' names when performing in personal appearances after leaving the station.[5][8]

WMAQ, the Chicago Daily News station, hired Gosden and Correll and their former WGN announcer Bill Hay to create a series similar to Sam 'n' Henry. It offered higher salaries than WGN as well as the right to pursue the syndication idea.[14] The creators later said that they named the characters Amos and Andy after hearing two elderly African-Americans greet each other by those names in a Chicago elevator.[6] Amos 'n' Andy began on March 19, 1928[15] on WMAQ, and prior to airing each program, Gosden and Correll recorded their show on 78-rpm discs at Marsh Laboratories, operated by electrical recording pioneer Orlando R. Marsh.[16] Early 1930s broadcasts of the show originated from the El Mirador Hotel in Palm Springs, California.[17]

For the program's entire run as a nightly series in its first decade, Gosden and Correll provided over 170 male voice characterizations. With the episodic drama and suspense heightened by cliffhanger endings, Amos 'n' Andy reached an ever-expanding radio audience. It was the first radio program to be distributed by syndication in the United States, and by the end of the syndicated run in August 1929, at least 70 other stations carried recorded episodes.[8]

Early storylines and characters

[edit]Amos Jones and Andy Brown worked on a farm near Atlanta, Georgia, and during the first week's episodes, they made plans to find a better life in Chicago, despite warnings from a friend. With four ham-and-cheese sandwiches and $24, they bought train tickets and headed for Chicago, where they lived in a rooming house on State Street and experienced some rough times before launching their own business, the Fresh Air Taxi Company.[8] (The first car they acquired had no windshield; the pair turned it into a selling point.) By 1930, the noted toy maker Louis Marx and Company was offering a tin wind-up version of the auto, with Amos and Andy inside.[18] The toy company produced a special autographed version of the toy as gifts for American leaders, including Herbert Hoover.[19] There was also a book, All About Amos 'n' Andy and Their Creators, in 1929 by Correll and Gosden (reprinted in 2007 and 2008),[20][21] and a comic strip in the Chicago Daily News.[10]

Naïve but honest Amos was hardworking, and, after his marriage to Ruby Taylor in 1935, also a dedicated family man. Andy was a gullible dreamer with overinflated self-confidence who tended to let Amos do most of the work. Their Mystic Knights of the Sea lodge[22] leader, George "Kingfish" Stevens, would often lure them into get-rich-quick schemes or trick them into some kind of trouble. Other characters included John Augustus "Brother" Crawford, an industrious but long-suffering family man; Henry Van Porter, a social-climbing real estate and insurance salesman; Frederick Montgomery Gwindell, a hard-charging newspaperman; Algonquin J. Calhoun, a somewhat crooked lawyer added to the series in 1949, six years after its conversion to a half-hour situation comedy; William Lewis Taylor, Ruby's well-spoken, college-educated father; and Willie "Lightning" Jefferson, a slow-moving Stepin Fetchit–type character.[8] Kingfish's catchphrase, "Holy mackerel!", entered the American lexicon.

There were three central characters: Correll voiced Andy Brown while Gosden voiced both Amos and the Kingfish. The majority of the scenes were dialogues between either Andy and Amos or Andy and Kingfish. Amos and Kingfish rarely appeared together. Since Correll and Gosden voiced virtually all of the parts, the female characters, such as Ruby Taylor, Kingfish's wife Sapphire, and Andy's various girlfriends, did not initially appear as voiced characters, but entered plots through discussions among the male characters. Prior to 1931, when Madame Queen (then voiced by Gosden) took the witness stand in her breach-of-promise lawsuit against Andy, a feminine voice was heard only once.[23] Beginning in 1935, actresses began voicing the female characters, and after the program converted to a weekly situation comedy in 1943, other actors were recruited for some of the supporting male roles.[3][8] However, Correll and Gosden continued to voice the three central characters on radio until the series ended in 1960. Two black actresses continued their radio roles on the television series:[24] Ernestine Wade, who played Sapphire, Kingfish's wife, and Amanda Randolph, who played her mother.

With the listening audience increasing in spring and summer 1928, the show's success prompted sponsor Pepsodent Company to bring it to the NBC Blue Network on August 19, 1929.[25] With the Blue Network not heard on stations in the Western United States, many listeners complained to NBC that they wanted to hear the show but could not. Under a special arrangement, Amos 'n' Andy debuted coast-to-coast November 28, 1929, on NBC's Pacific Orange Network and continued on the Blue. WMAQ was then an affiliate of CBS and its general manager tried, to no avail, to interest that network in picking up the show.[8] At the same time, the serial's central characters – Amos, Andy and Kingfish – relocated from Chicago to Harlem. The program was so popular by 1930 that NBC's orders were to only interrupt the broadcast for matters of national importance and SOS calls. Correll and Gosden were earning a combined salary of $100,000, which they split three ways to include announcer Bill Hay, who had been with them when they began in radio.[26][27]

The story arc of Andy's romance (and subsequent problems) with Harlem beautician Madame Queen entranced some 40 million listeners during 1930 and 1931, becoming a national phenomenon.[23][28] Many of the program's plotlines in this period leaned far more to straight drama than comedy, including the near-death of Amos's fiancée Ruby from pneumonia in the spring of 1931[29] and Amos's brutal interrogation by police following the murder of cheap hoodlum Jack Dixon that December. Following official protests by the National Association of Chiefs of Police, Correll and Gosden were forced to abandon that storyline, turning the entire sequence into a bad dream, from which Amos gratefully awoke on Christmas Eve.

The innovations introduced by Gosden and Correll made their creation a turning point for radio drama, as noted by broadcast historian Elizabeth McLeod:[5]

As a result of its extraordinary popularity, Amos 'n' Andy profoundly influenced the development of dramatic radio. Working alone in a small studio, Correll and Gosden created an intimate, understated acting style that differed sharply from the broad manner of stage actors – a technique requiring careful voice modulation, especially in the portrayal of multiple characters. The performers pioneered the technique for varying both the distance from, and the angle of their approach to, the microphone to create the illusion of a group of characters.[26] Listeners could easily imagine that they were in the taxicab office, listening to the conversation of close friends. The result was a uniquely absorbing experience for listeners, who, in radio's short history, had never heard anything quite like Amos 'n' Andy.

While minstrel-styled wordplay humor was common in the formative years of the program, it was used less often as the series developed, giving way to a more sophisticated approach to characterization. Correll and Gosden were fascinated by human nature, and their approach to both comedy and drama was drawn from their observations of the traits and motivations that drive the actions of all people. While their characters often overlapped popular African-American stereotypes, there was also a universality to their characters which transcended race; beneath the dialect and racial imagery, the series celebrated the virtues of friendship, persistence, hard work, and common sense, and as the years passed and the characterizations were refined, Amos 'n' Andy achieved an emotional depth rivaled by few other radio programs of the 1930s.

Above all, Gosden and Correll were gifted dramatists. Their plots flowed gradually from one to the other, with minor subplots building in importance until they overtook the narrative, before receding to give way to the next major sequence; in this manner, seeds for storylines were often planted months in advance. This complex method of story construction kept the program fresh and enabled Correll and Gosden to keep their audiences in constant suspense. The technique that they developed for radio from that of the narrative comic strip endures as the standard method of storytelling in serial drama.

Only a few dozen episodes of the original series have survived in recorded form. However, numerous scripts from the original episodes have been discovered and were used by McLeod when preparing her previously cited 2005 book.

Amos 'n' Andy was officially transferred by NBC from the Blue Network to the Red Network in 1935, although the vast majority of stations carrying the show remained the same. Several months later, Gosden and Correll moved production of the show from NBC's Merchandise Mart studios in Chicago to Hollywood.[30][31] After a long and successful run with Pepsodent, the program changed sponsors in 1938 to Campbell's Soup; because of Campbell's closer relationship with CBS, the series switched to that network on April 3, 1939.

In 1943, after 4,091 episodes, the radio program transformed from a 15-minute CBS weekday dramatic serial to an NBC half-hour weekly comedy. While the five-a-week show often had a quiet, easygoing feeling, the new version was a full-fledged sitcom in the Hollywood sense, with a regular studio audience (for the first time in the show's history) and an orchestra. More outside actors, including many black comedy professionals, such as Eddie Green and James Baskett, were recruited for the cast.[32] Many of the half-hour programs were written by Joe Connelly and Bob Mosher, later the writing team behind Leave It to Beaver and The Munsters. In the new version, the Amos character became peripheral to the duo of Andy and Kingfish, although Amos was still featured in the traditional Christmas show,[3][33] which also became a part of the later television series.[34] The later radio program and the TV version were advanced for the time, depicting blacks in a variety of roles, including those of successful business owners and managers, professionals and public officials, in addition to the comic characters at the show's core.[35] It anticipated and informed many later comedies featuring working-class characters (both black and white), including The Honeymooners, All in the Family and Sanford and Son.

By the fall of 1948, the show was airing on CBS again.[36] In that same year, Correll and Gosden sold all rights to Amos 'n' Andy to CBS for a reported $2.5 million.[37]

Theme song

[edit]

The theme song for both the radio and TV versions is "The Perfect Song" by Joseph Carl Breil, who had written the score from which the song is taken for the silent film The Birth of a Nation (1915).

Sponsors

[edit]Advertising pioneer Albert Lasker often took credit for having created the show as a promotional vehicle. After the associations with Pepsodent toothpaste (1929–37) and Campbell's Soup (1937–43), primary sponsors included Lever Brothers's Rinso detergent (1943–50); the Rexall drugstore chain (1950–54); and CBS's own Columbia brand of television sets (1954–55). President Calvin Coolidge was said to be among the show's most devoted listeners. Huey P. Long took his nickname, "Kingfish", from the show. At the peak of its popularity, many movie theaters stopped their featured films for the 15 minutes of the Amos 'n' Andy show, playing the program through the theater's sound system or from a radio on the stage before resuming their film.[8] When some theaters began advertising this practice, NBC charged the theaters with copyright infringement, claiming that charging admission for a free broadcast was illegal.[38]

Opposition and the Pittsburgh Courier protest

[edit]The first sustained protest against the program found its inspiration in the December 1930 issue of Abbott's Monthly, when Bishop W. J. Walls of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church wrote an article sharply denouncing Amos 'n' Andy for its lower-class characterizations and "crude, repetitious, and moronic" dialogue. The Pittsburgh Courier was the second largest African-American newspaper at the time, and publisher Robert L. Vann expanded Walls' criticism into a full-fledged protest during a six-month period in 1931.[39] As part of Vann's campaign, more than 700,000 African-Americans petitioned the Federal Radio Commission to complain about the racist stereotyping on the show.[40]

Historian James N. Gregory writes that the program "became the subject of heated conflict within African American communities" and that, while the Pittsburgh Courier campaigned against the program, "the Chicago Defender lauded the show's wholesome themes and good-natured humor," going "so far as to feature Gosden and Correll at its annual community parade and picnic in 1931."[41]

Films

[edit]In 1930, RKO Radio Pictures brought Gosden and Correll to Hollywood to appear in an Amos 'n' Andy feature film, Check and Double Check (a catchphrase from the radio show). The cast included a mix of white and black performers (the latter including Duke Ellington and his orchestra) with Gosden and Correll playing Amos 'n' Andy in blackface.[42] The film pleased neither critics nor Gosden and Correll, but briefly became RKO's biggest box-office hit before King Kong (1933).

Audiences were curious to see what their radio favorites looked like and were expecting to see African Americans instead of white men in blackface. RKO ruled out any plans for a sequel.[43] Gosden and Correll did lend their voices to a pair of Amos 'n' Andy cartoon shorts produced by the Van Beuren Studios in 1934, The Rasslin' Match and The Lion Tamer. These were also not successful.[44] Years later, Gosden was quoted as calling Check and Double Check "just about the worst movie ever." Gosden and Correll also posed for publicity pictures in blackface. They were also stars of The Big Broadcast of 1936 as Amos and Andy.[45]

Television

[edit]Hoping to bring the show to television as early as 1946, Gosden and Correll searched for cast members for four years before filming began. CBS hired the duo as producers of the new television show.[37][46][47] According to a 1950 newspaper story, Gosden and Correll had initial aspirations to voice the characters Amos, Andy and Kingfish for television while the actors hired for these roles performed and apparently were to lip-sync the story lines.[48] A year later, both spoke about how they realized they were visually unsuited to play the television roles, citing difficulties with making the Check and Double Check film. No further mention was made about Gosden and Correll continuing to voice the key male roles in the television series.[49] Correll and Gosden did record the lines of the main male characters to serve as a guideline for the television show dialogue at one point. In 1951, the men targeted 1953 for their retirement from broadcasting; there was speculation that their radio roles might be turned over to black actors at that time.[50]

Adapted to television, The Amos 'n Andy Show was produced from June 1951 to April 1953 with 52 filmed episodes, sponsored by the Blatz Brewing Company.[35] The television series used black actors in the main roles, although the actors were instructed to keep their voices and speech patterns close to those of Gosden and Correll,[51] and was produced at the Hal Roach Studios for CBS. The series' theme song was based on the radio show's "The Perfect Song" but became Gaetano Braga's "Angel's Serenade", performed by The Jeff Alexander Chorus. The program debuted on June 28, 1951.[52][53]

The main roles in the television series were played by the following black actors:[54]

- Amos Jones – Alvin Childress

- Andrew Hogg Brown (Andy) – Spencer Williams

- George "Kingfish" Stevens – Tim Moore

- Sapphire Stevens – Ernestine Wade

- Ramona Smith (Sapphire's Mama) – Amanda Randolph

- Algonquin J. Calhoun – Johnny Lee[55]

- Lightnin' – Nick Stewart (billed as "Nick O'Demus")

- Ruby Jones – Jane Adams

- Uncredited cast in various episodes[56]

- Ruby Dandridge in various roles

- Dudley Dickerson in various roles

- Roy Glenn as numerous authority figures[57]

- Jester Hairston in various roles, a number of times as Henry Van Porter

- Theresa Harris as Gloretta

- Jeni Le Gon in various roles

- Sam McDaniel in various roles

- Lillian Randolph as Madame Queen

(2 episodes); Caroline's mother (1 episode) - Bill Walker in various roles

This time, the NAACP mounted a formal protest almost as soon as the television version began, describing the show as "a gross libel of the Negro and distortion of the truth".[35] In 1951 it released a bulletin on "Why the Amos 'n' Andy TV Show Should Be Taken Off the Air." It stated that the show "tends to strengthen the conclusion among uninformed and prejudiced people that Negroes are inferior, lazy, dumb, and dishonest, ... Every character" is "either a clown or a crook"; "Negro doctors are shown as quacks and thieves"; "Negro lawyers are shown as slippery cowards"; "Negro women are shown as cackling, screaming shrews"; "All Negroes are shown as dodging work of any kind"; and "Millions of white Americans see this Amos 'n' Andy picture of Negroes and think the entire race is the same."[58]

That pressure was considered a primary factor in the show's cancellation, even though it finished at #13 in the 1951–1952 Nielsen ratings and at #25 in 1952–1953[59] Blatz was targeted as well, finally discontinuing its advertising support in June 1953.[60] It has been suggested that CBS erred in premiering the show at the same time as the 1951 NAACP national convention, perhaps increasing the objections to it.[61] The show was widely repeated in syndicated reruns until 1966 when, in an unprecedented action for network television at that time, CBS finally gave in to pressure from the NAACP and the growing civil rights movement and withdrew the program. It was pulled from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's television network, which had been broadcasting it for almost a decade. The series would not be seen on American television regularly for 46 more years.[62][63] The television show has been available in bootleg VHS and DVD sets, which generally include up to 71 of the 78 known TV episodes.

When the show was canceled, 65 episodes had been produced. The last 13 of these episodes were intended to be shown on CBS during the 1953–54 season but were released with the syndicated reruns instead. An additional 13 episodes were produced for 1954–55 to be added to the syndicated rerun package. These episodes were focused on Kingfish, with little participation from Amos or Andy, because these episodes were to be titled The Adventures of Kingfish (though they ultimately premiered under the Amos 'n' Andy title.)[64] The additional episodes first aired on January 4, 1955.[65] Plans were made for a vaudeville act based on the television program in August 1953, with Tim Moore, Alvin Childress and Spencer Williams playing the same roles. It is not known whether there were any performances.[66] Still eager for television success, Gosden, Correll and CBS made initial efforts to give the series another try. The plan was to begin televising Amos 'n' Andy in the fall of 1956, with both of its creators appearing on television in a split screen with the proposed black cast.[67]

A group of cast members began a "TV Stars of Amos 'n' Andy" cross-country tour in 1956, which was halted by CBS; the network considered it an infringement of their exclusive rights to the show and its characters.[51] Following the threatened legal action that brought the 1956 tour to an end, Moore, Childress, Williams and Lee were able to perform in character for at least one night in 1957 in Windsor, Ontario.[68]

Later commentary on television series

[edit]In the summer of 1968, the premiere episode of the CBS News documentary series Of Black America, narrated by Bill Cosby, showed brief film clips of Amos 'n' Andy in a segment on racial stereotypes in vintage motion pictures and television programing.

In 1983, a one-hour documentary film titled Amos 'n' Andy: Anatomy of a Controversy aired in television syndication (and in later years, on PBS and on the Internet). It told a brief history of the franchise from its radio days to the CBS series, and featured interviews with surviving cast members as well as popular black television stars such as Redd Foxx and Marla Gibbs, who reflected on the show's impact on their careers. Foxx and Gibbs emphasized the importance of the show featuring black actors in lead roles and expressed disagreement with the NAACP's objections that had contributed to the program's downfall. The film also contained highlights of a select episode of the classic TV series ("Kingfish Buys a Lot") that had not been seen since it was pulled from the air in 1966.[69]

In Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates Jr.'s 2012 American Heritage article Growing Up Colored, he wrote: "And everybody loved Amos 'n Andy – I don't care what people say today....Nobody was likely to confuse them with the colored people we knew..."[70]

Twenty-first century airing of series

[edit]In 2004, the now-defunct Trio network returned Amos 'n' Andy to television for one night in an effort to reintroduce the series to 21st century audiences. Its festival featured the Anatomy of a Controversy documentary followed by the 1930 Check and Double Check film.[71]

In 2012, Rejoice TV, an independent television and Internet network in Houston, started airing the show weeknights on a regular, nationwide basis for the first time since CBS pulled the series from distribution in 1966.[72] Six years later, Rejoice TV folded, and the series was again pulled from widespread distribution. There are no current official plans to rerelease the series to nationwide television.

Ratings

[edit]Radio

[edit]| Month | Rating (% listeners)[73] |

|---|---|

| Jan 1930 | no data |

| Jan 1931 | 53.4 (CAB) |

| Jan 1932 | 38.1 (CAB) |

| Jan 1933 | 29.4 (CAB) |

| Jan 1934 | 30.3 (CAB) |

| Jan 1935 | 22.6 (CAB) |

| Jan 1936 | 22.6 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1937 | 18.3 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1938 | 17.4 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1939 | 14.4 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1940 | 11.6 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1941 | 11.9 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1942 | 11.5 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1943 | 9.4 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1944 | 17.1 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1945 | 16.5 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1946 | 17.2 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1947 | 22.5 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1948 | 23.0 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1949 | 20.1 (Hooper) |

| Jan 1950 | 19.7 (Nielsen) |

| Jan 1951 | 16.9 (Nielsen) |

| Jan 1952 | 17.0 (Nielsen) |

| Jan 1953 | 14.2 (Nielsen) |

| Jan 1954 | 8.2 (Nielsen) |

| Jan 1955 | no data |

Legal status

[edit]Although the characters of Amos and Andy themselves are in the public domain, as well as the show's trademarks, title, format, basic premise and all materials created prior to 1948 (Silverman vs CBS, 870 F.2d 40),[74] the television series itself is protected by copyright. CBS bought out Gosden & Correll's ownership of the program and characters in 1948 and the courts decided in the Silverman ruling that all post-1948 Amos 'n' Andy material was protected. All Amos 'n' Andy material created prior to 1948, such as episodes of the old radio show, are in the public domain.[75] The television series has never been officially released in home-video format, but many unlicensed bootleg compilations have been sold. In 1998, CBS initiated copyright infringement suits against three companies selling the videos and issued a cease-and-desist order to a national mail-order outfit that had offered episodes on videocassettes and advertised them in late-night television ads during the late 1990s.[76][77] However, the unlicensed sets continue to be sold. No official, licensed DVD or Blu-ray compilations have been released.[78]

Later years

[edit]In 1955, the format of the radio show was changed from a weekly to a daily early evening half-hour to include playing recorded music between sketches (with occasional guests appearing), and the series was renamed The Amos 'n' Andy Music Hall. The final Amos 'n' Andy radio show was broadcast on November 25, 1960.[3] Although by the 1950s the popularity of the show was well below its peak of the 1930s, Gosden and Correll had managed to outlast most of the radio shows that came in their wake.

Cartoon

[edit]In 1961, Gosden and Correll attempted one last televised effort, albeit in a "disguised" version.[79] They were the voices in a prime-time animated cartoon, Calvin and the Colonel, featuring anthropomorphic animals whose voices and situations were almost exactly those of Andy and the Kingfish (and adapting several of the original Amos 'n' Andy radio scripts).[7] This effort at reviving the series in a way that was intended to be less racially offensive ended after one season on ABC, although it remained quite popular in syndicated reruns in Australia for several years. Connelly and Mosher returned to produce the series and also wrote several episodes.

Legacy

[edit]In 1988, the Amos 'n' Andy program was inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame.[80] A pair of parallel, one-block streets in west Dallas, Texas are named Amos Street and Andy Street in honor of the characters.

The short-lived 1996 HBO sitcom The High Life was intended in part as an homage to Amos 'n' Andy, but with white characters.[81]

Blues guitarist Christone "Kingfish" Ingram was given the nickname "Kingfish" after the sitcom by one of his guitar teachers, Bill "Howl -N- Mad" Perry.[82]

The show was referenced by The Simpsons in "Duffless", the sixteenth episode of the fourth season, which premiered on February 18, 1993. While Homer is on a tour at the Duff brewery, an old ad for the brand is played, showing that Duff was a "proud sponsor" of Amos 'n' Andy back in the 50s.

In the 1994 film Pulp Fiction, Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman) and Vincent Vega (John Travolta) visit a '50s-themed diner that offers on its menu an "Amos 'n' Andy" milkshake.[83]

Later work by television cast members

[edit]Comedian Tim Moore made numerous public appearances and was a guest on television on shows such as Jack Paar's Tonight Show and the Paul Coates Show.[84][85] In 1958, he headlined a standup comedy act at the Mocambo Night Club in Hollywood.[86]

Ernestine Wade (Sapphire) and Lillian Randolph (Madame Queen) appeared together on an episode of That's My Mama called "Clifton's Sugar Mama" on October 2, 1974.[87] They were friends of "Mama," played by Theresa Merritt, who wanted to see Clifton, played by Clifton Davis (later of the TV show Amen), at the beginning of the episode. Wade played Augusta and Randolph played Mrs. Birdie.

Jester Hairston (who played Henry Van Porter and Leroy Smith) was a regular on both That's My Mama as "Wildcat" and on Amen as "Rolly Forbes."[88] He was also quite prominent in a brief role as a butler in the racially charged film In the Heat of the Night (1967).

Amanda Randolph (Sapphire's mother, Ramona Smith) had a recurring role as Louise the housekeeper on CBS's The Danny Thomas Show and appeared in the show's 1967 reunion program, which aired shortly after her death.

Nick Stewart (Lightnin') had a memorable cameo in It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963) as a hapless driver run off the highway. Stewart and Johnny Lee (Calhoun) both provided voices in the Walt Disney film Song of the South in 1946. Johnny did the voice of Br'er Rabbit and Nick was heard as Br'er Bear.[89] The film also starred black actor James Baskett, who had voiced the Gabby Gibson character in the radio series.

References

[edit]- ^ "Amos 'n' Andy Illustrated". Midcoast. Archived from the original on December 16, 2004. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ "Del Sharbutt, 90; Radio Announcer and Emcee, Musician, Songwriter". The Los Angeles Times. May 1, 2002.

- ^ a b c d Sterling, Christopher H., ed. (2003). Encyclopedia of Radio 3-Volume Set. Routledge. p. 1696. ISBN 1579582494. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ Niemann, Greg (2006). Palm Springs Legends: creation of a desert oasis. San Diego, CA: Sunbelt Publications. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-932653-74-1. OCLC 61211290. (here for Table of Contents)

- ^ a b c McLeod, Elizabeth. The Original Amos 'n' Andy: Freeman Gosden, Charles Correll and the 1928–1943 Radio Serial. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005. ISBN 0-7864-2045-6

- ^ a b Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 31–36. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- ^ a b Cox, Jim, ed. (2002). Say Goodnight Gracie: The Last Years of Network Radio. McFarland and Company. p. 224. ISBN 0786411686. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j McLeod, Elizabeth. "Amos 'n' Andy In Person". McLeod, Elizabeth. Archived from the original on August 24, 2004. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Paul Ash". Red Hot Jazz. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ a b Coleman, Robin R. Means, ed. (1998). African American Viewers and the Black Situation Comedy: Situating Racial Humor (Studies in African American History and Culture). Routledge. p. 384. ISBN 0815331258. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Sam 'n' Henry". The Evening Independent. 6 June 1927. Retrieved 11 October 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "W-G-N radio program". Chicago Daily Tribune, January 29, 1928.

- ^ "W-G-N radio program". Chicago Daily Tribune, July 14, 1928.

- ^ Hilmes, Michelle, ed. (1997). Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922–1952. University of Minnesota Press. p. 384. ISBN 0816626219. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ "Tom Gootee's History of WMAQ – Chapter 12". Samuels, Rich.

- ^ "Amos 'n' Andy Illustrated". Midcoast. Archived from the original on February 17, 2005. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ "Palm Springs Home To Radio Veterans: Stars of 'Golden Era'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. AP. December 18, 1974. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ "Amos 'n' Andy Fresh Air Taxi". Strong National Museum of Play. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ^ "Marx Amos 'N' Andy Fresh Air Taxi". Live Auctioneers. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ^ Correll, Charles J.; Gosden, Freeman F., eds. (1929). All About Amos 'n' Andy and Their Creators. Rand McNally. p. 128. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ Hay, Bill. "All About Amos 'n' Andy – Forward". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ "Knights of the Mystic Sea – Kingfish from Amos and Andy".

- ^ a b "How Andy's Famous Lawsuit Was Broadcast; Amos 'n' Andy Creators Took All Parts in Trial". Spokane Daily Chronicle. 30 March 1931. Retrieved 11 October 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Amos 'n' Andy - OTR".

- ^ "Amos 'n' Andy To Start New Radio Series". The Pittsburgh Press. 28 July 1929. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ a b Brill, A. A., ed. (1930). Amos 'n' Andy Explained. Popular Science. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ The March of Radio (PDF). Radio Broadcast. 1929. p. 273. Retrieved March 6, 2014.[permanent dead link](PDF)

- ^ Jones, Gerard, ed. (1993). Honey, I'm Home!: Sitcoms: Selling The American Dream. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 291. ISBN 0312088108. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Nachman, Gerald, ed. (2000). Raised on Radio. University of California Press. p. 544. ISBN 0520223039. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Samuels, Rich. "WMAQ-Amos 'n' Andy". Samuels, Rich. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Samuels, Rich. "Audio files from the Chicago years of Amos 'n' Andy". Samuels, Rich. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Amos 'n' Andy Coming Back". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. 19 August 1943. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Rayburn, John, ed. (2008). Cat Whiskers and Talking Furniture: Memoir of Radio and Television Broadcasting. McFarland. p. 256. ISBN 978-0786436972. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- ^ MacDonald, J. Fred. "Blacks and White TV: African Americans in Television Since 1948". jfredmacdonald.com. Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Von Schilling, Jim, ed. (2002). The Magic Window: American Television, 1939–1953. Routledge. p. 260. ISBN 0789015064. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ "Amos 'n' Andy Radio Logs". Jerry Haendiges Vintage Radio Logs. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Amos 'n' Andy Look For Exit As They Plan New TV Show". Reading Eagle. 17 June 1951. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ "Amos 'n' Andy Illustrated". Midcoast. Archived from the original on December 17, 2004. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ Barlow, William, ed. (1998). Voice Over: The Making of Black Radio. Temple University Press. p. 334. ISBN 1566396670. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

all about amos 'n' andy.

- ^ Gonzalez, Juan; Torres, Joseph (2011). News For All The People. Verso. p. 9.

- ^ Gregory, James N. (2005). The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8078-5651-2.

- ^ Steinhauser, S. H. (19 October 1930). "Fooling Their Friends Big Job for Amos 'n' Andy in the Movies". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Lawrence, A. H., ed. (2003). Duke Ellington and His World. Routledge. p. 492. ISBN 0415969255. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Lehman, Christopher P., ed. (2009). The Colored Cartoon. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-1558497795. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Radio's Famous 'Amos' Dead at 83". Gadsden Times. 11 December 1982. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Hawes, William, ed. (2001). Filmed Television Drama 1952–1958. McFarland. p. 304. ISBN 0786411325. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Radio's Veteran Comics Smash Hit on Television". Eugene Register-Guard. 14 April 1954. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Steinhauser, Si (13 December 1950). "Amos 'n' Andy Chose Negro Stars for TV Film: Originals to Be Heard, not Seen". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Quigg, Jack (10 June 1951). "Declare: 'TV not for us'". Youngstown Vindicator. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Handsacker, Gene (29 July 1951). "Hollywood Sights and Sounds". Prescott Evening Courier. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ a b Clayton, Edward T. (1961). The Tragedy of Amos 'n' Andy. Ebony. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ "Amos And Andy Name Subs For Television Roles". St. Petersburg Times. 18 June 1951. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "'Amos 'n' Andy' Characters Use Satire, Not Comedy". Baltimore Afro-American. 18 August 1951. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Morreale, Joanne, ed. (2002). Critiquing the Sitcom: A Reader (The Television Series). Syracuse University Press. p. 320. ISBN 0815629834. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ 'Lawyer Calhoun' of Radio, TV. Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. 1965. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ The Amos 'n' Andy Show – Full Cast List on IMDb

- ^ Roy Glenn Film and TV Credits on IMDb

- ^ "'The Gilded Age' Is Depicting Black Success. More TV Should". New York Times. 18 February 2021.

- ^ "ClassicTVguide.com: TV Ratings". classictvguide.com.

- ^ "Beer Sponsors To Drop Amos 'n' Andy Show". The Afro American. 14 March 1953. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ^ Dudek, Duane (21 August 1991). "Book recounts story of popular, problematic 'Amos 'n' Andy'". The Milwaukee Sentinel.

- ^ "Amos & Andy goes to television". African-American Registry. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ "Why the Amos 'n' Andy TV Show Should Be Taken Off the Air". NAACP Bulletin. 15 August 1951. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ Kantor, Michael; Maslon, Lawrence, eds. (2008). Make 'Em Laugh: The Funny Business of America. Twelve. p. 384. ISBN 978-0446505314. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ New 'Kingfish' Series To Make TV Debut Jan. 4. Jet. 1955. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "'Amos 'n' Andy' Set for Vaude". Baltimore Afro-American. 4 August 1953. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ 'Amos 'n' Andy' Creators Plan New TV Show. Jet. 1955. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ Gardiner, John (25 June 1957). "The Theatre and its People". The Windsor Daily Star. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ Steelman, Ben (17 November 1985). "From Star Wars to Amos 'n' Andy". Star-News. Retrieved 11 October 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Growing up Colored | American Heritage". American Heritage.

- ^ MacDonald, J. Fred. "Blacks and White TV, African Americans in Television Since 1948". jfredmacdonald.com. Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Tom Abrahams. 'Amos and Andy' on the air in Houston. ABC 13 Eyewitness News, Houston. 20 Nov 2012.

- ^ Harrison B. Summers (1958). A Thirty-Year History of Programs Carried on National Radio Networks in the United States.

- ^ N. Y. Writer Battling CBS For 'Amos 'n' Andy' Rights. Jet. 23 September 1985. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Gerard, Jeremy (9 February 1989). "TV Notes". New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ CBS Files Suit Over 'Amos 'n' Andy' Videos. Jet. 13 November 1989. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ Elliott, Stuart (19 August 1997). "Disputes develop over the comeback of 'Amos 'n Andy.'". New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ ""Amos 'n' Andy" Resource Page". Archived from the original on 2017-07-02. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ^ "The Controversy Over "Calvin and The Colonel" |". cartoonresearch.com.

- ^ "Amos 'n' Andy". Radio Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Evans, Bradford (May 28, 2014). "Inside Adam Resnick's Proudest and Most Embarrassing Projects". Vulture.

- ^ "How a 23-Year-Old Phenom Named Kingfish Became the Future of the Blues". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2022-07-26.

- ^ Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (1996). Tarantino A to Zed: The Films of Quentin Tarantino. B. T. Batsford Ltd. p. 17. ISBN 978-0713479904.

- ^ "The Daily Mirror". Los Angeles Times. 29 January 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ Words Of The Week. Jet. 23 January 1958. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Tim Moore". BlackPast.org. 23 February 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ "Actress from the Delta, Ernestine Wade". African-American Registry. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- ^ Fearn-Burns, Kathleen, ed. (2005). Historical Dictionary of African-American Television (Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts). The Scarecrow Press. p. 584. ISBN 0810853353. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Johnny Lee". Black-face.com. Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

External links

[edit]- The Amos 'n Andy Show at IMDb

- Amos 'n' Andy: Past as Prologue?

- Meet Amos 'n' Andy

- Rechecking Check and Double Check

- Rich Samuels' Broadcasting in Chicago: 1921–1989

- Amos 'n' Andy History of the 1950s TV Show

- Eddie Green The Rise of an Early 1900s Black American Entertainment Pioneer

Audio

[edit]- Amos 'n' Andy discuss the Presidential election

- Amos & Andy Show on Way Back When Archived 2013-10-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Archive.org Old Time Radio – Amos 'n' Andy

- OTR Fans: Amos and Andy (23 episodes) Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Amos 'n' Andy – OTR – Old Time Radio (108 episodes)

- OTR Network Library: Amos 'n' Andy (219 episodes)

- Tom Heathwood interviews broadcast historian Elizabeth McLeod Archived 2013-07-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Zoot Radio, Free Amos 'n' Andy radio show downloads

- Amos & Andy Show on Old Time Radio Outlaws

Video

[edit]- Amos 'n' Andy

- American comedy radio programs

- 1928 radio programme debuts

- 1960 radio programme endings

- Radio duos

- Male characters in radio

- NBC Blue Network radio programs

- Radio programs adapted into television shows

- 1920s American radio programs

- 1930s American radio programs

- 1930s in comedy

- 1940s American radio programs

- 1950s American radio programs

- 1951 American television series debuts

- 1953 American television series endings

- 1950s American sitcoms

- American black sitcoms

- Black-and-white American television shows

- American English-language television shows

- Fictional African-American people

- Radio characters introduced in 1928

- Television characters introduced in 1951

- First-run syndicated television programs in the United States

- Television series based on radio series

- Television series by CBS Studios

- Television shows set in New York City

- Victor Records artists

- Columbia Records artists

- Comedy radio characters

- Comedy television characters

- Male characters in television

- Ethnic humour

- Race-related controversies in radio

- Race-related controversies in television

- Television controversies in the United States

- CBS sitcoms