The American Crisis

The first page of the original printing of the first volume | |

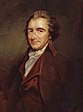

| Author | Thomas Paine |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

Publication date | 1776–1783 |

The American Crisis, or simply The Crisis,[1] is a pamphlet series by eighteenth-century Enlightenment philosopher and author Thomas Paine, originally published from 1776 to 1783 during the American Revolution.[2] Thirteen numbered pamphlets were published between 1776 and 1777, with three additional pamphlets released between 1777 and 1783.[3] The first of the pamphlets was published in The Pennsylvania Journal on December 19, 1776.[4] Paine signed the pamphlets with the pseudonym, "Common Sense".

The pamphlets were contemporaneous with early parts of the American Revolution, when colonists needed inspiring works. The American Crisis series was used to "recharge the revolutionary cause."[5] Paine, like many other politicians and scholars, knew that the colonists were not going to support the American Revolutionary War without proper reason to do so. Written in a language that the common person could understand, they represented Paine's liberal philosophy. Paine also used references to God, saying that a war against Great Britain would be a war with the support of God. Paine's writings bolstered the morale of the American colonists, appealed to the British people's consideration of the war, clarified the issues at stake in the war, and denounced the advocates of a negotiated peace. The first volume famously begins: "These are the times that try men's souls."

Themes

[edit]Winter 1776 was a time of need in the colonies, considering Philadelphia and the entire rebel American cause were on the verge of death and the revolution was still viewed as an unsteady prospect. Paine wanted to enable the distraught patriots to stand, to persevere, and to fight for an American victory. Paine published the first Crisis paper on December 19.[6]

Its opening sentence was adopted as the watchword of the movement to Trenton. The opening lines are as follows:[7]

These are the times that try men's souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.

Paine brought together the thirteen diverse colonies and encouraged them to stay motivated through the harsh conditions of the winter of 1776. Washington's troops were ready to quit until ordered by Washington to be read aloud Paine's Crisis paper and heard the first sentence, “These are the times that try men’s souls.”[5] The pamphlet, read aloud to the Continental Army on December 23, 1776, three days before the Battle of Trenton[citation needed], attempted to bolster morale and resistance among patriots, as well as shame neutrals and loyalists to support the cause:

Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.

Along with the patriotic nature of The American Crisis, the series of papers displayed Paine's strong deist beliefs,[8] inciting the laity with suggestions that the British are trying to assume powers that only God should have. Paine saw the British political and military maneuvers in the colonies as "impious; for so unlimited a power can belong only to God." Paine stated that he believed that God supported the cause of the American colonists, "that God Almighty will not give up a people to military destruction, or leave them unsupportedly to perish, who have so earnestly and so repeatedly sought to avoid the calamities of war, by every decent method which wisdom could invent".

Paine goes to great lengths to state that American colonists do not lack force but "a proper application of that force," implying throughout that an extended war could lead only to defeat unless a stable army was composed not of militia but of trained professionals. Paine maintains a positive view overall, hoping that the American crisis could be resolved quickly "for though the flame of liberty may sometimes cease to shine, the coal can never expire. and goes on to state that Great Britain has no right to invade the colonies, saying that it is a power belonging "only to God. Paine also asserts that "if being bound in that manner is not slavery, then there is not such a thing as slavery on earth." Paine obviously believes that Great Britain is essentially trying to enslave the American colonists. He then opines a little about how the panicking of the sudden Revolutionary War has both hindered and helped the colonists.

Paine then speaks of his experience in the Battle of Fort Lee and the colonists' subsequent retreat. Afterward, Paine remarks on an experience with a Loyalist. He says the man told his child, "'Well! give me peace in my day,'" meaning he did not want the war to happen in his lifetime. Paine says that this is very "unfatherly" and the man should want the war to happen in his time so it does not happen in his child's time. Paine then gives some advice on how to do better in the war. Paragraph 1 is about the present. The present is a time to secure the celestial article of freedom and merit the honor of commercial appreciation. Paine encourages the colonists to value victory and its consequent freedom because “the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph”—“what we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly,” he notes, and “ it is dearness only that gives every thing its value.”[6] Crisis No. 1 concludes with a few paragraphs of encouragement, a vivid description of what will happen if colonists act like cowards and give up, and the closing statement, "Look on this picture and weep over it! and if there yet remains one thoughtless wretch who believes it not, let him suffer it unlamented."

Dates and places of publication

[edit]The Crisis series appeared in a range of publication formats, sometimes (as in the first four) as stand-alone pamphlets and sometimes in one or more newspapers.[9] In several cases, too, Paine addressed his writing to a particular audience, while in other cases he left his addressee unstated, writing implicitly to the American public (who were, of course, his actually intended audience at all times).

| Number | Date of First Appearance | Printer / Publication Venue | Addressed to: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number I | December 19, 1776 | Styner and Cist (Philadelphia)[10] | -- |

| Number II | January 17, 1777 | Styner and Cist (Philadelphia)[11] | “TO LORD HOWE” |

| Number III | April 25, 1777 | Styner and Cist (Philadelphia)[12] | -- |

| Number IV | September 13, 1777 | Styner and Cist (Philadelphia)[13] | -- |

| Number V | March 23, 1778 | John Dunlap (Lancaster, PA)[14] | “TO GENERAL SIR WILLIAM HOWE” (part 1) / “TO THE INHABITANTS OF AMERICA” (part 2) |

| “Number VI” | October 22, 1778 | Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphia)[9] | “TO THE EARL OF CARLISLE, GENERAL CLINTON, AND WILLIAM EDEN, ESQ” |

| “Number VII” | November 12, 1778 | Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphia)[9] | “TO THE PEOPLE OF ENGLAND” |

| “Number VIII” | February 26, 1780 | Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphia)[9] | “TO THE PEOPLE OF ENGLAND” |

| “No. IX” | June 10, 1780 | Pennsylvania Packet (Philadelphia)[9] | -- |

| The Crisis Extraordinary | October 7, 1780 | William Harris (Philadelphia)[15] | -- |

| “Number XI” | May 11, 1782 | Pennsylvania Packet / Pennsylvania Journal (both Philadelphia)[9] | -- |

| “The Last Crisis, Number XIII” | April 19, 1783 | Pennsylvania Packet / Pennsylvania Journal (both Philadelphia)[9] | -- |

Contents

[edit]The first Crisis pamphlet opens with the famous sentence, "These are the times that try men's souls,"[16] and goes on to state that Great Britain has no right to invade the colonies, saying that it is a power belonging "only to God."[16] Paine also asserts that "if being bound in that manner is not slavery, then there is not such a thing as slavery on earth."[16] Paine obviously believes that Great Britain is essentially trying to enslave the American colonists. He then opines a little about how the panicking of the sudden Revolutionary War has both hindered and helped the colonists. Paine then speaks of his experience in the Battle of Fort Lee and the colonists' subsequent retreat.

Afterward, Paine remarks on an experience with a Loyalist. He says the man told his child, "'Well! give me peace in my day,'"[16] meaning he did not want the war to happen in his lifetime. Paine says that this is very "unfatherly" and the man should want the war to happen in his time so it does not happen in his child's time. Paine then gives some advice on how to do better in the war.[16] Paragraph 1 is about the present. The present is a time to secure the celestial article of freedom and merit the honor of commercial appreciation. Paine encourages the colonists to value victory and its consequent freedom because “the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph”—“what we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly,” he notes, and “ it is dearness only that gives every thing its value.”[6] Crisis No. 1 concludes with a few paragraphs of encouragement, a vivid description of what will happen if colonists act like cowards and give up, and the closing statement, "Look on this picture and weep over it! and if there yet remains one thoughtless wretch who believes it not, let him suffer it unlamented."[16]

Crisis No. 2, addressed "To Lord Howe," begins, "Universal empire is the prerogative of a writer." Paine makes plain his judgment that Howe was but a sycophant of George III: "Perhaps you thought America too was taking a nap, and therefore chose, like Satan to Eve, to whisper the delusion softly, lest you should awaken her. This continent, Sir, is too extensive to sleep all at once, and too watchful, even in its slumbers, not to startle at the unhallowed foot of an invader." Paine makes it clear that he believes that George is not up to his former standards when it came to his duties with the American colonies. Paine also sheds light onto what he felt the future would hold for the emerging country, "The United States of America, will sound as pompously in the world, or in history [as] the Kingdom of Great Britain; the character of General Washington will fill a page with as much luster as that of Lord Howe; and Congress have as much right to command the king and parliament of London to desist from legislation, as they or you have to command the Congress."[17]

Paine then goes on to try to bargain with George: "Why, God bless me! What have you to do with our independence? we asked no leave of yours to set it up, we asked no money of yours to support it; we can do better without your fleets and armies than with them; you may soon have enough to do to protect yourselves, without being burthened with us. We are very willing to be at peace with you, to buy of you and sell to you, and, like young beginners in the world, to work for our own living; therefore, why do you put yourselves out of cash, when we know you cannot spare it, and we do not desire you to run you into debt?"[17] In the conclusion Paine explains that he considers "independence as America's natural right and interest, and never could see any real disservice it would be to Britain."

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Davis, Kenneth C. (2003). Don't Know Much About History: Everything You Need to Know About American History but Never Learned (1st ed.). New York: HarperCollins. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-06-008381-6.

- ^ "The Crisis by Thomas Paine". www.ushistory.org. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ Foner, Phillip S, The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, Vol. 2 (New York: Citadel Press, 1945) p. 48

- ^ "Thomas Paine publishes American Crisis – Dec 19, 1776 – Histort..com". History.com. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Dennehy, Robert F.; Morgan, Sandra; Assenza, Pauline (2006). "Thomas Paine: Creating the New Story for a New Nation". Tamara Journal of Critical Organisation Inquiry. 5 (3 & 4). Warsaw: 183–192. ProQuest 204425669.

- ^ a b c Gallagher, Edward J. (April–June 2010). "Thomas Paine's CRISIS 1 and the Comfort of Time". The Explicator. 68 (2). Washington: 87–89. ProQuest 578500565.

- ^ William B. Cairns (1909), Selections from Early American Writers, 1607–1800, The Macmillan company, pp. 347–352, retrieved November 25, 2007

- ^ "Age of Reason, Part II, Section 21". www.ushistory.org. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Paine, Thomas (March 1, 1995). Thomas Paine: Collected Writings (LOA #76): Common Sense / The American Crisis / Rights of Man / The Age of Reason / pamphlets, articles, and letters. Library of America. ISBN 978-1-59853-179-4.

- ^ Conner, Jett (January 4, 2016). "A Brief Publication History of the "Times That Try Men's Souls"". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- ^ Paine, Thomas (1777). The American crisis. Number II. Styner and Cist. Retrieved December 17, 2021 – via Evans Early American Imprint Collection.

- ^ Paine, Thomas (1777). The American crisis. Number III. Styner and Cist. Retrieved December 17, 2021 – via Evans Early American Imprint Collection.

- ^ Paine, Thomas (1777). The American crisis. Number IV. Styner and Cist. Retrieved December 17, 2021 – via Evans Early American Imprint Collection.

- ^ Paine, Thomas (1778). The American crisis. Number V. Styner and Cist. Retrieved December 17, 2021 – via Evans Early American Imprint Collection.

- ^ Paine, Thomas (1780). The crisis extraordinary. William Harris. Retrieved December 17, 2021 – via Evans Early American Imprint Collection.

- ^ a b c d e f Baym, Nina; Levine, Robert S. (2012). The Norton Anthology of American Literature. Vol. A. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 647–653. ISBN 978-0-393-93476-2.

- ^ a b Paine, Thomas (1819). The American Crisis. R. Carlile.