Valinor

| Valinor | |

|---|---|

| Tolkien's legendarium location | |

| First appearance | The Lord of the Rings |

| Created by | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| In-universe information | |

| Other name(s) | The Undying Lands, The Blessed Realm, The Uttermost West, Aman |

| Type | Continent |

| Ruler | Manwë |

| Characters | Valar, Elves |

| Location | On the west of The Great Sea, far to the West of Middle-earth |

Valinor (Quenya: Land of the Valar) or the Blessed Realm is a fictional location in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, the home of the immortal Valar on the continent of Aman, far to the west of Middle-earth; he used the name Aman mainly to mean Valinor. It includes Eldamar, the land of the Elves, who as immortals are permitted to live in Valinor.

Aman is known as "the Undying Lands", but the land itself does not cause mortals to live forever.[T 1] However, only immortal beings are generally allowed to reside there. Exceptions are made for the surviving bearers of the One Ring: Bilbo and Frodo Baggins and Sam Gamgee, who dwell there for a time, and the dwarf Gimli.[T 2][T 3]

Tolkien's myth of the attempt of Númenor to capture Aman has been likened to the biblical Tower of Babel and the ancient Greek Atlantis, and the resulting destruction in both cases. They note, too, that a mortal's stay in Valinor is only temporary, not conferring immortality, just as, in medieval Christian theology, the Earthly Paradise is only a preparation for the Celestial Paradise that is above.

Others have compared the account of the beautiful Elvish part of the Undying Lands to the Middle English poem Pearl, and stated that the closest literary equivalents of Tolkien's descriptions of these lands are the imrama Celtic tales such as those about Saint Brendan from the early Middle Ages. The Christian theme of good and light (from Valinor) opposing evil and dark (from Mordor) has also been discussed.

Geography

[edit]

Physical

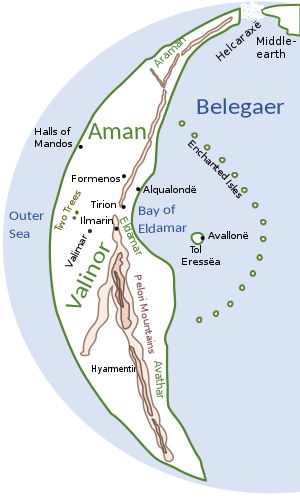

[edit]Valinor lies in Aman ("Unmarred"[1]), a continent on the west of Belegaer, the ocean to the west of Middle-earth.[2] Ekkaia, the encircling sea, surrounds both Aman and Middle-earth. Tolkien wrote that the name "Aman" was "chiefly used as the name of the land in which the Valar dwelt".[T 4] The Pelóri mountains run along the east coast; their highest peak is Taniquetil.[T 5] Tolkien created no detailed maps of Aman; those drawn by Karen Wynn Fonstad, based on Tolkien's rough sketch of Arda's landmasses and seas, show Valinor about 700 miles (1,100 km) wide, west to east (from the Great Sea to the Outer Sea), and about 3,000 miles (4,800 km) long north to south. The continent of Aman extends from the Arctic latitudes of the Helcaraxë to the subpolar southern region of Arda – about 7,000 miles (11,000 km).[3]

Eldamar is "Elvenhome", the "coastal region of Aman, settled by the Elves", wrote Tolkien.[T 6][4] Eldamar was the true Eldarin name of Aman.[T 7] In The Hobbit it is named "Faerie". The land is well-wooded, as Finrod "walk[ed] with his father under the trees in Eldamar" and the Teleri Elves have timber to build their ships. The city of the Teleri, on the north shore of the Bay is Alqualondë, the Haven of the Swans, whose halls and mansions are made of pearl. The harbour is entered through a natural arch of rock, and the beaches are strewn with gems given by the Noldor Elves.[T 8] In the bay is the island of Tol Eressëa.[T 5]

Calacirya (Quenya: "Light Cleft", for the light of the Two Trees that streams through the pass into the world beyond) is the pass in the Pelóri mountains where the Elven city Tirion is set. It is close to the Girdle of Arda (the Equator).[3] After the hiding of Valinor, this is the only gap through the mountains of Aman.[T 5]

In the extreme north-east, beyond the Pelóri, is the Helcaraxë, a vast ice sheet that joins the two continents of Aman and Middle-earth before the War of Wrath.[T 9] To prevent anyone from reaching the main part of Valinor's east coast by sea, the Valar create the Shadowy Seas, and within these seas they set a long chain of islands called the Enchanted Isles.[T 10][5]

Political

[edit]Valinor is the home of the Valar (singular Vala), spirits that often take humanoid form, sometimes called "gods" by the Men of Middle-earth.[T 11] Other residents of Valinor include the related but less powerful spirits, the Maiar, and most of the Elves.[T 12]

Each Vala has his or her own region of the land. The Mansions of Manwë and Varda, two of the most powerful spirits, stands upon the top of Taniquetil.[T 11] Yavanna, the Vala of Earth, Growth, and Harvest, resides in the Pastures of Yavanna in the south of the land, west of the Pelóri. Nearby are the mansions of Yavanna's spouse, Aulë the Smith. Oromë, the Vala of the Hunt, lives in the Woods of Oromë to the north-east of the pastures. Nienna lives in the far west of the island. Just south of Nienna's home, and to the north of the pastures, are the Halls of Mandos; he lives with his spouse Vairë the weaver. To the east of the Halls of Mandos is the Isle of Estë, in the lake of Lórellin[T 11] within the Gardens of Lórien.[3]

In east-central Valinor at the Girdle of Arda is Valmar, the capital of Valinor (also called Valimar, the City of Bells), the residence of the Valar and the Maiar in Valinor. The first house of the Elves, the Vanyar, settles there as well. The mound of Ezellohar, on which stand the Two Trees, and Máhanaxar, the Ring of Doom, are outside Valmar.[T 12] Farther east is the Calacirya, the only easy pass through the Pelóri, a huge mountain range fencing Valinor on three sides, created to keep Morgoth's forces out. The city of the Noldor (and for a time the Vanyar Elves also) is Tirion, built on the hill of Túna, inside the Calacirya mountain pass; it is just north of Taniquetil, facing both the Two Trees and the starlit seas.[T 5][3]

In the northern inner foothills of the Pelóri, far to the north of Valmar, is Fëanor's city of Formenos, built after his banishment from Tirion.[T 13]

History

[edit]Years of the Trees

[edit]

Valinor is established on the western continent Aman when Melkor (a Vala later named Morgoth, "the black foe", by the Elves) destroys the Valar's original home on the island Almaren in primeval Middle-earth, ending the Years of the Lamps.[T 12] To defend their new home from attack, they raise the Pelóri Mountains.[T 12] They also establish Valimar, the radiant Two Trees, and their dwelling-places.[T 12][T 14] Valinor is said to surpass Almaren in beauty.[T 12] Later, the Valar hear of the awakening of the Elves in Middle-earth, where Melkor is unopposed. They propose to bring the Elves to the safety of Valinor, but to do that, they need to get Melkor out of the way. A war is fought, and Melkor's stronghold Utumno is destroyed. Then, many Elves come to Valinor, and establish their cities Tirion and Alqualondë, beginning Valinor's age of glory. Melkor comes back to Valinor as a prisoner, and after three Ages is brought before the Valar; he sues for pardon, vowing to assist the Valar and make amends for the hurts he has done. Manwë grants him pardon, but confines him within Valmar to remain under watch.[T 9] After his release, Melkor starts planting seeds of dissent in the minds of the Elves, including between Fëanor and his brothers Fingolfin and Finarfin. Fëanor uses some of the light of the Two Trees to forge the three Silmarils, beautiful and irreplaceable jewels.[T 13]

The Darkening of Valinor

[edit]Belatedly, the Valar learn what Melkor has done. Knowing that he is discovered, Melkor goes to the home of the Noldor's High King Finwë, kills him and steals the Silmarils. He then destroys the Two Trees with the help of Ungoliant, plunging Valinor into darkness, the Long Night, relieved only by stars. Melkor and Ungoliant flee to Middle-earth.[T 15]

The Hiding of Valinor

[edit]

The Valar manage to save one last luminous flower from one of the Two Trees, Telperion, and one last luminous fruit from the other, Laurelin. These become the Moon and the Sun. The Valar carry out further titanic labours to improve the defences of Valinor. They raise the Pelóri mountains to even greater and sheerer heights. Off the coast, eastwards of Tol Eressëa, they create the Shadowy Seas and their Enchanted Isles; both the Seas and the Isles present numerous perils to anyone attempting to get to Valinor by sea.[T 10]

Later history

[edit]For centuries, Valinor take no part in the struggles between the Noldor and Morgoth in Middle-earth. But near the end of the First Age, when the Noldor are in total defeat, the mariner Eärendil convinces the Valar to make a last attack on Morgoth. A mighty host of Maiar, Vanyar and the remaining Noldor in Valinor destroy Morgoth's gigantic army and his stronghold Angband, and cast Morgoth into the void.[T 16]

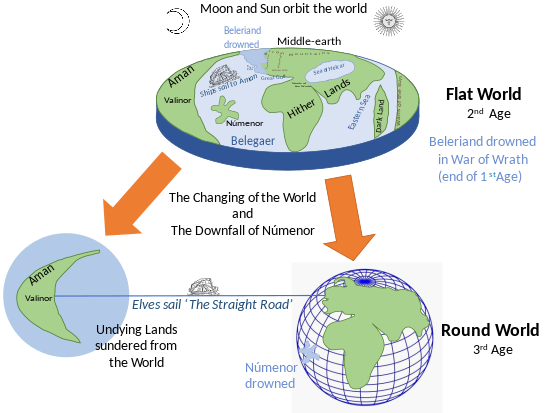

During the Second Age, the Valar create the island of Númenor as a reward to the Edain, Men who had fought alongside the Noldor. Centuries later the kingdom of Númenor grows so powerful and so arrogant that Ar-Pharazôn, the twenty-fifth and last king, dares to attempt an invasion of Valinor. When the creator Eru Ilúvatar responds to the call of the Valar, Númenor sinks into the sea, and Aman is removed beyond the reach of the Men of Arda. Arda itself becomes spherical, and is left for Men to govern. The Elves can go to Valinor only by the Straight Road and in ships capable of passing out of the spheres of the earth.[T 17][6]

Analysis

[edit]Paradise

[edit]

Keith Kelly and Michael Livingston, writing in Mythlore, note that Frodo's final destination, mentioned at the end of The Lord of the Rings, is Aman, the Undying Lands. In Tolkien's mythology, they write, the islands of Aman are initially just the dwelling-places of the Valar (in the Ages of the Trees, while the rest of the world lies in darkness). The Valar help The One, Eru Ilúvatar, to create the world. Gradually some of the immortal and ageless Elves are allowed to live there as well, sailing across the ocean to the West. After the fall of Númenor and the reshaping of the world, Aman becomes the place "between (sic) Over-heaven and Middle-earth".[8] It is accessible only in special circumstances like Frodo's, allowed to come to Aman through the offices of the Valar and of Gandalf, one of the Valar's emissaries, the Istari or Wizards. However, Aman is not, they write, exactly paradise. Firstly, being there does not confer immortality, contrary to what the Númenóreans supposed. Secondly, those mortals like Frodo who are allowed to go there will eventually choose to die. They note that in another of Tolkien's writings, "Leaf by Niggle", understood to be a journey through Purgatory (the Catholic precursor stage to paradise), Tolkien avoids describing paradise at all. They suggest that to the Catholic Tolkien, it is impossible to describe Heaven, and it might be sacrilege to make the attempt.[8] The Tolkien scholar Michael D. C. Drout comments that Tolkien's accounts of Eldamar "give us a good idea of his conceptions of absolute beauty".[7] He notes that these resemble the paradise described in the Middle English poem Pearl.[7]

| Tolkien | Catholicism | Pearl, Dante's Paradiso |

|---|---|---|

| "that which is beyond Elvenhome and will ever be"[T 18] | Heaven | Celestial Paradise, "beyond" |

| Undying lands of Aman, Elvenhome in Valinor | Purgatory | Earthly Paradise, Garden of Eden |

| Middle-earth | Earth | Earth |

The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey adds that in 1927 Tolkien wrote a poem, The Nameless Land, in the complex stanza-form of Pearl. It spoke of a land further away than paradise, and more beautiful than the Irish Tír na nÓg, the deathless otherworld.[6] Kelly and Livingston similarly draw on Pearl, noting that it states that "fair as was the hither shore, far lovelier was the further land"[8] where the Dreamer could not pass. So, they write, each stage looks like paradise, until the traveller realises that beyond it lies something even more paradisiacal, glimpsed and beyond description. The Earthly Paradise can be described; Aman, the Undying Lands, can thus be compared to the Garden of Eden, the paradise that the Bible says once existed upon Earth before the Fall of Man. The Celestial Paradise of Tolkien's "Leaf by Niggle" lies "beyond (or above)", as it does, they note, in Dante's Paradiso.[8] Matthew Dickerson notes that Valinor resembles the Garden of Eden in having two trees.[9]

Good against evil

[edit]The scholar of English literature Marjorie Burns writes that one of the female Vala, Varda (Elbereth to the Elves) is sung to by the Elf-queen of Middle-earth Galadriel. Burns notes that Varda "sits far off in Valinor on Oiolossë",[11] looking from her mountain-peak tower in Aman towards Middle-earth and the Dark Tower of Sauron in Mordor: she notes Timothy O'Neill's view that the white benevolent feminine symbol opposes the evil masculine symbol. Further, Burns suggests, Galadriel is an Elf from Valinor "in the Blessed Realm",[11] bringing Varda's influence with her to Middle-earth. This is seen in the phial of light that she gives to Frodo, and that Sam uses to defeat the evil giant spider Shelob: Sam invokes Elbereth when he uses the phial. Burns comments that Sam's request to the "Lady" sounds distinctly Catholic, and that the "female principle, embodied in Varda of Valinor and Galadriel of Middle-earth, most clearly represents the charitable Christian heart."[11]

Original sin

[edit]

The scholar of literature Richard Z. Gallant comments that while Tolkien made use of pagan Germanic heroism in his legendarium, and admired its Northern courage, he disliked its emphasis on "overmastering pride". This created a conflict in his writing. The pride of the Elves in Valinor resulted in a fall, analogous to the biblical fall of man. Tolkien described this by saying "The first fruit of their fall was in Paradise [Valinor], the slaying of Elves by Elves"; Gallant interprets this as an allusion to the fruit of the biblical tree of the knowledge of good and evil and the resulting exit from the Garden of Eden.[T 19][12] The leading prideful elf is Fëanor, whose actions, Gallant writes, set off the whole dark narrative of strife among the Elves described in The Silmarillion; the Elves fight and leave Valinor for Middle-earth.[12]

Beowulf

[edit]The passage at the start of the Old English poem Beowulf about Scyld Scefing contains a cryptic mention of þā ("those") who have sent Scyld as a baby in a boat, presumably from across the sea, and to whom Scyld's body is returned in a ship funeral, the vessel sailing by itself. Shippey suggests that Tolkien may have seen in this both an implication of a Valar-like group who behave much like gods, and a glimmer of his Old Straight Road, the way across the sea to Valinor forever closed to mortal Men by the remaking of the world after Númenor's attack on Valinor.[13]

Lost home

[edit]Phillip Joe Fitzsimmons compares The Silmarillion's faraway Valinor, forbidden to Men and lost to the Elves, though it constantly calls to them to return, to Tolkien's fellow-Inkling, Owen Barfield's "lost home". Barfield writes of the loss of "an Edenic relationship with nature", part of his theory that man's purpose is to serve as "the Earth's self-consciousness".[14] Barfield argued that rationalism creates individualism, "unhappy isolation ... [and] the loss of a mutual relationship with nature."[14] Further, Barfield believed that ancient civilisations, as recorded in their languages, had a connection to and inner experience of nature, so that the modern situation represents a loss of that state of grace. Fitzsimmons states that the lost home motif recurs throughout Tolkien's writings. He does not suggest that Barfield influenced Tolkien, but that the ideas of the two men grew from "the same time, place, and even social circle".[14]

Atlantis, Babel

[edit]Kelly and Livingston state that while Aman could be home to Elves as well as Valar, the same was not true of mortal Men. The "prideful"[8] Men of Númenor, imagining they could acquire immortality by capturing the physical lands of Aman, were punished by the destruction of their own island, which is engulfed by the sea, and the permanent removal of Aman "from the circles of the world".[8] Kelly and Livingston note the similarity to the ancient Greek myth of Atlantis, the greatest human civilisation lost beneath the sea; and the resemblance to the biblical tale of the Tower of Babel, the hubristic and "sacrilegious" attempt by mortal men to climb up into God's realm.[8]

Celtic influence

[edit]The scholar of English literature Paul H. Kocher writes that the Undying Lands of the Uttermost West including Eldamar and Valinor, is "so far outside our experience that Tolkien can only ask us to take it completely on faith."[15] Kocher comments that these lands have an integral place both geographically and spiritually in Middle-earth, and that their closest literary equivalents are the imrama Celtic tales from the early Middle Ages. The imrama tales describe how Irish adventurers such as Saint Brendan sailed the seas looking for the "Land of Promise". He notes that it is certain that Tolkien knew these stories, since in 1955 he wrote a poem, entitled Imram, about Brendan's voyage.[15][6]

See also

[edit]- Annwn, the Welsh Otherworld

- Fortunate Isles

References

[edit]Primary

[edit]- ^ Carpenter 2023, #156 to Father R. Murray, SJ, November 1954

- ^ Tolkien 1955, "The Grey Havens", and Appendix B, entry for S.R. 1482 and 1541.

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #249 to Michael Tolkien, October 1963

- ^ Tolkien 1994, "Quendi and Eldar"

- ^ a b c d Tolkien 1977, ch. 5 "Of Eldamar and the Princes of the Eldalië"

- ^ Kept in a folder labelled "Phan, Mbar, Bal and other Elvish etymologies", published in Parma Eldalamberon, 17.

- ^ Parma Eldalamberon, 17, p. 106.

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 9 "Of the Flight of the Noldor"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, ch. 11 "Of the Sun and Moon and the Hiding of Valinor"

- ^ a b c Tolkien 1977, "Valaquenta"

- ^ a b c d e f Tolkien 1977, ch. 1 "Of the Beginning of Days"

- ^ a b Tolkien 1977, ch. 7 "Of the Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 2 "Of Aulë and Yavanna"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 8 "Of the Darkening of Valinor"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 24 "Of the Voyage of Eärendil and the War of Wrath"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, "Akallabêth"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 4 "The Field of Cormallen"

- ^ a b Carpenter 2023, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

Secondary

[edit]- ^ Fauskanger 2022.

- ^ Oberhelman 2013.

- ^ a b c d Fonstad 1991, pp. 1–4 Aman, 6–7 Valinor.

- ^ Tyler 2002, pp. 307–308.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d Shippey 2005, pp. 324–328.

- ^ a b c d e Drout 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kelly & Livingston 2009.

- ^ Dickerson 2007.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 269–272.

- ^ a b c Burns 2005, pp. 152–154.

- ^ a b c Gallant 2014, pp. 109–129.

- ^ Shippey 2022, pp. 166–180.

- ^ a b c Fitzsimmons 2016, pp. 1–8.

- ^ a b c Kocher 1974.

Sources

[edit]- Burns, Marjorie (2005). Perilous Realms: Celtic and Norse in Tolkien's Middle-earth. University of Toronto Press. pp. 152–154 (Elbereth/Varda in Valinor vs Galadriel in Middle-earth, formerly of Valinor). ISBN 978-0802038067.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- Dickerson, Matthew T. (2007). "Paradise". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. CRC Press. pp. 502–503. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- Drout, Michael D. C. (2007). "Eldamar". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. CRC Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- Fauskanger, Helge Kåre (2022). "Valarin - like the glitter of swords". Ardalambion: Of the Tongues of Arda, the invented world of J.R.R. Tolkien. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- Fitzsimmons, Phillip Joe (2016). "Glimpses of lost home in the works of J.R.R. Tolkien and Owen Barfield". Faculty Articles & Research (3).

- Fonstad, Karen Wynn (1991). The Atlas of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Lothlórien. ISBN 0-618-12699-6.

- Gallant, Richard Z. (2014). "Original Sin in Heorot and Valinor". Tolkien Studies. 11 (1): 109–129. doi:10.1353/tks.2014.0019. S2CID 170621644.

- Kelly, A. Keith; Livingston, Michael (2009). "'A Far Green Country: Tolkien, Paradise, and the End of All Things in Medieval Literature". Mythlore. 27 (3).

- Kocher, Paul (1974) [1972]. Master of Middle-earth: The Achievement of J.R.R. Tolkien. Penguin Books. pp. 14–18 and 79–82 (Valinor, Eldamar, Undying Lands, origins in Celtic tales). ISBN 0140038779.

- Oberhelman, David D. (2013) [2006]. "Valinor". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 692–693. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-earth (Third ed.). The Lost Straight Road: HarperCollins. pp. 324–328. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Shippey, Tom (2022). "'King Sheave' and 'The Lost Road'". In Ovenden, Richard; McIlwaine, Catherine (eds.). The Great Tales Never End: Essays in Memory of Christopher Tolkien. Bodleian Library Publishing. pp. 166–180. ISBN 978-1-8512-4565-9.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1994). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The War of the Jewels. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-71041-3.

- Tyler, J. E. A. (2002). The Complete Tolkien Companion. Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-41165-3.