The Old New Land

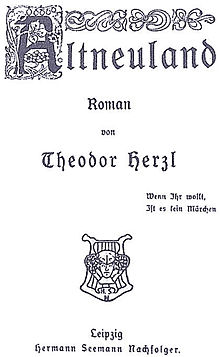

First edition cover | |

| Author | Theodor Herzl |

|---|---|

| Original title | Altneuland |

| Translator | Lotta Levensohn (1997 edition) |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Utopian novel |

| Publisher | Seemann Nachf |

Publication date | 1902 |

| Publication place | Austria-Hungary |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 343 |

| OCLC | 38767535 |

The Old New Land (German: Altneuland; Hebrew: תֵּל־אָבִיב Tel Aviv, "Tel of spring"; Yiddish: אַלטנײַלאַנד) is a utopian novel published in German by Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, in 1902. It was published six years after Herzl's political pamphlet, Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) and expanded on Herzl's vision for a Jewish return to the Land of Israel, which helped Altneuland become one of Zionism's establishing texts. It was translated into Yiddish by Israel Isidor Elyashev (Altnailand. Warsaw, 1902),[1] and into Hebrew by Nahum Sokolow as Tel Aviv (also Warsaw, 1902),[2] a name then adopted for the newly founded city.

Plot introduction

[edit]The novel tells the story of Friedrich Löwenberg, a young Jewish Viennese intellectual, who, tired with European decadence, joins an Americanized Prussian aristocrat named Kingscourt as they retire to a remote Pacific island (it is specifically mentioned as being part of the Cook Islands, near Rarotonga) in 1902. Stopping in Jaffa on their way to the Pacific, they find Palestine a backward, destitute and sparsely populated land, as it appeared to Herzl on his visit in 1898.

Löwenberg and Kingscourt spend the following twenty years on the island, cut off from civilization. As they stop over in Palestine on their way back to Europe in 1923, they are astonished to discover a land drastically transformed. A Jewish organization officially named the "New Society" has since risen as European Jews have rediscovered and re-inhabited their Altneuland, reclaiming their own destiny in the Land of Israel. The country, whose leaders include some old acquaintances from Vienna, is now prosperous and well-populated, boasts a thriving cooperative industry based on state-of-the-art technology, and is home to a free, just, and cosmopolitan modern society. In Haifa, Löwenberg and Reschid Bey meet a group of Jewish leaders who take them on a tour of the country. They visit various cities and settlements, including a kibbutz and a moshav, where they witness the social and economic transformation of the Jewish community. They also learn about the development of new technologies and the establishment of a Jewish university that is at the forefront of scientific research. Arabs have full equal rights with Jews, with an Arab engineer among the New Society's leaders, and most merchants in the country are Armenians, Greeks, and members of other ethnic groups. The duo arrives at the time of a general election campaign, during which a fanatical rabbi establishes a political platform arguing that the country belongs exclusively to Jews and demands non-Jewish citizens be stripped of their voting rights, but is ultimately defeated.

Major themes

[edit]Herzl's novel depicts his vision for the realization of Jewish national emancipation, as put forward in his book Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) published in 1896. Both ideological and utopian, it presents a model society which was to adopt a liberal and egalitarian social model, resembling a modern welfare society.[3] Herzl called his model "Mutualism" and it is based on a mixed economy, with public ownership of the land and natural resources, agricultural cooperatives, welfare, while at the same time encouraging private entrepreneurship. A true modernist, Herzl rejected the European class system, yet remained loyal to Europe's cultural heritage.

Rather than imagining the Jews in Altneuland as speaking mainly Hebrew, the society is multilingual. While the language question is not discussed in detail, it appears that Yiddish is the main vernacular language and German the main written language. European customs are reproduced, such as going to the opera and enjoying the theatre. While Jerusalem is the capital, with the seat of parliament ("Congress") and the Jewish Academy, the country's industrial center is the modern city of Haifa.

Herzl saw the potential of Haifa Bay for constructing a modern deep-water port. As envisioned by Herzl, "All the way from Acco to Mount Carmel stretched what seemed to be one great park".

Herzl's depiction of Jerusalem includes a rebuilt Jerusalem Temple. However, in his view, the Temple did not need to be built on the precise site where the old Temple stood and which is now taken up by the Muslim Al-Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock - very sensitive holy sites. By locating the Temple at a different Jerusalem location, the Jewish state envisioned by Herzl avoids the extreme tension over this issue experienced in the actual Israel. Also, worship at the Temple envisioned by Herzl does not involve animal sacrifice, which was the main form of worship at the ancient Jerusalem Temple. Rather, the Temple depicted in Alteneuland is essentially just an especially big and ornate synagogue, holding the same kind of services as any other synagogue.

The country envisioned in the book is not involved in any wars and does not maintain any armed forces. As explained in the book, the founders took care to get the consent of all European powers for their enterprise and not get entangled in any inter-power rivalry. As for the country's Arab inhabitants, the book's single Arab character, Rashid Bey, explains that the Arabs saw no reason to oppose the influx of Jews, who "developed the country and raised everybody's standard of living".

As noted in a lengthy flashback detailing, a Zionist Charter Company named "The New Society for the Colonization of Palestine" was able to get "autonomous rights to the regions which it was to colonize" in return for paying the Turkish Government £2,000,000 sterling in cash, plus £50,000 a year and one fourth of its net annual profits. In theory, "The ultimate sovereignty" remained "reserved to the Sultan"; in practice, however, the entire detailed description given in the book does not mention even the slightest vestige of an Ottoman administration or of any Ottoman influence in the life of the country.

The territorial extent of the envisioned Old New Land is clearly far greater than that of the actual Israel, even including its 1967 conquests. Tyre and Sidon in the present Lebanon are among its port cities. Kuneitra - actually at the extreme end of the Golan Heights which Israel captured in 1967, and handed back to Syria in 1973 - was in Herzl's vision a prosperous way station on a railway extending much further eastwards, evidently controlled by "The New Society". In another reference are mentioned "the cities along the railway to the Euphrates - Damascus and Tadmor" (the latter a rebuilt Palmyra).

Having obtained the general concession from the Ottoman government, "The New Society" set out to buy up the land from its private owners. As depicted in the book, the sum of £2,000,000 was set aside to pay the land owners. A single agent traveled the land and within a few months secured to "The New Society" ownership of virtually its entire land area, evidently encountering no opposition and no unwillingness to sell.

The lost tribe of Dan appears towards the end of Theodore Herzl's Altneuland, where the protagonist, Friedrich Löwenberg, and his friend Reschid Bey, discover a group of people who are descendants of the ancient tribe of Dan, living in isolation on a remote island in the Red Sea. The significance of this episode lies in its metaphorical representation of the renewal of the Jewish people, emphasizing the importance of preserving and building upon their rich historical legacy. The discovery of the lost tribe underscores Herzl's belief in the importance of Jewish self-determination and the need for a Jewish state in Palestine, based on a deep and abiding connection to Jewish history and culture. Overall, the episode with the lost tribe of Dan serves as a powerful symbol of Jewish identity and the enduring strength of the Jewish people.

Historical context

[edit]The novel was significant in the establishment of Zionist ideas as it was published in the time period of the First Aliyah. Altneuland also reflects Herzl's belief in the importance of technology and progress. The Jewish state in the novel is a highly advanced society, where scientific and technological innovation is celebrated and valued. This reflects Herzl's belief that the Jewish people needed to embrace modernity in order to succeed in the modern world.[4][page needed][5] Additionally, Altneuland also highlights Herzl's commitment to social equality and the idea of a multicultural Jewish society. The novel portrays a Jewish state where Jews and Arabs live together in harmony, reflecting Herzl's belief in the importance of coexistence and mutual respect between different communities.[6]

Altneuland, at the time of the rise of Zionism as a political movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, saw the emergence of a new form of Jewish nationalism that sought to establish a Jewish state in Palestine began to prevail. The Zionist movement was fueled by a range of factors: the aggressive rise of anti-Semitism in Europe, the unifying sense of Jewish identity and solidarity that followed, and the desire for a homeland where Jews could live free from persecution and not be a minority in their society inspired a new wave of Zionism led by individuals like Theodore Hertzl.[7]

The novel directly reflected Herzl's political philosophy represented through a new form, literature. The novel presented a modern, democratic, and multicultural Jewish state, which was a departure from the traditional religious and cultural identity of the Jewish people.[8] Herzl emphasized the importance of Jewish self-determination and the need for a Jewish state to ensure the safety of the Jewish people. Herzl believed that the Jewish community was a nation and needed a state of its own to survive in the modern world. This idea became a pillar of Zionism and was later instrumental in the need for the establishment of the State of Israel.[9]

Legacy

[edit]

The book was immediately translated into Hebrew by Nahum Sokolow, who gave it the poetic title "Tel Aviv", using tel ('ancient mound') for 'old' and aviv ('spring') for 'new'.[10] The name as such appears in the Book of Ezekiel, where it is used for a place in Babylonia to which the Israelites had been exiled (Ezekiel 3:15). The Hebrew title of the book was chosen by Jewish residents as the name for the newly purchased twelve acres of sand dunes, north of Jaffa, established in 1909 under a company name "Ahuzat Bayit (lit. "homestead") society", and with the financial assistance of the Jewish National Fund. The town was originally named Ahuzat Bayit. On 21 May 1910, the name Tel Aviv was adopted. Eventually, Tel Aviv would become known as "the first [modern] Hebrew city" and a central economic and cultural hub of Israel.

Additionally, the first Hebrew edition of the Herzl biography that was written after 1948, and published by Alex Bein in 1960, reflected historical viewpoint changes based on the summary of The Old New Land. In the summary, the outline of Altneuland was significantly shorter than that of the previously published 1938 copy.[11] The shortened summary did not include details of the interaction between Herzl's Altneuland Palestine and the ruling Ottoman empire. However, it is important to note that many other references to Herzl's Altneuland Palestine following the establishment of a Jewish state do not include this information as well.

Herzl's friend Felix Salten visited Palestine in 1924 and saw how Herzl's dream was coming true. Next year, Salten gave his travel book the title Neue Menschen auf alter Erde (“New People on Old Soil”),[12] and both the title of this book and its contents allude to Herzl's Altneuland.[13]

- First Hebrew edition of the book, printed in 1902

Publication details

[edit]- 1902, Germany, Hermann Seemann Nachfolger, Leipzig, hardback (First edition) (as Altneuland in German)

- 1941, US, Bloch Publishing, hardback (translated by Lotta Levensohn)

- 1961, Israel, Haifa Publishing, paperback (as Altneuland in German)

- 1987, US, Random House (ISBN 0-910129-61-4), paperback

- 1997, US, Wiener (Markus) Publishing (ISBN 1-55876-160-8), paperback

References

[edit]- ^ "Altneuland" – First Yiddish Edition – Warsaw, 1902. Kedem Auction House, 2018

- ^ "Tel Aviv" – First Hebrew Translation of Theodor Herzl's "Altneuland". Kedem Auctions,2016

- ^ "1902: Theodor Herzl Finishes His Novel 'Old-New Land'" – via Haaretz.

- ^ Avineri, Shlomo (4 April 2017). The making of modern Zionism: the intellectual origins of the Jewish state. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-09479-0. OCLC 1020298546.

- ^ N, Davidovitch; R, Seidelman (2003). "Herzl's Altneuland: Zionist utopia, medical science and public health". Korot. 17: 1–21, ix. ISSN 0023-4109. PMID 17153576.

- ^ Laqueur, Walter (2003). A history of Zionism. European Jewish Publications Society (3rd ed.). London: Tauris Parke. pp. 210–211. ISBN 978-0-85771-325-4. OCLC 842932838.

- ^ Charry, Elias (1963). "Review of The Zionist Idea". Jewish Social Studies. 25 (2): 157–159. ISSN 0021-6704. JSTOR 4465995.

- ^ "Altneuland (Theodor Herzl)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- ^ Shapira, Anita (2015). Israel: a history. Anthony Berris. London. ISBN 978-1-78022-739-9. OCLC 898155397.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Avineri, Shlomo: Zionism According to Theodor Herzl. Haaretz (20 December 2002). "Altneuland is [...] a utopian novel written by [...] Theodor Herzl, in 1902. [...] The year it was published, the novel was translated into Hebrew by Nahum Sokolow, who gave it the poetic name ‘Tel Aviv’ (which combines the archaeological term tel and the word for the season of spring)."

- ^ Shumsky, Dimitry (2014). ""This Ship Is Zion!": Travel, Tourism, and Cultural Zionism in Theodor Herzl's Altneuland". Jewish Quarterly Review. 104 (3): 471–493. doi:10.1353/jqr.2014.0027. ISSN 1553-0604. S2CID 154255752.

- ^ Salten, Felix (1925). Neue Menschen auf alter Erde: Eine Palästinafahrt (in German). Wien: Paul Zsolnay Verlag. LCCN 25023844.

- ^ Eddy, Beverley Driver (2010). Felix Salten: Man of Many Faces. Riverside (Ca.): Ariadne Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-1-57241-169-2.

External links

[edit]- Altneuland by Theodor Herzl, English translation at the Wayback Machine (archived December 6, 2008)

- Full text translation at Jewish Virtual Library

- Dreaming of Altneuland. The Economist, December 21, 2000.

- The Herzl Museum in Jerusalem