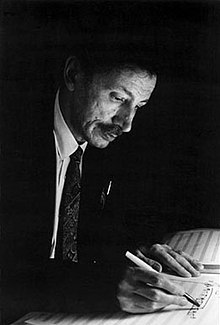

Alan Hovhaness

Alan Hovhaness (/hoʊˈvɑːnɪs/;[1] March 8, 1911 – June 21, 2000) was an American composer. He was one of the most prolific 20th-century composers, with his official catalog comprising 67 numbered symphonies (surviving manuscripts indicate over 70) and 434 opus numbers.[2] The true tally is well over 500 surviving works, since many opus numbers comprise two or more distinct works.

The Boston Globe music critic Richard Buell wrote: "Although he has been stereotyped as a self-consciously Armenian composer (rather as Ernest Bloch is seen as a Jewish composer), his output assimilates the music of many cultures. What may be most American about all of it is the way it turns its materials into a kind of exoticism. The atmosphere is hushed, reverential, mystical, nostalgic."[3]

Early life

[edit]He was born as Alan Vaness Chakmakjian (Armenian: Ալան Յարութիւն Չաքմաքճեան)[4] in Somerville, Massachusetts, to Haroutioun Hovanes Chakmakjian (an Armenian chemistry professor at Tufts College who had been born in Adana, Turkey) and Madeleine Scott (an American of Scottish descent who had graduated from Wellesley College). When he was five, his family moved from Somerville to Arlington, Massachusetts. A Hovhaness family neighbor said his mother had insisted on moving from Somerville because of discrimination against Armenians there.[5] After her death (on October 3, 1930), he began to use the surname "Hovaness" in honor of his paternal grandfather,[citation needed] and changed it to "Hovhaness" around 1944. He stated the name change from the original Chakmakjian reflected the desire to simplify his name because "nobody ever pronounced it right".[6] However, Hovhaness' daughter Jean Nandi has written in her book Unconventional Wisdom,[7] "My father's name at the time of my birth was 'Hovaness', pronounced with accent on the first syllable. His original name was 'Chakmakjian', but in the 1930s he wanted to get rid of the Armenian connection and so changed his name to an Americanized version of his middle name. Some years later, deciding to re-establish his Armenian ties, he changed the spelling to 'Hovhaness', accent on the second syllable; this was the name by which he later became quite famous."

Hovhaness was interested in music from a very early age. At the age of four, he wrote his first composition, a cantata in the early Italian style inspired by a song of Franz Schubert. His family was concerned about his late-night composing and about the financial future he could possibly have as an artist. He decided for a short time to pursue astronomy, another of his early loves.[8] The fascination of astronomy remained with him through his entire life and composing career, with many works titled after various planets and stars.

Hovhaness's parents soon supported their son's precocious composing, and set up his first piano lessons with a neighborhood teacher. Hovhaness continued his piano studies with Adelaide Proctor and then Heinrich Gebhard. By age 14 he decided to devote himself to composition. Among his early musical experiences were Baptist hymns and recordings of Gomidas Vartabed, an eminent Armenian composer. He composed two operas during his teenage years which were performed at Arlington High School, and composer Roger Sessions took an interest in his music during this time. Following his graduation from high school in 1929, he studied with Leo Rich Lewis at Tufts and then under Frederick Converse at the New England Conservatory of Music. In 1932, he won the Conservatory's Samuel Endicott prize for composition with his Sunset Symphony (elsewhere entitled Sunset Saga).

In July 1934, Hovhaness traveled with his first wife, Martha Mott Davis, to Finland to meet Jean Sibelius, whose music he had greatly admired since childhood. The two continued to correspond for the next twenty years. In 1935, Hovhaness named his daughter and only child from his first marriage Jean Christina Hovhaness after Jean Christian Sibelius, her godfather and Hovhaness's friend for three decades.

Destruction of early works

[edit]During the 1930s and 1940s, Hovhaness famously destroyed many of his early works. He later claimed that he had burned at least 1,000 different pieces, a process that took at least two weeks;[8] elsewhere he claimed to have destroyed around 500 scores totaling as many as a thousand pages.[9] In an interview with Richard Howard, he stated that the decision was based primarily on Sessions' criticism of his works of that period, and that he wanted to make a new start in composition.[8]

Musical career

[edit]"Armenian Period"

[edit]Hovhaness became interested in Armenian culture and music in 1940 as organist for the St. James Armenian Apostolic Church in Watertown, Massachusetts, remaining in this position for about ten years. In 1942, he won a scholarship at Tanglewood to study in Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů's master class. During a seminar in composition, while a recording of Hovhaness's first symphony was being played, Aaron Copland talked loudly in Spanish to Latin-American composers in the room; and at the end of the recording Leonard Bernstein went to the piano, played a melodic minor scale and rebuked the work as "cheap ghetto music".[10] Apparently angered and distraught by this experience, he left Tanglewood early, abandoning his scholarship and again destroying a number of his works in the aftermath of that major disappointment.[11]

The next year he devoted himself to Armenian subject matter,[12] in particular using modes distinctive to Armenian music, and continued in this vein for several years, achieving some renown and the support of other musicians, including radical experimentalist composer John Cage and choreographer Martha Graham, all the while continuing as church organist.

Beginning in the mid-1940s, Hovhaness and two artist friends, Hyman Bloom and Hermon di Giovanno, met frequently to discuss spiritual and musical matters. All three had a strong interest in Indian classical music, and brought many well known Indian musicians to Boston to perform. During this period, Hovhaness learned to play the sitar, studying with amateur Indian musicians living in the Boston area. Around 1942, Bloom introduced Hovhaness to Yenovk Der Hagopian, a fine singer of Armenian and Kurdish troubadour songs, whose singing inspired Hovhaness.

In one of several applications for a Guggenheim fellowship (1940), Hovhaness presented his credo at the time of application:

- I propose to create a heroic, monumental style of composition simple enough to inspire all people, completely free from fads, artificial mannerisms and false sophistications, direct, forceful, sincere, always original but never unnatural. Music must be freed from decadence and stagnation. There has been too much emphasis on small things while the great truths have been overlooked. The superficial must be dispensed with. Music must become virile to express big things. It is not my purpose to supply a few pseudo-intellectual musicians and critics with more food for brilliant argumentation, but rather to inspire all mankind with new heroism and spiritual nobility. This may appear to be sentimental and impossible to some, but it must be remembered that Palestrina, Handel and Beethoven would not consider it either sentimental or impossible. In fact, the worthiest creative art has been motivated consciously or unconsciously by the desire for the regeneration of mankind.[13]

Lou Harrison reviewed a 1945 concert of Hovhaness' music, which included his 1944 concerto for piano and strings, entitled Lousadzak:

- There is almost nothing occurring most of the time but unison melodies and very lengthy drone basses, which is all very Armenian. It is also very modern indeed in its elegant simplicity and adamant modal integrity, being, in effect, as tight and strong in its way as a twelve-tone work of the Austrian type. There is no harmony either, and the brilliance and excitement of parts of the piano concerto were due entirely to vigor of idea. It really takes a sound musicality to invent a succession of stimulating ideas within the bounds of an unaltered mode and without shifting the home-tone.[14]

However, as before, there were also critics:

- The serialists were all there. And so were the Americanists, both Aaron Copland's group and Virgil [Thomson]'s. And here was something that had come out of Boston that none of us had ever heard of and was completely different from either. There was nearly a riot in the foyer [during intermission] — everybody shouting. A real whoop-dee-doo.[15]

Lousadzak was Hovhaness's first work to make use of an innovative technique he called "spirit murmur", an early example of aleatoric music inspired by a vision of Hermon di Giovanno.[16] The technique, essentially similar to the 1960s ad libitum aleatory of Lutoslawski, involves instruments repeating phrases in uncoordinated fashion, producing a complex "cloud" or "carpet" of sounds.[16]

In the mid-1940s, Hovhaness' stature in New York was helped considerably by members of the immigrant Armenian community who sponsored several high-profile concerts of his music. This organization, the Friends of Armenian Music Committee, was led by Hovhaness's friends Dr. Elizabeth A. Gregory, the Armenian American piano/violin duo Maro Ajemian and Anahid Ajemian, and later Anahid's husband, pioneering record producer and subsequent Columbia Records executive George Avakian. Their help led directly to many recordings of Hovhaness' music appearing in the 1950s on MGM and Mercury records, placing him firmly on the American musical landscape.

In May and June 1946,[17] while staying with an Armenian family, Hovhaness composed Etchmiadzin, an opera on an Armenian theme, which was commissioned by a local Armenian church.

Conservatory years

[edit]In 1948 he joined the faculty of the Boston Conservatory, teaching there until 1951. His students there included the jazz musicians Sam Rivers and Gigi Gryce.

Relocation to New York

[edit]In 1951 Hovhaness moved to New York City, where he became a full-time composer. Also that year (starting on August 1), he worked for the Voice of America, first as a script writer for the Armenian section, then as director of music, composer and musical consultant for the Near East and Transcaucasian sections. He eventually lost this job (along with much of the other staff) when Dwight D. Eisenhower succeeded Harry S. Truman as U.S. president in 1953. From this time on, he branched out from Armenian music, adopting styles and material from a wide variety of sources. As documented in 1953 and 1954, he received Guggenheim Fellowships in composition. He wrote the score for the Broadway play The Flowering Peach by Clifford Odets in 1954, a ballet for Martha Graham (Ardent Song, also in 1954), and two scores for NBC documentaries on India and Southeast Asia (1955 and 1957). Also during the 1950s, he composed for productions at The Living Theatre.

His biggest breakthrough till then came in 1955, when his Symphony No. 2, Mysterious Mountain, was premiered by Leopold Stokowski in his debut with the Houston Symphony,[18] although the idea that Mysterious Mountain was commissioned for that orchestra is a common misconception.[19] That same year, MGM Records released recordings of a number of his works. Between 1956 and 1958, at the urging of Howard Hanson, an admirer of his music, he taught summer sessions at the Eastman School of Music long presided over by Hanson. One of Hovhaness's students there was Dominick Argento, who described him as "by far the most spontaneous and prolific composer I ever knew."[20]

Trips to Asia

[edit]From 1959 through 1963 Hovhaness conducted a series of research trips to India, Hawaii, Japan and South Korea, investigating the ancient traditional musics of these nations and eventually integrating elements of these into his own compositions. His study of Carnatic music in Madras, India (1959–60), during which he collected over 300 ragas, was sponsored by a Fulbright fellowship. While in Madras, he learned to play the veena and composed a work for Carnatic orchestra entitled Nagooran, inspired by a visit to the dargah at Nagore, which was performed by the South Indian Orchestra of All India Radio Madras and broadcast on All-India Radio on February 3, 1960. He compiled a large amount of material on Carnatic ragas in preparation for a book on the subject, but never completed it.

He then studied Japanese gagaku music (learning the wind instruments hichiriki, shō, and ryūteki) in the spring of 1962 with Masatoshi Shamoto in Hawaii, and a Rockefeller Foundation grant allowed him further gagaku studies with Masataro Togi in Japan (1962–63). Also while in Japan, he studied and played the nagauta (kabuki) shamisen and the jōruri (bunraku) shamisen. In recognition of the musical styles he studied in Japan, he wrote Fantasy on Japanese Woodprints, Op. 211 (1965), a concerto for xylophone and orchestra.[21]

In 1963 he composed his second ballet score for Martha Graham, entitled Circe.

He and his then wife then set up a record label devoted to the release of his own works, Poseidon Society. Its first release was in 1963, with around 15 discs following over the next decade. Following their divorce, the wife was granted ownership of the label but then either sold or transferred rights to this catalog to Crystal Records.

In 1965, as part of a U.S. government-sponsored delegation, he visited Russia as well as Soviet-controlled Georgia and Armenia, the only time he visited his paternal ancestral homeland. While there, he donated his handwritten manuscripts of harmonized Armenian liturgical music to the Yeghishe Charents State Museum of Arts and Literature in Yerevan.

In the mid-1960s he spent several summers touring Europe, living and working much of the time in Switzerland.

World view

[edit]Hovhaness stated in a 1971 interview in Ararat magazine:[4]

We are in a very dangerous period. We are in danger of destroying ourselves, and I have a great fear about this ... The older generation is ruling ruthlessly. I feel that this is a terrible threat to our civilization. It's the greed of huge companies and huge organizations which control life in a kind of a brutal way ... It's gotten worse and worse, somehow, because physical science has given us more and more terrible deadly weapons, and the human spirit has been destroyed in so many cases, so what's the use of having the most powerful country in the world if we have killed the soul. It's of no use.

Later life

[edit]Hovhaness was inducted into the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1951), and received honorary D.Mus. degrees from the University of Rochester (1958), Bates College (1959) and the Boston Conservatory (1987). He moved to Seattle in the early 1970s, where he lived for the rest of his life. In 1973, he composed his third and final ballet score for Martha Graham: Myth of a Voyage, and over the next twenty years (between 1973 and 1992) he produced no fewer than 37 new symphonies.

He created a major work, The Rubaiyat, A Musical Setting in 1975, which was for narrator and orchestra and has been twice recorded. Rubaiyat refers to the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Persian mathematician, astronomer, and poet.[22] The text consisted of a dozen of the English quatrains from the translation by Edward FitzGerald.

Continuing his interest in composing for Asian instruments, in 1981, at the request of Lou Harrison, he composed two works for Indonesian gamelan orchestra which were premiered by the gamelan at Lewis & Clark College, under the direction of Vincent McDermott.

Hovhaness was survived by his sixth wife, the coloratura soprano Hinako Fujihara Hovhaness (1932–2022),[23] who administered the Hovhaness-Fujihara music publishing company, [1] as well as a daughter (from his first wife), harpsichordist Jean Nandi (b. 1935). He died in 2000.

Hovhaness archives

[edit]Significant archives of Hovhaness materials, comprising scores, sound recordings, photographs and correspondence are located at several academic centers, including Harvard University, the University of Washington, the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., the Armenian Cultural Foundation in Arlington, Massachusetts, and Yerevan’s State Museum of Arts and Literature in Armenia.

Partial list of compositions

[edit]- 1936 (rev. 1954) – Prelude and Quadruple Fugue (orchestra), Op. 128

- 1936 – Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 17

- 1936 – Exile (Symphony No. 1), Op. 17, No.2

- 1940 – Psalm and Fugue, Op. 40a

- 1940 – Alleluia and Fugue, Op. 40b

- 1944 – Lousadzak (Concerto for piano and strings), Op. 48

- 1945 – Mihr (for two pianos)

- 1946 – Prayer of St. Gregory, Op. 62b, for trumpet and strings (interlude from the opera Etchmiadzin)

- 1947 – Arjuna (Symphony No. 8) for piano, timpani and orch., Op. 179

- 1948 – Artik Concerto for Horn and String Orchestra, Op. 78

- 1949–50 – St. Vartan Symphony (No. 9), Op. 180

- 1950 – Janabar (Sinfonia Concertante for piano, trumpet, violin and strings), Op. 81

- 1951 – Khaldis, Op. 91, for piano, four trumpets, and percussion

- 1953 – Concerto No. 7 (Orchestra), Op. 116

- 1954 – Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra, Op. 123, No. 3

- 1955 – Mysterious Mountain (Symphony No. 2), Op. 132

- 1957 – Symphony No. 4, Op. 165

- 1958 – Meditation on Orpheus, Op. 155

- 1958 – Magnificat (SATB soli, SATB choir and orchestra), Op. 157

- 1959 – Symphony No. 6, Celestial Gate, Op. 173

- 1959 – Symphony No. 7, Nanga Parvat, for symphonic wind band, Op. 178

- 1960 – Symphony No. 11, All Men are Brothers, Op. 186

- 1963 – The Silver Pilgrimage (Symphony No. 15), Op. 199

- 1965 – Fantasy on Japanese Woodprints for xylophone and orchestra, Op. 211

- 1967 – Fra Angelico, Op. 220

- 1968 – Mountains and Rivers without End, Chamber Symphony for 10 players, Op. 225

- 1969 – Lady of Light (soli, chorus, and orch), Op. 227

- 1969 – Shambala, Concerto for violin, sitar, and orchestra, Op. 228

- 1970 – And God Created Great Whales (taped whale songs and orchestra), Op. 229

- 1970 – Symphony Etchmiadzin (Symphony No. 21), Op. 234

- 1970 – Symphony No. 22, City of Light, Op. 236

- 1971 – Saturn Op. 243 for soprano, clarinet, and piano

- 1973 – Majnun Symphony (Symphony No. 24), Op. 273

- 1979 – Guitar Concerto No. 1, Op. 325

- 1982 – Symphony No. 50, Mount St. Helens, Op. 360

- 1983 - Symphony No. 53, Star Dawn, Op. 377

- 1985 – Guitar Concerto No. 2 for guitar and strings, Op. 394

- 1985 – Symphony No. 60, To the Appalachian Mountains, Op. 396

- 1992 – Symphony No. 66, Hymn to Glacier Peak, Op. 428

Films

[edit]Films about Alan Hovhaness

[edit]- 1984 – Alan Hovhaness. Directed by Jean Walkinshaw, KCTS-TV, Seattle.

- 1986 – Whalesong. Directed by Barbara Willis Sweete, Rhombus Media.

- 1990 – The Verdehr Trio: The Making of a Medium. Program 1: Lake Samish Trio/Alan Hovhaness. Directed by Lisa Lorraine Whiting, Michigan State University.

- 2006 – A Tribute to Alan Hovhaness. Produced by Alexan Zakyan, Hovhaness Research Centre, Yerevan, Armenia.

Films with scores by Alan Hovhaness

[edit]- 1956 – Narcissus. Directed by Willard Maas.

- 1957 – Assignment: Southeast Asia. NBC-TV documentary.

- 1962 – Pearl Lang and Francisco Moncion dance performance: Black Marigolds. From the CBS television program Camera Three, presented in cooperation with the New York State Education Department. Directed by Nick Havinga.

- 1966 – Nehru: Man of Two Worlds. From The Twentieth Century series; reporter: Walter Cronkite. A presentation of CBS News.

- 1973 – Tales From a Book of Kings: The Houghton Shah-Nameh. New York, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Time-Life Multimedia.

- 1982 – Everest North Wall. Directed by Laszlo Pal.

- 1984 – Winds of Everest. Directed by Laszlo Pal.

- 2005 – I Remember Theodore Roethke. Produced and edited by Jean Walkinshaw, KCTS Public Television, Seattle.

Notable students

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Hovhaness". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ The number of opus numbers was identified as 434 by Kenneth Page in a review in Limelight magazine (Australia), May 2007, p. 55.

- ^ Richard Buell, "Sinfo Nova remembers Hovhaness", The Boston Globe, February 2, 1987.

- ^ a b Julia Michaelyan, "An Interview with Alan Hovhaness", Ararat 45, v. 12, no. 1 (Winter 1971), pp. 19–31. Reprinted on The Alan Hovhaness Website.

- ^ Martin Berkofsky "An Interview with Jack Johnston" Archived 2010-08-15 at the Wayback Machine (transcribed 2008), Alan Hovhaness International Research Center

- ^ Lynn Johnston, "Alan Hovhaness: An Interview with a Master Composer", The Arlington (MA) Advocate (July 5, 1984), and The Armenian Mirror-Spectator, vol. 52, no. 1, issue 2843 (July 21, 1984). Available on CD (copyright 2000) at Robbins Library, Arlington, MA, and at the Library of Congress.

- ^ Jean Nandi, Unconventional Wisdom: A Memoir ([Berkeley, California]: Author, 2000), p. 1

- ^ a b c Richard Howard, "Hovhaness Interview: Seattle 1983", The Alan Hovhaness Website, 2005 (Accessed 23 February 2010).

- ^ Cole Gagne, Soundpieces 2: Interviews with American Composers (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1993), p. 121. ISBN 0-8108-2710-7.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (November 4, 2011). "A Composer Echoes in Unexpected Places". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Alan Hovhaness; Prolific Composer". Los Angeles Times. June 23, 2000. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Abramson, Maya Elise (2015). "Alan Hovhaness's Armenian period: The functional use of melody in a non-harmonic context". Arminda Whitman. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ Shirodkar, Marco. "Alan Hovhaness Biographical Summary". The Alan Hovhaness Web Site. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- ^ Lou Harrison, "Alan Hovhaness Offers Original Compositions", New York Herald Tribune (June 18, 1945), p. 11.

- ^ Leta E. Miller and Frederic Lieberman, Lou Harrison: Composing a World (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1998). ISBN 0-19-511022-6.[page needed]

- ^ a b Richard Howard (2005). "Hovhaness Interview: Seattle 1983". The Alan Hovhaness Website.

- ^ "Alan Hovhaness List of Works by Opus Number". www.hovhaness.com. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ^ Smith, William Ander (1990). The Mystery of Leopold Stokowski. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 2054. ISBN 0838633625.

- ^ S., Marco. "Alan Hovhaness | Symphonies Nos. 1–14 Including Mysterious Mountain". www.hovhaness.com. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- ^ Argento, Dominick (2004). Catalogue Raisonné As Memoir. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-8166-4505-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Burton, Anthony (January 20, 2012). "Hovhaness: Symphony No. 22 (City of Light); Exile Symphony; Bagatelle No. 1; Bagatelle No. 2; Bagatelle No. 3; Bagatelle No. 4; Fantasy on Japanese Woodprints; Prayer of St Gregory; String Quartet No. 4". BBC Music Magazine. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ "KHAYYAM, OMAR xiii. Musical Works Based On The – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-03-24.

- ^ Obituary of Hinako Hovhaness

Further reading

[edit]- Howard, Richard (1983). The Works of Alan Hovhaness: A Catalog, Opus 1 – Opus 360. Pro Am Music Resources. ISBN 0-912483-00-8.

- Kostelanetz, Richard (1989). On Innovative Music(ian)s. New York: Limelight Editions.

- Malina, Judith (1984). The Diaries of Judith Malina, 1947–1957. New York: Grove Press, Inc. ISBN 0-394-53132-9.

- Rosner, Arnold, and Vance Wolverton (2001). "Hovhaness [Hovaness], Alan [Chakmakjian, Alan Hovhaness]". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

External links

[edit]| Archives at | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| How to use archival material |

- The Alan Hovhaness website

- The Alan Hovhaness Collection (at the Armenian Cultural Foundation Archives, Arlington, Massachusetts)

- Alan Hovhaness in conversation with Bruce Duffie

- An Overview of the Music of Alan Hovhaness on CD

- Listening

- Other Minds Archive: "The World of Alan Hovhaness" from KPFA's Ode To Gravity series, aired 28 January 1976; includes an interview with the composer by Charles Amirkhanian recorded in late 1975

- Art of the States: Alan Hovhaness Lousadzak, op. 48 (1944)

- 1911 births

- 2000 deaths

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century American classical composers

- 20th-century American classical pianists

- American ballet composers

- American contemporary classical composers

- American male classical composers

- American male classical pianists

- American people of Armenian descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- Classical musicians from Massachusetts

- Composers for carillon

- Contemporary classical music performers

- Musicians from Somerville, Massachusetts

- People from Arlington, Massachusetts

- Pupils of Bohuslav Martinů

- Shō players

- Tufts University alumni