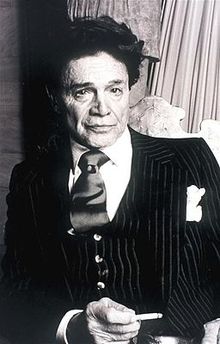

Alexander Iolas

Alexander Iolas | |

|---|---|

Alexander Iolas | |

| Born | Constantine Coutsoudis March 26, 1908 Alexandria, Egypt |

| Died | June 8, 1987 (aged 79) New York City, US |

| Citizenship | American |

| Occupation(s) | Ballet dancer, gallerist, art dealer and collector |

Alexander Iolas (Greek: Αλέξανδρος Ιόλας) (March 26, 1908 – June 8, 1987) was an Egyptian-born Greek-American art gallerist and significant collector of classical and modern art works, who advanced the careers of René Magritte, Andy Warhol and many other artists.[1] He established the modern model of the global art business, operating successful galleries in Paris, Geneva, Milan and New York.[2]

Early life

[edit]Iolas was born on March 26, 1908, in Alexandria, Egypt, under the name Constantine Coutsoudis (Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Κουτσούδης), to a well-off family of cotton traders.[3] He graduated from Averofeio highschool, where he was a pupil of Glaukos Alithersis, a Cypriot physical education teacher and poet, who introduced him to Constantine Cavafy.

Career

[edit]From an early age, Iolas showed an inclination towards the arts and consequently, in 1928, he moved to Athens, Greece. There, Iolas began to associate with an artistic circle of people such as Kostis Palamas and Angelos Sikelianos, who would play a mentoring role in his life, as well as Eva Palmer-Sikelianos. It was in Athens that Iolas took his first steps in dancing.

In 1930, upon the urging of Dimitris Mitropoulos, Iolas moved to Berlin where he devoted himself to dance studies. He attended the school of Tatjana and Victor Gsovsky and participated in the Salzburg Festival in 1931 and 1932.

In November 1932, Iolas moved to Paris where he continued studying ballet with some well-known teachers, and also attended art classes at the Sorbonne.[4]

In 1935, Iolas went to New York. There, on December 14, 1935, he signed a contract with the Ballet Productions dance troupe and made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera House, dancing in La Traviata.

On November 19, 1945, Iolas became a naturalized American citizen and signed as Constantine Coutsoudis. His official name change took place later. The restructuring of Iolas' name was an invention of his; he had already appeared as 'Jolas Coutsoudis' in theatrical programs since 1931, long before he went to America. The name 'Iolas' gradually replaced his actual surname as it was more euphonic, with only two-syllables and therefore easier to pronounce. Mainly, though, it was symbolic since it was associated with Iolaus, a glorious figure of Greek Mythology. 'Alexander' is also a glorious name, closely related to the city in which Iolas was born.

In 1945, Iolas decided to give up dancing and explore a way to transition to art. It was rumored that this transition was due to an injury, but the truth is that, at 37 years old, he considered himself to be "too old for dancing."[5]

On September 1, 1945, Iolas's first gallery, the Hugo Gallery, was officially established in New York, named in honor of François Hugo, the last spouse of Donna Maria Ruspoli who was a close friend of Iolas. He started by exhibiting works of European surrealist artists, such as René Magritte, Max Ernst, Giorgio de Chirico, and Victor Brauner. There, in 1952, Iolas also presented Andy Warhol's first exhibition. He later collaborated with the New Realists (Niki de Saint Phalle, Jean Tinguely, Martial Raysse, et al.), with Arte Povera artists (Jannis Kounellis, Pino Pascali et al.) and many others. In 1954, the gallery expanded and was renamed 'Alexander Iolas, Inc'.

Iolas was one of the pioneers in the development of a "network" of art galleries, satellites of a central art gallery, by opening new Alexander Iolas Galleries in Geneva (1963), Paris (1964), Milan (1966), Zürich, Madrid and Rome. At the same time, he promoted Greek artists abroad, such as Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas, Vagis, Moralis and Tsarouchis. He also collaborated with the younger generation of Greek artists, such as Kostas Tsoklis, Pavlos, Takis, Akrithakis, Fassianos and Mara Karetsos, who had already started a career abroad.

Iolas also published art catalogues, prefaced by, among others, André Breton and Pierre Restany, as well as collectible books of artists and poets in a limited number of copies (Max Ernst, Giannis Ritsos, Odysseas Elytis et al.). He donated artworks to large museums, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Georges Pompidou Center in Paris (donations in 1977), as well as the National Art Gallery of Athens (donation in 1971).[6]

Having obtained worldwide fame, Iolas often said that he would return to Greece in order to contribute to the progress of its artistic life. The fall of the Greek junta in 1974 had paved the way for this. He gradually closed down all his galleries but the one in New York, thus keeping his promise to Marx Ernst, to stop when he died. The fact that, during the '70s, many artists from the old guard died, people by whom Iolas had been nurtured and for whom he had deep love and respect, must have also played a significant role in his decision. In Greece, he collaborated with various galleries, such as the Zoumboulakis–Iolas Gallery, Medusa, Vicky Drakos, Athens Art Gallery, Skoufa et al.

In 1982 he commissioned Warhol to do a series of colourful silkscreen prints of a Roman-era bronze head of Alexander the Great to correspond with the blockbuster exhibition of ancient art and artefacts The Search for Alexander.[7] In 1984, Iolas donated 47 works of contemporary art from his personal collection to the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art, while he promised to donate more works.[8][9] The same year, he commissioned Warhol to do a series of paintings after Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper. The works premiered in Milan just months before both men's deaths.[10]

From 1985 until his death in 1987, Iolas was treated with mistrust and malice from a large portion of the Greek press that created a vulgar image of him. He was even accused of illicit trade in antiquities, a case that did not reach the courts because of his death, while all other accusations were dropped as groundless. On the initiative of Costas Gavras, there has been, from abroad, an attempt to defend Iolas, which was co-signed by many internationally recognized personalities, such as the Byzantinologist Helene Glykatzi-Ahrweiler.

Personal life and legacy

[edit]Iolas died from AIDS-related complications at New York Hospital on June 8, 1987. A memorial service was held on September 17, 1987, at the Archdiocesan Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, New York.[11]

Iolas's long-term partner, André Mourgues, said: "Iolas was someone completely positive, he loved everything, and he loved everyone, within reason, he was so positive in his love of life. But, above all else, his real religion was art."[2] Following Iolas's death, Mourgues lived with the remainder of his collection in Paris.[2] The Villa Iolas in Athens, a marble palace that Iolas had built and which he hoped would become a museum, was looted and fell into ruins after his death, the Greek government never acting upon his wishes.[12]

External links

[edit]- Silkscreen print of a Roman-era bronze head of Alexander the Great commissioned to Warhol by Iolas, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Portrait of Alexander Iolas by René Magritte, donated by Iolas to the Centre Pompidou.

- Alexander Iolas collection donated to the Centre Pompidou.

References

[edit]- ^ Christian House, 'Grow Forever, Grow Eternal: A Profile of Alexander Iolas, 12 May 2017, Sothebys.com [1]

- ^ a b c Adrian Dannatt, On How Alexander Iolas And André Mourges (Practically) Invented The Contemporary Art World, 11 March 2022, Sothebys.com [2] Archived 2023-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Coutsoudis-Iolas, Eleni (2021). My Uncle Alexander Iolas: The Man Behind the Myth (in Greek). Athens: Publications Minoas S.A. pp. 34, Iolas's father, Andreas, was involved in the cotton trade in Egypt. He was a classificateur (classifier) and often travelled to Upper Egypt in order to check the quality of cotton. ISBN 978-618-02-1854-1.

- ^ Coutsoudis-Iolas, Eleni (2021). My Uncle Alexander Iolas: The Man Behind the Myth (in Greek). Athens: Publications Minoas S.A. p. 125. ISBN 978-618-02-1854-1.

- ^ Coutsoudis-Iolas, Eleni (2021). My Uncle Alexander Iolas: The Man Behind the Myth (in Greek). Athens: Publications Minoas S.A. p. 144. ISBN 978-618-02-1854-1.

- ^ René, Magritte. "The Healer (Le Therapeute)". National Gallery. Retrieved 2024-03-25.

- ^ Nygard, Travis; Tomasso, Vincent (2015-07-23). "Andy Warhol'sAlexander the Great: an ancient portrait for Alexander Iolas in a postmodern frame". Classical Receptions Journal. 8 (2): 253–275. doi:10.1093/crj/clv005. ISSN 1759-5134.

- ^ Καραμπάσης, Βασίλης (2018-10-08). ""Αλέξανδρος Ιόλας: Η κληρονομιά" στο Μακεδονικό Μουσείο Σύγχρονης Τέχνης". ertnews.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 2023-12-06.

- ^ "Αλέξανδρος Ιόλας: Η Κληρονομία". www.momus.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 2023-12-06.

- ^ "The Man Who Discovered Warhol". 9 August 2017.

- ^ Russell, John (June 12, 1987). "Alexander Iolas, Ex-Dancer And Surrealist-Art Champion". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ Philip Chrysopoulos, 'Alexandros Iolas: The Rise and Tragic Fall of Greece's Greatest Art Collector', 31 March 2022 [3]

- 1908 births

- 1987 deaths

- People from Alexandria

- American art dealers

- Greek art dealers

- American art collectors

- Greek art collectors

- Egyptian people of Greek descent

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- Egyptian expatriates in Germany

- Egyptian expatriates in France

- Egyptian emigrants to the United States

- AIDS-related deaths in New York (state)