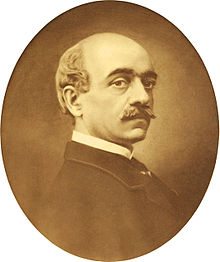

Vasile Alecsandri

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

Vasile Alecsandri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 July 1821 |

| Died | 22 August 1890 (aged 69) |

| Occupation(s) | Poet, playwright, politician, and diplomat |

| Signature | |

| |

Vasile Alecsandri (Romanian pronunciation: [vaˈsile aleksanˈdri]; 21 July 1821 – 22 August 1890) was a Romanian patriot,[1][2][3] poet, dramatist, politician and diplomat.[4] He was one of the key figures during the 1848 revolutions in Moldavia and Wallachia. He fought for the unification of the Romanian Principalities, writing "Hora Unirii" in 1856 and giving up his candidacy for the title of prince of Moldavia, in favor of Alexandru Ioan Cuza. He became the first minister of foreign affairs of Romania and was one of the founding members of the Romanian Academy. Alecsandri was a prolific writer, contributing to Romanian literature with poetry, prose, several plays, and collections of Romanian folklore, being considered, alongside Mihai Eminescu, which admired and was inspired by the writings of Alecsandri, as one of the most important Romanian writers in the second half of the 19th century.

Early life

[edit]Origins and childhood

[edit]Alecsandri was born in the Moldavian town of Bacău and he was of Greek origin. His parents were Vasile Alecsandri, a middle-ranking nobleman,[5] from the noble Greek family of Alecsandri,[6] and Elena Cozoni, a Romanianized Greek woman.[5] They had seven children, of which three survived: one daughter, Catinca, and two sons, Iancu — a future army colonel – and Vasile.

The family prospered in the lucrative business of salt and cereals trade. In 1828, they purchased a large estate in Mircești, a village near Siret River. The young Vasile spent time there studying with a devout monk from Maramureș, Gherman Vida, and playing with Vasile Porojan, a Gypsy boy who became a dear friend. Both characters would later appear in his work.

Adolescence and youth

[edit]Between 1828 and 1834, he studied at the Victor Cuenim "pensionnat", an elite boarding school for boys in Iași. He moved to Paris in 1834, where he dabbled in chemistry, medicine, and law, but soon abandoned all in favor of what he called his "lifelong passion", literature. He penned his first literary essays in 1838 in French, which he had mastered to perfection during his stay in Paris. After a brief return home, he left for Western Europe again, visiting Italy, Spain, and southern France.

Romantic interest

[edit]A year later, Alecsandri attended a party celebrating the name day of Costache Negri, a family friend. He there fell in love with Negri's sister. The 21-year-old and not long divorced Elena Negri responded enthusiastically to the 24-year-old youngster's love declarations. Alecsandri began writing love poems until a sudden illness forced Elena to head abroad to Venice. He met her there, where they shared two torrid months.

They cruised to Austria, Germany, and to Alecsandri's former romping grounds, France. Elena's chest illness aggravated in Paris, and after a brief stint in Italy, they both boarded a French ship to return home 25 April 1847. Tragedy struck on the ship, when Elena died in her lover's arms. Alecsandri channeled his mourning into a poem, "Steluța" (Little Star). Later, he dedicated his "Lăcrimioare" (Little Tears) collection of poems to her.

Midlife

[edit]Political involvement

[edit]In 1848, he became one of the leaders of the revolutionary movement based in Iași. He wrote a widely read poem urging the public to join the cause, "Către Români" (To Romanians), later renamed "Deșteptarea României" (Romania's Awakening). Together with Mihail Kogălniceanu and Costache Negri, he wrote a manifesto of the revolutionary movement in Moldavia, "Dorințele partidei naționale din Moldova" (Wishes of the National Party of Moldavia).

However, as revolution failed, he fled Moldavia through Transylvania and Austria, moving on to Paris, where he continued to write political poems.

Literary achievements

[edit]

After two years, he returned to a triumphant staging of his new comedy, "Chirița în Iași". He toured the Moldavian countryside, collecting, reworking, and arranging a vast array of Romanian folklore, which he published in two installments, in 1852 and 1853. The poems included in these two enormously popular collections became the cornerstone of the emerging Romanian identity, especially the ballads "Miorița", "Toma Alimoș", "Mânăstirea Argeșului", and "Novac și Corbul." His volume of original poetry, "Doine și Lăcrămioare", further cemented his reputation.

Broadly revered in Romanian cultural circles, he oversaw the establishment of "România Literară", to which writers from both Moldavia and Wallachia contributed. He was one of the most vocal unionists, supporting the union the two Romanian provinces, Moldavia and Wallachia. In 1856, he published in Mihail Kogălniceanu's newspaper, Steaua Dunării, the poem "Hora Unirii", which became the anthem of the unification movement.

New romantic interest

[edit]The end of 1855 saw Alecsandri pursuing a new romantic interest, in spite of promises made to Elena Negri on her deathbed. At age 35, the now renowned poet and public figure fell in love with the young Paulina Lucasievici, the daughter of an innkeeper. The romance moved at a lightning pace: they moved in together to Alecsandri's estate at Mircești and, in 1857, their daughter Maria was born.

Political fulfilment

[edit]Alecsandri found satisfaction in the advancement of those political causes he had long championed. The two Romanian provinces united and he was appointed minister of External Affairs by Alexandru Ioan Cuza. He toured the West, pleading to some of his friends and acquaintances in Paris to acknowledge the newly formed nation and support its emergence in the turbulent Balkan area.[7]

Retreat at Mircești

[edit]The diplomatic tours tired him. In 1860, he settled in Mircești for what would be the rest of his life. He married Paulina more than a decade and a half later, in 1876.

Between 1862 and 1875, Alecsandri wrote 40 lyrical poems, including "Miezul Iernii, "Serile la Mircești, "Iarna," "La Gura Sobei", "Oaspeții Primăverii", and "Malul Siretului." He also dabbled in epic poems, collected in the volume "Legende", and he dedicated a series of poems to the soldiers who participated in the Romanian War of Independence.[citation needed] He also wrote the lyrics of Ștefan Nosievici's march "Drum bun".[8]

In 1879, his "Despot-Vodă" drama received the award of the Romanian Academy. He continued to be a prolific writer, finishing a fantastic comedy, "Sânziana și Pepelea," (1881) and two dramas, "Fântâna Blanduziei" (1883) and "Ovidiu" (1884).

In 1881, he wrote Trăiască Regele (Long Live the King), which became the national anthem of the Kingdom of Romania from 1884 until the abolition of the monarchy in 1947.

Alecsandri was also a member of the Macedo-Romanian Cultural Society.[9]

Long suffering from cancer, Alecsandri died in 1890 at his estate in Mircești.[7]

Politics

[edit]Alecsandri had an important political career. He was one of the supporters of slave emancipation. He was allegedly antisemitic,[citation needed] although, according to some Romanian historians (including Neagu Djuvara), he had distant Jewish roots.[10][11][12][13]

The appearance of the literary stereotype of the "Polish Jew," or Ostjude, in Romanian literature was largely due to Vasile Alecsandri, the most important and most popular writer of the time. The Jew was depicted with sidecurls, and caftan, he used characteristic jargon and was portrayed as having "typical" personality traits — he was an unscrupulous cheat, a profit–hungry usurer, an exploiter and "poisoner" of the peasant.[14]

Further reading

[edit]- G. C. Nicolescu, "Viața lui Vasile Alecsandri" Bucharest, 1975

- Alecsandri, Vasile. Poesii Populare ale Romanilor. 1867.[15]

- Alecsandri, Vasile. Les Doïnas. Poésies Moldaves. 1855.[15]

- Alecsandri, Vasile. Strigoiul (The Vampire) (1897)[16][17][18]

References

[edit]- ^ "VASILE ALECSANDRI – 200 – Vasile Alecsandri, un exemplu de mare patriot | Ştiri locale de ultima ora, stiri video - Ştiri Gorjeanul.ro". 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Pagina de istorie: La 21 iulie 1821 s-a născut marele scriitor și patriot român Vasile Alecsandri". 21 July 2022.

- ^ "Poet al întregii romanităţi - LimbaRomana".

- ^ Zantedeschi, Francesca (2022). "Cântecul Gintei Latine : Vasile Alecsandri, "race" connections and the Latinity of the Romanians (1850s–1870s)". Nations and Nationalism. 28 (3): 909–923. doi:10.1111/nana.12843. ISSN 1354-5078. S2CID 248439574.

- ^ a b Murray, Christopher John (2013). Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850. Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-135-45578-1.

- ^ Pruteanu-Isăcescu, Iulian (2021). "Familia Alecsandri. Figuri feminine (I)". Anuarul Muzeului Naţional al Literaturii Române laşi (in Romanian). XIV (XIV): 47–57. ISSN 2066-7469.

- ^ a b Gaster 1911, p. 538.

- ^ Filimon 2020, p. 38.

- ^ Cândroveanu, Hristu (1985). Iorgoveanu, Kira (ed.). Un veac de poezie aromână (PDF) (in Romanian). Cartea Românească. p. 12.

- ^ "Evreii au amprente bogate în existenţa României". Ziuaveche.ro. 17 February 2013.

- ^ "Aurel Vainer: Evreii au amprente bogate în existenţa României". Agerpres.ro. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "REALITATEA EVREIASCĂ - Nr. 400-401" (PDF). Jewishfed.ro. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ ".־ עזרת סופרים. | המליץ | 10 פברואר 1892 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Jpress.org.il.

- ^ Volovici 1991, p. 10.

- ^ a b Martinengo-Cesaresco, Evelyn Lilian Hazeldine Carrington (26 May 2011). Essays in the Study of Folk-Songs (1886). gutenberg.org.

- ^ "Strigoiul (Vasile Alecsandri)". ro.wikisource.org (in Romanian). Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ Alecsandri, Vasile (1886). "Strigoiul". isfdb.org. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ Tudor, Lucia-Alexandra (22 March 2015). "Children of the night". Romanian Journal of Artistic Creativity. 3 (1): 60–104. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

Sources

[edit]- "Vasile Alecsandri". Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 November 2012.

- Filimon, Rosina Caterina (2020). "Ciprian Porumbescu, creator and protagonist of the Romanian operetta". Artes. Journal of Musicology. 21: 36–55. doi:10.2478/ajm-2020-0003.

- Murray, Christopher John (2004). Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-57958-423-3.

- Volovici, Leon (1991). Nationalist Ideology and Antisemitism: The Case of Romanian Intellectuals in the 1930s. Pergamon Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-08 041024-3.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gaster, Moses (1911). "Alecsandri, Vasile". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 538–539.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Vasile Alecsandri at the Internet Archive

- Works by Vasile Alecsandri at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Vasile Aleksandri. Winter. Translated by Daniel Ioniță (audio).

- 1821 births

- 1890 deaths

- People from Bacău

- Writers from the Principality of Moldavia

- Romanian people of Greek descent

- Romanian people of Jewish descent

- 19th-century Romanian poets

- Romanian male poets

- Romanian nationalists

- Romantic poets

- Neoclassical writers

- Junimists

- Romanian writers in French

- 19th-century Romanian dramatists and playwrights

- Romanian male dramatists and playwrights

- 19th-century Romanian male writers

- Founding members of the Romanian Academy

- Deaths from cancer in Romania

- National anthem writers

- Members of the Macedo-Romanian Cultural Society