James Alcock

James E. Alcock | |

|---|---|

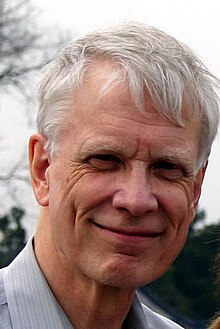

Alcock in 2005 | |

| Born | December 24, 1942 (age 81) |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Alma mater | McGill University BSc (Honours Physics) McMaster University PhD |

| Spouse | Karen Hanley |

| Awards | May 15, 2004 awarded CSICOP's In Praise of Reason Award |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Social Psychology; Psychology of Belief; Psychotherapy |

| Institutions | York University |

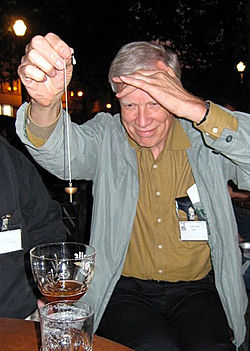

James E. Alcock (born 24 December 1942) is Professor emeritus (Psychology) at York University (Canada).[1] Alcock is a noted critic of parapsychology and a Fellow and Member of the Executive Council for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry.[2] He is a member of the Editorial Board of The Skeptical Inquirer,[3] and a frequent contributor to the magazine. He has also been a columnist for Humanist Perspectives Magazine.[4] In 1999, a panel of skeptics named him among the two dozen most outstanding skeptics of the 20th century.[5] In May 2004, CSICOP awarded Alcock CSI's highest honor, the In Praise of Reason Award.[6] The author of several books and peer reviewed journal articles,[1] Alcock is also an amateur magician and a member of the International Brotherhood of Magicians.[7]

Early life

[edit]Alcock grew up in an observant Protestant household and regularly went to Sunday school. His mother was "very religious" and his father, though not outwardly observant, "never criticized religion". "When I started university, it was difficult, over a period of a couple of years, to give up my belief". As a 19-year-old undergraduate, he attended a stage hypnosis show hosted by Reveen the Impossibilist. He took part in the show as a volunteer and was asked to interlace his hands. He was surprised that at the hypnotist's suggestion he could not separate his hands. "It really freaked me out at the time. It got me really interested in hypnosis. But it's just suggestion."[9]

Education and career

[edit]Alcock has a degree in physics from McGill University. After completion of that degree he was extended admission to the graduate program in physics but instead chose to accept a job at IBM as a Systems Engineer. He then developed an interest in psychology, and subsequently earned a Ph.D. in social psychology from McMaster University. Throughout his career Alcock was a professor of psychology at Glendon College, York University, Toronto, Canada; a clinical psychologist with a private practice; a Fellow of the Canadian Psychological Association; and a member of the American Psychological Association and the Association for Psychological Science. His research concentrated on the psychology of belief, and he participated in a special research project for the National Academy of Sciences regarding the critical evaluation of parapsychology.[10] He was chosen as a fellow of the Canadian Psychological Association for making "a distinguished contribution to the advancement of the science or profession of psychology".[11]

Skepticism and skeptical activism

[edit]James Alcock is a prominent skeptic and a Fellow and Member of the Executive Council for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. His first television appearance was in 1974 when he appeared on the Toronto TVOntario magazine show, The Education of Mike McManus,. He sat on a panel discussing current paranormal research with a parapsychologist and a psychic healer. When asked if he was closed-minded to the possibility of psi, Alcock responded that there is no good research out there that would change his position. "The experiments that have been done... are filled with flaws... they just don't satisfy the canons of science. Until the parapsychologists can present evidence that satisfies the criteria of science there's nothing to investigate, there's no phenomenon there."[12]

In 1976, Alcock attended the organizing conference at which the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal was founded, and was invited to be a Fellow of CSICOP at that time. He was appointed to the Executive Council a few years later.[13]

Alcock's 1981 book, "Parapsychology-Science Or Magic?: A Psychological Perspective," was instrumental in transforming Professor Chris French's skeptical understanding of paranormal events and explaining unusual experiences:

I kind of fell into this trap myself...I used to be a believer, a true believer until quite well into my adulthood. And it was reading one particular book by James Alcock, called 'Parapsychology-Science or Magic?' that made me realize there was another way of explaining all these unusual experiences, and one that actually made a lot of sense to me! ... I can turn 'round to him [James Alcock] and say, 'You are the bastard that got me to where I am today! You've got a lot to answer for![14][15]

A long–time member of the Skeptic's Toolbox faculty, Alcock lectured at the 4-day workshops that taught attendees critical thinking skills for their daily lives. Alcock told a Register-Guard reporter who attended the 2003 conference, "Science has many voices... We encourage people to listen to scientific evidence, but how (in the case of expert testimony in American courts) do we determine who to listen to?" And in the case of printed media, "There are lots of things published that are sheer nonsense." Learning to evaluate evidence is why workshops like the Toolbox are important.[16]

The San Francisco Chronicle asked Alcock to comment on EVP and ghost-hunter instruments. He suggested "several explanations for so-called voices from the dead. One theory is that the recording devices are picking up snatches of radio broadcasts. Another is called 'apophenia,' which means that people tend to perceive patterns even when there are none. If we play the same piece of tape over and over ... we maximize the opportunity for the perceptual apparatus in our brain to 'construct' voices that do not exist."[17]

In October 2004 Alcock spoke at the World Skeptics Congress in Italy.[3] As a member of the executive council of CFI, he addressed the opening session of the 2012 6th World Skeptic Congress in Berlin. He outlined the history of the modern skeptical movement as begun by CSICOP in April 1976 in Buffalo, NY.[18] He has been a featured speaker at CSICon, an annual skeptical conference hosted by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, several times.

Robert Jahn

[edit]Alcock carried out a systematic review of parapsychological research involving random event generators. He found several methodological problems that he considered of such a serious nature that one could not have any confidence in the results and conclusions of the various studies.

Much of the research was carried out in the Princeton University Anomalies Research (PEAR) laboratory of Robert Jahn, then Dean of that university's Engineering faculty. In addition to concerns regarding methodology, Alcock determined that if one were to remove the data related to one particular participant, the results of the study were no longer statistically significant. Moreover, the fact that the participant was the individual who set up and oversaw the research for Dr. Jahn rang alarm bells for James Alcock.[19][20]

Alcock later commented on why he thinks Jahn and other physicists who conduct parapsychological research incorporate methodologically unsound elements into their research: "Here's the problem, physicists don't work with people. They work with subject matter that doesn't lie, that doesn't trick them[...] Physicists often tend to think that they're the true scientists and they probably don't need guidance from anyone else. But the confidence they have in doing the research misguides them when it comes to working with people because when you're dealing with human beings, it's a very different matter. You've got all kinds of subtle influences that can change people's behaviors. You've got all kinds of opportunities for fraud that you wouldn't get when you're studying atoms and molecules."[9]

The Bem experiments

[edit]Media attention was directed toward Daryl Bem's research paper Feeling the Future: Experimental Evidence for Anomalous Retroactive Influences on Cognition and Affect. Alcock responded with his paper Back from the Future: Parapsychology and the Bem Affair by stating, "Bem has reported data suggesting that individuals' future experiences can influence their responses in the present. Careful scrutiny of his report reveals serious flaws in procedure and analysis, rendering this interpretation untenable."[21]

After evaluating Daryl Bem's nine experiments, Alcock claimed to have found metaphorical "dirty test tubes", serious methodological flaws such as changing the procedures partway through the experiments and combining results of tests with different chances of significance. The amount of actual tests done is unknown and no explanation of how it was determined that participants had "settled down" after seeing erotic images was given. Alcock concludes that almost everything that could go wrong with these separate experiments did go wrong. Bem's response to Alcock's critique appeared online at the Skeptical Inquirer website[22] and Alcock replied to these comments in a third article on the same website.[23]

The null hypothesis

[edit]In 2003 Alcock published Give the Null Hypothesis a Chance: Reasons to Remain Doubtful about the Existence of Psi, in which he claimed that parapsychologists never seem to take seriously the possibility that psi does not exist. Because of that, they interpret null results as only that they were unable to observe psi in a particular experiment, rather than accepting null results as indicating the possibility that there is no psi. The failure to take the null hypothesis as a serious alternative to their psi hypotheses leads them to rely upon a number of arbitrary effects to:

- rationalize failures to find predicted effects

- excuse the lack of consistency in outcomes, and

- justify failures to replicate.

"The pursuit of science should be directed at seeking explanations, whatever they are, rather than searching for preferred explanations. Parapsychology is directed at finding evidence that paranormal phenomena exist, rather than at explaining the strange, anomalous experiences that people have from time to time. Parapsychologists show little interest in normal explanations for those experiences because they are committed to finding evidence of the paranormal. Their commitment is such that failures to replicate, rather than suggesting that perhaps there is "nothing there" (the null hypothesis), the failures are reinterpreted in terms of some made-up "effect."[14]

Alcock cites several endemic problems in parapsychological research, including:

- insufficient definition of the subject matter

- total reliance on negative definitions of their phenomena (e.g., psi is said to occur only when all known normal influences are ruled out)

- failure to produce a single phenomenon that can be independently replicated by neutral researchers

- the invention of "effects" such as the psi-experimenter effect to explain away inconsistencies in the data and failures to achieve predicted outcomes

- unfalsifiability of claims

- unpredictability of effects; lack of progress in more than a century of formal research; methodological weaknesses

- reliance on statistical procedures to determine when psi has supposedly occurred, even though statistical analysis does not in itself justify a claim that psi has occurred, and

- failure to jibe with other areas of science.

Overall, he argues that there is nothing in parapsychological research that would lead parapsychologists to conclude that psi does not exist. As such, even if psi does not exist, the search is likely to continue for a long time. To that end, conclusions of parapsychologists like Susan Blackmore who acknowledge lack of psi evidence and abandon the field are "downplayed or ignored". "I continue to believe that parapsychology is, at bottom, motivated by belief in search of data, rather than data in search of explanation."[24]

Belief

[edit]Alcock's book Belief: What it Means to Believe and Why Our Convictions Are So Compelling is a 638 page expansion on his 1995 article "The Belief Engine," where he wrote, "Our brains and nervous systems constitute a belief-generating machine, a system that evolved to assure not truth, logic, and reason, but survival". In the book's foreword, Ray Hyman wrote that the book is an "ideal textbook for a course that provides an integrated overview of all the areas of psychology" and that every "psychologist and psychology student should read it".[25]

Personal life

[edit]Alcock is married to Karen Hanley. His son Erik Alcock is a professional musician/songwriter; two of his songs were included on Eminem's Recovery album, the best-selling album of 2010.[26]

Selected scholarly and professional memberships

[edit]- Member, Joint Designation Committee, Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards/ National Register. 1991- 1997. Chairperson, 1993-95

- Member of Council, Canadian Register of Health Service Providers in Psychology. 1986-1988

- Member, Ontario Board of Examiners in Psychology, 1985-1990. Secretary-Treasurer, 1986-87. Chairperson, 1987-88

- Member, Task Force on Legislation, Ontario Board of Examiners in Psychology 1990-91

- Co-Editor, Special Issue, Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2002

- Member, Editorial Board, Canadian Psychology, 1984-1987.

- Member, Editorial Board, The Skeptical Inquirer.

- Member, Executive Council, Committee for Skeptical Inquiry.

- Series Editor, Psychology Series. Prometheus Books. 1986-89.

- Consulting Editor, The Dictionary of Psychology (R.J. Corsini). Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel. 1999

- Member, Council for Scientific Medicine

- Member, Editorial Board, The Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine

- Member, Commission for Scientific Medicine and Mental Health

- Member, Advisory Board, American Council on Science and Health

Selected publications

[edit]- Alcock, James (1990). Science and Supernature: A Critical Appraisal of Parapsychology. Prometheus Books. ISBN 0879755482.

- Alcock, James (2003). Psi Wars: Getting to Grips with the Paranormal. Imprint Academic. ISBN 0907845487.

- Alcock, James (2005). Parapsychology, Science or Magic?: A Psychological Perspective. Pergamon Press. ISBN 0080257739.

- Alcock, James; D.W. Carment; S.W. Sadava (2005). A Textbook of Social Psychology (6th ed.). Pearson Education Canada. ISBN 0-13-121741-0.

- Alcock, James; Sadava, Stan (2013). An Introduction to Social Psychology: Global Perspectives. SAGE Publications.[27]

- Van der Tempel J. & Alcock J. E. (2015). Relationships between conspiracy mentality, hyperactive agency detection, and schizotypy: supernatural forces at work? Personality and Individual Differences, 82, 136–141. 10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.010.[28]

- Alcock, James (2018). Belief: What it Means to Believe and Why Our Convictions Are So Compelling. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1633884038.[29]

- Reber, A.S. & Alcock, J. (2020). Searching for the impossible: Parapsychology’s elusive quest.[30]

- Alcock, James (2020). Parapsychology: The search science left behind.[31]

- "Electronic Voice Phenomena: Voices of the Dead?"

- "In Praise of Ray Hyman"

- "The Belief Engine"

References

[edit]- ^ a b "York University Faculty Page". 8 April 2016. Archived from the original on 2024-04-14. Retrieved 2024-04-14.

- ^ Frazier, Kendrick; Barry Karr (January–February 2011). "CSI (COP) Renews and Expands Executive Council, Plans for Future Activities". Skeptical Inquirer. 35 (1). Committee for Skeptical Inquiry: 5.

- ^ a b "World Skeptics Congress 2004: James Alcock". CICAP. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ "Index". Humanist Perspectives. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ "Skeptical Inquirer Names the Ten Outstanding Skeptics of the Century" (Press release). Skeptical Inquirer magazine. 14 December 1999. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ Caeddert, John (September–October 2004). "News and Comment". Skeptical Inquirer. 28 (5): 6.

- ^ "Skeptic Toolbox Interviews Pt 1". YouTube. 11 August 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Skeptic's Toolbox Awards – 2". YouTube. 12 August 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ a b "502 Conversations with Dr. James Alcock". YouTube. 502 Conversations. 30 January 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ "James E. Alcock Ph.D." PsychologyToday.com. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ "CPA Fellows". Canadian Psychological Association. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ "The Education of Mike McManus: Psychics & Parapsychology". TVOntario. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ Ray Hyman – Honorary Degree Recipient, Vancouver, BC: Simon Fraser University, October 4, 2007, archived from the original on September 30, 2008, retrieved July 27, 2009

- ^ a b Gerbic, Susan (6 September 2017). "James Alcock – an Interview with Susan Gerbic". Skeptical Inquirer. CSI. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Saunders, Richard. "The Skeptic Zone #292 25 May 2014". The Skeptic Zone. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Baker, Mark (August 17, 2003). "Skeptics gather to sort out normal and paranormal". thefreelibrary.com. The Register Guard. Archived from the original on April 7, 2024. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ Kirby, Carrie (31 October 2005). "Ghost hunters utilize latest in technology; paranormal research has become a popular pursuit". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Skeptical Movement". World Skeptics Congress. 25 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ^ Mccrone, John (26 November 1994). "Psychic powers what are the odds?". New Scientist.

- ^ Alcock, James (1988). A comprehensive review of major empirical studies in parapsychology involving random event generators and remote viewing. In Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, Enhancing human performance: Issues, theories and techniques, Background Papers.. National Academy Press. doi:10.17226/778. ISBN 978-0-309-07810-8. Archived from the original on 2024-04-07. Retrieved 2024-04-07.

- ^ Alcock, James (6 January 2011). "Back from the Future: Parapsychology and the Bem Affair". CSICOP. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ Bem, Daryl (6 January 2011). "Response to Alcock's "Back from the Future: Comments on Bem"". Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Alcock, James (6 January 2011). "Response to Bem's Comments". Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- ^ Alcock, James. "Give the Null Hypothesis a Chance: Reasons to Remain Doubtful about the Existence of Psi" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ Hall, Harriet (2018). "How We Believe". Skeptical Inquirer. 42 (6). Committee for Skeptical Inquirer: 56–59.

The brain can fool us with remarkable experiences that we can't distinguish from external reality, often accompanied by strong emotions and lasting effects.

- ^ "Eminem's 'Recovery' Is 2010's Best-Selling Album; Katy Perry's 'California Gurls' Top Digital Song". Billboard.com. 14 September 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ http://www.sagepub.co.uk/alcocksadava[permanent dead link]. website for the textbook

- ^ Alcock, James; van der Tempel, Jan (2015). "Relationships between conspiracy mentality, hyperactive agency detection, and schizotypy: Supernatural forces at work?". Personality and Individual Differences. 82: 136–141. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.010.

- ^ "New and Notable". Skeptical Inquirer. 42 (3). Committee for Skeptical Inquiry: 60. 2018.

- ^ Reber, Arthur S.; Alcock, James E. (2020). "Searching for the impossible: Parapsychology's elusive quest". American Psychologist. 75 (3): 391–399. doi:10.1037/amp0000486.

- ^ Alcock, James E. (2020). "Parapsychology: The Search Science Left Behind" (PDF). Physics in Canada. 76 (1): 24–28. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-04-14. Retrieved 2024-04-14.