Sino-Albanian split

| Sino-Albanian split | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |

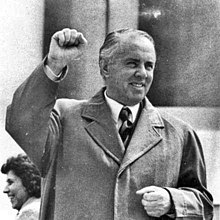

Mao Zedong (left) with Enver Hoxha (right) during a meeting in 1956 | |

| Date | 1972–1978 |

| Location | |

| Caused by | Revisionism, Hoxhaism, Maoism and Imperialism |

| Resulted in | Worsening of Sino-Albanian diplomatic relations, ultimate termination of trade |

| Lead figures | |

The Sino-Albanian split was the gradual worsening of relations between the People's Socialist Republic of Albania and the People's Republic of China in the period 1972–1978.

Both countries had supported each other in the Albanian–Soviet and Chinese–Soviet splits, together declaring the necessity of defending Marxism–Leninism against what they regarded as Soviet revisionism within the international communist movement. By the early 1970s, however, Albanian disagreements with certain aspects of Chinese policy deepened as the visit of Nixon to China along with the Chinese announcement of the "Three Worlds Theory" produced strong apprehension in Albania's leadership under Enver Hoxha. Hoxha saw in these events an emerging Chinese alliance with American imperialism and abandonment of proletarian internationalism. In 1978, China broke off its trade relations with Albania, signalling an end to the informal alliance which existed between the two states.

Origins

[edit]

In September 1956, Enver Hoxha headed a delegation of the Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania (PLA) at the 8th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party. Writing years later of his impressions of the country before the visit, he noted that:

We had followed with sympathy the just war of the fraternal Chinese people against the Japanese fascists and aggressors, Chiang Kai-shek reaction and the American interference... We knew also that at the head of the Communist Party of China was Mao Zedong, about whom personally, as well as about the party which he led, we had no information other than what we heard from the Soviet comrades. Both during this period and after 1949 we had not had the opportunity to read any of the works or writings of Mao Zedong, who was said to be a philosopher and to have written a whole series of works. We welcomed the victory of October 1, 1949, with heartfelt joy and we were among the first countries to recognize the new Chinese state and establish fraternal relations with it. Although greater possibilities and ways were now opened for more frequent and closer contacts and links between our two countries, these links remained at the level of friendly, cultural and commercial relations, the sending of some second-rank delegation, mutual support, according to the occasion, through public speeches and statements, the exchange of telegrams on the occasion of celebrations and anniversaries, and almost nothing more.[1]

Khrushchev's rehabilitation of Josip Broz Tito and the Yugoslavia and his "Secret Speech" denouncing Joseph Stalin in February 1956 put the Soviet leadership at odds with its Albanian counterpart.[2][3] According to the Albanians, the "Khrushchev group's approaches to the Yugoslav revisionists and its open denigration of Joseph Stalin were the first open distortions of an ideological and political character, which were opposed by the PLA."[4] After arriving in Beijing on September 13, Hoxha held his first (and only) meeting with Mao Zedong in between sessions of the party's congress. Mao's first two questions concerned Yugoslav-Albanian ties and the Albanians' opinion on Stalin. Hoxha replied that Albania's relations with Yugoslavia were "cold" and he gave Mao "a brief outline, dwelling on some of the key moments of the anti-Albanian and anti-Marxist activity of the Yugoslav leadership." On the subject of Stalin, Hoxha stated that the Party of Labour considered him "a leader of very great, all-round merits, a loyal disciple of Lenin and continuer of his work." Mao argued that the 1948 Information Bureau decision to expel Yugoslavia was incorrect, and also stressed what he considered to have been Stalin's mistakes in regard to China.[5]

Hoxha later recalled that

"Our impressions from this meeting were not what we had expected... We were especially disappointed over the things we heard from the mouth of Mao about the Information Bureau, Stalin and the Yugoslav question. However, we were even more surprised and worried by the proceedings of the 8th Congress. The whole platform of this Congress was based on the theses of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, indeed, in certain directions, the theses of Khrushchev had been carried further forward... Apart from other things, in the reports which Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping and Zhou Enlai delivered one after the other at the 8th Congress they defended and further deepened the permanent line of the Communist Party of China for extensive collaboration with the bourgeoisie and the kulaks, 'argued' in support of the great blessings which would come to 'socialism' from treating capitalists, merchants, and bourgeois intellectuals well and placing them in high leading positions, vigorously propagated the necessity of collaboration between the working class and the national bourgeoisie, and between the communist party and the other democratic nationalist parties, in the conditions of socialism, etc., etc. In fact, the 'hundred flowers' and the 'hundred schools' of Mao Zedong... constituted the Chinese variant of the bourgeois-revisionist theory and practice about the 'free circulation of ideas and people', about the coexistence of a hotch-potch of ideologies, trends, schools and coteries within socialism."[6]

According to Hoxha, Mao at the 1957 International Conference of the Communist and Workers' Parties declared that, "If Stalin were here, we would find it difficult to speak like this. When I met Stalin, before him I felt like a pupil in front of his teacher, while with Comrade Khrushchev we speak freely like equal comrades" and condemned the "Anti-Party Group" of Molotov and others. Hoxha also claimed that Mao expressed regret that the Yugoslavs refused to attend the conference, with Mao speaking of those "who are 100 per cent Marxists, and others who are 80 per cent, 70 per cent or 50 per cent, indeed there are some who may be only 10 per cent Marxists. We ought to talk even with those who are 10 per cent Marxists, because there are only advantages in this. Why should we not gather, two or three of us, in a small room and talk things over? Why should we not talk, proceeding from the desire for unity?" In Hoxha's view the refusal of the Yugoslavs to attend, as well as both Soviet and Chinese desires to enhance their prestige in the world communist movement in response to events over the previous year, produced a situation where "the 1957 Moscow Declaration [resulting from the Conference], in general, was a good document" owing to its emphasis on opposing revisionism, which both the Soviets and Chinese found advantageous to stress at the time.[7][8]

According to William E. Griffith, the Chinese position on international affairs had begun to shift to the left owing to deepening contradictions with the Soviet Union and the failure of the Hundred Flowers Campaign at home. "Only when the Chinese decided, in 1957 and openly in 1960, to challenge Soviet domination of the [communist] bloc did they seriously look around for allies whom they were ready and willing to support."[9] By 1960 the Albanians found themselves in ideological agreement with the Chinese, as Elez Biberaj notes: "The Chinese had criticized Khrushchev for his rapprochement with Tito, and considered the toleration of Yugoslav 'revisionism' dangerous to the entire communist bloc... Although the seeds of the Sino-Soviet conflict were sown during Stalin's time, policy differences between Beijing and Moscow emerged during the mid- and the late 1950s, coinciding with the deterioration of Albanian-Soviet relations."[10] The Chinese found the Albanians useful owing to their hostility to perceived Soviet revisionism, with Albanian articles on the subject being reprinted in the Chinese media.[11]

In November 1960 the Second International Conference of the Communist and Workers' Parties was to be held, and a Commission was created in October to prepare for it. The Albanian delegation headed by Hysni Kapo and the Chinese delegation headed by Deng Xiaoping, however, were at odds; Kapo's speech to the Commission criticized the Soviet handling of the Bucharest Conference and its attacks on China, whereas Deng stated that, "We are not going to speak about all the issues... We are not going to use such terms as 'opportunist', or 'revisionist', etc." Neither Kapo nor Ramiz Alia (another member of the delegation) felt this stand was correct, with Hoxha sending letters to the delegation calling Deng's speeches "spineless" and further replying that, "They are not for carrying the matter through to the end... They are for mending what can be mended, and time will mend the rest... If I were in the Soviets' shoes, I would accept the field which the Chinese are opening to me, because there I will find good grass and can browse at will." Alia thus wrote that on the subject of principles, "The Chinese were concerned only about the [Soviet] 'conductor's baton', which they wanted to break. They went no further."[12]

Nonetheless, Hoxha recalled years later that, concerning the breakdown in relations between China and the Soviet Union, "we were quite clear that [the Soviets] did not proceed from principled positions in the accusations they were making against the Chinese party. As became even clearer later, the differences were over a series of matters of principle which, at that time, the Chinese seemed to maintain correct stands. Both in the official speeches of the Chinese leaders and in their published articles, especially in the one entitled 'Long Live Leninism', the Chinese party treated the problems in a theoretically correct way and opposed the Khrushchevites."[13] On this basis it defended the activity of the Communist Party of China at the Conference, "it did so in full consciousness in order to defend the principles of Marxism-Leninism, and not to be given some factories and some tractors by China in return."[14]

1960s

[edit]

Griffith wrote in the early 60s that "Albanian documents are notable for their tone of extreme violence and defiance. A remarkable combination of traditional Balkan fury and left-wing Marxist-Leninist fanaticism, the Albanian anti-Khrushchev polemics... were certainly much more extreme than the relatively moderate, flowery, and above all 'correct' language in which the Chinese Communists have normally couched their most icy blasts against Moscow... It seems doubtful that Peking initiated or even necessarily approved the intensity and extent of the Albanian verbal violence... they quite possibly could not or did not feel it wise to restrain him."[15] One author noted that "Hoxha's speech [to the November 1960 Conference] so vehemently denounced Khrushchev that even the Chinese delegates looked embarrassed."[16]

With both states claiming that the Soviet leadership had betrayed Marxism–Leninism and was presiding over the restoration of capitalism in the USSR, "China came to be perceived as having replaced the Soviet Union as the leader of the 'anti-imperialist struggle.' This image was reinforced by the poor state of Beijing's relations with the capitalist countries in general. ... The revolutionary spirit characterizing the Chinese society was highly regarded by the Albanian leadership, and was considered as an indication of the Marxist-Leninist character of the CCP and its policies. During the formative years of the alliance, Tiranë looked to Beijing as a center for the development of a new and 'truly' Marxist-Leninist movement."[17] In 1964 Zhou Enlai visited Albania and signed a joint statement which, among other things, stated that, "Relations between socialist countries, big or small, economically more developed or less developed, must be based on the principles of complete equality... It is absolutely impermissible to impose the will of one country upon another, or to impair the independence, sovereignty and interests of the people, of a fraternal country on the pretext of 'aid' or 'international division of labor.'"[18]

The informal alliance between China and Albania was considered by Jon Halliday to be "one of the oddest phenomena of modern times: here were two states of vastly differing size, thousands of miles apart, with almost no cultural ties or knowledge of each other's society, drawn together by a common hostility to the Soviet Union."[19] Biberaj wrote that it was unusual, "a political rather than a military alliance" without any formal treaty having been signed and "lacking an organizational structure for regular consultations and policy coordination," being "characterized by an informal relationship conducted on an ad hoc basis."[20]

One early disagreement between the Chinese and Albanians concerned the character of the Soviet leadership and polemics against it. In July 1963 Hoxha wrote in his diary that, "The Chinese are saying about Khrushchev today what Khrushchev said about Tito yesterday: 'He is an enemy, a Trojan horse, but we must not let him go over to the enemy, must not let him capitulate, because there is the question of the peoples of Yugoslavia', etc." and that "we are not dealing with a person or a group that is making some mistakes, that in the middle of the road sees the disaster looming up ahead and turns back; in this case it would be essential to manoeuvre, without giving way on principles, 'to prevent him from going over to the imperialists'. But with Khrushchev it is not at all in order, or correct, even to consider, let alone do such a thing. He has betrayed completely."[21] The Chinese were reluctant to engage in public polemics with the Soviet leadership in 1961–63, stressing the need for a "united front" against the Americans and accordingly asking the Albanians to tone down their own polemics and ask for the restoration of diplomatic relations from the Soviet Union, with the Albanians taking offense to such views.[22]

Another early disagreement between the Chinese and Albanians was over the subject of border disputes. Hoxha wrote in his diary in August 1964 that "Chou En-lai raises with the Rumanians territorial claims against the Soviet Union. He accuses the Soviet Union (Lenin and Stalin because, this 'robbery', according to Chou En-lai, took place in their time) of having seized Chinese, Japanese, Polish, German, Czech, Rumanian, Finnish, and other territories. On the other hand, Chou En-lai tells the Rumanians that they are doing well to claim the territories which the Soviet Union has seized from them. These are not Marxist-Leninist, but national-chauvinist positions. Regardless of whether or not mistakes may have been made, to raise these things now, when we are faced, first of all, with the ideological struggle against modern revisionism, means not to fight Khrushchev, but on the contrary to assist him on his chauvinist course."[23] In September that year the Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania sent a letter to the CC of the CCP on the Sino-Soviet border dispute, stating that, "Under the pressure of Khrushchev's revisionist propaganda, under the influence of Khrushchev's slanders and calumnies, and for many other reasons, the masses of the Soviet people will not understand why People's China is now putting forth territorial claims to the Soviet Union, they will not accept this, and Soviet propaganda is working to make them revolt against you. But we think that even true Soviet communists will not understand it, nor will they accept it. This would be a colossal loss for our struggle." The CC of the CCP did not reply.[24]

With the downfall of Khrushchev and rise of Leonid Brezhnev in October 1964 the Chinese called for the Party of Labour of Albania to join in supporting the new leadership "in the struggle against the common enemy, imperialism."[25] The Party of Labour felt that Brezhnev's rise merely represented "Khrushchevism without Khrushchev" and in a letter to the CC of the CCP urged the continuation of polemics against the Soviet leadership, whereas the Chinese sought to get the Albanians to send a delegation to Moscow together with their own delegation headed by Zhou Enlai.[26] Recalling this incident in 1968 Hoxha wrote that, "Chou En-lai went to Moscow without us and there he suffered [an] ignominious defeat... Later we were told: 'We made a mistake in going to Moscow and in proposing it to you, too', etc., etc."[27] Regardless of these and future differences between the two informal allies, the Albanians subsequently wrote that they "supported China publicly... in the international arena for those stands of the Chinese side which were correct."[28]

A constant irritant on the Albanian side was an inability to have regular contacts with the Chinese. Examining Hoxha's two-volume Reflections on China (consisting of extracts from his political diary), Halliday writes that,

"If there is a central theme to the whole 1600 pages, it is the problem of deciphering China's actions... In the very first entry... Hoxha writes that in spite of the importance of consulting about 'revisionism', 'up to now, the Chinese have not had any contact at all with us to discuss these things. Were our enemies to know that between us there is no consultation at all about the fight against the modern revisionists, they would be astonished. They would never believe it. But that is how things stand.' ... Hoxha presents the decade and a half of 'alliance' with China as years when Albania had to muzzle itself quite a lot, with the occasional bust-out to signal disapproval of China's actions... The diary is rich in accounts of his attempts to decode both published statements and acts, on the one hand, and (something not so widely known) the private communications of the Chinese to the Albanians which were also in 'code'. In the end, Hoxha is reduced to watching the TV of his hated Yugoslavia and capitalist Italy."[29]

In October 1966 Hoxha delivered a speech to a plenum of the CC of the Party of Labour titled "Some Preliminary Ideas about the Chinese Proletarian Cultural Revolution," noting that, "We have been informed about and have followed the recent developments in China only through the Chinese press and Hsinhua. The Communist Party of China and its Central Committee have not given our Party and its Central Committee any special comradely information. We think that as a party so closely linked with ours, it ought to have kept us better informed in an internationalist way, especially during these recent months." Hoxha analyzed the events in China in an overall negative fashion, criticizing among other things the fact that the CCP had not held a congress in ten years and that four years had gone by without a plenum of the CC being called, a practice which "cannot be found in any Marxist-Leninist party." Hoxha said that "the cult of Mao was raised to the skies in a sickening and artificial manner" and further added that, in reading of its purported objectives, "you have the impression that everything old in Chinese and world culture should be rejected without discrimination and a new culture, the culture they call proletarian, should be created." He further stated that, "It is difficult for us to call this revolution, as the 'Red Guards' are carrying it out, a Proletarian Cultural Revolution... the enemies could and should be captured by the organs of the dictatorship on the basis of the law, and if the enemies have wormed their way into the party committees, let them be purged through party channels. Or in the final analysis, arm the working class and attack the committees, but not with children."[30]

The beginning of the Cultural Revolution coincided with the intensification of the Albanian Ideological and Cultural Revolution in the fields of culture, economics and politics, which unlike its Chinese counterpart was presented as "a continuation and deepening of policies, programs, and efforts undertaken by Albania over a period of some twenty years," with other differences being that Hoxha's presence was never given "the symbolic and mystical stature in the Albanian revolution that Mao Tse-tung enjoyed in China," there was no inner-party factional struggle at the root of Albanian initiative, the Albanian army played no significant role in events, and there were no Albanian equivalents to the Red Guards nor was there an "influx of supporters of the revolution from the provinces to Tiranë... no public purges, no turmoil in the State University of Tiranë or dislocations of the school system, and no damaging blow to the economy as a result of changes brought on by the revolution."[31] The Albanians also resisted Chinese efforts to get them to praise "Mao Zedong Thought" as constituting a "higher stage" of Marxism–Leninism.[32]

Another difference between the Albanians and Chinese was on the treatment of "anti-revisionist" parties in Europe and elsewhere who openly upheld the positions of the Albanians and Chinese against the Soviet Union, with the Chinese being reluctant to organize them in joint endeavors due to fears of alienating "neutral" parties such as those in North Korea and North Vietnam, whereas the Albanians took an active interest in such efforts; Hoxha wrote that the CCP:[33][34]

"is avoiding general meetings... It holds meetings with other parties, one at a time, which it is entitled to do, and after such meetings these parties come out with statements and articles which defend everything which China says and does. Now the entire concern of the Communist Party of China is that the Marxist-Leninist communist movement should accept that the ideas of Mao Tsetung lead the world, accept the cult of Mao, the Proletarian Cultural Revolution and the entire line of the Communist Party of China with its good points and its mistakes... Just as the opinions of one party cannot be accepted en bloc, neither can those of two parties be accepted en bloc. All must state their opinion. Therefore, the joint meeting and the taking of joint decisions is important."

Following the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 an Albanian delegation to Beijing was told by Zhou Enlai that "Albania, as a small country, had no need of heavy armament and that it was not at all in a position to defend itself alone from foreign aggression... Therefore, according to Chou En-lai, the only road for Albania to cope with foreign aggression was that of... concluding a military alliance with Yugoslavia and with Rumania... [and he] repeated this same thesis to the Albanian Government delegation which had gone to Peking in July 1975... [which] was turned down again by our delegation in a clear-cut and categorical manner."[35] An indication of the Albanian position on Romania was shown by Nicolae Ceaușescu's visit to China in June 1971, with Hoxha writing in his diary that: "Hsinhua reported only that [Mao] said to him: 'Rumanian comrades, we should unite to bring down imperialism'. As if Ceausescu and company are to bring down imperialism!! If the world waits for the Ceausescus to do such a thing, imperialism will live for tens of thousands of years. It is the proletariat and the peoples that fight imperialism."[36]

1970s

[edit]Following Lin Biao's downfall the Chinese leadership began seeking an accommodation with the United States against the Soviet Union, viewing the latter as a more dangerous opponent to its interests.[37] Henry Kissinger's visit to China in July 1971 and the subsequent announcement of Nixon's visit came as a shock to the Albanians, with Hoxha writing in his diary at the time that "when the Americans were killing and bombing in Vietnam and the whole of Indochina, China held secret talks with the Americans... These disgraceful, anti-Marxist, uncomradely negotiations were held without the knowledge of the Vietnamese, let alone any knowledge on our part. This was scandalous. This was a betrayal of the Chinese towards the Vietnamese, towards their war, towards us, their allies, and all the other progressive peoples. This is revolting."[38][39]

A month later the CC of the Party of Labour of Albania sent a letter to its Chinese counterpart strongly protesting the decision to receive Nixon, writing among other things that

"regardless of the result of the talks, the very fact that Nixon, who is known as a rabid anti-communist, as an aggressor and murderer of peoples, as the representative of the blackest of American reaction, is to be received in China, has many minuses and will bring many negative consequences to the revolutionary movement and our cause. There is no way in which Nixon's visit to China and the talks with him can fail to create harmful illusions about American imperialism. ... It will exert a negative influence on the resistance and struggle of the American people themselves against the policy and aggressive activity of the government of Nixon, who will seize the opportunity to run for President again. ... It is not hard to guess what the Italian workers who clashed with the police and demonstrated their repugnance to Nixon's recent visit to Italy, the Japanese workers who did not allow Eisenhower even to set foot on their territory, and the peoples of Latin America who protested and rose against the Rockefellers and all the other envoys of the Washington government, will think. Only the Yugoslav Titoites and the Rumanian revisionists welcomed President Nixon to their capitals with flowers."

The CC of the CCP did not reply to the letter.[40][41] In that year and in 1972, however, the Chinese did send messages notifying the Albanians that they should expect a lower level of economic activity with China in the future.[42]

In October 1971 Hoxha was informed that the Chinese would not be sending a delegation to the 6th Congress of the Party of Labour held next month, which prompted Hoxha to write that, "Every cloud has a silver lining. Reaction and the revisionists will make the most of this anti-Marxist action of the leadership of the Communist Party of China, but the international communist movement will judge how right our Party has been in its line and how wrong the Communist Party of China is on this question."[43] At the 6th Congress Hoxha indirectly criticized recent Chinese foreign policy moves by declaring that, "As long as American imperialism and the Soviet revisionist imperialism are two imperialist superpowers and come out with a common counter-revolutionary strategy, it is impossible for the struggle of the peoples against them not to merge into a single current. You cannot rely on the one imperialism to oppose the other."[44][45]

In 1973 China's trade with Albania experienced a significant decline, to $136 million from $167 million a year earlier.[46] Reflecting on China's relations with the Party of Labour at this point, Hoxha wrote that "Chou En-lai, Li Hsien-nien and Mao have cut off their contacts with us, and the contacts which they maintain are merely formal diplomatic ones. Albania is no longer the 'faithful, special friend'. For them it comes at the end of the line, after Rumania and Yugoslavia in Europe ... it is quite obvious that their 'initial ardour' has died."[47][48][49] In April the same year Geng Biao informed the Albanians that "China does not approve the creation of Marxist-Leninist parties and does not want the representatives of these parties to come to China. Their coming is a nuisance to us but we can do nothing about them, for we cannot send them away. We accept them just as we accept the representatives of bourgeois parties."[50]

In 1974–75 various figures in Albanian military, economic and cultural fields were arrested, with some executed on charges of plotting a coup d'état which would install a government favorable to greater ties with the West and which would promote economic and cultural liberalization on broadly Yugoslav lines.[51][52] In his diary at the time Hoxha wrote that,

"The Chinese make a friend of any state, any person, whether Trotskyite, Titoite, or a Chiang Kai-shek man, if he says, 'I am against the Soviets'. We are opposed to this principle... It is clear that the Chinese do not like these and other stands of ours, because they tear down the Marxist-Leninist disguise they want to maintain, therefore they are exerting pressure on us. This pressure is economic, because politically and ideologically they have never made us yield and will never be able to make us yield. ... Their pressure is not imaginary, but took concrete form in the military and economic plot headed by Beqir Balluku, Petrit Dume, Hito Çako, Abdyl Këllezi, Koço Theodhosi, Lipe Nashi, etc." [53]

In April 1974 Deng Xiaoping, head of the Chinese delegation to the United Nations, proclaimed the "Three Worlds Theory" at a speech to its General Assembly, which declared that the world was divided into "first" (the United States and the Soviet Union), "second" (France, Great Britain, West Germany, Japan, etc.), and "third" (the various countries of Africa, Latin America and Asia) worlds, of which China was declared to be in the third.[54] Writing on such matters, Hoxha declared that, "When China took its pro-American and anti-Soviet stance, this policy was manifested in all its relations with the foreign world. Imperialist America, the fascists Pinochet and Franco, Tito and Ceausescu, renegades and adventurers, German revanchists and Italian fascists are its friends. For China ideology has no importance... The Chinese imagine (there is no other way their actions can be interpreted) that the whole world thinks and is convinced that China is red and revolutionary. This policy which China is pursuing has a 'revolutionary' aim: to unite the 'third world', the 'second world' and American imperialism against the Soviet social-imperialists. And from their actions it turns out that in order to achieve this 'ideal' they must not take much account of principles. 'We now defend the United States of America,' the Chinese justify themselves, 'because it is weaker than the Soviet Union, but with this we must also deepen the contradictions between the Soviet Union and the United States of America'. ... Having deviated from a principled Marxist-Leninist class policy, China, naturally, must base itself on the political conjunctures, on the manoeuvres and intrigues of reactionary governments."[55]

In response to Albania's refusal to endorse the "Three Worlds Theory," the rapprochement with the United States, and other activities, "Beijing had drastically reduced the flow of its economic and military assistance" to Albania by 1976, trade declining to $116 million in that year from $168 in 1975.[56]

Culmination

[edit]

At the 7th Congress of the Party of Labour, held in November 1976, Hoxha indicated his opposition to the new Chinese leadership that had taken over with the death of Mao Zedong in September by refusing to mention Hua Guofeng and openly denouncing Deng Xiaoping while calling for a multilateral meeting of Marxist–Leninist parties.[57] According to the Albanians in their 1978 letter to the Chinese, the latter had tried to pressure them to denounce those who were not part of the ruling group in China: "As we did not do this, it comes to the conclusion that we are partisans of Lin Piao and 'the gang of four'. It is wrong in both aspects. ... The Party of Labour of Albania never tramples on Marxist-Leninist principles, and has never been, nor will it ever be, anybody's tool."[24] The Congress also saw activity on the part of various delegations from "anti-revisionist" parties, 29 in all, of whom a number expressed definite preference for the Albanian line over its Chinese counterpart.[58][59]

Speaking at the Congress, Hoxha reiterated his declaration at the 6th Congress on opposing both superpowers equally, and also denounced the Common Market and NATO, both of which were looked upon favorably by China in its anti-Soviet strategy. "Loyal to the interests of the revolution, socialism, and the peoples," Hoxha said, "our Party will support the proletariat and the peoples who are against the two superpowers and for their destruction, against the capitalist and revisionist bourgeoisie and for its overthrow."[60] In December the Albanians were given a Chinese note criticizing Hoxha's report to the Congress, with Hoxha deciding to have the CC of the Party of Labour give an official reply, stressing in it that "the PLA is an independent Marxist-Leninist party which formulates its own line itself, from the viewpoint of the Marxist-Leninist theory, on the basis of realistic analyses of the internal and external situation... it accepts criticism by sister Marxist-Leninist parties, and it will discuss many problems with them, and vice-versa, the PLA also has the same right towards other sister parties." Hoxha also had the reply mention that various letters sent to the CC of the CCP by its Albanian counterpart never received replies, such as the letter on Nixon's decision to visit China. The new Albanian letter did not receive a reply.[61]

Around this time Hoxha began analyzing the works of Mao Zedong and the history of the Communist Party of China. As part of his examination of the then-recently released 1956 Mao speech "On the Ten Major Relationships" in late December, Hoxha wrote of the Sino-Soviet split that

"Mao's aim was to help not Khrushchev but himself, so that China would become the main leader of the communist world... He wanted meetings, wanted social-democratic agreements because he himself was a social-democrat, an opportunist, a revisionist. But Mao could not extinguish the fire [against perceived Soviet revisionism] or the polemic, and seeing that he was unable to establish his hegemony, he changed his stand. Mao took a somewhat 'better' anti-Soviet stand, and here he appeared to be in accord with us who were fighting Khrushchevite revisionism consistently. But even at this time he had hopes of rapprochement with the Khrushchevite revisionists. ... Then, from the strategy of the fight on the two flanks he turned towards the United States of America."

Hoxha further wrote that: "Mao Tsetung accuses Stalin of left adventurism, of having exerted great pressure on China and the Communist Party of China. ... Glancing over all the main principles of Mao Tsetung's revisionist line, in regard to all those things which he raises against Stalin, we can say without reservation that Stalin was truly a great Marxist-Leninist who foresaw correctly where China was going, who long ago realized what the views of Mao Tsetung were, and saw that, in many directions, they were Titoite revisionist views, both on international policy and on internal policy, on the class struggle, on the dictatorship of the proletariat, on peaceful coexistence between countries with different social systems, etc."[62]

In May 1977 a Chinese parliamentary delegation visited Romania and Yugoslavia, but not Albania, and referred to the Yugoslav system as socialist while praising the Non-Aligned Movement, while Tito was invited to Beijing in August and praised by his hosts.[63][64] In September 1978 Tito declared that, according to Hua, "Mao Zedong said that he should have invited me for a visit, stressing that in 1948, too, Yugoslavia was in the right, a thing which he had declared even then, to a narrow circle. But, taking into consideration the relations between China and the Soviet Union at that time, this was not said publicly."[65]

On July 7, 1977, an editorial in Zëri i Popullit written but not signed by Hoxha and entitled "The Theory and Practice of the Revolution" openly attacked the "Three Worlds Theory" by name and thus signified a direct attack on the Chinese.[66][67][68] Among other things the editorial stated that,

"The Marxist-Leninists do not confuse the fervent liberation, revolutionary and socialist aspirations and desires of the peoples and the proletariat of the countries of the so-called 'third world' with the aims and policy of the oppressive compradore bourgeoisie of those countries ... to speak in general terms about the so-called 'third world' as the main force of the struggle against imperialism ... means a flagrant departure from the teachings of Marxism-Leninism and to preach typically opportunist views ... according to the theory of the 'three worlds', the peoples of those countries must not fight, for instance, against the bloody fascist dictatorships of Geisel in Brazil and Pinochet in Chile, Suharto in Indonesia, the Shah of Iran or the King of Jordan, etc., because they, allegedly, are part of the 'revolutionary motive force which is driving the wheel of world history forward'. On the contrary, according to this theory, the peoples and revolutionaries ought to unite with the reactionary forces and regimes of the 'third world' and support them, in other words, give up the revolution...

The supporters of the theory of 'three worlds' claim that it gives great possibilities for exploitation of inter-imperialist contradictions. The contradictions in the enemy camp should be exploited, but in what way and for what aim? ... The absolutisation of inter-imperialist contradictions and the underestimation of the basic contradiction, that between the revolution and the counter-revolution ... are in total opposition to the teachings of Marxism-Leninism...

This is an anti-revolutionary 'theory' because it preaches social peace, collaboration with the bourgeoisie, hence giving up the revolution, to the proletariat of Europe, Japan, Canada, etc. ... it justifies and supports the neo-colonialist and exploiting policy of the imperialist powers of the 'second world' and calls on the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America not to oppose this policy, allegedly for the sake of the struggle against the superpowers."[69]

Hoxha wrote on the occasion of the editorial's publication that,

"The Chinese did not make the slightest effort to defend their notorious theses about the revolution, because in fact there was no way in which they could defend them, because the division into three worlds and the inclusion of China in the 'third world', is nothing but an effort to extinguish the proletarian revolution and make the proletariat submit to the yoke of the capitalist bourgeoisie of the industrialized countries and of American imperialism. This absurd anti-Marxist theory allegedly combated Soviet social-imperialism which was endangering American imperialism, Chinese social-imperialism and the developed capitalist countries. The Chinese theories, which have their source in the bourgeois-revisionist views of Mao Tsetung, Chou En-lai, Teng Hsiao-ping and Chairman Hua, take no account at all of the peoples and the revolution." [70]

The Chinese temporarily revived their interest in the pro-Chinese parties in order to use them as polemicists against attacks on the "Three Worlds Theory" while pro-Albanian parties fought back; on November 1 People's Daily dedicated its entire issue that day to an article entitled "Chairman Mao's Theory of the Differentiation of the Three Worlds Is A Major Contribution to Marxism-Leninism" in recognition that China could no longer rely entirely on proxies in defending its foreign policy from the Albanians.[71]

In December 1977 Hoxha recorded in his diary that a group of Chinese specialists were not being sent to Albania because in their excuse "the appropriate conditions do not exist, therefore as long as good conditions and understanding have not been created, we are not going to send our specialists for these objects."[72] In April and May 1978 the Albanian Foreign Ministry made an official complaint that Chinese experts in the country "had the deliberate intention of harming Albania's economy" and on July 7 that year, on the first anniversary of the publication of "The Theory and Practice of the Revolution," the Chinese Foreign Ministry informed the Albanian embassy in Beijing that it was ceasing all economic and military agreements with the country.[73] On July 29 the Albanians replied, declaring the July 7 decision

"a reactionary act from great power positions, an act which is a repetition, in content and form, of the savage and chauvinist methods of Tito, Khrushchev and Brezhnev which China, also, once condemned. The Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania and the Albanian Government reject the attempts made in the Chinese note to blame Albania, to groundlessly accuse the Albanian leadership of allegedly being ungrateful for China's aid and of allegedly having tried to sabotage the economic and military cooperation between the two countries. To any normal person it is unbelievable and preposterous that Albania, a small country, which is fighting against the imperialist-revisionist encirclement and blockade and which has set to large-scale and all-round work for the rapid economic and cultural development of its country, which is working tirelessly for the strengthening of the defence capacity of its socialist Homeland, should cause and seek cessation of economic cooperation with China, refuse its civil and military loans and aid." [74]

The letter went on to note delays on the Chinese side in providing equipment and materials for the vast majority of its economic projects in Albania, but also concluded that, "The true motives for the cessation of aid and loans to Albania have not an exclusively technical character, as the note of the Chinese Government makes out, on the contrary they have a deep political and ideological character."[75][76] The letter concluded that, "Albania will never submit to anybody, it will stand to the end loyal to Marxism-Leninism and proletarian internationalism. It will march non-stop on the road of socialism and communism illuminated by the immortal teachings of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin. ... Though encircled, socialist Albania is not isolated because it enjoys the respect and love of the world proletariat, the freedom-loving peoples and the honest men and women throughout the world. This respect and love will grow even more in the future. Our cause is just! Socialist Albania will triumph!"[77]

Subsequent developments

[edit]Following the split with China, the Albanians proclaimed that their country was the only one in the world genuinely constructing a socialist society.[78] In December 1977 Hoxha wrote an analysis of the Chinese revolution, declaring that, contrary to the Chinese view, "in general, the decisions and directives of the Comintern, first of all of the time of Lenin, were correct, and that those of the time of Stalin were correct, too." On the character of the revolution he wrote that, "In my opinion, and as far as I can judge, China carried out a bourgeois-democratic revolution of a new type through the national liberation armed struggle" and that "the revolution in China could not be carried through to the end. ... So long as the working class in China shared power with the bourgeoisie, this power, in essence, was never transformed into a dictatorship of the proletariat, and consequently the Chinese revolution could not be a socialist revolution."[79]

Biberaj writes that throughout the alliance the Albanians had a definite advantage in that "the scope of China's decision-making participation in Albania was insignificant ... it was the Albanians rather than the Chinese who decided on the use of the aid... Tiranë was in a stronger bargaining position than Beijing because the Chinese were more keen in maintaining the alliance."[80] Peter R. Prifti noted that Albania's relations with China "emphasize[d] once again the great importance the Albanian leaders attach to ideology ... [and] proved conclusively—if such proof were needed—Albania's independence of China. It demonstrated that the Albanian Party was not a mere mouthpiece of Peking but follows a basically independent foreign policy."[81]

Recalling his pre-1956 impressions of China, Hoxha once wrote that,

"It was said that Mao was following an 'interesting' line for the construction of socialism in China, collaborating with the local bourgeoisie and other parties, which they described as 'democratic', 'of the industrialists', etc., that joint private-state enterprises were permitted and stimulated by the communist party there, that elements of the wealthy classes were encouraged and rewarded, and even placed in the leadership of enterprises and provinces, etc., etc. All these things were quite incomprehensible to us and however much you racked your brains, you could not find any argument to describe them as in conformity with Marxism-Leninism. Nevertheless, we thought, China was a very big country, with a population of hundreds of millions, it had just emerged from the dark, feudal-bourgeois past, had many problems and difficulties, and in time it would correct those things which were not in order, on the right road of Marxism-Leninism." [82]

Likewise in September 1977 Hoxha wrote that, "The question of Chinese communism has been an enigma to me. I am not saying this only now, but have expressed my doubt years ago in my notes. This doubt arose in my mind immediately after the Bucharest Meeting, and it was aroused because of the timorous stand the Chinese adopted there. ... Khrushchev's activity compelled Teng to change [his conciliatory] report and make it somewhat more severe, because Khrushchev issued a document in which China was attacked, and distributed it before the meeting. Teng was also compelled by the resolute stand of our Party, but that is a long story. The later stands of the Chinese, I am speaking about their political and ideological stands, have shown continuous vacillation, and this was precisely the basis of the enigma and my doubt about them ... but now we can say that this policy of China was a great fraud, a major manoeuvre of the Chinese revisionists to disguise themselves."[83]

In the view of the Albanians, the shift in China's line between 1956 and 1960 was due to the following:

"After the death of Stalin, the Chinese, with Mao Zedong at the head, thought that their time had come ... they wanted to gain as much as they could from Soviet economic aid, in order to become a great power, indeed, an atomic power. But these projects could not be carried out smoothly. If Mao Zedong had his hegemonistic ambitions, Khrushchev and his associates had their expansionist plans, too. ... While making most of what benefit they could get from the Chinese, at the same time Khrushchev and his associates began to be 'cautious' and 'restrained' in their support and aid for them. They did not want China to grow strong, economically or militarily. ... The policy of rapprochement with American imperialism, which Khrushchev was pursuing, likewise, was incompatible with the interests of the Chinese, because that would leave China out of the game of great powers. In this situation, seeing that Khrushchev's line had caused concern in the communist movement, the Communist Party of China seized the opportunity ... seized the 'banner' of defence of the principles of Marxism–Leninism. ... Undoubtedly, not to compel Khrushchev to abandon his course of betrayal of Marxism-Leninism, but to have him accept the hegemony of China and join it in its plans." [84]

As Hoxha put it,

"when Mao Zedong and his associates saw that they would not easily emerge triumphant over the patriarch of modern revisionism, Khrushchev, through the revisionist contest, they changed their tactic, pretended to reject their former flag, presented themselves as 'pure Marxist-Leninists', striving in this way, to win those positions which they had been unable to win with their former tactic. When this second tactic turned out no good, either, they 'discarded' their second, allegedly Marxist-Leninist, flag and came out in the arena as they had always been, opportunists, loyal champions of a line of conciliation and capitulation towards capital and reaction. We were to see all these things confirmed in practice, through a long, difficult and glorious struggle which our Party waged in defence of Marxism–Leninism."[85]

In December 1978, Hoxha's Imperialism and the Revolution was released, the second half of which was a criticism of the "Three Worlds Theory," Chinese foreign policy in general, and Maoism. Hoxha declared that China had become a "social-imperialist" country, aspiring to superpower status alongside the US and USSR by tactically allying with the former against the latter on account of the former's greater economic strength and willingness to invest in the Chinese economy. On the subject of Maoism Hoxha stated that "Mao Zedong was not a Marxist-Leninist, but a progressive revolutionary democrat, who remained for a long time at the head of the Communist Party of China and played an important role in the triumph of the Chinese democratic anti-imperialist revolution. Within China, in the ranks of the party, among the people and outside China, he built up his reputation as a great Marxist-Leninist and he himself posed as a communist, as a Marxist-Leninist dialectician. But this was not so. He was an eclectic who combined some elements of Marxist dialectics with idealism, even with ancient Chinese philosophy."[86]

In a 1988 publication, the Albanians stated that they "appreciated China's aid and its role, among other outside factors, in the development of our country's economy, seeing it as aid by a friendly people, aid without strings attached and without political conditions, which served the general cause of the revolution and socialism." However, "In order to subjugate the PLA and the Albanian state, the Chinese revisionists raised many serious difficulties and obstacles for the fulfilment of the 6th Five-Year Plan [of 1976-1980]. Under various trumped-up excuses, they recalled some of their specialists who worked in Albania, slowed down the rates of work and, especially, postponed the setting up of the industrial projects ... which were planned to be built with the aid of China." Following the split Albania also became a country "relying entirely on its own forces, without any kind of aid or credits from abroad, without external and internal debts."[87]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Hoxha 1984, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Vickers 1999, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Halliday 1986, p. 143.

- ^ Omari & Pollo 1988, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Hoxha 1984, pp. 249–251.

- ^ Hoxha 1984, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Hoxha 1984, pp. 340–346.

- ^ Hoxha 1979a, p. 85.

- ^ Griffith 1963, pp. 27, 29.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 39.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 66.

- ^ Alia 1988, pp. 267–272.

- ^ Hoxha 1984, p. 398.

- ^ Letter, p. 5.

- ^ Griffith 1963, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Vickers 1999, p. 186.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, pp. 45–46.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Halliday 1986, p. 251.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 48.

- ^ Hoxha 1979a, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 57.

- ^ Hoxha 1979a, p. 72.

- ^ a b Letter, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Omari & Pollo 1988, pp. 297–298.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 59.

- ^ Hoxha 1979a, p. 419.

- ^ Omari & Pollo 1988, p. 297.

- ^ Halliday 1986, pp. 252–253.

- ^ Hoxha 1982, pp. 94–113.

- ^ Prifti 1978, pp. 145–147.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 67.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 63.

- ^ Hoxha 1979a, pp. 287–292.

- ^ Letter, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Hoxha 1979a, p. 536.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 91.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 70.

- ^ Hoxha 1979a, pp. 576–577.

- ^ Hoxha 1982, pp. 665–682.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, pp. 92–93.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 71.

- ^ Hoxha 1979a, pp. 593–598.

- ^ Hoxha 1982, p. 698.

- ^ Prifti 1978, p. 245.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 98.

- ^ Hoxha 1979b, p. 41.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 72.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 99.

- ^ Hoxha 1985, p. 693.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, pp. 100–104.

- ^ Hoxha 1979b, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Hoxha 1979b, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 111.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 123.

- ^ Prifti 1978, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Hoxha 1985, p. 110.

- ^ Hoxha 1979b, pp. 334–339.

- ^ Hoxha 1979b, pp. 367–387.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, pp. 125–126.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Hoxha 1985, pp. 696–697.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, pp. 126–128.

- ^ Prifti 1978, p. 253.

- ^ Halliday 1986, p. 254.

- ^ T&P, pp. 14–15, 20–23.

- ^ Hoxha 1979b, pp. 544–545.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, pp. 129–130, 132.

- ^ Hoxha 1979b, p. 715.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Letter, p. 4.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 137.

- ^ Letter, p. 7.

- ^ Letter, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Vickers 1999, p. 203.

- ^ Hoxha 1979b, pp. 760–798.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 138.

- ^ Prifti 1978, p. 255.

- ^ Hoxha 1984, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Hoxha 1979b, pp. 641–642.

- ^ Alia 1988, pp. 253–255.

- ^ Hoxha 1984, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Hoxha 1985, pp. 617–618, 697–698.

- ^ Omari & Pollo 1988, pp. 297, 339, 342.

Sources

[edit]- Letter of the CC of the Party of Labour and the Government of Albania to the CC of the Communist Party and the Government of China (PDF). 8 Nëntori Publishing House. 1978.

- The Theory and Practice of the Revolution (PDF). 8 Nëntori Publishing House. 1977.

- Alia, Ramiz (1988). Our Enver. Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House.

- Biberaj, Elez (1986). Albania and China: A Study of an Unequal Alliance. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Griffith, William E. (1963). Albania and the Sino-Soviet Rift. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press.

- Halliday, Jon, ed. (1986). The Artful Albanian: The Memoirs of Enver Hoxha. London: Chatto & Windus Ltd.

- Hoxha, Enver (1979a). Reflections on China (PDF). Vol. 1. Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House.

- Hoxha, Enver (1979b). Reflections on China (PDF). Vol. 2. Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House.

- Hoxha, Enver (1982). Selected Works (PDF). Vol. 4. Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House.

- Hoxha, Enver (1985). Selected Works (PDF). Vol. 5. Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House.

- Hoxha, Enver (1984). The Khrushchevites (PDF) (Second ed.). Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House.

- O'Donnell, James S. (1999). A Coming of Age: Albania under Enver Hoxha. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Omari, Luan; Pollo, Stefanaq (1988). The History of the Socialist Construction of Albania (PDF). Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House.

- Prifti, Peter R. (1978). Socialist Albania since 1944: Domestic and Foreign Developments. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Vickers, Miranda (1999). The Albanians: A Modern History. New York: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.