Alameda Corridor

| Alameda Corridor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Aerial view showing Alameda Corridor trench in South Los Angeles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Los Angeles County | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | acta | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | freight terminal railroad | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | April 15, 2002 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 20 mi (32 km) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of tracks | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | Largely grade-separated freight railroad | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 40 mph (64 km/h) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

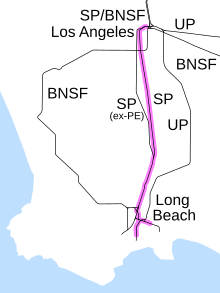

The Alameda Corridor is a 20-mile (32 km) freight rail "expressway"[1] owned by the Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority (reporting mark ATAX) that connects the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach with the transcontinental mainlines of the BNSF Railway and the Union Pacific Railroad that terminate near downtown Los Angeles, California.[2] Running largely in a trench below Alameda Street, the corridor was considered one of the region's largest transportation projects when it was constructed in the 1990s and early 2000s.[1]

Background

[edit]

The railway line along Alameda Street was originally laid out Los Angeles' foundational Los Angeles & San Pedro Railroad, which opened to traffic in 1869.[3] The railroad would go on to be acquired by the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1873, becoming their San Pedro Branch.

A 1984 study by the Ports Advisory Committee recommended the San Pedro Branch be upgraded to meet the growing demands of the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles.[4] At the time, cargo traveling by rail to or from the ports could be routed along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway's Harbor Subdivision or the Southern Pacific's tracks down Alameda Street. The Harbor Subdivision was 90 miles (140 km) long, traveling out to the west side of Los Angeles, before turning back east towards the ports. Meanwhile, the Southern Pacific route had more than 200 street-level railroad crossings where automobiles had to wait for lengthy freight trains to pass.[5] These rail lines were inadequately protected with little more than “wigwag” crossing signals dating from the original construction of the lines. In response, the Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority was established in August 1989 to plan for upgrades along the route.[4]

By the early 1990s, the Southern Pacific was in a difficult financial position and sold the Alameda Street corridor to the Ports of Long Beach for US$235 million in December 1994 ($438 million in 2023 adjusted for inflation).[6][7] This allowed the ACTA to begin building a freight rail "expressway" from the ports to the major rail yards near Downtown Los Angeles. The centerpiece of the new Alameda Corridor would be the "Mid-Corridor Trench" a below-ground, triple-tracked rail line that is 10 miles (16 km) long, 33 feet (10 m) deep, and 50 feet (15 m) wide.[8] The trench and the larger Alameda Corridor would allow freight trains to travel 40 miles per hour (64 km/h) without concerns about grade-crossing collisions or having to blow their horns as they traveled through neighborhoods. The corridor would be open to both BNSF Railway and Union Pacific Railroad (UP) trains via trackage rights.[1]

The line began operation on April 15, 2002, and reached a peak of 60 train movements per day in October 2006.[9] Trains have become much longer since: in 2006, the line carried 19,924 trains carrying 4.9 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) of containers, while in 2021, only 10,928 trains carried the same 4.9 million TEUs.[9] The cost of the line was pegged at $2.1 billion at opening ($3.4 billion in 2023 adjusted for inflation).[3]

In 2013, the railroad carried 33% of the freight traveling to and from the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.[10] Fifteen percent of the nation’s container traffic travels through the corridor according to the Transit Authority.[11]

While the Mid-Corridor trench is the spine of the corridor, the Alameda Corridor Transit Authority also maintains more than 65 miles (105 km) of freight rail track, with 125 turnouts, ten rail bridges, signals at 48 locations, seven grade crossings, and two stormwater pump stations.[12]

Additional developments

[edit]Alameda Corridor–East

[edit]The Alameda Corridor–East project was established in 1998 by the San Gabriel Valley Council of Governments to upgrade over 70 miles (110 km) of railroad tracks in the area east of Downtown Los Angeles. The project includes 19 grade separations and elimination of 23 grade crossings along UP's Alhambra Subdivision and the Los Angeles Subdivision.[13] The crossings, which were previously at grade, tied up traffic on north–south streets for long periods multiple times a day as long freight trains pass en route to and from the UP yards in Vernon and Commerce. As of 2023, over a dozen grade separations have been completed, with several more under construction or in design.[14]

Included as part of the Alameda Corridor–East project is the $336.9 million San Gabriel Trench, which submerged the track between Ramona Street and San Gabriel Boulevard in San Gabriel.[15] Construction began in 2012 and was completed in 2017.[16][17]

Possible electrification

[edit]The Alameda Corridor was built in a way to permit electrification with the use of electric catenary wires, which would increase the environmental benefit by displacing the use of diesel fuel; but the electrification has not happened as of yet.[18] This solution has largely been ignored due to lack of familiarity with electric freight technology in North America, although electric freight trains operate in many other parts of the world. Electrification could reduce air pollution in the region, which has been described as a "Diesel Death Zone" due to the pollution from trucks on Interstate 710.[19][20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Redden, J. W.; Selig, E. T.; Zaremsbki, A. M. (February 2002). "Stiff track modulus considerations". RT&S: Railway Track & Structures. 98 (2): 25–30.

- ^ Uranga, Rachel (October 20, 2016). "How an obscure Alameda Corridor rail agency avoided public accountability laws for years". Long Beach Press Telegram. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ^ a b Rasmussen, Cecilia (April 7, 2002). "New Alameda Corridor Has Historic Roots". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ a b "History". Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ Cerny, L. T. (May 2002). "Alameda corridor opens to traffic in L.A.". RT&S: Railway Track & Structures. 98 (5): 32.

- ^ Zamichow, Nora (September 9, 1993). "Wilson OKs Use of Eminent Domain to Create Railway Corridor: Transit: Governor urges that condemnation be used only as a last resort in talks with Southern Pacific, which wants $260 million for its route between Downtown and the Harbor area". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Railroads: Line sold". Oakland, California. Oakland Tribune. December 30, 1994. p. C1. Retrieved July 13, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fortner, Brian (September 2002). "The Train Lane". Civil Engineering. 72 (9): 52–61.

- ^ a b "Corridor Statistics" (PDF). Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority. March 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ "Is the Alameda Corridor in Trouble?". Railway Age. November 23, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ "Longtime shipping and infrastructure executive takes helm at Alameda Corridor Transportation Authority". City News Service. April 28, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020 – via Long Beach Post.

- ^ "RailWorks Corp. selected to inspect track in Southern California". Intermodal News. AJOT. American Journal of Transportation. August 26, 2019. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ "Alameda Corridor-East Construction Authority Project Overview". Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ^ "ACE Project Schedule". San Gabriel Valley Council of Governments. June 4, 2023. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ^ Ortega, Fred (April 10, 2008). "State OKs funds for San Gabriel crossing". Pasadena Star News. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012.

- ^ Aragon, Greg (December 11, 2015). "$1.6 billion Alameda Corridor-East Construction Project Gets Boost from CTC". Engineering News-Record.

- ^ Pool, Bob (February 6, 2012). "At a planned train trench, an archaeological treasure trove". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- ^ Frank, Myra. "Alameda Corridor Environmental Impact Report" (PDF). LA Metro Archives. Myra L. Franks & Associates, Inc. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ Yanity, Brian (July 29, 2018). "The Potential of Electric Freight Rail in Southern California" (PDF). Californians for Electric Rail.

- ^ Nelson, Laura (March 1, 2018). "710 Freeway is a 'diesel death zone' to neighbors — can vital commerce route be fixed?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 11, 2020.