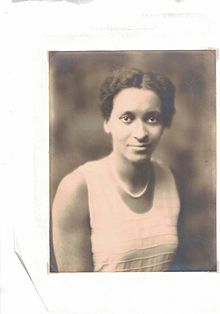

Agnes Yewande Savage

Agnes Yewande Savage | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 February 1906 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 7 September 1964 (aged 58) Hemel Hempstead, England |

| Nationality | |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | Physician |

| Known for |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Richard Gabriel Akinwande Savage (brother) |

Agnes Yewande Savage (21 February 1906 – 7 September 1964)[1] was a Nigerian medical doctor and the first West African woman to train and qualify in orthodox medicine.[2][3][4][5][6] Savage was the first West African woman to receive a university degree in medicine, graduating with first-class honours from the University of Edinburgh in 1929 at the age of 23.[2][4] In 1933, Sierra Leonean political activist and higher education pioneer, Edna Elliott-Horton became the second West African woman university graduate and the first to earn a bachelor's degree in the liberal arts.[7]

Life

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Savage was born on 21 February 1906 in Edinburgh, Scotland, to Richard Akinwande Savage Sr (a Nigerian medical doctor, newspaper publisher and a 1900 Edinburgh graduate of Sierra Leone Creole descent) and Maggie S. Bowie (a working-class Scotswoman).[2] Her brother was Richard Gabriel Akinwande Savage, also a doctor who graduated from Edinburgh in 1926.[2] Savage passed exams to the Royal College of Music in 1919 and was given a scholarship to study at George Watson's Ladies College.[2] There, she received an award for General Proficiency in Class Work and passed the Scottish Higher Education Leaving Certificate.[2][3][5]

She entered Edinburgh University to study medicine and she excelled in her studies. In her fourth year of medical school, she obtained first-class honours in all subjects, won a prize in Diseases of the Skin and a medal in Forensic Medicine, making her the first woman in the history of Edinburgh to do so.[2][a][8][9] She was awarded the Dorothy Gilfillan Memorial Prize as the best woman graduate in 1929.[2]

Medical career and legacy

[edit]Savage faced gender and racial institutional barriers in her career.[2] After graduation, she joined the colonial service in the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana) as a Junior Medical Officer. Though better qualified than most of her male counterparts, she received fewer benefits.[2][3]

In 1931, she was recruited by the headmaster of Achimota College. At the urging of the headmaster, Alec Garden Fraser, the colonial government gave her a better contract. She was with Achimota for four years as a medical officer and a teacher.[2] While at Achimota, she came into contact with Susan de Graft-Johnson when the latter was the Girls' School Prefect. Johnson regularly worked with Savage at the sick bay[10] and later went on to also study medicine at the University of Edinburgh, becoming Ghana's first female medical doctor.[7] Another West African woman medical pioneer who studied at both Achimota and Edinburgh was Matilda J. Clerk, who became the first Ghanaian woman to win a university merit scholarship, the second female doctor in Ghana and the fourth West African woman to train as a physician.[5][7]

After Achimota, Savage went back to the colonial medical service and was given a better concession, in charge of the infant welfare clinics, associated with Korle Bu Hospital in Accra. Concurrently, she was appointed the assistant medical officer to the maternity department of the hospital and warden of the nurses' hostel. At Korle-Bu, she supervised the establishment of a training school for nurses, Korle-Bu Nurses Training College, where a ward was named in her honour.[2][3]

Death

[edit]Savage retired relatively early due to "physical and psychological exhaustion" in 1947 and spent the remainder of her life in Scotland raising her niece and nephew. She died following a stroke, in St Paul's Hospital, Hemel Hempstead, England, on 7 September 1964, aged 58.[6][11]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ A newspaper report of the graduation ceremonies noted: "Among the 95 medical graduates, was a young lady of colour from West Africa, bearing the not inappropriate name Agnes Yewande Savage, whose father is also a doctor. She gained the two prizes awarded to the most distinguished woman student of her year, and her success, to judge from her enthusiastic reception, was highly popular with her fellow undergraduates."

References

[edit]- ^ "Deaths". The Times. 10 September 1964. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Mitchell, Henry (November 2016). "Dr Agnes Yewande Savage – West Africa's First Woman Doctor (1906–1964)". Centre of African Studies. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d "CAS Students to Lead Seminar on University's African Alumni, Pt. IV: Agnes Yewande Savage". CAS from the Edge. 16 November 2016. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ a b Tetty, Charles (1985). "Medical Practitioners of African Descent in Colonial Ghana". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 18 (1): 139–144. doi:10.2307/217977. JSTOR 217977. PMID 11617203.

- ^ a b c "Agnes Yewande Savage (1906 – 1964)". The University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ a b Ferry, Georgina (November 2018). "Agnes Yewande Savage, Susan Ofori-Atta, and Matilda Clerk: three pioneering doctors". The Lancet. 392 (10161): 2258–2259. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32827-7. ISSN 0140-6736. S2CID 53713242.

- ^ a b c Patton, Adell Jr. (13 April 1996). Physicians, Colonial Racism, and Diaspora in West Africa (1st ed.). Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813014326.

- ^ "Edinburg Graduations". The Townsville Daily Bulletin. 9 September 1929. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dee, Henry. "Agnes Yewande Savage – 1929". UncoverED. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Vieta, K. T. (1999). The Flagbearers of Ghana: Profiles of one hundred distinguished Ghanaians. Accra, Ghana: Ena Pubs.

- ^ "Deaths". The Daily Telegraph. 10 September 1964. p. 32 – via Newspapers.com.

- Savage family (Lagos)

- 1906 births

- 1964 deaths

- 20th-century Nigerian medical doctors

- 20th-century Nigerian women

- 20th-century women physicians

- Alumni of the Royal College of Music

- Alumni of the University of Edinburgh Medical School

- Black British health professionals

- Black British history

- Black British scientists

- Black British women scientists

- 20th-century British women scientists

- British expatriates in Ghana

- Medical doctors from Gold Coast (British colony)

- History of women in Nigeria

- Medical doctors from Edinburgh

- Nigerian expatriates in Ghana

- Nigerian people of Scottish descent

- Nigerian women medical doctors

- Saro people

- Scottish people of Nigerian descent

- Scottish people of Sierra Leonean descent

- Scottish people of Yoruba descent

- Sierra Leone Creole people

- University and college founders

- Yoruba physicians

- Yoruba women physicians