Agama (Hinduism)

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

The Agamas (Devanagari: आगम, IAST: āgama) (Tamil: ஆகமம், romanized: ākamam) (Bengali: আগম, ISO15919: āgama) are a collection of several Tantric literature and scriptures of Hindu schools.[1][2] The term literally means tradition or "that which has come down", and the Agama texts describe cosmology, epistemology, philosophical doctrines, precepts on meditation and practices, four kinds of yoga, mantras, temple construction, deity worship and ways to attain sixfold desires.[1][3] These canonical texts are in Sanskrit[1] and Tamil.[4][5]

The three main branches of Agama texts are Shaiva, Vaishnava and Shakta.[1] The Agamic traditions are sometimes called Tantrism,[6] although the term "Tantra" is usually used specifically to refer to Shakta Agamas.[7][8] The Agama literature is voluminous, and includes 28 Shaiva Agamas, 64 Shakta Agamas (also called Tantras), and 108 Vaishnava Agamas (also called Pancharatra Samhitas), and numerous Upa-Agamas.[9]

The origin and chronology of Agamas is unclear. Some are Vedic and others non-Vedic.[10] Agama traditions include Yoga and Self Realization[clarification needed] concepts, some include Kundalini Yoga,[11] asceticism, and philosophies ranging from Dvaita (dualism) to Advaita (monism).[12][13] Some suggest that these are post-Vedic texts, others as pre-Vedic compositions dating back to over 1100 BCE.[14][15][16] Epigraphical and archaeological evidence suggests that Agama texts were in existence by about middle of the 1st millennium CE, in the Pallava dynasty era.[17][18]

Scholars note that some passages in the Hindu Agama texts appear to repudiate the authority of the Vedas, while other passages assert that their precepts reveal the true spirit of the Vedas.[2][19][20] The Agamas literary genre may also be found in Śramaṇic traditions (i.e. Buddhist, Jains, etc).[21][22] Bali Hindu tradition is officially called Agama Hindu Dharma in Indonesia.[23]

Etymology

[edit]Āgama (Sanskrit आगम) is derived from the verb root गम् (gam) meaning "to go" and the preposition आ (ā) meaning "toward" and refers to scriptures as "that which has come down".[1]

Agama literally means "tradition",[1] and refers to precepts and doctrines that have come down as tradition.[8] Agama, states Dhavamony, is also a "generic name of religious texts which are at the basis of Hinduism".[8] Other terms used for these texts can include saṃhitā (“collection”), sūtra (“aphorism”), or tantra ("system"), with the term "tantra" utilized more frequently for Shakta agamas, than for Shaiva or Vaishnava agamas.[24][8]

Significance

[edit]

Agamas are structured dialogically, often as conversations between Śiva and Śakti.[25] This dialogical format between divinities contrasts with the monologue of revelation from a single divine being to a recipient at a single place and time. This format is significant as it instead portrays spiritual insight as always ongoing, an eternal and dynamic conversation which seekers can enter into with the right cultivation of awareness.[25] Agamas, states Rajeshwari Ghose, teach a system of spirituality involving ritual worship and ethical personal conduct through the precepts of a particular deity.[26] The means of worship in the Agamic religions differs from the Vedic form. While the Vedic form of yajna requires no icons and shrines, the Agamic religions are based on icons with puja as a means of worship.[26] Symbols, icons and temples are a necessary part of the Agamic practice, while non-theistic paths are alternative means of Vedic practice.[26] Action and will drive Agama precepts, while knowledge is salvation in Vedic precepts.[26] This, however, does not necessarily mean that Agamas and Vedas are opposed, according to medieval-era Hindu theologians. Tirumular, for example, explained their link as follows: "the Vedas are the path, and the Agamas are the horse".[26][27]

Each Agama consists of four parts:[12][26]

- Jnana pada, also called Vidya pada[12] – consists of doctrine, the philosophical and spiritual knowledge, knowledge of reality and liberation.

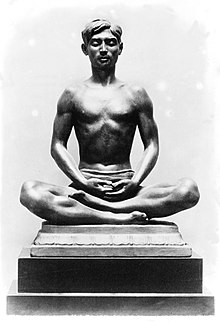

- Yoga pada – precepts on yoga, the physical and mental discipline.

- Kriya pada – consists of rules for rituals, construction of temples (Mandir); design principles for sculpting, carving, and consecration of idols of deities for worship in temples;[28] for different forms of initiations or diksha. This code is analogous to those in Puranas and in the Buddhist text of Sadhanamala.[12]

- Charya pada – lays down rules of conduct, of worship (puja), observances of religious rites, rituals, festivals and prayaschittas.

The Agamas state three requirements for a place of pilgrimage: Sthala, Tirtha, and Murti. Sthala refers to the place of the temple, Tīrtha is the temple tank, and Murti refers to the image of god (usually an icon of a deity).[citation needed]

Elaborate rules are laid out in the Agamas for Silpa (the art of sculpture) describing the quality requirements of the places where temples are to be built, the kind of images to be installed, the materials from which they are to be made, their dimensions, proportions, air circulation, lighting in the temple complex, etc.[28] The Manasara and Silpasara are some of the works dealing with these rules. The rituals followed in worship services each day at the temple also follow rules laid out in the Agamas.

Philosophy

[edit]The Agama texts of Hinduism present a diverse range of philosophies, ranging from theistic dualism to absolute monism.[13][30] This diversity of views was acknowledged in Chapter 36 of Tantraloka by the 10th-century scholar Abhinavagupta.[13] In Shaivism alone, there are ten dualistic (dvaita) Agama texts, eighteen qualified monism-cum-dualism (bhedabheda) Agama texts, and sixty-four monism (advaita) Agama texts.[31] The Bhairava Shastras are monistic, while Shiva Shastras are dualistic.[32][33]

A similar breadth of diverse views is present in Vaishnava Agamas as well. The Agama texts of Shaiva and Vaishnava schools are premised on existence of Atman (soul, self) and the existence of an Ultimate Reality (Brahman – called Shiva in Shaivism, and Vishnu in Vaishnavism).[34] The texts differ in the relation between the two. Some assert the dualistic philosophy of the individual soul and Ultimate Reality being different, while others state a Oneness between the two.[34] Kashmir Shaiva Agamas posit absolute oneness, that is God (Shiva) is within man, God is within every being, God is present everywhere in the world including all non-living beings, and there is no spiritual difference between life, matter, man and God. The parallel group among Vaishnavas are the Shuddhadvaitins (pure Advaitins).[34]

Scholars from both schools have written treatises ranging from dualism to monism. For example, Shivagrayogin has emphasized the non-difference or unity of being (between the Atman and Shivam), which is realized through stages which include rituals, conduct, personal discipline and the insight of spiritual knowledge.[35] This bears a striking similarity, states Soni, to Shankara, Madhva and Ramanujan Vedantic discussions.[35]

Relation to the Vedas and Upanishads

[edit]The Vedas and Upanishads are common scriptures of Hinduism, states Dhavamony, while the Agamas are sacred texts of specific sects of Hinduism.[8] The surviving Vedic literature can be traced to the 1st millennium BCE and earlier, while the surviving Agamas can be traced to 1st millennium of the common era.[8] The Vedic literature, in Shaivism, is primary and general, while Agamas are special treatise. In terms of philosophy and spiritual precepts, no Agama that goes against the Vedic literature, states Dhavamony, will be acceptable to the Shaivas.[8] Similarly, the Vaishnavas treat the Vedas along with the Bhagavad Gita as the main scripture, and the Samhitas (Agamas) as exegetical and exposition of the philosophy and spiritual precepts therein.[8] The Shaktas have a similar reverence for the Vedic literature and view the Tantras (Agamas) as the fifth Veda.[8]

The heritage of the Agamas, states Krishna Shivaraman, was the "Vedic piety maturing in the monism of the Upanishads presenting the ultimate spiritual reality as Brahman and the way to realizing as portrayed in the Gita".[36]

The Veda is the cow, the true Agama its milk.

— Umapati, Translated by David Smith[37]

Texts

[edit]Shaiva and Shakta Agamas

[edit]There are multiple frameworks for organizing the agamas. One of which, building on distinctions introduced by Abhinavagupta, places the Shaiva and Shakta agamas on a continuum from those that are dualistic, Śiva-centered, and non-transgressive to those that are non-dualistic, Śakti-centered, and transgressive.[38] In this framework, the Śaiva Siddhānta agamas (which can be subdivided into 10 Śaiva and 18 Rudra āgamas, arranged into a common list of 28 āgamas below) feature on the dualistic, Śiva-centered, and non-transgressive side. In the middle falls the 64 Bhairava agamas (which can be subdivided into the Amṛteśvara and Mantrapīṭha). And, on the most non-dualistic, Śakti-centered, and transgressive side are the Vidyapīṭha tantras (including the Yāmalas, Trika, and Kālīkula). In this way, the Shakta Agamas are inextricably related to the Shaiva Agamas, with their respective focus on Shakti with Shiva in Shakta Tantra and on Shiva in Shaiva texts.[39] DasGupta states that the Shiva and Shakti are "two aspects of the same truth – static and dynamic, transcendent and immanent, male and female", and neither is real without the other, Shiva's dynamic power is Shakti and she has no existence without him, she is the highest truth and he the manifested essence.[39]

- Kamikam

- Yogajam

- Chintyam

- Karanam

- Ajitham

- Deeptham

- Sukskmam

- Sahasram

- Ashuman

- Suprabedham

- Vijayam

- Nishwasam

- Swayambhuvam

- Analam

- Veeram

- Rouravam

- Makutam

- Vimalam

- Chandragnanam

- Bimbam

- Prodgeetham

- Lalitham

- Sidham

- Santhanam

- Sarvoktham

- Parameshwaram

- Kiranam

- Vathulam

Shaiva Siddhanta

[edit]The Shaiva Agamas led to the Shaiva Siddhanta philosophy in Tamil-speaking regions of South India. Of the 28 agamas, the Pārameśa, Niśvāsa, Svāyambhuva[sūtrasaṅgraha], Raurava[sūtrasaṅgraha], Kiraṇa, and Par[ākhya]/Saurabheya all have surviving copies that are demonstrably pre-twelfth century.[41] Many of these agamas have been translated and published by the Himalayan Academy.[42] The Shaiva Siddhanta also relies on four agamas that do not figure into this canonical list of 28 (the Kālottara, Mataṅga-pārameśvara, Mṛgendra, and Sarvajñānottara) along with two pratiṣṭhā-tantras (Mayasaṅgraha and Mohacūḍottara).[41] The writings of Tirumular and the lineage of Siddhars, such as those compiled in the Tirumurai, also play a crucial textual role in this tradition. In the Siddhanta, āgamās are seen as the twofold wisdom of Śiva, consisting of mantra and realization, that liberates the individual selves from the threefold bondage of mala, māyā, and karma.[25]

Kashmir Shaivism

[edit]The Kashmir Shaivism lineage draws freely upon the 10 Saiva, 18 Rudra, and 64 Bhairava agamas, seeing them as a progression from dualistic, partially non-dualistic, and non-dualistic, while also integrating the Śakta tantras. Of the Bhairava agamas, two agamas stand out in their importance: the Netra Tantra of the Amṛteśvara set of agamas and the Svacchanda Tantra of the Mantrapīṭha set of agamas.[38] Both were commented upon freely by Kashmiri Shaiva exegetes, like Kṣemarāja and continue to have practical importance to this day.[43] From the Shakta tantras, Kashmir Shaivism draws primarily on Trika texts, primarily Mālinīvijayottara, as well as the Siddhayogeśvarīmata, Tantrasadbhāva, Parātrīśikā, and Vijñāna Bhairava.[43] Abhinavgupta and Kṣemarāja regard āgamas non-dualistically, as the self-revealing act of Śiva, who assumes the roles of preceptor and disciple, and reveals Tantra according to the interests of different subjects. The āgamas are thereby further equated with prakāśa-vimarśa, the capacity of consciousness to reflect back upon itself through its own expressions.[25] The literature of Kashmir Shaivism is divided under three categories: Agama shastra, Spanda shastra, and Pratyabhijna shastra.[44] In addition to these agamas, Kashmir Shaivism further relies on exegetical work developing Vasugupta's (850 AD) influential Shiva Sutras that inaugurated the spanda tradition[45][44] and Somananda's (875–925 CE) Śivadṛṣṭi, which set the stage for the pratyabhijñā tradition.[46][47] These texts are both said to be revealed under spiritual circumstances. For instance, Kallata in Spanda-vritti and Kshemaraja in his commentary Vimarshini state Shiva revealed the secret doctrines to Vasugupta while Bhaskara in his Varttika says a Siddha revealed the doctrines to Vasugupta in a dream.[45]

Shakta Agamas

[edit]

The Shakta Agamas are commonly known as Tantras,[8][9] and they are imbued with reverence for the feminine, representing goddess as the focus and treating the female as equal and essential part of the cosmic existence.[39] The feminine Shakti (literally, energy and power) concept is found in the Vedic literature, but it flowers into extensive textual details only in the Shakta Agamas. These texts emphasize the feminine as the creative aspect of a male divinity, cosmogonic power and all pervasive divine essence. The theosophy, states Rita Sherma, presents the masculine and feminine principle in a "state of primordial, transcendent, blissful unity".[39] The feminine is the will, the knowing and the activity, she is not only the matrix of creation, she is creation. Unified with the male principle, in these Hindu sect's Tantra texts, the female is the Absolute.[39]

The Shakta Agamas or Shakta tantras are 64 in number.[9] Krishnananda Agamavagisha has compiled 64 agamas in a single volume named Brihat Tantrasara.[48] Some of the older Tantra texts in this genre are called Yamalas, which literally denotes, states Teun Goudriaan, the "primeval blissful state of non-duality of Shiva and Shakti, the ultimate goal for the Tantric Sadhaka".[49]

The Shakta tantras, each of which emphasize a different goddess, developed into several transmissions (āmnāyas), which, in turn, are connected symbolically with one of the four, five, or six directional faces of Shiva, depending on the text being consulted.[50][51] When counted in four directions, these transmissions include the Pūrvāmnāya (Eastern transmission) featuring the Trika goddesses of Parā, Parāparā and Aparā, the Uttarāmnāya (Northern transmission) featuring the Kālikā Krama, the Paścimāmnāya (Western transmission) featuring the humpbacked goddess Kubjikā and her consort Navātman, and the Dakṣiṇāmnāya (Southern transmission) featuring the goddess Tripurasundarī and Sri Vidya. In Nepal, these transmissions have not only been preserved among the Newar tantric community, but as early as the 12th century, these transmissions were arranged into a sequence of practice within the Sarvāmnāya tradition.[52][53] In the Sarvāmnāya tradition, initiates are sequentially initiated into each of the transmissions, where they learn to integrate each goddess with all the others, to understand and experience Shakti holistically.[52][53]

Vaishnava Agamas

[edit]The Vaishnava Agamas are found into two main schools – Pancharatra and Vaikhanasas. While Vaikhanasa Agamas were transmitted from Vikhanasa Rishi to his disciples Brighu, Marichi, Atri and Kashyapa, the Pancharatra Agamas are classified into three: Divya (from Vishnu), Munibhaashita (from Muni, sages), and Aaptamanujaprokta (from sayings of trustworthy men).[1]

Vaikhanasa Agama

[edit]Maharishi Vikhanasa is considered to have guided in the compilation of a set of Agamas named Vaikhānasa Agama. Sage Vikhanasa is conceptualized as a mind-born creation, i.e., Maanaseeka Utbhavar of Lord Narayana.[54] Originally Vikhanasa passed on the knowledge to nine disciples in the first manvantara -- Atri, Bhrigu, Marichi, Kashyapa, Vasishta, Pulaha, Pulasthya, Krathu and Angiras. However, only those of Bhrigu, Marichi, Kashyapa and Atri are extant today. The four rishis are said to have received the cult and knowledge of Vishnu from the first Vikahansa, i.e., the older Brahma in the Svayambhuva Manvanthara. Thus, the four sages Atri, Bhrigu, Marichi, Kashyapa, are considered the propagators of vaikhānasa śāstra. A composition of Sage Vikhanasa's disciple Marichi, namely, Ananda-Samhita states Vikhanasa prepared the Vaikhanasa Sutra according to a branch of Yajurveda and was Brahma himself.[54]

The extant texts of vaikhānasa Agama number 28 in total and are known from the texts, vimānārcakakalpa and ānanda saṃhitā, both composed by marīci which enumerate them. They are:[55][56]

The 13 Adhikaras authored by Bhrigu are khilatantra, purātantra, vāsādhikāra, citrādhikāra, mānādhikāra, kriyādhikāra, arcanādhikāra, yajnādhikāra, varṇādhikāra, prakīrnṇādhikāra, pratigrṛhyādhikāra, niruktādhikāra, khilādhikāra. However, ānanda saṃhitā attributes ten works to Bhrigu, namely, khila, khilādhikāra, purādhikāra, vāsādhikāraṇa, arcanādhikaraṇa, mānādhikaraṇa, kriyādhikāra, niruktādhikāra, prakīrnṇādhikāra, yajnādhikāra.[citation needed]

The 8 Samhitas authored by Mareechi are Jaya saṃhitā, Ananda saṃhitā, Saṃjnāna saṃhitā, Vīra saṃhitā, Vijaya saṃhitā, Vijita saṃhitā, Vimala saṃhitā, Jnāna saṃhitā. However, ānanda saṃhitā attributes the following works to Marichi—jaya saṃhitā, ānanda saṃhitā, saṃjnāna saṃhitā, vīra saṃhitā, vijaya saṃhitā, vijita saṃhitā, vimala saṃhitā, kalpa saṃhitā.[citation needed]

The 3 Kandas authored by Kashyapa are Satyakāṇḍa, Tarkakāṇḍa, Jnānakāṇḍa. However, Ananda Saṃhitā attributes the satyakāṇḍa, karmakāṇḍa and jnānakāṇḍa to Kashyapa.[citation needed]

The 4 tantras authored by Atri are Pūrvatantra, Atreyatantra, Viṣṇutantra, Uttaratantra.[citation needed] However, Ananda Saṃhitā attributes the pūrvatantra, viṣṇutantra, uttaratantra and mahātantra to Atri.[citation needed]

Pancharatra Agama

[edit]Like the Vaikhanasa Agama, the Pancharatra Agama, the Viswanatha Agama is centered around the worship of Lord Vishnu. While the Vaikhansa deals primarily with Vaidhi Bhakti, the Pancharatra Agama teaches both vaidhi and Raganuga bhakti.[57]

Soura Agamas

[edit]The Soura or Saura Agamas comprise one of the six popular agama-based religions of Shaiva, Vaishnava, Shakta, Ganapatya, Kaumara and Soura. The Saura Tantras are dedicated to the sun (Surya) and Soura Agamas are in use in temples of Sun worship.

Ganapatya Agamas

[edit]The Paramanada Tantra mentions the number of sectarian tantras as 6000 for Vaishnava, 10000 for Shaiva, 100000 for Shakta, 1000 for Ganapatya, 2000 for Saura, 7000 for Bhairava, and 2000 for Yaksha-bhutadi-sadhana.[7]

History and chronology

[edit]The chronology and history of Agama texts is unclear.[18] The surviving Agama texts were likely composed in the 1st millennium CE, likely existed by the 5th century CE.[18] However, scholars such as Ramanan refer to the archaic prosody and linguistic evidence to assert that the beginning of the Agama literature goes back to about 5th century BCE, in the decades after the death of Buddha.[8][18][58]

Temple and archaeological inscriptions, as well as textual evidence, suggest that the Agama texts were in existence by the 7th century in the Pallava dynasty era.[17] However, Richard Davis notes that the ancient Agamas "are not necessarily the Agamas that survive in modern times". The texts have gone through revision over time.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Grimes, John A. (1996). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3068-2. LCCN 96012383. pages 16–17

- ^ a b Julius Lipner (2004), Hinduism: the way of the banyan, in The Hindu World (Editors: Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-21527-7, pages 27–28

- ^ Mariasusai Dhavamony (2002), Hindu-Christian Dialogue, Rodopi, ISBN 978-90-420-1510-4, pages 54–56

- ^ Indira Peterson (1992), Poems to Siva: The Hymns of the Tamil Saints, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-81-208-0784-6, pages 11–18

- ^ A Datta (1987), Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: A-Devo, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 978-0-8364-2283-2, page 95

- ^ Wojciech Maria Zalewski (2012), The Crucible of Religion: Culture, Civilization, and Affirmation of Life, Wipf and Stock Publishers, ISBN 978-1-61097-828-6, page 128

- ^ a b Banerji, S. C. (2007). A Companion To Tantra. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-402-3 [1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mariasusai Dhavamony (1999), Hindu Spirituality, Gregorian University and Biblical Press, ISBN 978-88-7652-818-7, pages 31–34 with footnotes

- ^ a b c Klaus Klostermaier (2007), A Survey of Hinduism: Third Edition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4, pages 49–50

- ^ PT Raju (2009), The Philosophical Traditions of India, Routledge, ISBN 978-81-208-0983-3, page 45; Quote: The word Agama means 'coming down', and the literature is that of traditions, which are mixtures of the Vedic with some non-Vedic ones, which were later assimilated to the Vedic.

- ^ Singh, L. P. (2010). Tantra, Its Mystic and Scientific Basis, Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-8069-640-4

- ^ a b c d e Jean Filliozat (1991), Religion, Philosophy, Yoga: A Selection of Articles, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0718-1, pages 68–69

- ^ a b c Richard Davis (2014), Ritual in an Oscillating Universe: Worshipping Siva in Medieval India, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-60308-7, page 167 note 21, Quote (page 13): "Some agamas argue a monist metaphysics, while others are decidedly dualist. Some claim ritual is the most efficacious means of religious attainment, while others assert that knowledge is more important."

- ^ Guy Beck (1993), Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound, University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 978-0-87249-855-6, pages 151–152

- ^ Tripath, S.M. (2001). Psycho-Religious Studies Of Man, Mind And Nature. Global Vision Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-87746-04-1

- ^ Drabu, V. N. (1990). Śaivāgamas: A Study in the Socio-economic Ideas and Institutions of Kashmir (200 B.C. to A.D. 700), Indus Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-85182-38-4. LCCN lc90905805

- ^ a b c Richard Davis (2014), Worshiping Śiva in Medieval India: Ritual in an Oscillating Universe, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-60308-7, pages 12–13

- ^ a b c d Hilko Wiardo Schomerus and Humphrey Palmer (2000), Śaiva Siddhānta: An Indian School of Mystical Thought, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1569-8, pages 7–10

- ^ For examples of Vaishnavism Agama text verses praising Vedas and philosophy therein, see Sanjukta Gupta (2013), Lakṣmī Tantra: A Pāñcarātra Text, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1735-7, pages xxiii-xxiv, 96, 158–159, 219, 340, 353 with footnotes, Quote: "In order not to dislocate the laws of dharma and to maintain the family, to govern the world without disturbance, to establish norms and to gratify me and Vishnu, the God of gods, the wise should not violate the Vedic laws even in thought – The Secret Method of Self-Surrender, Lakshmi Tantra, Pāñcarātra Agama".

- ^ For examples in Shaivism literature, see T Isaac Tambyah (1984), Psalms of a Saiva Saint, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 978-81-206-0025-6, pages xxii-xxvi

- ^ Helen Baroni (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8239-2240-6, page 3

- ^ Tigunait, Rajmani (1998), Śakti, the Power in Tantra: A Scholarly Approach, Himalayan Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-89389-154-1. LCCN 98070188

- ^ June McDaniel (2010), Agama Hindu Dharma Indonesia as a New Religious Movement: Hinduism Recreated in the Image of Islam, Nova Religio, Vol. 14, No. 1, pages 93–111

- ^ Padoux, André (2017). The Hindu Tantric world: an overview. Chicago (Ill.) London: The University of Chicago press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-226-42393-7.

- ^ a b c d Timalsina, S. (2014-05-01). "The Dialogical Manifestation of Reality in Āgamas". The Journal of Hindu Studies. 7 (1): 6–24. doi:10.1093/jhs/hiu006. ISSN 1756-4255.

- ^ a b c d e f Ghose, Rajeshwari (1996). The Tyāgarāja Cult in Tamilnāḍu: A Study in Conflict and Accommodation. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. ISBN 81-208-1391-X. [2]

- ^ Thomas Manninezhath (1993), Harmony of Religions: Vedānta Siddhānta Samarasam of Tāyumānavar, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1001-3, page 135

- ^ a b c V Bharne and K Krusche (2012), Rediscovering the Hindu Temple: The Sacred Architecture and Urbanism of India, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4438-4137-5, pages 37–42

- ^ Archana Verma (2012), Temple Imagery from Early Mediaeval Peninsular India, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4094-3029-2, pages 150–159, 59–62

- ^ DS Sharma (1990), The Philosophy of Sadhana, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-0347-1, pages 9–14

- ^ Mark Dyczkowski (1989), The Canon of the Śaivāgama, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0595-8, pages 43–44

- ^ JS Vasugupta (2012), Śiva Sūtras, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0407-4, pages 252, 259

- ^ Gavin Flood (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0, pages 162–167

- ^ a b c Ganesh Tagare (2002), The Pratyabhijñā Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1892-7, pages 16–19

- ^ a b Jayandra Soni (1990), Philosophical Anthropology in Śaiva Siddhānta, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0632-8, pages 178–181, 209–214

- ^ Krishna Sivaraman (2008), Hindu Spirituality Vedas Through Vedanta, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1254-3, page 263

- ^ David Smith (1996), The Dance of Siva: Religion, Art and Poetry in South India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-48234-9, page 116

- ^ a b Sanderson, A. (1991). "The World's Religions: The Religions of Asia". Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-98545-8.

- ^ a b c d e Rita Sherma (2000), Editors: Alf Hiltebeitel and Kathleen M Erndl, Is the Goddess a Feminist?: The Politics of South Asian Goddesses, New York University Press, ISBN 978-0-8147-3619-7, pages 31–49

- ^ Teun Goudriaan (1981), Hindu Tantric and Śākta Literature, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02091-6, page 36

- ^ a b Goodall, Dominic (2004). Parākhyatantram: the Parākhyatantra: a scripture of the Śaiva Siddhānta. Collection Indologie. Pondichéry: Institut Français de Pondichéry [u.a.] pp. xxiii–xxv. ISBN 978-2-85539-642-2.

- ^ "Agamas". www.himalayanacademy.com. Retrieved 2024-02-06.

- ^ a b Sanderson, A. (2007). "Mélanges tantriques à la mémoire d'Hélène Brunner / Tantric Studies in Memory of Hélène Brunner". In Goodall, D., Padoux, A. (eds.). The Śaiva Exegesis of Kashmir. Institut français d’Indologie / École française d’Extrême-Orient. pp. 231–442.

- ^ a b Sharma, D.S. (1983). The Philosophy of Sādhanā: With Special Reference to the Trika Philosophy of Kashmir. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0347-1. LCCN lc89027739 [3]

- ^ a b Singh, J. (1979). Śiva Sūtras: The Yoga of Supreme Identity : Text of the Sūtras and the Commentary Vimarśinī of Kṣemarāja Translated Into English with Introduction, Notes, Running Exposition, Glossary and Index. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. ISBN 978-81-208-0407-4. LCCN lc79903550. [4]

- ^ Somānanda; Utpaladeva; Nemec, John; Somānanda (2011). The ubiquitous Śiva: Somānanda's Śivadṛṣṭi and his tantric interlocutors. AAR Religion in translation. New York, NY Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979545-1.

- ^ Pandit, B. N. (1990). History of Kashmir Saivism. Srinagar: Utpal Publications. ISBN 978-81-85217-01-7.

- ^ Tarkalankar, Chandrakumar (1932). Brihat Tantrasar.

- ^ Teun Goudriaan (1981), Hindu Tantric and Śākta Literature, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-02091-6, pages 39–40

- ^ Padoux, André (2017). The Hindu Tantric world: an overview. Chicago (Ill.) London: The University of Chicago press. ISBN 978-0-226-42393-7.

- ^ Dyczkowski, Mark S. G. (1988). The canon of the Śaivāgama and the Kubjikā Tantras of the western Kaula tradition. The SUNY series in the Shaiva traditions of Kashmir. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-491-3.

- ^ a b "Our Tradition". Vimarsha Foundation. Retrieved 2024-02-06.

- ^ a b Lidke, J. (2004). "The transmission of all powers: Sarvāmnāya Śākta Tantra and the semiotics of power in Nepāla-maṇḍala". The Pacific World. 6: 257–291.

- ^ a b SrI Ramakrishna Deekshitulu and SrImAn VaradAccAri SaThakOpan Swami. SrI VaikhAnasa Bhagavad SAstram [5] Archived 2012-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Vaikhanasa Agama Books". Archived from the original on 2011-03-19. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ^ Venkatadriagaram Varadachari (1982). Agamas and South Indian Vaisnavism. Prof M Rangacharya Memorial Trust.

- ^ Awakened India, Volume 112, Year 2007, p.88, Prabuddha Bharata Office.

- ^ DeCaroli, Robert (2004). Haunting the Buddha: Indian Popular Religions and the Formation of Buddhism. Oxford University Press, US. ISBN 978-0-19-516838-9.

Sources

[edit]- Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami (November 2003) [1979]. "Glossary". Dancing with Shiva, Hinduism's Contemporary Catechism (Sixth ed.). Kapaa, HI: Himalayan Academy. p. 755. ISBN 0-945497-96-2. Retrieved 2006-04-04.