Nativity of Jesus in art

The Nativity of Jesus has been a major subject of Christian art since the 4th century.

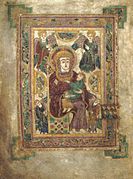

The artistic depictions of the Nativity or birth of Jesus, celebrated at Christmas, are based on the narratives in the Bible, in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, and further elaborated by written, oral and artistic tradition. Christian art includes a great many representations of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child. Such works are generally referred to as the "Madonna and Child" or "Virgin and Child". They are not usually representations of the Nativity specifically, but are often devotional objects representing a particular aspect or attribute of the Virgin Mary, or Jesus. Nativity pictures, on the other hand, are specifically illustrative, and include many narrative details; they are a normal component of the sequences illustrating both the Life of Christ and the Life of the Virgin.

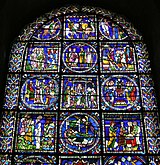

The Nativity has been depicted in many different media, both pictorial and sculptural. Pictorial forms include murals, panel paintings, manuscript illuminations, stained glass windows and oil paintings. The subject of the Nativity is often used for altarpieces, many of these combining both painted and sculptural elements. Other sculptural representations of the Nativity include ivory miniatures, carved stone sarcophagi, architectural features such as capitals and door lintels, and free standing sculptures.

Free-standing sculptures may be grouped into a Nativity scene (crib, creche or presepe) within or outside a church, home, public place or natural setting. The scale of the figures may range from miniature to life-sized. These Nativity scenes probably derived from acted tableau vivants in Rome, although Saint Francis of Assisi gave the tradition a great boost. This tradition continues to this day, with small versions made of porcelain, plaster, plastic or cardboard sold for display in the home. The acted scenes evolved into the Nativity play.

The wider Nativity story in art

[edit]

The scope of the subject matter which relates to the Nativity story begins with the genealogy of Jesus as listed in the Gospels of both Matthew and Luke. This lineage, or family tree is often depicted visually with a Tree of Jesse, springing from the side of Jesse, the father of King David.

The Gospels go on to relate that a virgin, Mary, was betrothed to a man Joseph, but before she became fully his wife, an angel appeared to her, announcing that she would give birth to a baby who would be the Son of God. This incident, referred to as the Annunciation is often depicted in art. Matthew's Gospel relates that an angel dispelled Joseph's distress at discovering Mary's pregnancy, and instructed him to name the child Jesus (meaning "God saves").[1] This scene is depicted only occasionally.

In Luke's Gospel, Joseph and Mary travelled to Bethlehem, the family of Joseph's ancestors, to be listed in a tax census; the Journey to Bethlehem is a very rare subject in the West, but shown in some large Byzantine cycles.[2] While there, Mary gave birth to the infant, in a stable, because there was no room available in the inns. At this time, an angel appeared to shepherds on a hillside, telling them that the "Saviour, Christ the Lord" was born. The shepherds went to the stable and found the baby, wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in the feed trough, or "manger", as the angel had described.

In the liturgical calendar, the Nativity is followed by the Circumcision of Christ on January 1, which is mentioned only in passing in the Gospels,[3] and which is assumed to have taken place according to Jewish law and custom, and the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple (or "Candlemas"), celebrated on February 2, and described by Luke.[4] Both have iconographic traditions, not covered here.

The narrative is taken up in the Gospel of Matthew, and relates that "wise men" from the east saw a star, and followed it, believing it would lead them to a new-born king. On arriving in Jerusalem they proceed to the palace where a king might be found, and enquire from the resident despot, King Herod. Herod is worried about being supplanted, but he sends them out, asking them return when they have found the child. They follow the star to Bethlehem, where they give the child gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. The men are then warned in a dream that Herod wished to kill the child, and so return to their country another way. Although the gospel mentions neither the number nor the status of the wise men, known as "the Magi", tradition has extrapolated that since there were three gifts, there were three wise men, who are generally also given the rank of king, and so they are also called the "Three Kings". It is as kings that they are almost always depicted in art after about 900.[5] There are a number of subjects but the Adoration of the Magi, when they present their gifts, and, in Christian tradition, worship Jesus, has always been much the most popular.

Either the Annunciation to the Shepherds by the angel, or the Adoration of the Shepherds, which shows the shepherds worshipping the infant Christ, have often been combined with the Nativity proper, and the visit of the Magi, since very early times. The former represented the spreading of the message of Christ to the Jewish people, and the latter to the heathen peoples.[6]

-

Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, the Magi presenting their gifts (mosaic detail), late 6th century, wearing Persian dress, and Phrygian cap

-

Sassetta, The Journey of the Magi, c. 1432–1436

-

The Magi before Herod, French 15th-century stained glass

There are also many detailed series of artworks, ranging from stained glass to carved capitals to fresco cycles that depict every aspect of the story, which formed part of both of the two most popular subjects for cycles: the Life of Christ and the Life of the Virgin. It is also one of the Twelve Great Feasts of Eastern Orthodoxy, a popular cycle in Byzantine art.

The story continues with King Herod asking his advisers about ancient prophesies describing the birth of such a child. As a result of their advice, he sends soldiers to kill every boy child under the age of two in the city of Bethlehem. But Joseph has been warned in a dream, and flees to Egypt with Mary and the baby, Jesus. The gruesome scene of the Massacre of the Innocents, as the murder of the babies is generally referred, was particularly depicted by Early Renaissance and Baroque painters. The Flight into Egypt was another popular subject, showing Mary with the baby on a donkey, led by Joseph (borrowing the older iconography of the rare Byzantine Journey to Bethlehem).

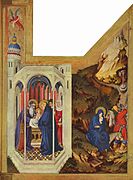

From the 15th century in the Netherlands onwards, it was more usual to show the non-Biblical subject of the Holy Family resting on the journey, the Rest on the Flight to Egypt, often accompanied by angels, and in earlier images sometimes an older boy who may represent, James the Brother of the Lord, interpreted as a son of Joseph, by a previous marriage.[7] The background to these scenes usually (until the Council of Trent tightened up on such additions to scripture) includes a number of apocryphal miracles, and gives an opportunity for the emerging genre of landscape painting. In the Miracle of the Corn the pursuing soldiers interrogate peasants, asking when the Holy Family passed by. The peasants truthfully say it was when they were sowing their wheat seed; however the wheat has miraculously grown to full height. In the Miracle of the Idol a pagan statue falls from its plinth as the infant Jesus passes by, and a spring gushes up from the desert (originally separate, these are often combined). In further, less commonly seen, legends a group of robbers abandon their plan to rob the travellers, and a date palm tree bends down to allow them to pluck the fruit.[8]

Another subject is the meeting of the infant Jesus with his cousin, the infant John the Baptist, who, according to legend was rescued from Bethlehem by the Archangel Uriel before the massacre, and joined the Holy Family in Egypt. This meeting of the two Holy Children was to be painted many artists during the Renaissance period, after being popularized by Leonardo da Vinci and then Raphael.[9]

History of the depiction

[edit]Early Christianity

[edit]

The earliest pictorial representations of Jesus' Nativity come from sarcophagi in Rome and Southern Gaul of around this date.[10] They are later than the first scenes of the Adoration of the Magi, which appears in the catacombs of Rome, where Early Christians buried their dead, often decorating the walls of the underground passages and vaults with paintings. Many of these predate the legalisation of Christian worship by the Emperor Constantine in the early 4th century. Typically the Magi move in step together, holding their gifts in front of them, towards a seated Virgin with Christ on her lap. They closely resemble the motif of tribute-bearers which is common in the art of most Mediterranean and Middle-Eastern cultures, and goes back at least two millennia earlier in the case of Egypt; in contemporary Roman art defeated barbarians carry golden wreaths towards an enthroned Emperor.[11]

The earliest representations of the Nativity itself are very simple, just showing the infant, tightly wrapped, lying near the ground in a trough or wicker basket. The ox and ass are always present, even when Mary or any other human is not. Although they are not mentioned in the Gospel accounts they were regarded as confirmed by scripture from some Old Testament verses, such as Isaiah 1,3:"The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master's crib" and Habakkuk 3,2: "in the midst of the two beasts wilt thou be known", and their presence was never questioned by theologians.[12] They were regarded by Augustine, Ambrose and others as representing the Jewish people, weighed down by the Law (the ox), and the pagan peoples, carrying the sin of idolatry (the ass). Christ was arrived to free both from their burdens. Mary is only shown when the scene is the Adoration of the Magi, but often one of the shepherds, or a prophet with a scroll, is present. From the end of the 5th century (following the Council of Ephesus), Mary becomes a fixture in the scene; then as later Joseph is a more variable element. Where a building is shown, it is usually a tugurium, a simple tiled roof supported by posts.[13]

Byzantine image

[edit]

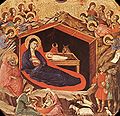

A new form of the image, which from the rare early versions seems to have been formulated in 6th-century Palestine, was to set the essential form of Eastern Orthodox images down to the present day. The setting is now a cave – or rather the specific Cave of the Nativity in Bethlehem, already underneath the Church of the Nativity, and well-established as a place of pilgrimage, with the approval of the Church. Above the opening a mountain, represented in miniature, rises up.[14] Mary now lies recovering on a large stuffed cushion or couch ("kline" in Greek) beside the infant, who is on a raised structure,[15] whilst Joseph rests his head on his hand.[16]

He is often part of a separate scene in the foreground, where Jesus is being bathed by midwives (Jesus is therefore shown twice). Despite the less than ideal conditions, Mary is lying-in, the term for the period of enforced bed rest in the postpartum period after childbirth that was prescribed until modern times. The midwife or midwives come from early apocryphal sources; the main one is usually called Salome, and has her own miracle of the withered hand, although this is rare in art. They featured in most medieval dramas and mystery plays of the Nativity, which often influenced painted depictions. Several apocryphal accounts speak of a great light illuminating the scene, also taken to be the star of the Magi, and this is indicated by a circular disc at the top of the scene, with a band coming straight down from it – both are often dark in colour.[17]

The Magi may be shown approaching at the top left on horseback, wearing strange pillbox-like headgear, and the shepherds at the right of the cave. Angels usually surround the scene if there is room, including the top of the cave; often one is telling the shepherds the good news of Christ's birth. The figure of an old man, often dressed in animal skins, who begins as one of the shepherds in early depictions, but later sometimes addresses Joseph, is usually interpreted as the Prophet Isaiah, or a hermit repeating his prophecy, though in later Orthodox depictions he sometimes came to be regarded as the "Tempter" (the "shepherd-tempter"), an Orthodox term for Satan, who is encouraging Joseph to doubt the Virgin Birth.[18]

The Orthodox icon of the Nativity uses certain imagery parallel to that on the epitaphios (burial shroud of Jesus) and other icons depicting the burial of Jesus on Good Friday. This is done intentionally to illustrate the theological point that the purpose of the Incarnation of Christ was to make possible the Crucifixion and Resurrection. The icon of the Nativity depicts the Christ Child wrapped in swaddling clothes reminiscent of his burial wrappings. The child is often shown lying on a stone, representing the Tomb of Christ, rather than a manger. The Cave of the Nativity is also a reminder of the cave in which Jesus was buried. Some icons of the Nativity show the Virgin Mary kneeling rather than reclining, indicating the tradition that the Theotokos gave birth to Christ without pain (to contradict the perceived heresy in Nestorianism).[19]

Byzantine and Orthodox tradition

[edit]-

Scenes from the life of Jesus Christ, triptych. Constantinople, late 10th century, ivory. Musée du Louvre

-

Andrei Rublev, 1405, in the Moscow Kremlin

-

An Armenian miniature nativity of the savior, 1232

Late Byzantine tradition in Western Europe

[edit]-

Master of Pedret, The Virgin and Child in Majesty and the Adoration of the Magi, Romanesque fresco, Spain, c. 1100

-

Mosaic in Byzantine style, Palermo, 1150

-

Medieval mosaics of Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome, are more classicising in style.

Western image

[edit]

The West adopted many of the Byzantine iconographic elements, but preferred the stable rather than the cave, though Duccio's Byzantine-influenced Maestà version tries to have both. The midwives gradually dropped out from Western depictions, as Latin theologians disapproved of these legends; sometimes the bath remains, either being got ready or with Mary bathing Jesus. The midwives are still seen where Byzantine influence is strong, especially in Italy; as in Giotto, one may hand Jesus over to his mother. During the Gothic period, in the North earlier than in Italy, increasing closeness between mother and child develops, and Mary begins to hold her baby, or he looks over to her. Suckling is very unusual, but is sometimes shown.[20]

The image in later medieval Northern Europe was often influenced by the vision of the Nativity of Saint Bridget of Sweden (1303–1373), a very popular mystic. Shortly before her death, she described a vision of the infant Jesus as lying on the ground, and emitting light himself, and describes the Virgin as blond-haired; many depictions reduced other light sources in the scene to emphasize this effect, and the Nativity remained very commonly treated with chiaroscuro through to the Baroque. Other details such as a single candle "attached to the wall", and the presence of God the Father above, also come from Bridget's vision:

...the virgin knelt down with great veneration in an attitude of prayer, and her back was turned to the manger.... And while she was standing thus in prayer, I saw the child in her womb move and suddenly in a moment she gave birth to her son, from whom radiated such an ineffable light and splendour, that the sun was not comparable to it, nor did the candle that St. Joseph had put there, give any light at all, the divine light totally annihilating the material light of the candle.... I saw the glorious infant lying on the ground naked and shining. His body was pure from any kind of soil and impurity. Then I heard also the singing of the angels, which was of miraculous sweetness and great beauty...[21]

After this the Virgin kneels to pray to her child, to be joined by Saint Joseph, and this (technically known as the "Adoration of Christ" or "of the Child") becomes one of the commonest depictions in the 15th century, largely replacing the reclining Virgin in the West. Versions of this depiction occur as early as 1300, well before Bridget's vision, and have a Franciscan origin.[22]

Saint Joseph, traditionally regarded as an old man, is often shown asleep in Nativities, and became a somewhat comical figure in some depictions, untidily dressed, and unable to help with proceedings. In some depictions, mostly German, he wears a Jewish hat.[23] In medieval mystery plays, he was usually a comic figure, amiable but somewhat incapable, although he is sometimes showing cutting up his hose to make the swaddling-cloth for the child,[24] or lighting a fire.

Saint Joseph's cult was increasingly promoted in the late Middle Ages in the West, by the Franciscans and others. His feast was added to the Roman Breviary in 1479. By the 15th century he is often more dignified, and this improvement continued through the Renaissance and Baroque, until a resurgence of Marian emphasis in the 17th century again often leaves him stranded on the margins of Nativity compositions. The candle lit by Saint Joseph in Bridget's vision becomes an attribute, which he is often shown holding, lit or unlit, in broad daylight.

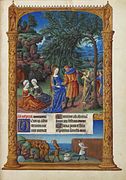

In a fully illuminated Book of hours it was normal to include pages illustrating all four of the Nativity, the Announcement to the Shepherds, the Adoration of the Magi and the Flight into Egypt (and/or the Massacre of the Innocents) as part of the eight images in the sequence of the Hours of the Virgin.[25] Nativity images became increasing popular in panel paintings in the 15th century, although on altarpieces the Holy Family often had to share the picture space with donor portraits. In Early Netherlandish painting the usual simple shed, little changed from Late Antiquity, developed into an elaborate ruined temple, initially Romanesque in style, which represented the dilapidated state of the Old Covenant of the Jewish law. The use of Romanesque architecture to identify Jewish rather than Christian settings is a regular feature of the paintings of Jan van Eyck and his followers.[26] In Italian works the architecture of such temples became classical, reflecting the growing interest in the ancient world.[27] An additional reference made by these temples was to the legend, reported in the popular compilation of the Golden Legend, that on the night of Christ's birth the Basilica of Maxentius in Rome, supposed to house a statue of Romulus, had partly tumbled to the ground, leaving the impressive ruins that survive today.[28]

Ruin symbolism

[edit]The ruin symbolism in "Nativity" and "Adoration of the Magi" paintings first emerged in Early Netherlandish art around the mid-fifteenth century, in a distinct Romanesque style.[29] Early Netherlandish painters began to associate this style with the architecture of the Holy Land, in contrast to the vague Orientalism of earlier depictions. In this context, the Romanesque buildings represented the foreign, old era of Jewish, and/or pagan world, opposite to the native Gothic style of the period. This contrast between two chronological periods – Gothic and Romanesque – replaced the earlier contrast between geographical spheres – Western and Oriental. The main message of the ruin in these paintings is that ancient buildings had to become ruined in order for Christianity to triumph.[30]

Indeed, the inclusion of the ruin was perfectly suitable for the "Nativity" and "Adoration of the Magi" imagery. The birth of Christ represented in the Nativity stands for the birth of Christianity, a new era, which came with the 'ruination' of the old eras of Judaism and paganism. Following this, the "Adoration of the Magi" stands for the spread and acceptance of Christianity all over the world, with each of the three kings representing one of the three continents known at the time. Therefore, the ruined buildings symbolize the 'downfall of disbelief and the salvation of the faithful through Christ's founding of his church.'[31]

However, the Nativity and the birth of Christ does not mean the complete rejection of the old. Even though Jewish people do not recognize Christ as their Savior, Christianity believes that the Israelites prophesied the coming of Christ all throughout the Old Testament. This paradox remained unresolved during the Middle Ages, during which the relation between Judaism and Christianity was a very ambivalent one. This ambivalence was solved by Early Netherlandish artists, who began using the Romanesque style and then the ruin symbolism, which express a continuation between the Old and the New Testament. Ultimately, the birth of Christ under a Romanesque ruin conveys harmony and the reconciliation of the present with the past.[32] In this way, the Nativity symbols the 'juncture between the era of prophecy and that of fulfilment.'[33]

The ruin symbolism in "Nativity" and "Adoration of the Magi" paintings was soon adopted by artists of the Italian Renaissance, who began painting ruins of classical buildings rather than Romanesque ones. The same idea of continuity between the Old and the New Testament is present in the works of Italian artists as well, but here there is an additional complicating factor: the Renaissance humanist ideal. Artists were supposed to depict Christianity's triumph over paganism, i.e. the antique world, despite the fact that they were living during the time of antique revival. Therefore, even though the buildings depicted by Italian artists were ruinous in state, they still retained the 'full grandeur of classical content.'[34] The aim of Renaissance artists was to rethink the post-medieval relationship between antiquity and Christianity.[35] For Italian artists of the period, therefore, the Nativity and thus the birth of Christ came to be merged with the 'period's own conception of itself as one of rebirth.'[36] The "Nativity" and "Adoration of the Magi" imagery during the Italian Renaissance was a testament to historical consciousness, in which ruins served as documents of the glorious pagan past waiting to be studied and emulated.[37]

Medieval

[edit]Early Medieval Western images

[edit]-

The earliest Western Madonna and Child, from the Book of Kells, at the beginning of the Gospel of Matthew. c. 800

-

Nativity and Annunciation to the Shepherds from the Bamberg Apocalypse 1000–20, Ottonian

-

Romanesque capital from Saint-Pierre, Chauvigny, 12th century

-

German illuminated manuscript with two scenes of the Magi, c. 1220

-

Depicted in an early English Missal c. 1310–1320

Gothic

[edit]-

12th-century glass from Basilica of Saint Denis, Paris, with a proper bed for Mary

-

13th-century French glass at Canterbury Cathedral with the full story of the Magi and typologically related scenes

-

English alabaster with Mary in a bed, attended by a midwife

-

14th-century French ivory triptych showing the Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity with, unusually, Joseph holding the baby, while Mary sleeps; Presentation and Magi.

International Gothic

[edit]-

Presentation at the Temple and Flight, with legends of the idol and spring, Melchior Broederlam, Burgundy, c. 1400

-

The miracles of the palm tree and corn on the Flight into Egypt, from a book of hours, c. 1400

-

In this 1403 panel by Conrad von Soest Saint Joseph cooks a meal as Mary cares for Jesus.

-

A greater degree of sentimental elaboration is in this German miniature of 1420

Proto-Renaissance in Italy

[edit]-

Pulpit Relief from the Pisa Baptistry by Nicola Pisano, 1260, is based in style on the reliefs of Roman sarcophagi.

-

The Nativity in the Scrovegni Chapel by Giotto is very close in composition and style to the sculpture at Pisa.

-

Bernardo Daddi was influenced towards realism by the paintings of Giotto.

-

Taddeo Gaddi painted the first large night scene in this Annunciation to the Shepherds.

Renaissance and after

[edit]From the 15th century onwards, the Adoration of the Magi increasingly became a more common depiction than the Nativity proper, partly as the subject lent itself to many pictorial details and rich colouration, and partly as paintings became larger, with more space for the more crowded subject. The scene is increasingly conflated with the Adoration of the Shepherds from the late Middle Ages onwards, though they have been shown combined on occasions since Late Antiquity. In the West the Magi developed large exotically dressed retinues, which sometimes threaten to take over the composition by the time of the Renaissance; there is undoubtedly a loss of concentration on the religious meaning of the scenes in some examples, especially in 15th-century Florence, where large secular paintings were still a considerable novelty. The large and famous wall-painting of the Procession of the Magi in the Magi Chapel of the Palazzo Medici there, painted by Benozzo Gozzoli in 1459–1461 and full of portraits of the family, only reveals its religious subject by its location in a chapel, and its declared title. There are virtually no indications that this is the subject contained in the work itself, although the altarpiece for the chapel was the Adoration in the Forest by Filippo Lippi (now Berlin).

From the 16th century plain Nativities with just the Holy Family, become a clear minority, though Caravaggio led a return to a more realistic treatment of the Adoration of the Shepherds. The compositions, as with most religious scenes, becomes more varied as artistic originality becomes more highly regarded than iconographic tradition; the works illustrated by Gerard van Honthorst, Georges de La Tour, and Charles Le Brun of the Adoration of the Shepherds all show different poses and actions by Mary, none quite the same as the traditional ones. The subject becomes surprisingly uncommon in the artistic mainstream after the 18th century, even given the general decline in religious painting. William Blake's illustrations of On the Morning of Christ's Nativity are a typically esoteric treatment in watercolour. Edward Burne-Jones, working with Morris & Co., produced major works on the theme, with a set of stained glass windows at Trinity Church, Boston (1882), a tapestry of the Adoration of the Magi (ten copies, from 1890) and a painting of the same subject (1887). Popular religious depictions have continued to flourish, despite the competition from secular Christmas imagery.

Early Renaissance

[edit]-

Piero della Francesca (unfinished)

-

Domenico Ghirlandaio, with classical ruins

-

Botticelli; his patrons, the Medici family, are depicted as the Magi and their retinue.

High Renaissance

[edit]-

This terracotta relief by Giovanni della Robbia shows the Christ Child as part of the Holy Trinity, adored by Mary, Joseph and Franciscan saints.

-

This complex Adoration of the Magi by Leonardo da Vinci was never completed.

-

The Doni Tondo represents the Holy Family resting on the way to Egypt; Michelangelo.

-

The meeting of the Infant Christ and John the Baptist was a popular subject of Raphael.

Renaissance in Northern Italy

[edit]-

Adoration of the Shepherds, Mantegna

-

Giorgione, Nativity, c. 1507

-

Lorenzo Lotto, 1523

Northern Renaissance

[edit]-

Ellhofen Altarpiece, Germany, following Saint Bridget's vision

-

Bartholomäus Bruyn Altarpiece, Saint Johann Baptist Essen

-

Joachim Patinir, Flight into Egypt. At right the miracle of the corn, at top left the falling idol

Mannerism

[edit]-

Adoration of the Shepherds, Bronzino

-

Dirck Barendsz, 1565, Janskerk (Gouda)

-

Jacopo Bassano, The Adoration of the Magi

Baroque and Rococo

[edit]-

El Greco, Baroque Adoration of the Shepherds lit by the Christ Child

-

Adoration of the Magi, Rubens, 1634

-

Gerard van Honthorst Adoration of the Shepherds, still influenced by Saint Bridget

-

Adoration of the Shepherds, Charles Le Brun

After 1800

[edit]-

Romantic Rest on the Flight by Philipp Otto Runge, 1806

-

Flight by Carl Spitzweg, 1875-9

-

British Orientalist artist Edwin Long, Anno Domini, 1883, shows the arrival in Egypt

-

Late 19th-century stained glass of The Adoration of the Shepherds and the Magi, Cologne Cathedral

-

Nativity by Gustave Doré 1891

-

The Journey of the Magi by James Tissot, 1894. Like most of his Biblical illustrations, treated largely as Orientalism

-

Paul Gauguin, 1896, with a Tahitan setting

-

Adolf Hölzel, 1912

Popular art

[edit]-

Folk painting, 17th century, by Mikael Toppelius

-

Presepe by Francesco Landonio around 1750

-

Bible illustration c. 1900

-

A Nativity Creche made by Bill Egan of Florida, 21st century

See also

[edit]- Nativity of Jesus in later culture for interpretations in other forms of art (music, opera, novels, etc.)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Matthew:1:21. The name Jesus is the Biblical Greek form of the Hebrew name Joshua meaning "God, our salvation".

- ^ Schiller:58

- ^ Luke 2:21

- ^ The dates vary slightly between churches and calendars – see the respective articles. In particular, the Eastern Orthodox churches celebrate the visit of the Magi, as well as the Nativity, on December 25 of their liturgical calendar, which is January 7 of the usual Gregorian calendar.

- ^ Schiller:105

- ^ Schiller:60

- ^ The subject only emerges in the second half of the 14th century. Schiller:124. In some Orthodox traditions the older boy is the one who protects Joseph from the "shepherd-tempter" in the main Nativity scene.

- ^ Schiller:117–123. The date palm incident is also in the Quran. There are two different falling statue legends, one related to the arrival of the family at the Egyptian city of Sotina, and the other usually shown in open country. Sometimes both are shown.

- ^ See, for example, Leonardo's Virgin of the Rocks

- ^ Schiller:59

- ^ Schiller:100

- ^ Schiller:60. In fact this sense of the Habakkuk is found in the Hebrew and Greek Bibles, but Jerome's Latin Vulgate, followed by the Authorised Version, translates differently:"O Lord, revive thy work in the midst of the years, in the midst of the years make known" in the AV

- ^ Schiller:59–62

- ^ The mountain follows Scriptural verses such as Habakkuk 3.3 "God [came] from Mount Paran", and the title of Mary as "Holy mountain". Schiller:63

- ^ partly reflecting the arrangement in the Church of the Nativity, where pilgrims already peered under an altar into the actual cave (now the altar is much higher). The actual altar is sometimes shown. Schiller:63

- ^ Schiller:62-3

- ^ Schiller:62–63

- ^ Schiller:66. In late works a young man may fend the tempter off. See: Léonid Ouspensky, The Meaning of Icons, p. 160, 1982, St Vladimir's Seminary, ISBN 0-913836-99-0. In pp.157–160 there is a full account of the later Orthodox iconography of the Nativity.

- ^ Ouspensky, Leonid; Lossky, Vladimir (1999), The Meaning of Icons (5th ed.), Crestwood NY: Saint Vladimir's Seminary Press, p. 159, ISBN 0-913836-99-0

- ^ Schiller:74

- ^ Quoted Schiller:78

- ^ Schiller:76-8

- ^ For example Schiller, figs. 173 & 175, both from Lower Saxony between 1170 and 1235, & fig. 183, 14th century German.

- ^ from about 1400; apparently this detail comes from popular songs. Schiller:80

- ^ Harthan, John, The Book of Hours, p.28, 1977, Thomas Y Crowell Company, New York, ISBN 0-690-01654-9

- ^ Schiller, pp. 49–50. Purtle, Carol J, Van Eyck's Washington 'Annunciation': narrative time and metaphoric tradition, p.4 and notes 9–14, Art Bulletin, March 1999. Page references are to online version. online text. Also see The Iconography of the Temple in Northern Renaissance Art by Yona Pinson Archived March 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schiller:91-82

- ^ Lloyd, Christopher, The Queen's Pictures, Royal Collectors through the centuries, p.226, National Gallery Publications, 1991, ISBN 0-947645-89-6. In fact the Basilica was built in the 4th century. Some later painters used the remains as a basis for their depictions.

- ^ Panofsky, Erwin (1971). Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character. The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, 1947–1948. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 131–141.

- ^ Hui, Andrew (2015). "The Birth of Ruins in Quattrocento Adoration Paintings". I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance. 18 (2): 319–48. doi:10.1086/683137. S2CID 194161866.

- ^ Hatfield, Rab (1976). Botticelli's Uffizi "Adoration": A Study in Pictorial Content. Princeton Essays on the Arts, 2. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press. p. 33.

- ^ Panofsky, Early Netherlandish Painting: Its Origins and Character, pp. 137–139.

- ^ Gerbron, Cyril (2016). "Christ Is a Stone: On Filippo Lippi's Adoration of the Child in Spoleto". I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance. 19 (2): 257–83. doi:10.1086/688500. S2CID 192182697.

- ^ Hatfield, Botticelli's Uffizi "Adoration": A Study in Pictorial Content, p. 65.

- ^ Hui, "The Birth of Ruins in Quattrocento Adoration Paintings," 348.

- ^ Hui, "The Birth of Ruins in Quattrocento Adoration Paintings," 323.

- ^ Zucker, Paul (1961). "Ruins. An Aesthetic Hybrid". The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 20 (2): 119–130. doi:10.2307/427461. ISSN 0021-8529. JSTOR 427461.

References

[edit]G Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I,1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, pp. 58–124 & figs 140–338, ISBN 0-85331-270-2